We are from that Land: Transversal Dialogues between Art and Territory.

Mélanie Mozzer and Savio Ribeiro

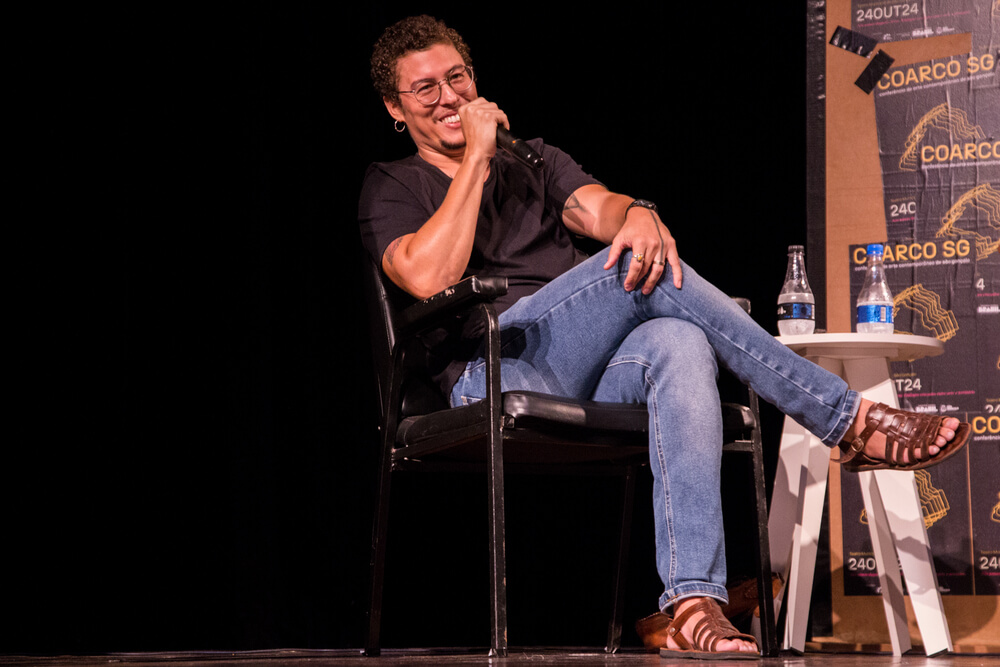

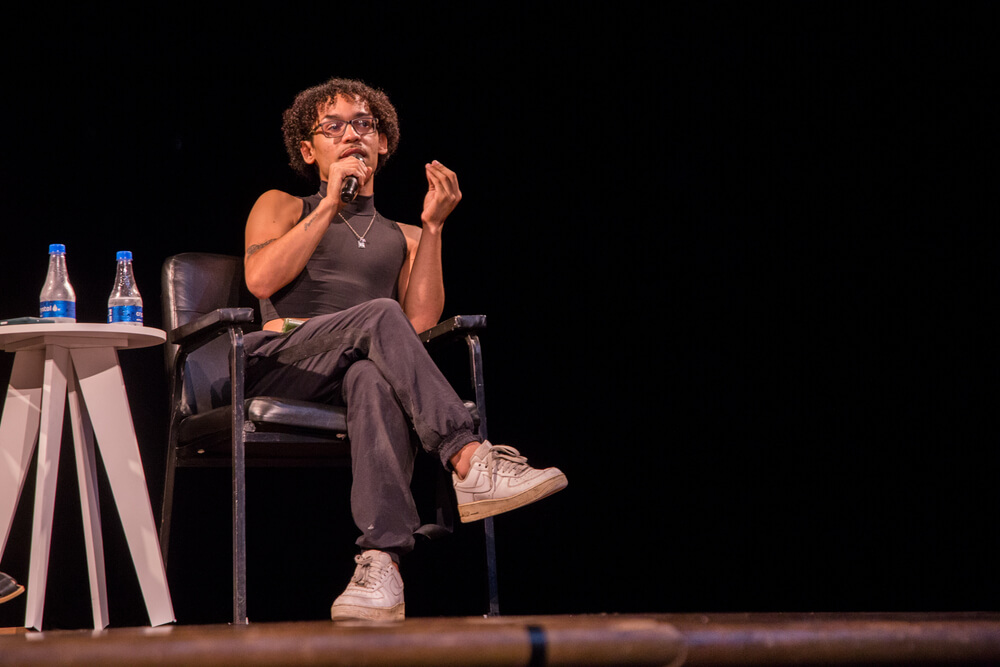

In 2024 we had the great pleasure of organizing the first edition of Coarco (Contemporary Art Conference of São Gonçalo) with the theme “We are from that Land: Transversal Dialogues between Art and Territory” featuring presentations by nine special guests who brought their perspectives and experiences in the intersecting areas of art, education, and culture.

The conference was born out of a commitment to fostering formative dialogue in the city and region of São Gonçalo: bringing together artists, producers, educators, cultural agents, and the local public in a space for listening, exchange, and reflection on contemporary art. São Gonçalo is the second-largest municipality in the state of Rio de Janeiro, second only to the capital. Located across Guanabara Bay, on the outskirts of the so-called “marvelous city,” it bears the challenges and stigmas common to suburban cities, marked by historical neglect by public authorities and urban violence. Even so, São Gonçalo is fertile territory: it shelters, trains, and exports countless artists, strengthening cultural and creative networks that endure and reinvent themselves despite adversity.

In recent years artists, educators and activists from the region have been demanding a more just and dignified artistic existence, seeking a relationship that transcends the old peripheral dynamic in relation to the metropolitan center. We want our city to be not only the birthplace of artists, but to become a space that shelters art in all its forms: a bed, a home, a stage, a school, and, above all, a land that respects and values its voices.

Our goal is to foster collective growth through debate that strengthens local cultural networks and inspires new paths for the development of the arts. In this conversation, we reflect on the event, its history, the artists and issues involved, and its relationship to the theme of this issue of Revista MESA, “Body, Ground, Heart.” We invite readers to immerse themselves in this meeting of ideas and experiences.

Savio Ribeiro: My name is Savio Ribeiro, I am one of the founders of Defluxo, a contemporary art platform focused on artistic and pedagogic investigations, and together with Mélanie Mozzer, co-curator of the São Gonçalo Contemporary Arts Conference (Coarco). I am an artist, educator, performer, and currently a master’s student in the Graduate Program in Contemporary Arts Studies (PPGCA) at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF).

Mélanie Mozzer: I’m Mélanie Mozzer, an art educator, curator, and cultural producer. I have an undergraduate arts degree from the Fluminense Federal University. I’m also the founder of the Defluxo Platform and co-curator of Coarco. I’m also currently a member of the education team at the Moreira Salles Institute. I think that’s it.

Savio: I keep wondering why this Coarco conference became so interesting to us? The proposal, above all, began as an exercise in discussing art within a territorial context. This becomes necessary when we realize the urgency of competing for institutional spaces and producing collectivity around and reflecting on contemporary peripheral artistic knowledge. For me, it begins to make sense within this impulse. To speak out, to bring dialogue almost as an entity to act within a territory that is often stereotyped as peripheral, marginalized, or alien from the perspectives of those in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Mélanie: For me, the conference was also a very symbolic discussion. We’re talking about an entire day dedicated to art inside the São Gonçalo Municipal Theater, in the city center. It’s about affirming this territory as a space for dialogue.

Coarco also emerged from our experiences as cultural producers in this region. This daily pendular migration in search of knowledge or artistic work outside the territory equally drives us to create initiatives and educational opportunities here. We want artists from São Gonçalo to be able to travel to Rio not out of necessity, but by choice. It’s a fight to establish spaces that offer cultural projects in the municipality.

Even with limited publicity and on a day of heavy rain, the theater drew a significant audience. This confirms what we’ve already observed: there are many artists and people interested in art in the city, but who still need to leave to produce and pursue their education. The audience demonstrated this potential, and this also connects to the theme we chose to inaugurate the first edition and which drove the discussions throughout the day. Savio, maybe you can talk a little about the choice of this theme and the title “We are from that Land: Transversal Dialogues between Art and Territory”?

Savio: Yes, of course. So, at the time I was reading [Afro-Brazilian author and activist] Nêgo Bispo. I had been deeply impacted by his thinking and writing and as we were reflecting on the title of this edition, this sentence in particular struck me: “We arrive as inhabitants, in any environment, and we gradually transform ourselves into sharers. […] We are only residents when we do not have a relationship of belonging.”1 So, for individuals who are peripheral or directly related to these peripheries, the territory needs to be experienced and performed differently. For us, it was urgent to act against the subjugating logic, for example, of the dormitory city.

“We are from that Land” emerged from Bispo’s provocation about the relationship between housing and belonging. For us, this phrase carries a double meaning: on the one hand, it expresses the subject’s deep connection to the “Land,” a land constantly being cemented and rejected in the name of urban development; on the other, it conveys the common experience of many artists from São Gonçalo, who experience this municipal exodus, only finding their peers, artists and art thinkers, outside the city limits. In this dislocation, “from that” gains strength as the expression of someone distant, but who affirms their belonging. “We are,” even in absence, keeps in our hearts an identity tied to territory. Thus, “We are from that Land: Transversal dialogues between art and territory” became a title capable of condensing the images and desires that move us: making the conference a space to discuss art in São Gonçalo.

Mélanie: You raised a lot of what informed our choice of theme. We couldn’t begin a conversation about art without firmly planting our feet in this territory. São Gonçalo was our non-negotiable starting point. We also chose the artists and panel participants from this perspective. We wanted voices that know in their bodies this pendular movement: leaving their margins toward the so-called “center.” But what center is this? These artists, as they experience this daily migration, when they reach this supposed center, don’t present themselves merely as ceramists, sculptors, curators, or performers. Before any title, they affirm: “I’m from São Gonçalo,” “I’m a product of the ZO [slang for São Paulo],” or “I’m from Caxias.” In this gesture, there’s not just naming: there’s belonging. The territory, then, is not just a background: it’s a living ground, a present body, an axis that sustains and convokes. Each dialogue drew on this.

Savio: Well said Melanie!

Another fundamental step in building the first Coarco was curating each of the roundtables, right? How do these agents – artists, educators, curators, writers etc – connect with their territories? What kind of encounters did we want to foster during this day of conversations? Is our goal for this program to engage in conversations in São Gonçalo, only with people from São Gonçalo, for a São Gonçalo audience?

From questions like these, we realized that the conversation about “periphery” is also a conversation about the so-called “center” and the conversation about the “margins” is also a conversation about the “middle.” Here, we were interested in expanding the notion of peripheries, understanding not only the places surrounding the center, but also how this connection to the center can be strategic. Thus, bringing together São Gonçalo, Brás de Pina, Duque de Caxias, and Aracaju [all municipalities and suburban regions surrounding the city of Rio de Janeiro] – connections that would once have been unlikely – became essential to the composition of our discussions.

Melanie: Another key gesture in curating these panels was bringing artists, professors, and curators from the national scene to São Gonçalo. While we were actively cultivating dialogues with some local names, such as Gabriella Marinho, Gabi Bandeira, or Jefferson Medeiros, the presence of others, such as Guilherme Vergara, a professor at the Fluminense Federal University, or Antonio Amador, an artist who had been part of the 2023 São Paulo Biennial, also carries symbolic weight. This movement inverts the usual logic. This shift is a political gesture. It strains the notion of center and reorients our gaze to São Gonçalo, not as a periphery, but as a meeting ground. What emerged there was not just proximity, but connection.

Savio: This proposal to reorient São Gonçalo as a meeting place reminded me that, on the day of the conference, there were many people in the audience who weren’t from the city. In a way, we managed to establish another movement: a flow from the capital to the periphery. This intersection, in fact, is one of the foundations of the artistic-pedagogical platform we created, right, Mélanie? To give our readers a little more context, the Defluxo Platform is an exercise in creating spaces between flows—or in creating opposing flows within the discourses and contexts of contemporary art. Anyone who wants to learn more can find our Instagram page under the same name. But, returning to the curation of the panels and participants, I think we can now talk about the themes that sparked each roundtable. What do you think, Mélanie?

Mélanie: I think we can start with the first panel, which was called “Art Education: The Role of the Artist in the Construction of the Peripheral Imagination.” Here a panel focusing on art education kicked off the event. Art critic and professor João Ovídio made a point during this panel that made a lot of sense to me when he said that he doesn’t believe in artistic or cultural production that doesn’t consider education. So, starting this conference with the theme of education was very important. In addition to João Paulo Ovídio, who is from Caxias, we also had Ivan de Oliveira and Jefferson Medeiros, both artists and educators from São Gonçalo.

Savio: Yes, the first presentation of the first panel of the first São Gonçalo art conference was given by Ivan de Oliveira. Ivan has been an artist and actor for a long time, and he’s also a public-school educator in the municipality of São Gonçalo. I met Ivan de Oliveira through encouraging and supporting Fernando Mattos’s work at Colégio Walter Orlandini, where theater workshops were held for interested students. Ivan is, not only a living master, he is also a reference for deeply rooted artistic work. Besides the impact of his work in theater, Ivan’s practice resonates in the imagination of young people trying to figure out where they can step. He begins his presentation by saying:

I’m part of the Complexo do Salgueiro community, here it’s only the police force that is present. And when we bring students into this transformative moment through art, they discover opportunities beyond the one they’re currently experiencing. That’s my role.

So, thinking about the theme of this panel, Ivan acts as a key engine for the peripheral imaginary, precisely by establishing modes of permanence in the artistic and artistic-pedagogical field.

Melanie: There’s also something precious about Ivan having taught so many artists. He embodies the potential of the public-school educator, who, in the everyday classroom, opens up worlds of possibility. When I started university in the undergraduate art program, I didn’t believe it was feasible to make a living from art. Imagine, then, a child in elementary school. And yet, how many students became artists because of an encounter with Ivan? He acted as a mirror.

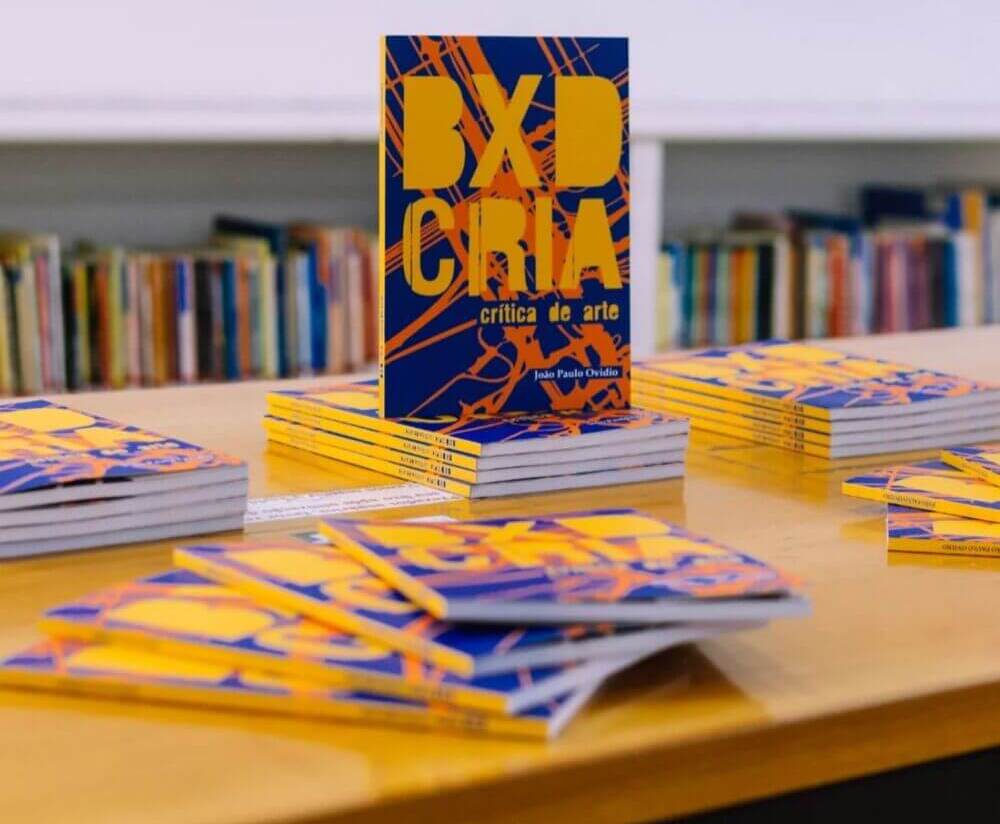

This was also why it made sense to me to bring João Paulo Ovídio into the dialogue. He himself states:

This year I have completed ten years of work in the field of art education, and my first experience was in my own territory, which isn’t a reality for everyone.

His journey in Baixada is a gesture of self-reference: by publishing his book, he writes his own story and inscribes his territory into art historical narratives.

I see, in the curatorial and pedagogical work that Ovídio has done, a way of expressing himself in the world, you know? At Education Faculty of Baixada Fluminense, in Duque de Caxias, Ovídio reinvents the curriculum. In his classes, he uses artistic references from the Baixada, so he brings the university to the margins, reordering the traditional places of discourse and knowledge. That’s why we invited him to São Gonçalo: to consider how we can also articulate our own references.

The contribution that Jefferson Medeiros brought to this panel was also very important to me. Peripheral bodies are key to his work where he constructs autonomous narratives and contributes to the disruption of colonial ideals. How he connects with São Gonçalo impresses me, especially when he states:

My artwork originates from São Gonçalo. It’s from this city that I construct my worldview, my perspective on the world.

He says that his work is a tool that projects new horizons and that’s why we can no longer allow our story to be told by other people.

This moment of dialogue at the conference was very important where the discussion was opened up amongst the panelists together with the audience. This stimulated very important reflections and questions such as: How do we create these new horizons? How do we establish and follow the telling of our stories? How do we present this work as a scream?

Savio: In the second panel, “Pendular Body: The Performativity of Everyday Life and the Journey of the Periphery,” we sought to reflect on how artists and agents think about the workday and other daily journeys. Here, performativity is understood not only as artistic expression, but also as the expression of the body situated within the demands and tensions of the periphery.

With Gabriella Marinho, Alan Adi, and Antonio Amador present, we began the conversation by asking our guests whether it would be possible for a peripheral body to produce from “creative idleness.” At first glance, it might seem like a casual provocation, but I believe we fostered deep exchanges about the creative bodies of peripheral workers. I remember Alan reflecting on the image of the artist-worker, a notion that permeates his research as he challenges the stereotypes associated with Brazil’s Northeast and their permanence in the national imagination. Alan investigates the social legacy of these images, and in videos, photographs, and installations, connects them to central issues in Brazilian society, such as migration, economics, history, and education. Something that particularly resonated with me was his reflection on the artist-worker:

We’re workers, right? So, what’s a worker’s body like? It’s hard-edged. It’s tired. This image of the gifted artist, who just waits for inspiration… doesn’t exist. […] We’re shoemakers, seamstresses, tailors, cooks… we’re workers. In that sense, we share the same afflictions. No one here is elite.

Gabriella Marinho’s presentation also drew our attention to the fact that this pendular movement is not only about moving between places of work or study, but also the task of balancing desires.

I was born and still live in Jardim Catarina, where I grew up. And when I introduce myself, I talk about the people who raised me: my mother, my grandmother, and my aunt—these three women who were always on the move. They always tried to combine formal work, their craft, with creative processes.

This is something that’s always happened, ever since I can remember. I think part of my heritage came from this path: understanding work processes and being able to combine these formal processes with the creative ones, which shape me as a person.

This panel raised the following questions: how can we produce using methodologies of reinvention, dissident methodologies, or even methodologies that recreate the limits already inscribed in peripheral bodies?

Along these lines Antonio Amador’s reflections are really to the point. Antonio’s performance work explores the body and its transdisciplinary intersections. Together with Jandir Jr., he developed the art duo Amador & Jr. Segurança Patrimonial Ltda., where dressed as security guards they develop performance proposals in art institutions. The work stems from the tensions between these institutions and the workers who work daily to safeguard them. This tension also exists with people working as educators and mediators, a context in which Amador is familiar in his work at various institutions. In the following talk, he reflects on how one of these experiences exemplifies his thinking about creative leisure:

See, this relationship of creative leisure is very much limited to a certain type of social class that organizes it in this condition. A person who isn’t necessarily concerned, for example, with paying the bills, experiences a different structure, a different sociability. I like to use examples from my own life. In 2014 or 2015, I worked at the Caixa Cultural in Rio de Janeiro as an exhibition monitor. Back then, there were no benches to sit on: we stood the entire time, we couldn’t sit down. It was always this dynamic, monitoring the people who walked by. Caixa was right there on Carioca Avenue, and lots of people passed by. But there were times when the gallery was empty, and we had to remain standing, waiting for the end of the day. Often, we’d already seen the exhibition several times. So, in trying to devise strategies to pass the time, I started using the program flyers: I’d stand at the door, handing them out and making up things to start conversations.

For example: there was a photojournalism exhibition, and I’d hand out a flyer saying, “Hi, how’s it going? You can take photos of reality here.” Many people just took it and walked in, paying no attention. But some were interested, and then we’d start a conversation about what a mediation like this in a gallery could entail. This is an example of how leisure, in this context, was not free time for poetic creation, but a strategy for mental comfort amidst physical fatigue and waiting. I think there are two ways to understand this: on the one hand, the modern idea of “creative leisure,” linked to a privileged artist; on the other, what we create as strategies to resist oppression, suffering, and day-to-day and work-related fatigue.

Mélanie: This panel discussion was truly invaluable. As part of this exercise of revisiting what was discussed, a talk by artist Gabriella Marinho deeply resonated with me. She spoke about the experience of identifying with and being mobile through her work with clay. Discussing creative leisure, she explained that she creates and works in the same space where she lives: Jardim Catarina, in São Gonçalo.

When asked if it’s possible to find creative leisure in an exhausted body, Gabriella responded that, at home, anxiety consumes her. Her path is to reconnect with her surroundings: she goes out, walks around the neighborhood, observes the ground, the clay, and in this reconnection finds the energy to return to work. From this, she defines how she views her relationship with her work:

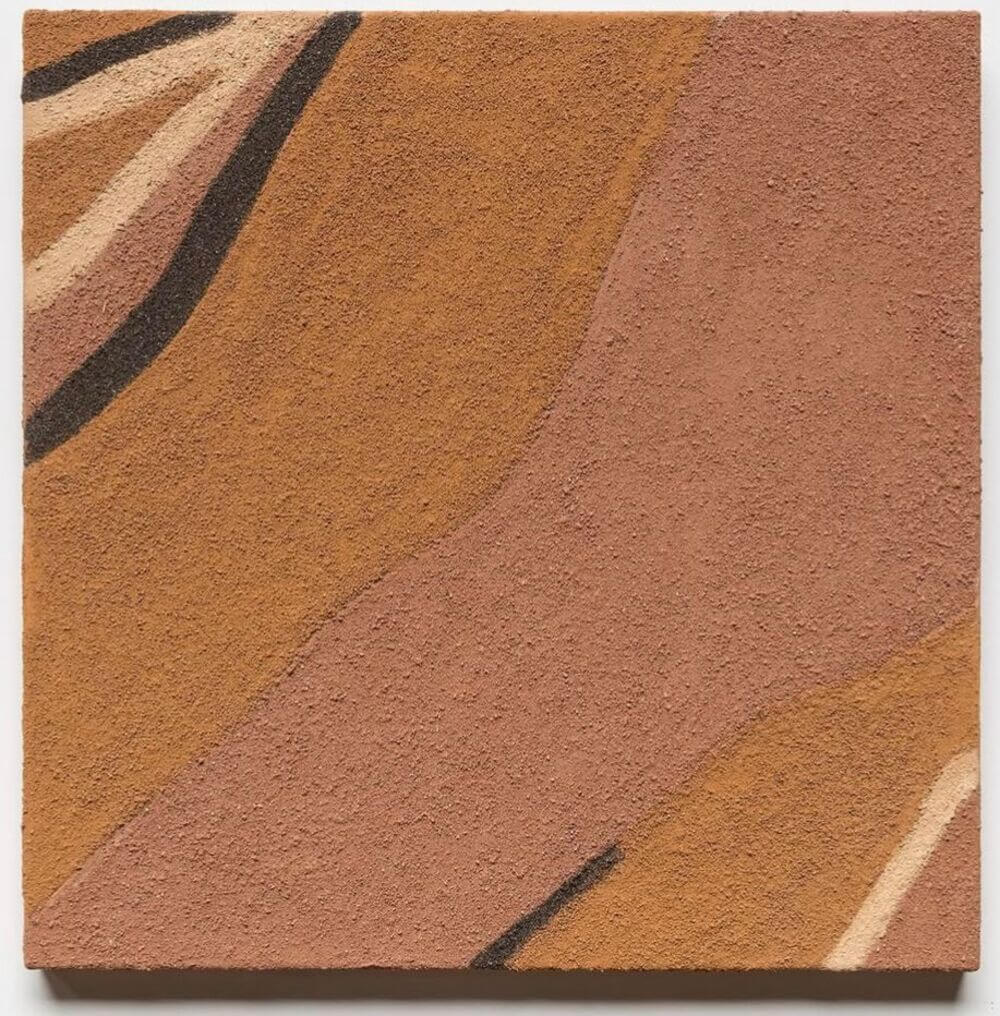

So, I think and try to see myself through the material I use. It’s not just a material that defines the language of my work, but also the way I place myself in the world.

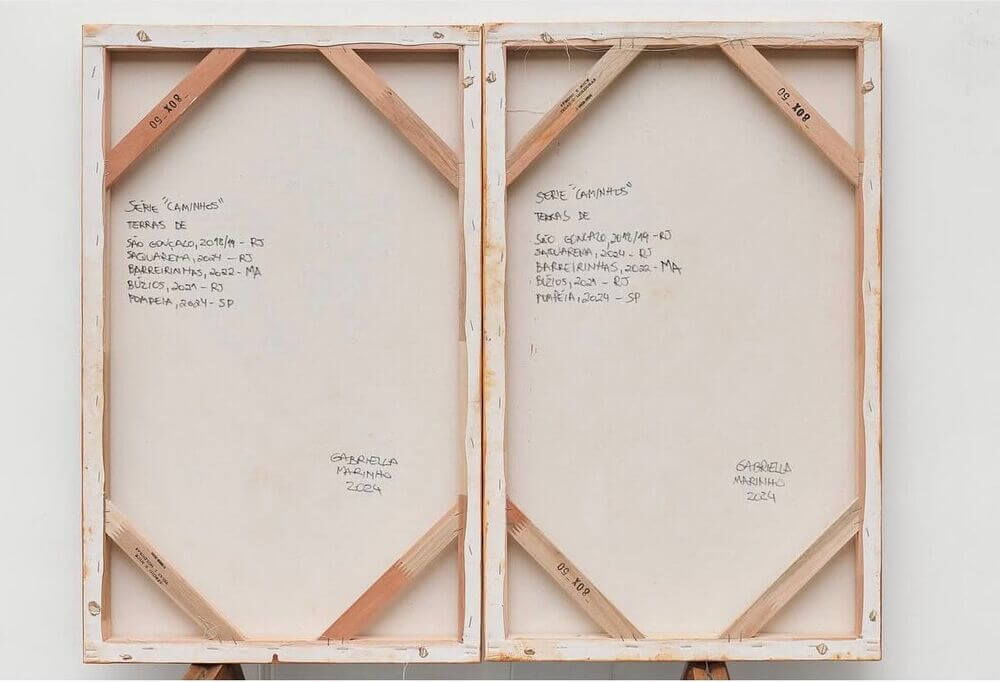

It’s beautiful how she builds this relationship with the territory, the place where she comes from, where she works, where she has grown up, where she shares connections with people. More than that, she uses this soil, this clay, as material to develop her artistic production. For those unfamiliar, Gabriella works with clay from Jardim Catarina, but also from the places where she travels. If she’s in São Paulo, she collects clay from there. If she’s in Rio, she uses Rio clay. In residences abroad, she brings clay from these other places. Thus, her work also becomes a kind of transit between body, ground, and heart.

a) Notes behind the screen of dates and locations of lands collected from 2018 to 2024

b) Series Caminhos, 2024

Savio: This connection between Marinho’s work and what we’re trying to think about in this issue of Revista MESA is very interesting! Now it’s going to be hard to separate Gabriella’s practice from these themes. If only all problems were as beautiful as this, right?

But, yes, let’s move on to the third and final dialogue “Fictionalizing Futures: Insurgent Practices from the Peripheries.” Here, we begin with the understanding that being able to imagine is a condition of empowerment. It is necessary to fictionalize a better future for a possible future to exist. Almost like an exercise in sustaining perspectives. However, in a colonized environment, subjects are deprived of this ability: they are not allowed to fantasize, their imaginations are not nurtured or cultivated.

We understand that the city is a territory marked by collective experiences. So, we’re interested in exploring whether it is possible to intertwine artistic relationships in such a way that these territorial boundaries are altered, thus changing symbiotic relationships and shared experiences. It’s not just about working or producing, but also about inhabiting the realm of ideas. Sometimes, even about inhabiting rest, in order to then inhabit thought. It was within this horizon that we welcomed Gabriela Bandeira, Guilherme Vergara, and Rothyer Kali.

Mélanie: One of the most interesting things about this conversation was your question about how these artists’ works can serve as a kind of ground to think about the future, for fictionalizing these futures. I remember Rothyer, when introducing herself, saying she was a pioneer of ballroom culture in São Gonçalo. Ballroom culture is an artistic, social, and political movement created by Black and Latinx LGBTQIAPN+ people, which emerged in the United States in the 1970s as a response to exclusion and as a form of resistance, acceptance, and identity affirmation. Being a pioneer in this context seems doubly potent, being the first person to practice and articulate ballroom culture in a given territory. To achieve this, she conducted research on ballroom culture in Rio de Janeiro and throughout Brazil.

In her talk, she highlighted how ballroom culture can be a home for people who are socially excluded for various reasons. A home in the sense of shelter, respite, care, and a place for the possibility of existence. After all, how can we think about the future if the basics of existence are not guaranteed? From this perspective, ballroom is, above all, about having a house, a home, a place to exist, and then to be able to create and pursue artistic goals.

In this same conversation, Gabriela Bandeira talks about how we’ve become disenchanted with our bodies. Gabi runs a social art program called aGradim, where she brings together collective efforts to examine urban mutations and ecosystems to mobilize new practices that disrupt the environment and provide new ways of seeing everyday life. This project takes place at Praia das Pedrinhas, in São Gonçalo, home to a large community of regional fishermen. For Gabi, the city needs to be reenchanted again, and we, as artists, are also at the service of finding ways to both create and repeat narratives of enchantment. She adds:

In early October, I revisited an old experience. When I was a child, I used to frequent Praia da Luz, Itaoca, and Itaúna. But as security in the city changed, it became increasingly difficult to enter these areas, not only for fishermen but for the entire population of São Gonçalo.

But I was able to develop a project there, serving 19 young people from a school, CIEP Carlos Marighella, in Itaoca. I was invited through the Mangue Doce [Sweet Mangroves] project, which aims to create environmental education practices linked to the honey being produced in the mangroves. Of the 19 young people that participated, 16 were children of artisanal fishermen. And they all knew the names of the species that lived in that mangrove. This is science and knowledge.

What strikes me as truly powerful in the work of Rothyer and Gabriela, is that it’s not just about seeking knowledge outside of the region, but about returning and giving back. The return becomes even more important than the departure.

Savio: Mélanie, what a luxury it is to be contemporaries Rothyer and Gabi. It is beautiful to share time with people whom we deeply admire. We can perceive in these agents (curators, artists, educators, researchers, or producers) a way of thinking that goes beyond rational logic.

If it were purely logical, there would be no reason for them to return to their communities, which often lack references, support, or opportunities. But they return because they also think with other bodies, with other organisms—a visceral and disobedient way of thinking.

Mélanie: I agree, Savio. I think that throughout the history of art, constructing narratives from the perspective of the other has become naturalized—the other who begins to write, interpret, and criticize what emerges from within our territories. This logic silences us because it fails to record our own creations, where we can narrate our own revolutions.

It’s crucial to refocus on our territory. As Gabi Bandeira said, “If we’re always focused on the center (the center of Rio, which is also the center of disputes), we’ll always be behind.” But if we focus our attention, our bodies, on our soil, our territory, on what we’re producing, thinking, and articulating, the logic reverses, because we’ll be producing from where we are.

Finally, it’s crucial to emphasize: there are people producing knowledge in this territory. There are people creating the future in this place.

Savio: To conclude our reflections on the first Contemporary Art Conference in São Gonçalo, I thought to wrap up with an excerpt from the last panel from our professor and friend Luiz Guilherme Vergara.

I think it’s very important that we don’t transform the term “dreaming” into an alienation from reality. Artists are agents of a “diurnal dreaming” because they work—and working is also dreaming. It’s not an alienating dream, an escape from reality. It’s an active dream proving itself through experience. That’s what we’re here for. Art comes in a way that’s often not immediate. But it touches the essence of what it means to be alive. Because, yes, you can postpone your dreams, your talents, you can buy consumer compensations. But when we have people like these artists here, they are sparks— it is not about escaping.

I’m here in São Gonçalo because I believe in the importance of all São Gonçalo communities. I’ve met with students from São Gonçalo at the Federal Fluminense University (UFF) several times. Their engagement brings a vitality that’s very different from that of a comfortable, middle-class person. This resilience is a fundamental factor in artistic transformations. This is what I call utopian pragmatism: thinking about reality, but not settling for the reality that is given now. And I say this also recognizing what Gabi said: this whole sphere of parallel powers that runs through the Baixada: fires, threatening of indigenous territories; violence… There is a whole universe of alert, of disenchantment. But then the question arises: how do we use this adversity to understand a vital need for art?

So, this concludes our conversation on the first edition of the São Gonçalo Contemporary Art Conference, which now reverberates in the “Body, Ground, Heart”edition of MESA magazine. For those who want to delve deeper, see the links to the full panel discussions below, along with our Instagram contacts.

We are Mélanie Mozzer and Savio Ribeiro, and we want to deeply thank Revista MESA for the invitation and also Luiz Guilherme Vergara and Jessica Gogan, for their collaboration in this process.

We continue together, producing, thinking, and dreaming futures from the perspective of this ground. Thank you very much!

Link to access the full video of the panels: São Gonçalo Contemporary Arts Conference – YouTube

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/plataforma.defluxo/

***

Mélanie Mozzer

Mélanie Mozzer is an art educator and curator, a native of São Gonçalo, a territory that permeates and teaches her daily. With a Bachelor of Arts from the Fluminense Federal University, she works across cultural production, curation, and education, always based on attentive listening and a countercolonial perspective. She created and directs the Defluxo Platform, a space for creation and research in visual arts and education. Her practice seeks to challenge modes of knowledge production, creating spaces for listening, presence, and exchange, where dissident bodies can imagine together.

Savio Ribeiro

Savio Ribeiro is a master’s student in the Graduate Program in Contemporary Arts Studies (PPGCA) at Fluminense Federal University (UFF), and holds an undergraduate arts degree from the same institution (2024) with the research project Bege Não É Cor de Pele (Beige Is Not Skin Color) dedicated to the investigation of color, representation, and raciality. He works in performance, critical pedagogies, and dissident performing practices. He is a co-founder of the Defluxo Platform, an artistic-pedagogical space for collaborative curation and performative investigations, where he develops research and practices focused on the creation and critique of the arts. He is also a member of the UFF Arts Center team, collaborating on the staging of exhibitions and the dialogue between artists, curators, and institutions.

1 Nêgo Bispo, a terra dá, a terra quer (São Paulo: Ubu Editora, 2023) 38.