Body, Gesture, Affect: A Project with Women from Talavera Bruce Prison

Alice Poppe, Caroline Valansi, Tania Rivera and Tato Taborda

The following is an edited transcript of a dialogue held on August 29, 2024 that brought together artists and researchers originally planned as separate roundtables: “Sharing Gestures: Corporal Experiences with Women Deprived of Liberty” an ongoing project with women from Talavera Bruce prison and “Audionutrition: Sound Objects, Alterities and Sharing Listening” on practices of radical listening. These roundtables were proposed as part of a series of dialogues coordinated by Professor Luiz Guilherme Vergara (UFF/PPGCA) for the 6th International Meeting of RACS “Múltiplas Vozes em Defesa das Vidas, Saúde Única, Arte Plural e Formação Humana” (Multiple Voices in the Defense of Lives, One Health, Plural Art and Human Education).

Tania Rivera: I am delighted to be here today and to have this discussion with such great and dear collaborators: Alice and Caroline, who make up the team of the project “Body, Gesture, Affect: A Project with Women from Talavera Bruce Penitentiary,” and Tato Taborda, a dear colleague who I always love to listen to. I would like to propose that Maria Alice Poppe and Caroline Valansi briefly introduce themselves and then Tato speaks first about what he calls audionutrition, after which we can then connect this to our experience in the prison. It’s funny, things really go by resonances, which is an important word for Tato too. In fact, the title of his very wonderful book, which I recommend, is Ressonancias: vibrações por simpatia e frequências de insurgência (Resonances: Sympathetic vibrations and insurgent frequencies).

By way of a curious resonance, Alice and I had actually thought about starting our discussion here with something to do with listening, as a way to introduce our project, that in addition to Alice and Carol in 2023, included the participation of Natasha Pasquini and Beatriz Veneu and in 2024, Taianne de Oliveira. Our proposal is very experimental and is not based on a theory or indeed any already established practice. It is, for us, more about instituting a practice than reworking an already established one. Alice and I began without having a theory or an established program to support us, neither in practical, nor poetic terms. Perhaps this is, precisely, the core of the proposal, understood as an attitude or a clinical-political stance. The public moment of multiple and shared listening that this round table offers us today is very important for us, so that we can try to understand, in a plural way, what we are doing. I said that the project would have to do with listening because, in a conversation with Alice about another project, I came up with the idea of talking about the notion of choreolistening, as a way to think about such corporal proposals, in which movements and gestures would be understood in the key of listening. Such a proposal might be explored in relation to that of audionutrition that Tato Taborda will present to us.

Alice Poppe: Good morning, everyone! Thank you for being here. It’s great to be here together with Tania and Caroline, my collaborators in the struggles and affections of the project we developed at the women’s penitentiary Talavera Bruce, and Tato too, with whom I have worked on different artistic projects over the years. I am an artist, dancer, and professor of dance at UFRJ (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro), and I am also a collaborating researcher in the Graduate Program in Contemporary Studies of the Arts (PPGCA) at UFF (Federal Fluminense University). It is important to point out that this project we are discussing today begins with affection. Tania and I started the conversation about this project at a bar with Evandro Salles, who at the time was the curator of the Federal Justice Cultural Center (CCJF) and it was at the invitation of the CCJF that we began the project and with great enthusiasm created the circumstances to develop it. The process of implementing the project with SEAP (State Prison Department) and CCJF took a long time, we went through a lot of bureaucracy. Carol has been involved in this process since the beginning. Ever since we actually began the project, we see how much it has transformed our lives. The name of the project “Body, Gesture and Affect” shows how affect and affection are key dimensions. I have been thinking that although we wrote and formalized a project concept to embark on this endeavor, we rather saw it as being constructed in the day-to-day of what happens in the prison. Above all, we listen. Talavera Bruce is a women’s prison in Bangu and is a new territory for us. The sessions are on Mondays. Our preparation is really just to be available, to be in a state of listening so that we can propose. I think that’s our purpose. Initially we tried to plan a little more about what the practices would be like with the inmates, but as the process evolved, we understood that the practices needed to be created together with them there in that space, on that ground. A listening that was in tune with the territory. I happen to be in the middle of a course at UFRJ (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro) that I have been teaching together with Adriana Pavlova, about the work of choreographer Lia Rodrigues. In this course we have been exploring her work and we also interviewed her. In one of the interviews, Lia mentions something interesting about the work she developed over several years in the Maré Favela. The interviewer asks her: “What was your project when you joined the Maré Arts Center and how did you develop it?” She answered: “I didn’t have any predetermined project at the beginning, I arrived there to listen to that territory and understand what I could do in that territory.” Hearing this, I realized that the way in which Lia Rodrigues and her dance company approached the Maré favela was very similar to how we are approaching our work in Talavera Bruce and the environment of the prison with all its very particular characteristics. It is about listening to the space from the outset. This begins with the entrance to the prison itself, a process which is not such a simple thing. In general, things take a long time at the entrance. Every time we arrive there are different guards who ask different questions about what the “Body, Gesture and Affect” project is about. These are very crazy experiences that we encounter each visit, even before we actually enter the space where we meet the inmates. It’s a long journey, there are many things that happen. So, we are always very attentive to this, how to enter, how to behave, what to say and what not to say, how to communicate with people…It is a daily challenge, every time it’s different, because the people are also different, with different emotional states and we go about all of this in a very loving way, especially among ourselves. This more or less sums up our initial approach.

Caroline Valansi: I would like to thank everyone involved in the project for being here today. I am an artist and I’m currently finishing my master’s degree in art at UFF under Tania’s supervision, whom I would particularly like to thank, especially as I invited myself into this project!

Prisons occupy a place in the social imagination, often represented in a stereotypical way through media culture and discourses that barely reflect the complexity of life inside them. Being inside a penitentiary provides a unique understanding of what happens there. From my first visit, I realized that it would be very different from anything I had ever experienced or proposed.

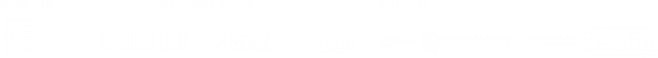

Also, this moment is special because it is the first time we are talking together about the project. Since we do not take photographs, do not record, and cannot bring cell phones or cameras, oral communication is our main tool for transmitting these experiences – which challenges us to narrate without resorting to images, so present in our daily practice. This project also connects deeply with what I have been developing for years. Although my background is in art, I work in constant dialogue with health professionals. At this intersection, I find new ways of listening and creating, where the body, gesture, and affect become living material for experimentation.

Tato Taborda: It’s all about listening.

Tania: Yes, absolutely.

Tato: The term audionutrition has to do with this expanded field of listening that includes but also transcends the physiological. The term refers to a shift from vision as the primary cognitive channel to that of listening, considering attributes such as receptivity, vulnerability, and availability; it is about defending what is in the world. Since the ear does not have eyelids, we cannot select portions of what surrounds us, as we can when we close our eyes, turn our heads, or even bury ourselves in the ground like ostriches do, because we would still hear. Listening to your stories about your experiences, and we will hear much more, I would like to suggest that the sound of things, the sound of the world and how it is expressly translated, gives more information about what is actually happening in the world than what can be perceived on the surface of the visible. I put forward this idea so that from a place of self-reflection, we can begin to investigate how much the sound of things expresses what is effectively happening with a depth and complexity inaccessible to vision. So, the idea of a cognition that has listening as its axis will necessarily constitute subjectivities in a different way than that which occurs with vision as the primary cognitive conducting channel. The vector of vision is directional and the act of looking is as arbitrary from the perspective of the one who looks, as it is limited by the surfaces that interpose themselves between the subject who looks and the object being looked at. I cannot see what is behind this wall, but I can hear what happens on the other side. So as a first reflection for this discussion, I suggest we reflect on how much sound expresses, denounces, and informs in a special way the nature of what happens in the world and, in some cases, perhaps in a more detailed and profound way.

When Tania brought up the idea of …

Tania: Choreolistening.

Tato: Which is a fascinating term and connects with what Alice once mentioned as…

Alice: …a radio-choreography.

Tato: That’s it, a radio choreography. So, you are not allowed to bring a camera into the prison, but can you record audio?

Alice: In principle, yes, but in another prison project that I am involved with we are having several problems with this.

Tato: Maybe this is something to work towards. At first, I imagine total restriction must be imposed, but I’d like to think that there is a path there to explore…

Tania: In Talavera Bruce, we can’t bring anything inside, but it’s interesting that you are encouraging us to question if there is really nothing that is negotiable. Alice began to talk about the bureaucracy of surveillance and closure, which is still violent, even though we haven’t experienced any specific situations of aggression. The bureaucratic management itself carries a violence that tends to paralyze us, which is why your encouragement to seek a space for negotiation is valuable.

Tato: I think this will come with intimacy and continuity, as you manage to somehow connect with the individuals who are there, in addition to the legal entities and the functions of inspectors, directors or guards, believing that there are strings in the inner wiring of individuals that might begin to vibrate as you gain their trust.

Alice: But it’s a paradox, because apparently, they want the project, and they encourage us to be there. They seem to like us being there, yet, at the same time, they seem not to want the project. There is something that happens in the institution relating to the guards and the entire prison system which, in some way, they want to prevent the work from being carried out. Perhaps because they perceive the sensitive action that it could provoke in those bodies.

Tato: Because it is a subversion, you are subverting an order that up until that point had been very clear. I imagine that these dynamics in that space generate an enormous degree of unpredictability, not to the point of causing a mass exodus, but, in a more subtle but no less powerful way, of modifying the micropolitical relations of that community.

Tania: Yes, indeed, and that presents itself very clearly in the prison and shows the violence of the institution’s punitive structure. Prison is an apparatus of punishment. Even as it responds to a demand from the federal justice system for the humanization of prisons – and it is curious that people talk about humanization because this clearly indicates how dehumanized they are already considered to be – and this translates into interest in projects like ours. In practice, however, there is resistance, sometimes made explicit in the speech of a guard about the inmates as being “worthless” for example.

Alice: Yes, I once heard a guard saying: “What are you doing here? These women are very violent, they don’t deserve anything!” With this they want to show that it doesn’t make sense for us to be there doing a job that they don’t deserve. It has to do with the punitive logic that is imposed there and is stronger than they are.

Tato: In these contexts people’s receptive sensors either do not exist or are obstructed, but perhaps, who knows, at some point you might think of some dynamic to be proposed for the guards…

Alice: We’ve already thought about that. I think it would be a great step!

Tato: The challenge of these dynamics is to propose ways to undo these blockages, these vibration-muffling devices that exist in those bodies due to a question of survival. It is completely understandable to assume that those who live in this environment shut down these receptors, in order to survive psychologically, because it is all very hard. At the end of the shift, the person returns home, has a small child, family, pets, plants to water, just imagine that disconnect? Perhaps, trying to access the individuals who take care of implementing incarceration a bit more. I don’t know to what extent and I know it’s difficult because there will be resistance, but perhaps there’s a more delicate and deeper way to act on the defense mechanisms created by those functions and, who knows, start to dissolve these self-defense barriers, these muffling devices. I don’t know, it’s an immense challenge and I imagine you must have thought about it at some point.

Tania: Exactly, we need help to think about this.

Public: How are the inmates reacting to this project? How are they responding?

Alice: We work with two groups: one that is “high security risk” comprising women that have been rejected within the prison itself. They can’t mix with the others in other cells because they have committed heinous crimes, so they are separated; and the other group comprises women inmates that are pregnant, here there is a lot of circulation. The pregnant women often haven’t been sentenced yet, or are about to have their babies and to be moved to another complex. The ones in the “Security” group are affectionate. They welcome us with great affection, they hug us, they thank us every time, many times. The reception is good and there is a desire to develop something, but there’s also many internal conflicts. Despite those in the “Security” group being in prison the longest and there’s more regularity, eventually someone different comes and we realize right away when there is a rejection and then some conflicts arise, or when there are delicate situations of withdrawal. But generally, the reception is very affectionate, they dive into the proposals and are very available and fun. In the case of the group of pregnant women, it’s a little more difficult because this is a group with a lot of circulation, as I said, some go out to have their babies, others are released. So, the number and who comes changes a lot. Sometimes we might work with two or three or, like last Monday, for example, where there were fifteen pregnant women. In general, pregnant women are more de-energized due to being pregnant and everything that it implies, headaches, fatigue, low blood pressure, and so on. Another thing that we don’t even need to go into too much detail about, is what it must be like to be pregnant in a confined place, where there is no sunlight and where you have to lie down practically all day. Very difficult! We also become de-energized and more tired when we work with them and we need to inject more energy than with the “Security group.” We always make this comparison, it’s inevitable. In the “Security” group, it seems that they are really very creative and more active and the pregnant women less so, because of all the reasons I’ve mentioned, and so the work is slower. It’s almost like searching for a body that has been fragmented.

Caroline: I think we should also say that the inmates in the “Security” group never leave the context of their group. They’re even on the margins of prison dynamics, like on Mother’s Day, for example, when they didn’t participate in the celebrations. They always remain apart.

Tania: They are also kept apart from activities that other inmates can attend that lead to a reduction in their sentence. There is a school and a kind of reading club, for example, as well as religious activities and religious services. But the inmates in the “Security” group are offered few activities, and this was the main reason why we chose to work with them.

Alice: They are the only cell in the prison that does not attend the school. That says a lot.

Tania: They are [doubly] trapped inside the prison.

Tato: Don’t they attend the school?

Caroline Valansi: Some do. The prison director told us a personal story about her own experience and how she wants to change certain patterns. She told us that she had once been a guard. At that time, she believed that prisoners should remain incarcerated, that punishment was the only option. Over time, however, her perspective changed, she studied law, became a teacher and returned to work at Talavera. Now, as director, she understands the importance of offering something that helps them leave prison in a different way — studying is one of them, having other opportunities is another. She talks about her own process of transformation, how she lived under the repressive model, but, over time, she discovered other possibilities. Within the limitations of this system, she seeks ways to provide something different for these women.

Alice: The inmates themselves speak well of her.

Caroline: Yes.

Alice: This is already really positive, as if she really wanted to develop something.

Caroline: At the beginning of the project, they came to us more because they wanted to get out of their cells than to actually move around. We tested different approaches to engage them. Little by little they began to understand the purpose of our encounters. Some have been with us since the beginning, and the difference is clear: today, they themselves make suggestions and encourage others to participate. It’s also interesting to make note of this trajectory of involvement. We worked a lot with the deconstruction of words, creating steps spontaneously and putting together improvised choreographies.

Tania: Improvisation.

Caroline: At first, the inmates had difficulty improvising, trapped within the limits of their own creativity. Many had to observe and copy the gestures of others in order to gradually free up their own movements. Over time, those who have been in the group for longer have developed a repertoire, they make suggestions and move more freely. Newcomers, on the other hand, often feel embarrassed. We work a lot on this issue of embarrassment. They hesitate, but little by little, they give in: “I’m going to do it, I’m going to scream, I’m going to move my body…”.

Tania: The codes of conduct are very restrictive both in terms of what is said and the kind of gestures that might be made.

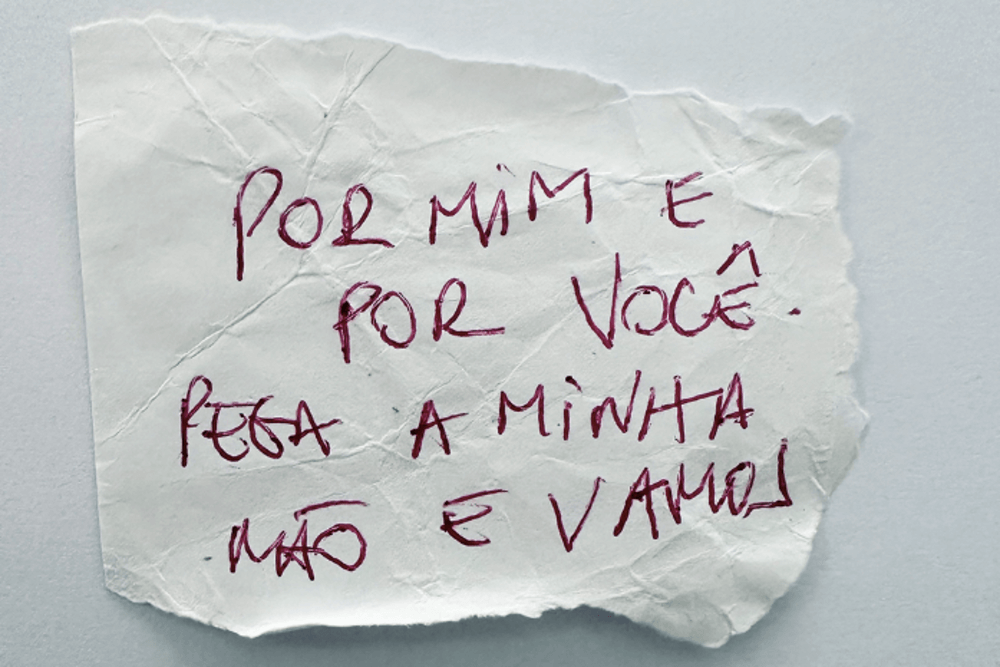

Alice: They have a way of moving around the prison. They lower their heads and put their hands behind their backs. The system choreographs their bodies in a very violent way imposing gestures of restriction and confinement of expression. It’s as if they weren’t allowed to open their arms, to look up, to breathe, or even to be able to say: “Ah, this is terrible.” We felt this the last time we proposed an exercise of emitting vowels with the expansion of the breath to stimulate the creation of internal spaces in the body, and we saw one of the women…Michelle, wow! We saw her noticing the creation of these spaces and the surprise of hearing her own voice! She is a very proactive inmate, from the beginning we noticed how her movement brought others on board, how beautiful! And they start to feel authorized to experiment something in that space, expressing their voice, their body.

Public: I’m really curious to know what the space is like and what you do there?

Alice: We normally work in a space called “Rebuilding Freedom.” It is a closed room, not very big. Occasionally, we have worked in a visitors’ lounge, a semi-open balcony that ends up being very dispersed, as it has contact with the circulation space of all the inmates in the prison.

Tania: Once we worked on the prison lawn under the sky.

Alice: That day on the lawn was very special.

Tania: Yes, it was really special. There was no available space for us that day, so we suggested that we could work anywhere, and we ended up outside on the grass. I think the next time we should suggest doing it there on a continued basis, because they are already extremely confined. The women were absolutely delighted to be there, even though it was still part of the prison. We were in the space right next to their pavilion, but there is a wall that prevents them from seeing that space. The discovery of the place where they have been confined, most of them for years, happened on that occasion, within the scope of the project. It was so lovely to see them looking at that corner, looking at the sky, and wanting to be there, commenting things like: “look at that cat!”

Alice: There are many animals there, including the last time, a possum. At first, I thought it was a mouse, it was a shock!

Tato: They have that rat tail…

Alice: …we saw it from the front, we couldn’t see the tail …

Tato: … with that very friendly face!

Alice: From the beginning, Tania and I thought about the idea of working with them on a resignification of that space, of thinking about ways of occupying the space beyond confinement, and understanding what the transcendence of a confined space could be. That day, in the open air, under a tree, we somehow had a return on this resignification of space, because they were able to look at the space in a different way, creating some pleasure in stepping on that ground and looking at that space.

Tania: And this suggests that, in fact, what we propose and what we bring is secondary.

Alice: Exactly.

Tania: Faced with the experience of a woman who says “look, there’s a cabin over there,” and you know that this is just three meters away from the cell where she lives every day, or of a woman who suddenly sees the sky – because, as we’ve already said, when they walk around in the prison they have to look down –, the importance of gestures in our proposal becomes clear.

Alice: Yes. They are just a pretext.

Tania: It’s not that what we bring is not important, but rather what happens goes far beyond that and sometimes reaches another scale. For example, pregnant women, when they arrive at the “Rebuilding freedom” room, where the basic structure of a beauty salon is set up, go straight to look at themselves in the mirror and say, surprised: “look how big my belly has gotten!” Then we realize that they don’t have access to a mirror in their daily lives in prison. And the fact that the project can provide an encounter with a mirror, especially for pregnant women, is perhaps more important than anything else we do there.

So, perhaps for us it is not just about listening to these women, but also about the demands that are presented there without even being stated.

Alice: The name of the project says it all: “Body, Gesture and Affect.” It is about people who can be affectionate with them, who allow themselves to engage with them and be attentive to them. In general, they are not looked at, nor cared for, and so we also create a connection with them so that they feel important. Some of them have already said this like: “Wow, I even forgot I was in prison.” Somehow, we create circumstances so that they can access their imagination and even their own bodies, in a way that they can really move away from that place and the way they are usually seen. So, I think we look at them in a different way. We care about them. Activities sensitize and promote sensibilities through experimenting with various devices, objects like balls, pieces of fabric, rubber bands, bags. We played with this idea of an object as a device that helps to access their body in a creative way.

Public: It would be nice if there was always a lawn.

Alice: It would be amazing.

Tania: Even with the usual heat – the prison is in Bangu, one of the hottest neighborhoods in the city – which prevents us from being directly in the sun.

Public: I find this project really interesting, really beautiful because it really humanizes people deprived of their freedom, who we end up dehumanizing, forgetting that there is a human being behind them.

Tania: What is your name?

Tato: Julia Tavares, she is a freshman in the class of 2024.1.

Tania: Yes, Julia, you’re right, that’s exactly it. Ever since beginning the project in 2023 I’ve been thinking about this. But when it first started, I was actually outside Rio, doing a post-doctorate in Argentina, so I accompanied the team through online meetings that took place after the visits to the prison. Since I’ve started to participate effectively, I”ve been asking myself: what does the project accomplish? Could it “(re)humanize” a situation of segregation and dehumanizing violence? Are we bringing something specific, or are we simply offering our availability? We are agents offering our availability – one of the few things that we truly take control of in life is being willing to go to a place, to be there with people.

I don’t think we bring them anything special, and perhaps the project forces us to think about this, to look for a different discourse than “wow, how cool, art is bringing something to these people.” The project leads us to think in a more systemic way, including dealing with the entire prison system, the bureaucracy of the prison system, the Federal Justice Cultural Center (CCJF) and the bureaucracy of justice. It is also learning to deal with this abstraction that is materialized in institutions like this, or with the aberration that is “justice”, especially in an unjust country like ours. We are lending ourselves to this, and in the end, perhaps they do more for us, in some way, than we do for them. This does not mean that the project has no value and does not make a difference, but it is an ethical issue: the refusal to put ourselves in the position of a project that brings something to people in need, breaking the logic that we have something that they do not have and that we can offer them.

Tato: Great, Tania, listening to you talk makes me think that this is how I see myself as a teacher. Isn’t it the same for you? In the sense that, deep down, more than bringing something, what we do is create environments that favor connections and the flow of perceptions and knowledge, in multiple ways and directions. All paths have keys; you take some that open doors that are closed, but you receive others that also open spaces that are inaccessible in any other way because they come from subjectivities different from yours. I think that what you are doing in the prison is not very different from the availability of being in a certain space as a teacher. You are not just bringing something. You are pointing your finger in several directions towards what moves you and, of course, not everyone will look at what you are pointing at, perhaps just at your finger. But at the same time, thinking of the classroom space as a multidirectional device, whoever interacts with you normally points to what is outside your plane.

Tania: Listening to you, the idea came to me that, in addition to thinking of availability as something that is given, we should also think of availability as anchored in a certain detachment. It’s not that we have something we’re going to bring to them, sometimes it bothers me that we’re three white, middle-class women supposedly bringing something to those women, who are mostly black women in situations of extreme sociocultural economic precariousness. This bothers me a lot.

Alice: Me too.

Tania: What we are trying to do in this improvisation, in a more or less intuitive way, is to create a space for our own detachment, understanding that it is about detaching ourselves from a position of power that means being there bringing something whatever that may be – art, gesture, affection, or our presence.

Alice: It is about the creation of circumstances for that space. In the beginning we were a little hesitant to even talk about where we are from, what we do. We spoke very little, because we understood that this could create a certain hierarchical distance, which could inhibit them in some way, as if we were in the position of passing on knowledge, given that this is a university project. Maybe we told them this once when they asked. This has to do with what Tania said and that I have been thinking about too, that more and more our strategies for creative activities are about a way of creating with them. We look more for what they can bring in terms of gestures than for us to bring ready-made gestures. For example, from the beginning we have been repeating a gestural exercise based on their name, which is a lot of fun. They bring very interesting gestures even when they are inhibited from making the gesture, which generates an interesting corporal attitude and they realize when we point it out that the inhibition is already the gesture itself. Last week we created a choreography based on gestures, we organized lines for them to play with each other’s gestures …

Tania: One made the gesture and the others imitated.

Alice: The choreography was created by them and it was really great. They had so much fun, they laughed because they were surprised that they could create a movement or even a choreography.

Tato: That reminds me of the final scene from Wim Wenders’ film about Pina Bausch, the line of dancers repeating different personal gestures…

Alice: Yes that line, almost like that, they are such different bodies.

Tania: I liked the word circumstance that you used to talk about the situation, because it implies movement, as in the word “to encircle.” To be in a circumstance is to put oneself in circular movement, it’s to circulate with and among people.

Tato: There is an environment circling around you, and I find it interesting that you don’t talk much about yourselves, about who you are out there. Maybe not talking about it helps to create a magnet, to ferment the constitution of a space of freedom, which disconnects from the past in the relationship with others, a non-place, an internal space.

Alice: Yes, it really is like this and this brings us closer to them at the same time that they get closer to themselves.

Tato: It is a capsule and this capsule can expand a lot, it can expand a lot according to the intimacy, trust, and learning that arise from the experiences. It is a universe that grows within that restricted space, walls with square meters, but it is a space of another nature.

Tania: And how would audionutrition fit in there?

Tato: Well, I keep imagining how much they know about what happens through the walls, how much they learn about what happens by listening.

Alice: So, you have to come there with us one day because the sound there is surreal. It’s a space subject to a lot of sound dispersion and there is a lot of noise. However, the women listen well and have a good relationship with what we suggest and propose.

Tato: A lot is happening …

Alice: Everything leaks.

Tania: There’s the hymns from the evangelical temple …

Public: I don’t know what audionutrition is.

Tato: It’s that very simple proposal that I mentioned at the beginning of our discussion, how much we can feed on what we hear, that is, understand more about what happens around us by listening than by seeing, where the making of sounds becomes a source of information, we do this normally, but it’s different when we do it more attentively. That’s the idea.

Public: What was it like for you to go there and experience this reality? Something which you never had contact with? How did you overcome your fear and these people’s fears? What was it like for you to overcome all these barriers to be able to work on the project?

Caroline: I arrived there with all this imagined idea about what prison is like, with a mixture of fear and curiosity, but also, a great interest in getting to know this context up close. Entering the prison is already a ritual: we follow the security protocols, we are searched, and we speak to the guards. But in the project, we deal with women and what they bring. We don’t fixate on what they did in the past; we are interested in what may arise in the here and now, in the present.

One time, right at the beginning, they put us in the church, right after a service. We did an exercise inviting everyone to close their eyes and, in pairs, be guided by each other. That was right at the beginning. Now, imagine closing your eyes in a place where distrust is constant. It is a challenging act even for us, who had just arrived there without any previous connection, and suddenly finding that we needed to be guided by someone. But that moment also showed us something important: the processes we propose are not just about movement, but about creating bonds. Bonding, trust is essential. Thus, we were establishing a relationship that goes beyond the activity itself. For these women, accustomed to an environment of surveillance and restriction, the project became a space where the presence of others ceased to be a threat and became something positive. Little by little, they began to arrive more willingly, more open to sharing their experiences with us. The work began to take shape, both for us and for them.

Alice: What Carol just recounted, the exercise we did in the church was a very powerful experience! I remember I was the one who proposed this. There, with my eyes closed being led by an inmate, I thought – wow, how crazy, the four of us with our eyes closed with the inmates guiding us through a wide, open space. I hadn’t realized how vulnerable we were, but it was great. What was impressive is that we felt comfortable with them. Sometimes it takes them a while for them to feel comfortable with us because they are also afraid, they don’t know what we are going to do, especially those who are joining for the first time. That day in the church we grasped the shifting dynamics of proposer and participant.

Caroline: One thing that people always ask me about and talk about is how heavy the energy is in prison. It’s not, of course, a great place, but the energy there is dynamic—it changes every day, depending on what’s going on. It can be light or dense, everything has an influence. During this process, especially at the beginning, Tania’s supervision was essential to help us understand our emotions and deal with these variations in energy, both those of the prisoners and our own.

Alice: We found ourselves leaving the prison shaken, tired.

Caroline: We were involved with whomever showed up, but we understood the importance of distancing so that the work could happen.

Tania: I never felt in danger, especially because I have worked in psychiatric hospitals, and compared to these, Talavera Bruce is very calm. Of course, some women there are depressed, especially the pregnant ones. And this is no surprise, because women in prison in Brazil do not usually have the right to intimate visits, unlike men in male prisons. Therefore, they did not become pregnant in prison; these are women who, unlike the rest of the prison population at Talavera Bruce, are not sentenced, they are waiting for a release order and many can be released at any time, which means this group changes a lot, as Alice already mentioned. I only realized recently that many women discover they are pregnant after they have been arrested and have to do routine exams. I then began to imagine the double imprisonment of a woman, who discovers she is pregnant and, because she is in prison, has no chance of having an abortion.

Public: What happens to the child afterwards?

Tania: At the end of the pregnancy, they go to another place which is a mother and child unit, where they stay for 6 months with the child after it is born.

Alice: Then the children can stay with family members, if they have them, or are sent for adoption, the babies do not stay with the mother.

Tania: It’s very difficult. It’s very hard.

Alice: We never went to the mother and child unit, Evandro [Salles – former director CCJF] went and told us about it.

Caroline: The theme of motherhood is a theme that appears with the women in the “Security” group too, those who have very long sentences, they have this longing for their children, for their families.

Alice: They talk about their children. Many have tattoos with their names on their bodies. There really is this relationship of memory.

Tania: Yes. But now I am realizing, listening to you, that for me the prison is calm, comparing it to a psychiatric hospital it’s super calm, but I think that’s because it’s a women’s prison. I don’t know if I would feel that way in a men’s prison, I don’t think so, I think that in a men’s prison I would feel in danger, I think it’s a gender issue.

Public: Did you choose specifically to work with this prison?

Alice: CCJF already had a partnership with Talavera Bruce and Oscar Stevenson, which is the semi-open prison in Benfica.

Tania: We learned from the curator Evandro Salles that CCJF was starting a partnership with this prison and that they would be open to the possibility of receiving proposals for projects. I developed a project proposal that CCJF welcomed with enthusiasm, assuming responsibility to cover costs only for the team’s transportation. But nothing is easy in this project. Not that it is difficult to be there with the women, on the contrary. The difficult part is everything that revolves around this work, institutionally. The violence in the prison system is so institutionalized that everything seems to contend so that the work does not happen.

Also, it would be great to at least have some funds to minimally pay the people on the team, especially the undergraduate students.

Alice: This overly bureaucratic relationship is very tiring. Sometimes we are prevented from doing things we would like to do because the bureaucracy really prevents it. So, just what Tania said about not having any support, makes things difficult. Right at the beginning we tried to make requests, like for example to use some materials for the practices. Wow, there was endless bureaucracy to get some large pieces of paper, to the point where we said, we are not going to ask for anything else. We bring some materials from our homes. Carol has wonderful materials, different types of papers, large sizes, and elastic fabrics. I take balls. This way we self-manage this process. In any case, having the CCJF provide transport is essential.

Tania: I think that from the beginning we also understood that it is not a problem with people exactly, but rather with a structure, that of justice especially, that of prison logic, which is violent par excellence. This presents itself not just in bureaucratic difficulties, but also in small things like the fact that every time we get there it seems the staff are not up to speed with the project.

Alice: It seems like it’s the first time: “Which project are you from?”

Caroline Valansi: “Are you the religious group?”

Tato: “Women pastors perhaps.”

All: [laughter]

Tania: It seems that nothing can be instituted. There is no routine for the inmates. You can’t establish anything. The institution is there precisely to suspend life and therefore time, the passage of time. One of the worst acts of violence is, perhaps, preventing inmates from having a routine. Can you imagine what it’s like to be serving a sentence over days or months and you aren’t able to organize your day-to-day life in such a way that time passes? Prison is an institution in which it seems that time does not pass. Everything there is somewhat crystallized. Just now that clichéd image of the prisoner counting the days on the wall comes to mind – maybe this is really necessary.

Public: It’s psychological violence. I remember a movie I watched that had a scene where one of the characters was arrested because he committed some serious crime and they put him in solitary confinement. It was all dark, a tiny place, really horrible and so to prevent himself from freaking out, so he wouldn’t go crazy, he would pick up a coin and throw it to the ceiling and then pick it up on the floor, and start all over again to mark the passing of time.

Tania: That’s a beautiful way to pass the time, making sound.

Alice: Psychological violence is really sharpened in that environment.

Public: Milton Gonçalves in the film Carandiru, which was a prison in São Paulo,the actor plays Chico, a character inside the prison who was supposed to receive a visit from his daughter and then she didn’t go and they made a joke about his daughter, so he attacked the guy on the spot.

Public: I wanted to ask a question. It’s not related to this subject, but a general question, why the body in your work? It seems to be much more about body movements than any kind of choreography per se, of course, these things are closely linked, there’s no way to separate, but why the body, why specifically the movement of the body in this project?

Tania: Very good question. What’s your name?

Public: Luana.

Tania: Luana, I can tell you what made me invite Alice and then read you the little excerpt from the project where we explain this, but I would like to suggest first that Tato talk about the sound of the coin hitting the ceiling and the floor. I think it is interesting to think about the place of sound marking and therefore allowing the passage of time.

Tato: Yes, it’s that tick tock. The prisoner created a time module. In the absence of any reference, he created a pendulum, a clock, a tick tock, something that materializes the passage of time.

Alice: Totally, if not it would be like a void of time…

Tato: …an eternity, he created a…

Alice: …a pulse.

Tania: Pulse.

Alice: Great, yes, because a pulse is soothing.

Tato: Yes! A pulse is soothing, because regularity is soothing.

Tania: Guys, this is beautiful. Pulse. Maybe now we should call the project Pulse.

Alice: Dancing without music can be very uncomfortable, so a pulse helps a lot, this is very cool.

Tato: Interesting to see that, in the absence of knowledge of the passage of time, the instinct is to create some kind of module.

Tania: How beautiful this is. Maybe this is a kind of ground zero for music.

Tato: In the beginning there’s a pulse.

Public: Music has bpm.

Tato: Yes, everything around us, visible or invisible, has a bpm too, from the smallest microphysical unit to the largest unit of the cosmos, everything has a bpm, a speed of vibration.

Public: Everything has a sequence.

Tato: What changes is the speed, the frequency of the vibration. You call it sound when it vibrates at a certain speed. And at other speeds, you call it light, radio, microwaves or the orbits of planets, but it is all vibration at different frequencies.

Tania: And us? People?

Tato: Yes, there are a lot of pulses at the same time. We are a multiplicity of pulses, but we were spared from hearing all these pulses. We would go crazy listening to the amount of pulses that are happening all the time inside us: breathing, circulation, the digestive system, glands secreting, hair growing …

Tania: So, there are psychoanalysts who work on music, like Jean-Michel Vivès, who propose the idea of a kind of sound “repression,” which would mark the basic differentiation between noise and voice necessary for someone to access language.

Tato: What is the meaning of the term repression?

Tania: Original or primary repression applies originally to mark the process of the advent of the subject, of the emergence of the subject. Primary repression is spoken of as something important for the person to experience in order to enter into language, to situate oneself as a speaking being among other speaking beings. Some psychoanalysts indicate a sound dimension to this in the initial differentiation between noise and voice, because, following what you are saying, we are enveloped in a mass of sound that has to be worked on, modulated. The word modulated is here used in terms of a privilege given by our perception to some units, considered significant, to the detriment of others, which would not be carriers of meaning.

Alice: To the point where, for example, we can ignore what is outside and here a pulse has to do with this possibility of being able to organize ourselves.

Tato: This is useful to reflect on our built-in ability to delimit units, to not perceive everything around us as a blur of atoms. However, when you make a sonogram, which is a digital photograph of a recorded sound, the image gives you the frequencies, durations, and intensities but does not clearly discriminate the units of what was recorded. It is interesting to think that if vision segregates, listening does not discriminate…

Tania: It’s not that these other sounds are totally eliminated, these other sound registers that are delimited in this operation. As the word repression indicates, they remain muffled, but they do not stop pulsating – to use the term that emerged in this conversation. What is repressed is not eliminated, but remains encrypted, retained, without being able to fully present itself as such. Perhaps one can think of art as that which sometimes, in a provisional or partial way, opens the way for what was retained to present itself as such. Do you think this makes sense in the sound domain, Tato?

Tato: That makes total sense in all domains. From your accounts, I first see how much personal courage you all have in engaging without any kind of map on this journey. For me this has a lot to do with the leap of the tick that [Jacob Von] Uexküll describes, of embracing uncertainty by making a leap into the void.

Tania: Great word, leap. Pulse and leap, so far…

Alice: Very good.

Tato: This experience would make a great extension project, since you are university professors. Based on this relationship with another institution, the CCJF, you can create an extension project at UFF or UFRJ, engage students, apply for scholarships, engage interns, and so on.

Tania: It’s great that [Tato as the UFF arts course] coordinator remembers this! It’s not that we didn’t think about doing it. Although, I confess that I have a lot of difficulty with university bureaucracy these days, but because we also didn’t know if the project could continue to count on the support of the CCJF, due to a possible change in the Center’s management. Everything about this project is very precarious and it is thanks to this agreement between the CCJF and the prison that the project is happening, because it would be impossible for us to pay for transportation. Also, from an administrative point of view, it is important that the project be part of an agreement with the CCJF, without a doubt.

Alice: SEAP [State Penitentiary Department] is not a prison but takes care of the entire prison complex in the city and state of Rio de Janeiro. So, SEAP is also an institution with all the bureaucracy typical of an institution with this level of complexity, which is why it took us eight months to get started.

Tania: But I think it would be great to transform it into an extension program both at UFRJ and in the arts course at UFF, for sure.

Tato: Because you have already done the most difficult part, and this space has already been created.

Tania: I would really like to have art students with us on this project, obviously, and I hope to be able to make this possible one day.

I would like to return to the question about why we were thinking in terms of the body. For my part, there was already a strong desire to work with Alice. We had often said to one another: “let’s do something together.” I think I saw the opportunity to present a project to the CCJF as the leap, to use the term that Tato mentioned a little while ago. What would come naturally to me would be to do some kind of listening/talking work, as I have training and clinical experience in psychoanalysis, in addition to working with art. But in recent years I have been looking for the leap elsewhere, and having Alice by my side has given me the necessary partnership for this experimentation. Despite always having had in my life a presence of movement and the exploration of corporal possibilities, I had never really proposed to do something in an expanded field of dance, let’s say.

I like to be able to try other paths. Tato, as coordinator of the UFF arts course, even invited me to teach class on the body next semester and I’m very excited about that.

Tato: It’s going to be wonderful for the 2024 freshmen.

Tania: For me this is an important challenge. I will try to invent a body, to begin with.

Tato: As [the philosopher] Claudio Ulpiano says, there is thought, the rest is all body.

Alice: For Ulpiano, the body is the unthought.

Tania: Regarding the reason for proposing body movement, I could also respond that psychological care already exists in prisons. But the truth is that I would not want to work at Talavera Bruce with a psychoanalysis project in the strict sense. I think that the issue of space imposes itself in a prison in a way that calls upon my body, a female body, that is, of someone who defines herself, identifies herself with the signifier “woman.” The idea of an enclosed body, and how work there has to take place in space, led us, with Alice, to think about an activity with gesture, affection and space, in a kind of expanded field of dance.

On our first visit, when we went with the CCJF team to see the prison, we noticed that when the “Security” group inmates came to talk to us, through the bars, we realized that they seemed to be very well organized as a micro-society. Imagine what it is like to spend years in the same space, in a single room, with many other women, in a cramped area and without any privacy. We realized that there was already a whole system of representation among them, that some spoke on behalf of all. A very beautiful thing in terms of social construction, which made us think of the project as something that would simply try to reinforce this construction.

I have a great desire to reflect on the ways of creating commons made especially by women in extreme situations such as that of incarceration, of the deprivation of freedom. So, we thought of the project, not as bringing something that they wouldn’t have, but trying to bring some contribution for a process that they themselves were already carrying out, betting on the affective constructions of social ties that can, undoubtedly, substantially transform the experience of each inmate.

Public: I wanted to ask a question that I’ve been thinking about a lot listening to you. You’ve been describing going through several portals in order to begin your work and then you create a portal for these women of another kind of universe, but you go through several until you get there. I wanted you to talk a little about that.

Tania: What is your name?

Public: Sérgio.

Tania: Sérgio, thank you for the question. If you don’t mind before responding to your question and these intersections, I would just like to ask Alice and Carol to talk about the issue of the body.

Alice: First of all, I want to say that Tania’s invitation has been very transformative. Being with her and Carol and the students in this project has been quite an experience. It is only with Tania’s support that I could have had the courage to be in this place. Also, as Tania said, in the first year she was not present, but she gave us support, she gave us a body to face these other bodies, this was fundamental. We had weekly meetings with her, because we needed to organize our own bodies to be able to go into the prison. We needed support. There is another project working in the prison coordinated by a university film program that the CCJF had also been implementing. At some point the person who coordinates this project contacted me asking if we could give them some emotional support. Anyway, just to say that Tania’s support brought the necessary listening body to the project in general. My tools as a dancer would not have been enough for that place.

So, at first, we began to think – with what body do we go there? There is a question that I think about regarding the marginalized body and the confrontation with those literally marginalized bodies. What’s left for those women? They only have their bodies there, they don’t have any material possessions, they have nothing. Their clothes are the same, they all wear the same white blouse. They have no objects and no relationship with the space of a house, for example. All they have is their body. So, the project is about potentializing that body. What we can do together and what they can understand together with us – it’s a back and forth, we bring something so that that body is potentialized and, in return, our bodies are also potentialized. We go through ups and downs. We also ask ourselves many questions that have to do with our lives and the way we build our lives. What happens is that we leave this experience with a different body and there is this common sense of creating together with them ways of how we can potentialize a body, regardless of whether it is a dance X, Y or Z, but rather to discover how we can potentialize our body even in the face of an environment that is prohibitive by nature.

Tania: It’s very important to hear you talk about this, Alice. You have a long history of artistic work that fundamentally takes place with the body, of course, in another way.

Caroline: Listening to you speak, I see how, the project being about the body brings me closer to them. It was in this process that I established the concept of “corpo transante” (swinging body), that is a body in flux, which crosses barriers, breaking with imposed limitations. In prison, where everything is rigidly controlled, allowing the body to express itself freely is a powerful act. Unlike other activities, movement does not require words or justifications, it simply happens, connecting each person with themselves and with others.

This concept manifests itself in this collective experience, where, through dance and gesture, the women move between the physical space of prison and the imagined space of freedom. There, amidst prison bars, we are able to create openings for another way of being, even if only for a moment. The dancing body does not submit completely to the prison; it finds cracks through which it escapes, resists, and transforms itself.

Public: The women are afraid to simply do this [makes a gesture of raising their arms about their heads] because they have to walk with their arms behind their backs, the prison is physical, but it also ends up being mental.

Public: There’s this prison of gestures, it really makes a lot of sense to work with the body.

Tato: I think that this is the great subversion that a work like this can do where contexts trap bodies and bodies are trapped…

Public: Trapped in a choreography.

Tato: They are trapped in a choreography, and while this internal space can be expanded with your work, their bodies are [still] trapped, but the being is free.

Tania: Space can be constructed. It can also be a bodily construction…

Tato: Yes, as well.

Tania: Activating and transforming relationships with space and other bodies in this context can also be liberating.

To return to what Sérgio asked, I wanted to say that I had never thought of the entrance as a passage through many portals. I find the idea interesting and I can almost hear the portals closing, plaf, plaf.

Tato: A very cinematic image…

Tania: There are several barred doors there, in fact.

Tato: How do you feel internally with each “portal passage”?

Tania: Funny, I don’t feel like I’m going through any portal. You know, when I’m there I feel like I could be anywhere with those women. But, at the same time, this is an abstraction that doesn’t hold up, because the institution is there, inexorably, and it has an effect on our bodies too. It can even prevent us from thinking and from having agency over the work. Alice has already mentioned that we deal with a large variation in the groups, especially the group of pregnant women. We do not even have the possibility of defining how many people will be with us at any one time, nor the means to guarantee that women who want to participate and have already participated before will continue to come. We suspect that our work might be used in a reward and punishment scheme, and that it may happen that someone interested in participating is not allowed to do so.

It happened that a guard decided, on her own, that all the women in that cell had to go to the activity, for example. We had a huge group that day, but not all of them wanted to be there. We realized that they had been forced. In the end it was great, we worked with that. We are increasingly subjected to an arbitrariness that is at the heart of what we consider as “justice.”

In this sense, the prison is at the extreme tip of a continuum that defines our society in general. It can be seen as a kind of miniature of society, in which the dimension of arbitrariness that is implied in every instance of power is made explicit.

Alice: It’s totally random. They call us the women of: “ah, are you from the body and soul project?” [Laughter]

Tania: They call our project “body and soul.” The actual name is “Body, Gesture and Affect,” but it seems difficult to accept a body without a soul. [Laughter]

Alice: No one knows who we are, even though we always say that we are from the “Body, Gesture and Affect” project. One day someone said: “Oh, you are from ‘Body and Soul?” We answered: “Yes!” We were so happy that the person at least remembered part of the title of our project and since then we joke that we are from “Body and Soul.” [Laughter]

I keep thinking that when we arrive at the space to work with them, we feel like we are in a very protected place, as if it were a very hard layer that we are going through. When we started talking today, I was thinking of an image of a hard stone that we go through and when we arrive it seems like a freer space, that’s incredible. Because there is a guard who doesn’t know us and doesn’t want the work to be done and calls another one who will get another one and another one who can get the key and the list of things to get, it seems like an endless saga. It takes half an hour just for all this to happen. So, it really ends up being a portal itself.

It seems like everything is very organized because it’s hard to get in there. Before you go in, they check your name, then you get authorization and from there the work begins. So, it seems like they want to show that there is an organization. On the first day we thought about what materials to take. We got there and the guard said: “Oh, who are you?” She could never find the paper that said the material we were going to take and we realized that these requests, although I imagine of minor importance for them, ended up being random [laughs]. When we understood that, it was liberating, wasn’t it?

Tato: A relief…

Alice: We took elastic, fabric balls, letters, millions of things and on the official paper they had there was only, I don’t know … What was on that paper that they never found, so it is a totally disorganized organization and, in that sense, we take advantage of that to be able to create our space of freedom.

Public: The doors as if they were a sermon of prayers.

Tania: Exactly, exactly.

Caroline: Despite this bureaucracy, none of the guards stay during the movement work, which nevertheless demonstrates confidence in our work.

Alice: We like it that way, because when the guards are near, the inmates are very different. Their hardened outer eye in turn hardens them.

Tania: I look at the “Security” women inmates and I know that many of them have committed heinous crimes, but I don’t see them as different from me, not at all. I believe that something happens there that’s between women, simply. Don’t you think? We create a playful atmosphere that brings us closer together, even though differences in socioeconomic status and race obviously still exist.

Alice: Totally. It’s like we are in this other place or non-place, right? So, we can be in what seems like a more horizontal relationship.

Caroline: With pregnant women, the relationship is different, as the group is always changing. With each new cycle, we need to build new bonds, which means we are constantly in the initial phase of closeness and trust.

Tania: It is not possible to establish continuity.

Caroline: With that group, it seems to stay in this place of not knowing what it is we do there. Of not understanding our work. The women in the “Security” group on the other hand, already know, have heard and/or commented among themselves in the cell.

Tania: Exactly, indeed sometimes elements that had been worked on months before reappear – that was the case with the gestures for the June festival [Brazilian popular celebrations held in June] that we once asked them to bring to the following meeting. Sometimes we hear that the work reverberates and is present in everyday life. Maybe today this pulse has already been established, but it took time. It is a pulse that is perhaps what makes the difference there, in a type of institution that by definition aims to thwart the pulse, to maintain a continuous line.

Tato: Like when one dies …

Tania: Yes.

Alice: But many have good communication between themselves. It’s funny that I went to work with another dancer, Laura Samy, for another project at Oscar Stevenson prison and when I got there they already knew about our project because some of them had heard from the other prison, how crazy is that? We got there already with the positive support that the work was good.

Public: I was thinking about this issue of not being able to record. I think it would be interesting to interact by taking photos, but I know it’s not possible, but maybe the idea of recording with audio would be interesting?

Alice: At first, we felt we should be writing things down on paper and such, but I think we rely much more on being aware of what remains of the exchange between us in a more oral way. The fact of not having a cell phone ends up helping us a lot because perhaps we wouldn’t pay as much attention to storing this memory even in the body.

Caroline: I believe that, in a way, we’ve already recorded this. When I write about this in my master’s degree, for example, these impressions end up being transformed into text, and now, when we discuss it here, we are also documenting it. I agree that the absence of cell phones keeps us more present, but I wonder: how can we expand this project beyond what we already do? But I also think this is wonderful. I realize that I pay much more attention there—to each person’s name, to what was said, to what happened—because, in the end, what remains is what I capture directly from the experience.

Public: I think it’s cool, normally we record so many things but, in the end, not really recording them.

Caroline: Yes, I think we end up forgetting many things, we are so used to recording everything all the time, without depending much on our own memories.

Tania: Maybe we can try to invent a way to inscribe experiences, somehow. What Tato said made me think that we really have to work more on the sound dimension that is present, perhaps even creating sound compositions that, if we can’t record them, we can sing – and dance to.

Alice: That’s possible.

Tania: Dancing might be a way of recording.

Tato: A language, a language that transcends walls …

Alice: Yes, a language.

Tato: Movement.

Tania: I like this idea that what the inmates’ bodies do could be repeated by us, or by other people.

Tato: This is very special.

Public: They only have their body, no clothes, nothing that is theirs?

Tania: They don’t have a mirror.

Public: This has stuck in my mind, I’m still thinking about it and I think it’s so interesting to have this opportunity to have this perspective on these women, society needs to know about this…

Tania: We can think of developing a piece, with the participation of Alice Poppe, Carol Valansi and Tato Taborda, which has the title: They Only Have Their Body …

Tato: How about Only the Body?

Tania Rivera: Only the Body.

Tato: That is so strong.

Alice: In general, we are very distracted from our body, because we have so many material things around us …

Tato: What Tania said about developing a piece evokes other wonderful texts that were written in prison, memories of prison. Maybe in some way, like letters written in prison, these experiences can leak out, right? Because there is no wall that can hold back their thoughts, expressed in the movements they make and made of language. That it may be released into the world! It would be the result of how those bodies engaged, of how much they produced. There is something very significant in this idea of this body-thought leaking out of those physical limits, as language, as a choreographic language, sound language …

Tania: What leaks out of the prison.

Tato: What leaks out of the prison.

Alice: … through the gaps.

Tania: Let’s do it!

Tato: Well, goodness, what a rich conversation!

I think that for today this is good enough, if there aren’t any more questions?

Tania: Yes, it was really good. This conversation reaffirms that only by listening to other people can we listen to ourselves. I think I can also speak on behalf of Alice and Caroline to thank you, Tato, for joining us and also Guilherme Vergara for inviting us to have this conversation – as well as Jessica Gogan, for encouraging us to transcribe and edit the recording of this panel.

***

Caroline Valansi is a visual artist and works at the intersections of art, education, and mental health. She holds a Master’s degree in Contemporary Art Studies from UFF (Federal Fluminense University) and investigates creation and collaborative experiences, currently primarily with the collective Ateliê entreaberto (Open studio of the in-between). Her work addresses corporeality, desire, and pleasure, proposing art as a tool for sensitive transformation. Her works have been presented at the Havana Biennial and are part of the collections of the Museum of Art of Rio, MAM Rio, and the IMS Institute.

Maria Alice Poppe is an artist and dancer who investigates the body and its poetic-political relationships with the ground, weight, and gravity from a hybrid perspective of dance and somatic education drawing on Angel Vianna’s methodology. She has a PhD in Performing Arts from UNIRIO and is a professor of dance at UFRJ. Alice has performed in many contemporary dance productions in Brazil. Her latest work, Celeste, choreographed by Marcia Milhazes, premiered at Palco Carioca at Dança em Trânsito 2025.

Tania Rivera is an essayist, psychoanalyst, curator, and professor in the art department at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF). She is also part of the Postgraduate Program in Psychoanalytic Theory at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Her recent publications include Lugares de delírio: arte e expressão, louca e política (N – 1 editions/SESC, 2023) and Psicanálise antropofágica: Identidade, gênero, arte (Artes & Ecos, 2020).

Tato Taborda is an experimental musician and composer, professor in the art department at UFF, and currently coordinator of the undergraduate art course. Author of texts and multimedia compositions, such as the opera A Queda do Céu performed in dialogue with Davi Kopenawa. He has numerous experiences collaborating with theatrical and dance performances and recently published the book, Ressonances: vibrações por simpatia e frequencias de insurgências (UFRJ, 2021).