Crouch Designing

Ana Luiza Nobre

The farmer or engineer who cuts into the land can either cultivate it or devastate it.1

Robert Smithson

A tired man bends down to take off his shoes and unexpectedly encounters the memory and pain of his grandmother’s death. The Proustian image is the starting point for philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman’s reflection on “thinking while leaning over,”2 a mental activity connected to a kind of tactile knowledge derived from a movement toward a relational closeness to things. Not in the Benjaminian sense of proximity as immersion, associated with the modern world and its technologies of mechanical reproduction and affected by a kind of distracted (provided by cinema) and no longer attentive perception (along the lines of painterly traditions). For Didi-Huberman, the elimination of the receding point of view does not mean the loss of critical distance, as in Benjamin, but the possibility of accessing deep dimensions of the mind from a bodily experience in which the distance of vision is replaced by the intimacy of touch. “Lean over to see and think better,” he writes, as if the mere bending of the body towards the ground offered the possibility of displacing thought –a way of looking at the world – insofar as it detaches one from a point of view fixed in a dominant and hierarchically superior position, with its pretensions to totality and stability.

As opposed to the “master-of-all perspective” of a subject removed from the world and positioned on an elevated plane, what Didi-Huberman calls an “embracing vision” would rather imply a corporeal wisdom; a sensitive and mundane body, which, by bending over itself and abandoning, even for a moment, the independence and loftiness associated with an upright posture, would make “what is below rise up to us”. Here, the humble and trivial gesture of bending towards the ground is interpreted as an event: the opening up to a kind of knowledge that emerges from unexpected affections and unforeseen encounters between different temporal, spatial, perceptual, and existential modulations and inversely to the pure and immaculate knowledge of the master-of-all perspective.

Letting what’s below “come up to us, towards our gaze and thought.” If taken in architectural terms, the problem posed by the French philosopher points to the possibility of thinking about the indissoluble relationship between architecture and the ground together with a set of ethical, theoretical and political questions that have been sharpened as a result of the radical nature of the urban and political environmental crisis we are currently experiencing; a crisis that simultaneously demands a reorientation of our everyday goals and practices, the expansion of our sensitive capacities, and the deconfinement of our planetary, design and urban imagination.

After all, as Didi-Huberman reminds us, aerial vision has not only been used for surveillance, domination and/or bombardment. The very scope of the project was fundamentally defined in architecture from the perspective of the Albertian winged eye, emblem of the Renaissance universal man. Just think of the plan for Sforzinda, the ideal city conceived by Filarete in the 15th century. Or, later on, Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse (1924-35). And of course, it is also the exaggerated and disembodied aerial perspective that guarantees the success of GoogleMaps and GoogleEarth, digital visualization tools of the planet that have been freely available on the web since the beginning of this century and are now used indiscriminately by architecture students and professionals as if they were faithfully mirroring (and even replacing) an unsuspected reality in which projects will be installed, and perhaps materialize.

In contrast, “thinking while leaning over” would correspond to a re-encounter of the architectural project with a tangible dimension of the world, as a result of abandoning a top-down view and an objectifiable spatial orientation, anchored in forms of scientific knowledge and measurable coordinates (by means of geographical and/or geometrical systems), and replacing it with the vacillating horizon of a body leaning over. A re-encounter that can also be understood, in Bruno Latour’s terms, as a sort of “landing.” In other words, as a movement that is configured as a counterpoint to the processes of modernization/globalization established in opposition to everything that is local, rooted, and linked to a ground/soil. A move that cultivates a politics of the Terrestrial, motivated by the desire to regenerate a common plane ruined by the destructive logic of petrocapitalism – largely anchored in architecture– and involves answering with whom we want to be, share, live and connect with in this vertiginous moment in which “the ground collapses under everyone’s feet at the same time.”3

This idea can be extended to those who crouch down or squat. Those who crouch down see/think differently. And it is in the crouching/squatting position that many traditional cultures find comfort, enjoyment, and carry out daily and ceremonial tasks. For many indigenous peoples, it is in a squatting position that women prepare food, build fires, mold and shape pottery, bear children and even sweep.4 It is also from a squat that men watch for game, attend meetings, practice shamanism, rest and wait for fights such as huka-huka to begin.5 Squatting prompts bone remodeling, reorganizes the body, and places it in a different psychic-sensory-motor relationship with everything around it. Everything is experienced at a slower pace, in a more organic way, without the imperatives of vertical force or the haste of the upright body, in a more earthy relationship with life. In play and in pain.6

There is a lot to learn from this body that refuses the haughtiness of an upright posture and surrenders to gravity. Even in architectural terms. The question would be how to think/design while leaning/crouching/squatting? A position that involves considering the impact that architectural, urban and landscape projects have or can have on the quality of the ground, as well as aligning with anti-colonial perspectives that fight for the historical reparation of silenced peoples subjected to compulsory displacement, forced removals, and dispersal. A way of working that operates through critical approaches and procedures that fight for the re-signification of the ground as a policy of reterritorialization and re-appropriation of lands that were converted into property, wealth and sovereignty and to make a case for their restitution to the bodies forcibly removed from them by colonial violence. [Such ways of working] seek to reverse a history of radical expropriation whose biopolitical and necropolitical effects took on very tangible contours in Brazil with Jair Bolsonaro government’s (2019-2022) open policy of extermination, including a scheme to divert Covid vaccines intended for indigenous peoples to gold miners in exchange for gold, as one terrible example.7 In this context, looking at the ground means, above all, reaffirming the memorial and indexical dimension of the ground as a way of resisting a systematic policy of erasure. It means searching for traces of ancestral settlements abased by state violence and extractivist logics, mapping them, making them visible, and referring to them as a legal basis in lawsuits, demanding the recognition of lands plundered through pillage and human rights violations, as Paulo Tavares does.8

Here, leaning over and crouching down can be a movement of reparation. Reparation, that is, understood in relation to three distinct meanings [in Portuguese of reparar]: as noticing, detecting, recognizing marks and references; as retracting, compensating, mitigating or settling injustices committed against communities or social groups; and as being attentive, caring.

At the same time, squatting can be understood as “designing with your feet on the ground.” In other words, designing while being more fully aware of the present moment and in balance with the earthly energy emanating from the center of the Earth. Designing barefoot, as someone who is at ease walking on the beaten earth and who identifies with what is stripped of possessions and ornaments (a meaning that is at the origin of the expression “ground architecture,” coined by the American historian George Kubler to refer to the sobriety that characterizes a group of works – mostly vernacular – built in Portugal between the 16th and 17th centuries, in contrast to the ornamental excesses of Manueline architecture).

Designing while leaning over, designing while crouching, with your feet on the ground, barefoot – what is being proposed, in any case, is a way of thinking-doing architecture that means caring for the ground, being attentive to the infinite possibilities of connection that are rooted in it and spring from it. Let’s think of the ancestral image of bare feet kneading the earth to produce bricks. What could be closer to an “all embracing vision” in architecture than such a way of thinking-doing that is ethically and politically committed to that which, par excellence, communes us? That is to say, the plane in which we are all, human and non-human, implicated, a threatened dimension yet one that is full of concrete, affective, historical, symbolic, and cultural meanings, indispensable to the very sense of human orientation, and on which the habitability of planet Earth depends. A vision that, at the same time, is committed to the creation of a common world, one that is heterogeneous and non-totalizing (in other words, always open to arrangements and rearrangements, compositions and recompositions)?

Of course, one does not have to dig through the history of architecture to find projects and works that show a strong relationship with the ground, on different scales and in different geopolitical and historical-cultural contexts. This could include, for example, the Villa Adriana in Tivoli and the Tidal Pool in Leça da Palmeira by Álvaro Siza; the Basilica of San Clemente in Rome and the French Communist Party Headquarters in Paris by Oscar Niemeyer; the Robin Hood Gardens by Alison and Peter Smithson in London, or the Lugar de la Memoria (Place of Memory) by Barclay & Crousse in Lima, Peru. As well as countless vernacular works, such as the adobe skyscrapers in Shibam, Yemen, and the indigenous malocas built on rammed earth in the Amazon region. From the point of view of the relationship with the ground, these works show a plurality of approaches that can be seen in Siza’s “gripping lines,”9 the Smithsons’ ground notations10 and the materiality of the buildings in Shibam. Each one in its own way, however, is defined by procedures that are quite different from the elevation of the building by means of pilotis and are averse to some of the founding themes of modern architecture, namely universalism, the tabula rasa and the autonomous object, to be read gesturally as a figure on an indistinct background. But how can architecture – historically obsessed with heights and devoted to human and urban exceptionalism – make the ground come up to us? To what extent can getting closer to the ground help open up new architectural approaches at a time when the habitability of the planet is under threat, and architecture itself is in a deep and unprecedented crisis? What architectural-urban-landscape projects, thinking and practices can help regenerate, strengthen and even fertilize the ground, and thus also help us overcome an overpowering, anthropocentric vision of architecture that is proving to be increasingly unsustainable?

It’s certainly not just about installing “green roofs” on buildings, energy efficiency systems, water reuse or accessibility for people with special needs – all of which are used as bargaining chips in the rich global market to earn “sustainability labels.” Just take Santiago Calatrava’s project for the Museu do Amanhã [Museum of Tomorrow, Rio de Janeiro). While celebrated as the first Brazilian museum to obtain the gold LEED certification (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, one of the most vaunted sustainable construction labels in the world), the building’s costly concrete media-appealing structure is installed over the polluted waters of Guanabara Bay – a UN World Heritage Site and a postcard of Rio de Janeiro, whose depollution, touted as one of the main Olympic goals for the 2016 games, has never been fulfilled.11

Nor is it enough to lift the building off the ground, as the Andrade Morettin Studio did for the new campus of the Institute of Pure and Applied Mathematics (IMPA) in Rio de Janeiro, which extends almost 10,000 square meters over what little remains of the Atlantic Forest.12 Even though this same project was highlighted for its supposed “minimal impact”13 in one of the most competitive international awards for sustainable construction (the Lafarge Holcim Awards, created significantly by one of the world’s largest cement manufacturers. In other words, by an industry that heads one of the most environmentally damaging production cycles and today is estimated to be directly or indirectly responsible for emitting half of all the CO2 generated by human activities on the planet14).

Undoubtedly, there are other design parameters guiding the type of approach addressed here, whose basic condition is the “stepping softly” of those who move gently, and above all carefully, on the planet. Those that walk mindfully and attentively to the impact of their own footprints, guided not by the impetus of domination but by the intention of building/rebuilding/expanding territories, symbiotic communities, and relationships of affinity and solidarity. Design-wise, this is one of the great challenges facing architecture today, one that may translate into different operational strategies and involve the most varied techniques, but is certainly not restricted to the prerequisites fostered by the opportunism of so-called “green buildings,” nor can it be measured numerically according to the competitive logic of ranking sustainability certifications and seals. It’s better to think of projects that are sensitive to the touch between the building and the ground, and to the specific conditions of the environment in which they are located. For example projects: that demonstrate topographical thinking, avoiding massive earth movements and changes in the water table; that are concerned with building landscapes and territories, not objects and images; that oppose waterproofing and extensive paving, guaranteeing the soil’s permeability and porosity; that combat desertification, contamination and soil mortification by creating spaces that are free and open to transformation; that value elevation management and ground-floor design, on the scale of the foot; that impose limits on design, considering waiting as a possibility and not doing as an eco-political strategy; that go against the logic of ownership and enclosure, seeking to foster practices that establish the commons and commit to replacing fossil fuels with alternative energy sources; that favor local and reusable materials and ensure waste reduction; and that rely on production systems based on social equity and the preservation of the ecosystem, in its multiple components (socio-cultural, economic, technical and ecological).

In short, we could say, projects that care for the ground – even assuming the imprecision and plurality of meanings that the term brings together. That associate advanced technology with bare feet and not with high-tech rhetoric. 15Ones that operate through situated, entangled, terrestrial practices. Or, following Luiz Rufino’s point, projects that try to vibrate with the tone of the ground.16 In other words, that recognize, listen to, and dignify the ground as a primordial dimension of existence where multiple beings, bodies, forces, writings, lexicons, logics, and powers intersect. Grounds that are also an expression of the violent relations of the black African diaspora and of ancestral knowledge that continues to circumvent the homogenizing regime of colonialism.

Ways of leaning/squatting

Curiously, even though architecture is a decisive agent in both the construction and destruction of the ground, the architectural field still seems little mobilized beyond a set of projects and reflections on this topic that have basically been configured around a few key axes within which I will distinguish three practices (not opposing but in various ways distinct): the Lefebvrian vindication of the right to the city, which tends to associate the ground floor with public space (res-publica); the revalorization of the platform as a physical-archetypal support with a political dimension, whose elevated top redefines social-spatial relations, according to the genealogy outlined by Jfrn Utzon; and the revision of the concept of landscape, which emphasizes geomorphological forms resulting from the surface manipulation and exploitation of the ground (largely guaranteed by the use of digital techniques).

Identified with the liberation of the ground floor, the first of these axes has Lina Bo Bardi’s MASP/Museu de Arte de São Paulo (1961-68) as an emblematic landmark from both a technical-architectural and political-symbolic perspective.17 The second is identified with the network of playgrounds implemented by Aldo van Eyck in Amsterdam (1947-78) and, more recently, with projects such as Robson Square in Vancouver (Arthur Erickson and Cornelia Oberlander, 1984), in which different uses and relationships are organized and activated through a system of steps and level differences.18 Another example of this second practice which stands out in recent years is Foreign Office Architects’ Yokohama International Port (1995-2002) – and before it, we could say, Paulo Mendes da Rocha’s Pavilhão do Brasil in Osaka (1970). These projects tend towards the creation of artificial topographies and geomorphic architectures, with increasing computer support in the modeling of complex topological surfaces that dissolve the distinction between figure and background and the objectual character that characterizes much of modern architecture.19

The formulation outlined here indicates, however, that there are many other ways of designing with the relationship between architecture and the ground in mind that we may be even less aware of, and in which a kind of squatting is recognized. A good example is the “chula” (stoves) designed by Yasmeen Lari allowing Pakistani women to cook squatting in open air, in accordance with their ancestral traditions, but installed on an earth-platform, and therefore in more hygienic and safer conditions of food preparation, avoiding a series of illnesses resulting from the contamination through direct contact with ground dirt. Lari’s project has led to the creation of thousands of earthen structures across Pakistan, using natural fuels (organic waste, twigs or sawdust), built and decorated by the very women who use them, after receiving training in centuries-old construction techniques. The same architect has also worked on several other initiatives that combine care for the ground with environmental concern, low cost, and community engagement in critical situations, within what she calls “Barefoot Social Architecture” (BASA). It’s quite significant, by the way, how this involves a self-criticism of her own trajectory, marked by large-scale, for-profit building projects using industrial, high-polluting, and often imported materials, until a devastating earthquake radically transformed her approach to architecture: “I discovered that walking without shoes helps us to live lightly on the planet and to use the Earth’s resources judiciously”, says Lari.20

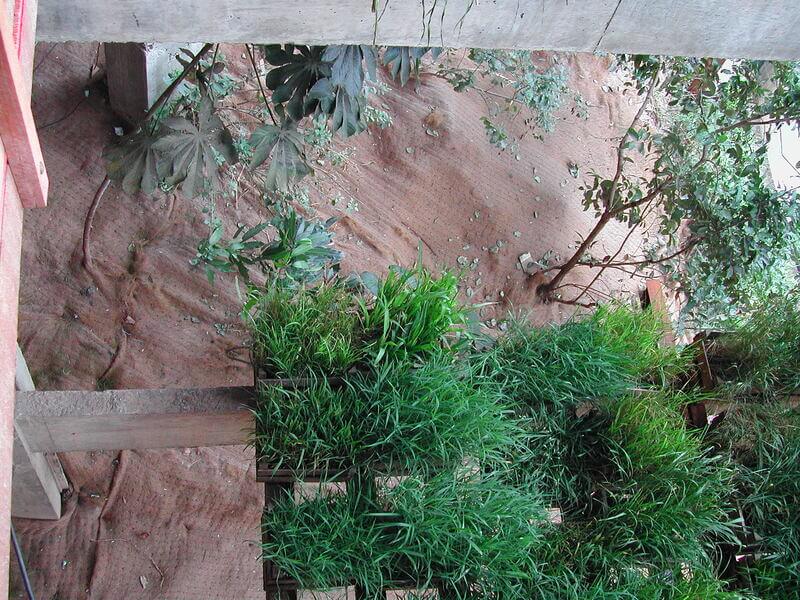

The Minas Gerais based Vazio Studio with their “concrete stilts” created for the Buritis neighborhood in Belo Horizonte offers another example. A residual structure resulting from the schizophrenic disconnection between architecture and topography that characterizes an entire neighborhood built by the real estate market in the 1990s was converted into collectively appropriable space via an ephemeral architecture. Basically, it was a question of activating the ground by inserting, between the concrete pillars and beams under the buildings, a Piranesian path of walkways, ramps, and stairs, associated with a landscape project of environmental recovery through the arrangement of wooden boxes with grass and the covering of the hillside with coconut fiber mesh, in a gigantic blanket from which life began to sprout.

Another example to point out is Carla Juaçaba’s Humanity Pavilion for Rio + 20 [United Nations conference on sustainability held in 2012, marking twenty years after the first earth summit in Rio de Janeiro, 1992]. While similar to architectural lifting operations, this project is nevertheless unique in how it “steps on the ground” in such a radical way. The pavilion featured 7,000 supports using a pre-existing structure that left the ground intact, even though weighing 500 tons, including an auditorium for 500 people and welcoming more than 100,000 people in its two-week duration. In this way, the Pavilion performs a kind of suspension, less like MASP and more like the sentry architecture of the MST/Landless Rural Workers Movement: no foundations, no earthworks, and ready to go at any time. And through a relationship with the ground that is not one of force or domination, but of reciprocity. A reciprocity intrinsic to touch, of the mutual action between the toucher and the touched.

These are architectures that in some way respond to Ailton Krenak’s call to “step softly on the ground,”21 and perhaps point to the possibility of thinking about a gaiarchitecture, i.e. a geopolitically orientated architecture that is concerned about its impact on the planet (its “footprint”) without falling for the rhetoric of sustainability and greencapitalism. An architecture that counteracts the order of the “expansive paving over” of the planet and the uprooting of modernization/globalization processes with projects that are linked to the ground and seek to cultivate/activate/fertilize/strengthen/regenerate it.

We find this kind of thinking-doing-leaning-crouching also in the work carried out by indigenous artist and activist Denilson Baniwa at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo22 – one of the leading museums in Brazil, designed by the internationally celebrated architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha. Baniwa’s work consisted of planting a small garden of flowers, medicinal herbs and pepper plants in the gaps between the stones that pave the Pinacoteca’s main access and car park, and was maintained for a few weeks thanks to a network of people who took turns, voluntarily, to water and take care of the plants. The sowing was carried out at the height of the pandemic, exactly two years after the fire at the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro consumed a collection comprising pieces from hundreds of indigenous peoples. This opened up a critical dialogue between worlds: the invisible, metaphysical world of the Baniwa peoples and the concrete, visible world of the city; the indigenous world and that of non-indigenous institutions; the ephemerality of the garden and the architectural claim to eternity.

The work has thus challenged the state institutions that define, by exclusion, what art, culture and heritage are. At the same time, it called into question a strongly authorial and canonical architecture, as if reversing the Faustian pact with a modernizing project that led the Goethian character to violently dig up the ground in his eagerness to build more and more buildings and cities. What remains of this garden is an architectural lesson: the advanced technology here is certainly not that of the free span, concrete, steel, and human exceptionalism, but that of the bare foot and the crouching body. That’s enough to remind us how our smallest gestures can be decisive for the construction, destruction or regeneration of the ground.

“Design Crouching” was originally published in Sentidos de chão edited by Ana Luiza Nobre and Caio Calafate (Rio de Janeiro: Rio Books, 2022). Revised and translated for this publication.

***

Ana Luiza Nobre is an architect, historian and professor in the Department of Architecture and Urbanism at PUC– Rio and coauthor of Atlas do Chão (Ground Atlas) atlasdochao.org)

1 Robert Smithson, “Frederick Law Olmstead and the dialectical landscape” in: Flam, Jack, ed. Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996) pp. 157-171, p. 164.

2 Georges Didi-Huberman, Pensar debruçado (Lisbon: KKYM,2015).

3 Bruno Latour, Onde aterrar? Como se orientar politicamente no Anthropocene (Rio de Janeiro, Bazar do Tempo, 2020) p. 17.

4 As shown in the film As mulheres das cócoras made in the Assuriní village of Xingu, by Graziela Rodrigues and Regina P. Müller. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SinFo62gNDE (Accessed 12/10/21).

5 Marilia Carvalho de Mello Alvim and Dorath Pinto Uchôa, “Efeitos do hábito de cócoras no tálus e na tíbia de indígenas pré-históricos e de um grupo atual do Brasil” in: Rev. do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, S. Paulo, 3: 35-53, 1993.https://www.revistas.usp.br/revmae/article/view/109159(Accessed12/10/21)

6 See, on the one hand, the beautiful study of children’s toys and games with earth and soil by Gandhy Piorski (Gandy Piorski, Brinquedos do chão: a natureza, o imaginário e o brincar (São Paulo: Peirópolis, 2016)). And on the other, the funeral ceremony conducted by Davi Kopenawa and other Yanomami shamans in 2015, in which more than 2,000 blood samples collected without consent in the 1960s by researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and used in North American laboratories for genetic research, were opened one by one and poured into a hole in the ground: https://www.survivalbrasil.org/ultimas-noticias/10739 (Accessed 12/10/21)

7 As found by the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry/CPI on Covid, set up in April 2021. See “Documento na CPI da Covid aponta troca de vacinas contra Covid por ouro em terras indígenas”. Folha de S. Paulo. 07/06/21.https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2021/06/documento-na-cpi-da-covid-aponta-troca-de-vacinas-por-ouro-em-terras-indigenas.shtml. Accessed on 09/06/21

8 See in particular the expropriation of the Xavante people’s land by the Brazilian military government in the 1960s in order to promote a model of economic development committed to large-scale farming and infrastructure projects. In: Paulo Tavares, Memória da Terra (Brasília: Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, 2020).

9 An expression used by the architect Álvaro Siza in reference to his design process for the Piscina das Marésin the documentary Álvaro Siza, Obras e Projetos directed by Luís Ferreira Alves and Vítor Bilhete, 2001.

10 For an in-depth study of the Smithsons’ rooting strategies as opposed to the objectual character predominant in modernist architecture, see Casino, David. “Tactics of configuring the floor plan: Alison &Peter Smithson”, in Nobre, Ana Luiza and Calafate, Caio. Sentidos do chão. Rio de Janeiro: Comum, 2022. p.91-108 (Disponível em: atlasdochao.org/matéria) Acesso em 23/04/2025

11 It is estimated that Guanabara Bay receives 18,000 liters of untreated sewage per second and 90 tons of rubbish a day. Its depollution, promised as one of the main Olympic legacies, was decisive in Rio de Janeiro’s bid to host the Games, after the failure of successive programs aimed at its socio-environmental recovery. The promise was not fulfilled, however, and during the Rio 2016 Games only palliative measures were adopted, such as eco-barriers installed at the mouths of rivers. See Emanuel Alencar, Guanabara Bay: Descaso e resistência (Rio de Janeiro: Mórula, 2016).

12 According to data from the SOS Mata Atlantica Foundation, the area covered by the forest is now equivalent to 12.4% of its original vegetation, with deforestation having more than doubled in Rio de Janeiro and Mato Grosso do Sul and exceeded 400% in São Paulo and Espírito Santo between 2019 and 2020. See Atlas da Mata Atlantica: http://mapas.sosma.org.br/ (Accessed 17/10/2021)

13 See https://www.lafargeholcim.com.br/onde-operamos The impact was questioned by environmental organizations and provocated a petition signed by 2387 people as of 17/10/2021. See: /ministerio_publico_prefeitura_do_rio_de_janeiro_im_nao_ao_impa_na_barao/. (Acessed 17/10/2021)

14 Cf Wellington Cançado,”Civil deconstruction” in: Piseagrama 10. p.106

15 Cf pointed out by Renata Marquez in Gabriel Teixeira Ramos’ doctoral thesis, “Maps-movements: narratives of urban displacement through (other) workings of cartographic systems, Institute of Architecture and Urbanism-USP, 25 June, 2021.

16 An expression used by Luiz Rufino when talking about crossroads in the Cycle of Meetings “Sentidos do chão”, DAU/PUC-Rio, May 6th 2021.

17 See Ana Luiza Nobre, “Ground as Project” in: Andres Lepik and Daniel Talesnik. Access for all. São Paulo’s architectural infrastructures (Park Books, 2019) p.90-93.

18 See Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara, “Platforms: Architecture and the use of ground” in: https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/conditions/287876/platforms-architecture-and-the-use-of-the-ground/e lecture by Pier Vittorio Aureli on the subject at the Federal Polytechnic School of Lausanne on 16.09.2020:https://planlibre.ch/platforms-architecture-and-the-use-of-the-ground-pier-vittorio-aureli-16-09- 2020/(Accessed 17/10/2021)

19 See Stan Allen and Marc Maquade eds., Landform Building. Architecture’s New Terrain (Baden: Lars Müller Publishers, 2011). Dominique Perrault, Groundscapes. Other topographies (Orleans: Hyx, 2016) and the special edition of the magazine Quaderns 220, “Del Suelo” with texts by Alejandro Zaera-Polo,Manuel Gausa and others

20 Talk by Yasmeen Lariat TED x Talk on 15/10/2020: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NAWdvYgHMXs. See also 100 Day Studio, organized by The Architecture Foundation on 06/08/21: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0JZKiJQais0 (Accessed 12/10/2021)

21 “O tempo para respeitar a Terra acabou:” Ailton Krenak Interview with Keila Bis, on 15/04/2020. https://yam.com.vc/sabedoria/775794/ailton-krenak-o-tempo-para-respeitar-a-terra-acabou (Accessed on 06/09/21).

22 Hilo”, part of the work entitled “Nada do que é dourado permanence” was realised in the context of the group exhibition “Véxoa: nós sabemos,” presented at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, curated by Naine Terena, between October 2020 and March 2021.

![Thaís.Aquino_foto.livro.apoio_2]](https://institutomesa.org/revistamesa/edicoes/7/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2025/09/Thais.Aquino_foto.livro_.apoio_2.jpg)