The conception of the body based on the practices of Indigenous specialists from the Brazilian Amazon

João Paulo Lima Barreto (Tukano)

My interest in this article is to present the conceptions of the body based on practices of Indigenous specialists, such as those of my grandfather, and to show the network of relations that connects the body with a person’s “vital force,” bringing this knowledge into dialogue with my trajectory from an Indigenous community to the worlds of academia and biomedicine.

1. From Indigenous Community to University

I learned a lot in my childhood and adolescence living with my grandparents, especially with my paternal grandfather, Ponciano Barreto, a yai specialist (“shaman”). The yai is the holder of: Kihti ukũse (the set of mythical narratives of the Tukano (Yepamahsã); Bahsese (repertoire of formulas, words and expressions taken from the Kihti ukũse);and Bahsamori (the set of social practices associated with the bahsese and the festivals and ritual ceremonies throughout the annual cycle). My grandfather was a renowned cosmopolitical mediator, health care provider, and trainer of specialists in the Upper Tiquié River region [Northwestern Amazon forming part of the border-zone with Columbia], a tributary of the Uaupés River. The yai, kumu, and baya (plural: yaiua, kumuã, and bayaroa) are specialists who have undergone training, who are holders of knowledge and trainers of future specialists, and who practice the “profession” of health care and healing for individuals and the community. They are the cosmopolitical mediators and operators of kihti ukũse [mythical narratives], bahsese, [repertoire of formulas],and bahsamori [social practices]. ¹While they each have undergone similar training, they have their own specialty.

In community conversation circles, the talk almost always revolved around the Kihti ukũse and the bahsese —grown-up topics, as they used to say. But they didn’t forbid women with their children from sitting around them. For us children, making noise and running around was forbidden; our mothers demanded silence and recommended listening to the elders’ conversations.

During the conversations, they also discussed the dangers of diseases indicated by star constellations and pointed to the various dangers of river flooding, the abundance of wild fruits, summertime, and the abundance of edible larvae, called nihtiã. When discussing these dangers, they also discussed bahsese, the Kihti ukũse, and the formal discourses of poose ceremonies(special feast rituals) as well as modes of social organization—groups of older and younger siblings. Ultimately, these conversation circles were moments for updating knowledge. For the children, they told stories of animals, the boraro (curupira [legendary figure from Brazilian folklore understood to be a guardian of the forest]²) and the bisio, the saharowat, and the welrimahsã (all [mythical] forest human-like figures)³. They also discussed time markers, constellations, bioindicators, and the divisions of summer and winter.

Around the age of five, I began spending more time with my paternal grandparents. The house we lived in had two partitions: one part for the family room and the other for the kitchen, a space my grandparents preferred as their own. When I moved in with them, before I went to sleep, my grandmother would always tell me stories about animals like the agouti [rodent important to forest ecosystem], the crab, the inambu [birds that hold cultural significance] as well as talk about certain dangers that arose over time. During the day, when my grandfather wasn’t going to the fields to gather patu (ipadu [Amazonian coco leaves]), he would go fishing and often take me with him. When fishing, the order was to be quiet, no questions, no noise, just follow his instructions. After fishing, on the way home, on the way to the port, my grandfather would tell stories about the places we visited, the waimahsã (demiurges and organizers of the earthly world) who lived in the lakes, about the names of the rapids, the oãmahrã (subjects who built the terrestrial world) and other characters who helped to organize the world and create the future place of habitation of the waimahsã and humans.

Most of the time, when my grandfather told me stories, they were just introductions, brief and simple narratives, so that I could at least grasp the meaning of those Kihti ukũse. He also talked about the meaning of dreams and birdsongs and told stories about fish and the transformations of animals.

My grandfather, a renowned yai from the Upper Rio Negro, especially in the Tiquié River region, was in high demand by local residents to care for the sick. He practiced his craft with great dedication and zeal. One day, while discussing his training, he told me what his instructor had said on the day he graduated—these words have never left my mind:

Now you are trained. People will seek you out during the day, at dusk, at night, before sunrise or at dawn, in the rain or sunshine. They will seek you wherever you are, in the fields or fishing. Serve them without hesitation, without complaining. Never say “no.” You must do all this with joy, confidence, and enthusiasm, because you were trained for this mission.

My grandfather took this recommendation seriously, practicing his yai craftwith great respect and dedication. Above all, he loved what he did. Living with him, I was able to accompany him in his work. I often traveled with him, also accompanied by my grandmother.

Years later, I went to the Salesian seminary, where I spent six years. There I studied Seminarian Philosophy at the Higher Institute of Philosophy, Pastoral Theology, and Human Sciences (CNBB/NORTE I) for three years, spent a year in the novitiate, and took a temporary vow of chastity, poverty, and obedience. In 2000, I abandoned my priesthood and returned to study philosophy at the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), while simultaneously pursuing a law degree at the State University of Amazonas (UEA). I eventually dropped out of the latter program to enroll in the Master’s program in Anthropology at UFAM.

The period of back and forth between the Philosophy Seminar and the Philosophy program at UFAM was deeply influenced by my formation in Western philosophical thought. The Greeks’ explanations of the world, demiurges (gods), and the origin of things closely mirrored the way my grandfather had explained the world to me. When teachers spoke about Greek cosmology, it directly reminded me of the world of the Kihti ukũse, which I learned from my grandparents.

I often wanted to share my knowledge in the classroom—the ways of explaining the world and things from the Yepamahsã (Tukano) perspective. When I tried to tell them, the teachers quickly dismissed it as a myth, that, that space (the classroom) was for learning philosophy, or rather, a space for philosophizing. This happened both at the university and at the seminary where I had previously studied.

The need for dialogue between these worlds became evident when, in 2009, my twelve-year-old niece suffered a snakebite from a venomous snake near our community on the Tiquié River. The treatment generated significant conflicts between the Bahsese methods of Indigenous medicine and biomedical hospital models that recommended amputating her foot. Fortunately, we were able to be heard, and our treatment worked. However, the incident is an example of several similar cases throughout Brazil. This event inspired us to begin a process of collaboration toward the founding of the Bahserikowi Indigenous Medicine Centerin Manaus, a pioneering institution in Brazil. Consequently, the Center’s “origin myth” occurs in the context of the denial of Indigenous knowledge and therapeutic practices.

I was already aware that something needed to be done to deconstruct the long-held imagery of the “shaman,” as well as the (pre)conceptions about Indigenous knowledge, given what happened with the snakebite incident and the struggle we waged for the right to receive treatment in conjunction with biomedicine. Since then, I’ve been searching for ways to bring Indigenous knowledge into dialogue with science.

2. Anthropology as a Stimulus for “Thinking about Indigenous Thought”

I dedicated my academic studies, both my master’s and doctoral degrees, to highlighting these Indigenous concepts, more specifically those of the Yepamahsã (Tukano). This work has been developed alongside other Indigenous colleagues from the Postgraduate Program in Social Anthropology and members of the Center for the Study of the Indigenous Amazon (NEAI). Thus, my work does not propose a counterpoint to any of them, but rather seeks to promote, along with what has already been produced, a greater understanding of Indigenous concepts themselves.

In my master’s thesis, I defined waimahsã as humans who inhabit the domains or “environments” of land, forest, air, and water; who possess the capacity for metamorphosis and camouflage, assuming (dressing in) the form of animals and fish and acquiring their physical characteristics and abilities. I also described them as sources of knowledge, with whom the Tukano specialists (yai, kumu, and baya) must communicate and learn, in order to access their knowledge. Waimahsã are also beings who inhabit all cosmic spaces and who are masters of places responsible for the animals, plants, minerals, and temperature of the terrestrial world. They [waimahsã] can only be seen by a specialist, that is, a yai or kumu. These beings are, ultimately, the very extension of humanity, owing their existence and reproduction to the phenomenon of becoming, that is, to the continuity of life after death, thus representing the origin and destiny of humans, their beginning and their end. The categorization of the wai-mahsã, spelled with a hyphen, has been extensively researched and is often literally translated by anthropologists as “fish-people” (since wai = fish; mahsã = people), which led to the superficial understanding that fish are people for the Tukano. As I discussed in my work, fish do not possess anthropocentric attributes, that is, they do not have the status of people or persons. For the Tukano, fish never had, not even in their mythical origin, a human condition. On the contrary, their genesis is almost always related to what is discarded: scraps of wood, objects and ornaments abandoned by the waimahsã, and discarded and rotten parts of the human body, etc.

Following this research I began doctoral studies in 2016. My goal was to continue investigating Indigenous concepts through the lens of anthropology. To this end, I wanted to make sure that I did not invest in “field research” in the classical anthropological sense, nor even in incursions into Indigenous communities. Rather, I took advantage of the wonderful opportunity to meet with the Indigenous experts Yepamahsã (Tukano), Ʉmukorimahsã (Dessana), and Ʉtãpirõmahsã (Tuyuca) in Manaus, where I live, particularly those who offered their services as specialists (shamans) at the Bahserikowi Indigenous Medicine Center, which I conceived, helped create, and have been working since its founding in 2018. I invested my time in observing the bahsese practices of the kumuã at the Bahserikowi Indigenous Medicine Center. I lived intensely with them, participated in discussion groups about Kihti ukũse [myths] and bahsese [repertoire of formulas], served as the kumu’s interpreterin the consultation room, and observed treatment. Thus, the data gathered and the reflections produced in my research and this article stem from my learning with the kumuã at Bahserikowi, combined with my childhood experiences with my parents and grandparents, and my life in the community in Pari-Cachoeira, in the Upper Rio Negro.

It was during my undergraduate studies that I began to rehearse my intellectual crises: this desire to explore Indigenous knowledge and as I often say, to think Indigenous thought. But this was not, and continues to be, an easy task. Many people think that simply being Indigenous grants us the ability to “think differently,” to know how to express the difference in our conceptions of the world in contrast to the “Western scientific tradition.” In essence, the opposite is true: the more we advance in scientific achievements, the more scientific we become and the more we distance ourselves from our Indigenous worlds, our truths, and our Indigenous theoretical conceptions and practices. This makes it difficult for us to identify and develop our own concepts, or, less ambitiously, our unique way of seeing and thinking about the world through “our” lenses. In short, I dedicated myself to this exercise of reflexivity.

In that regard, for my doctorate, I decided to pursue research on the concept of the body based on the bahsese practices of specialists working at the Bahserikowi Indigenous Medicine Center. In this process, I chose to forgo traditional research tools such as a recorder, camera, field notebook, pre-made questionnaires, or clipboards. This was my decision. Based on my own experience, I thought that such tools intimidated or made people shy. Forgoing these tools requires a strong memory to retain valuable information and, without any assistance, transpose the filtered parts into records.

Without these tools, interacting with the kumuã at Bahserikowi was like stepping back into my childhood with my grandfather. The kumuã constantly spoke of Kihti ukũse and bahsese. Based on their experiences of treating patients at Bahserikowi, they shared with each other and the Center’s staff different cases of “illnesses” and their respective bahsese formulas.

In the morning, upon arriving at the Medical Center, the kumuã, while sipping their coffee, would discuss the cases seen the previous day. They would recount them in great detail, discuss their affections [in the Spinozian sense of changes in body and mind as a result of being acted upon], and explain how to articulate bahsese [repertoire of formula] based on a particular Kihti ukũse [myth]. These moments were only interrupted by the arrival of people who came to the Center for consultations.

Speaking in their native languages, they told stories about the beings that inhabit the cosmos and about the construction⁴ of the earthly world, that is the origins of humans after the world’s construction, and the stories of the beings who helped organize the earthly world. The Medicine Center breathed bahsese and Kihti ukũse.

On rainy days, the learning process was more intense and time-consuming. The kumuã, in the absence of patients, would spend hours talking about the Kihti ukũse and the bahsese to the Center’s young staff. Listening to them, I began to remember the Kihti ukũse my grandparents would tell me before bed, lying by the fire, while harvesting patu leaves, or while fishing. I also remembered the dangers and concerns of maintaining good communication with the waimahsã, the owners and guardians of these places, and to take care of the body as well as the importance of relationships between social groups.

I heard about the origin stories of animals, the transformations of people into animals, among many other Kihti ukũse. Today, I recognize how crucial the time I spent with my grandparents was. Listening to the kumuã tell the Kihti ukũse led me to hear my grandfather’s own voice. Like an open book, the kumuã ‘s wordsinvited me to explore the missing link between myself, an Indigenous person, and the outside world that I faced with great difficulty and where I tread carefully. The kumuã’s words gradually revealed a particular universe, one that was lived or yet to be lived.

When commenting on cases, the kumuã said that patients arrived at Bahserikowi very sick, suffering from the consequences of neglecting protection against waimahsã attacks, neglecting their diet, and failing to protect their bodies against the elements at the most vulnerable moments in their lives.

The kumuã had their own method and logic for telling Kihti ukũse and performing bahsese, explaining landscapes, the qualities of animals, the organization of spaces, and many other explanations about the world, beings, social groups, and social units. Conversations with the kumuã were true moments of instruction, teaching bahsese formulas for various types of ailments and for communicating with the waimahsã. Besides the public moments, there were also more private moments, especially during times of beer together. During these moments, the kumuã told me many bahsese formulas. But one day, one of the kumu told me something devastating. He said I was very bad at learning and memorizing those Kihti ukũse, bahsesee bahsamori, and that my mind was more focused on learning things from “white people.” This speech was an incentive to complete my studies and then return to learn bahsese with them. To do so, I would first have to undergo a “decontamination” of my body. According to them, my body, as a way of thinking and being, was contaminated by the things of white people, both biologically and mentally. All of this, they said, hindered learning of bahsese.

The kumuã were absolutely right. But I learned one thing: to understand that bahsese formulas carry within themselves truly Indigenous concepts. It was from this insight that I began to take the exercise of reflexivity seriously, using the Kihti ukũse and bahsese formulas as raw material for my anthropological, or perhaps, philosophical, analyses.

The bahsese formulae, for example, note healing substances contained in plants. For these experts draw on plant taxonomies. They also speak of the qualities of animals and natural phenomena, using these qualities to alleviate pain, protect the body, or transform it. I learned that bahsese are “metachemical” formulas for producing medicines and “metaphysical” formulas for producing protection, because the articulation of bahsese refers to the power to evoke the qualities of things, animals, plants, minerals, and other things that might alleviate pain, cure illness, and protect the individual or collective against disease and attacks from beings. It is a language of action: placing, potentializing, equalizing, uprooting, killing, and transforming animals. The Kihti ukũse’ myths recounting the origin of the world and the emergence of humans as well as the contents of bahsese formulas became the bases for the “reflexivity” that I developed in my research.

As I mentioned, contact with certain authors and academic works also motivated me to practice reflexivity. Bachelard (2008), for example, when he postulated that “poets and painters are natural phenomenologists,” really inspired me. Like poets and painters, I realized that Indigenous experts are natural phenomenologists, attentive to changes in human knowledge and the external world. They investigate and describe facts as experiences.

The transmission of the conceptual “trinity” of Kihti ukũse, bahsese, and bahsamori to new generations is done by specialists as if in an explosion of images. There is no past and future, only the present. The construction of ideas is made of words with a sense of the present tense. I believed that pursuing this language expressed by specialists in the form of Kihti ukũse, bahsese, and bahsamori, would be a possible path to “revealing” truly Indigenous theories.

Thus, I chose the Bahserikowi Indigenous Medicine Centeras my place of study, as a space for coexistence with the kumuã interlocutors – the holders of Kihti ukũse, bahsese and bahsamori – as a means of extracting from their practices truly native concepts.This position allowed me to delve into the world of kumuã and bahsese practices, and to grasp the notion of body beyond the spoken text. This was no easy exercise in reflexivity.

The second step was to translate the Kihti ukũse and bahsese formulas into Portuguese. At this point, the biggest challenge was processing the ideas using native logic, thinking like a native speaker, and then translating the thoughts and speeches of the kumuã. With this step completed, the next phase was to reread my transcriptions/translations and strive to make the text more coherent without losing its meaning—that is, to create a more didactic, rational, and consistent model for the purposes of scientific-anthropological writing.

The construction of collective texts among Indigenous students from the Center for Indigenous Amazon Studies (NEAI) proved to be an important tool for learning how to construct textual genres. Here, it is important to mention, as an example of collective production, the research and publication project, Omerõ – Constituição e circuito de conhecimento Yepamahsã (Tukano), published in 2018 by Indigenous and non-Indigenous authors from NEAI. The experience served to develop concepts and categories specifically related to the Yepamahsã. The process was based on a dialogical relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous anthropologists. The result demonstrated the following advantages: quality data collection, debates on concepts and categories related to Indigenous anthropological terms, greater involvement of advisors and advisees in the research process, and the qualitative systematization of Indigenous concepts. The mutual collaboration of ideas and understanding was one complementarity between the authors, minimizing the gap between the discourse of Indigenous experts and anthropologists.

Anthropology is now my profession of choice. So, in this sense, I can say that I am a “native anthropologist.” I follow the rules of the game, which are the same as those of non-Indigenous anthropologists in producing knowledge. However, my field of research is not, in fact, a world distinct from my own; rather, my profession is to translate Indigenous Pamuri-mahsã [Tukano term meaning people of transformation]knowledge into anthropological models.⁵

As an Indigenous person, a Tukano speaker, I have the advantage of being able to translate native ideas into Portuguese and apply them to the analytical practice of anthropology. Another advantage was the support, guidance, and mentorship of my father, Ovídio Barreto, who is also a kumu and the grandson of a renowned yai, a specialist who died thirty years ago, from whom I was fortunate to learn the foundations of Tukano thought during my childhood and adolescence.

While I imagine that many of the attitudes I encountered during my time with the kumuã might be similar to those encountered by someone who is not Indigenous, my relationship, however, with these experts is that of someone from “home,” who shares their cosmology and ontology. This is a key differential in the relationship between Indigenous people and Indigenous anthropologists. Here, the collaborator’s proximity and belonging to the group being studied is from the perspective of someone who is part of their continuum. For example, my father told me about the kihti ukũse [myths], the bahsese [repertoire of formula], and the bahsamori [social practices],from the perspective of teaching his son, me, the apprentice and anthropologist. Therefore, the relationship is one of knowledge transmission, of teaching someone who will, in turn, continue to operate with this knowledge in their daily experience and pass it on to the next generation.

It was precisely under the condition of transmission that the “revelations” I strove to identify emerged in the form of an epistemology, concepts, or a system of knowledge. A reflective stance on the kihti ukũse and the bahsese, parts of the Yepamahsã conceptual trinity, was the path I chose, believing it would best enable me to debate the truly “Indigenous” concepts. Thus, the exercise of reflexivity proposed here is to consider Yepamahsã [Tukano] thought and their way of understanding the body via a reading of bahsese practices, illnesses/injuries and their treatments.

3. The Constitution of the Body

It’s worth remembering that the study of the Amerindian body is not new to the history of anthropology. There’s no doubt that the body has been produced, fabricated, and constituted by society: cut, adorned, named, pierced, and painted. It also becomes something that lives, pulsates, feels, and establishes complex relationships with the world, transcending biology through its immateriality (Seeger et al., 1979). Many studies have been conducted to understand this subject, especially in the upper Rio Negro region, but the topic still remains worthy of reflection. Daily observation of bahsese practices, intense interaction with the kumuã, and participation in conversation circles led me to realize that the practice of bahsese was used as a gesture of intervention and care for the body, in addition to being an instrument of the production of daily life, a reference through which ideas and ethical and aesthetic values are produced.

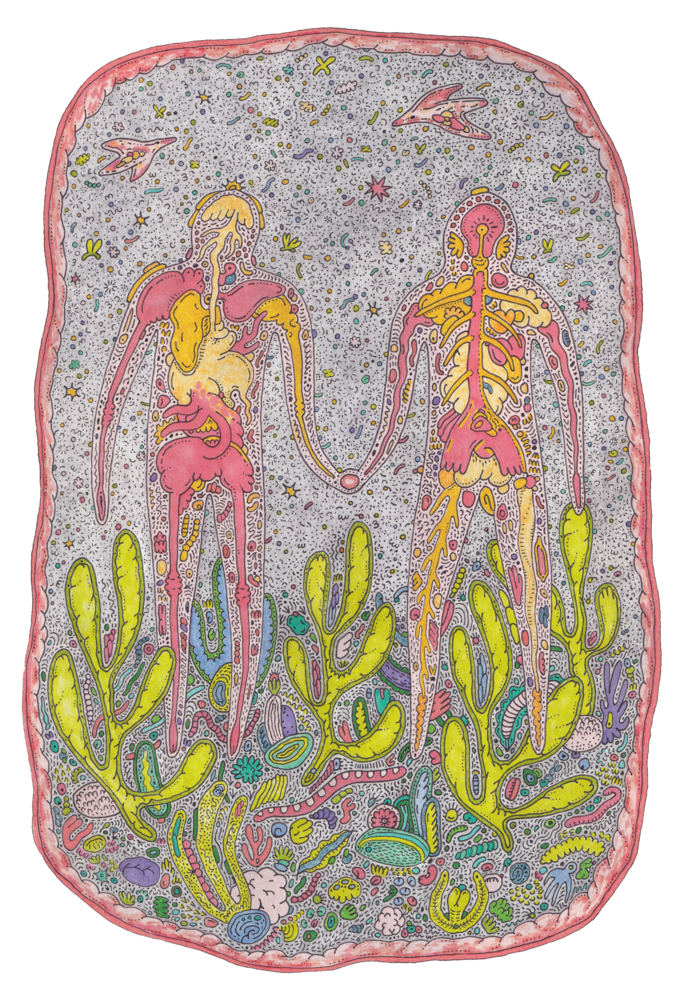

Beyond the structure visible to the eye, the concept of ethereal or immaterial elements that gravitate within the body is crucial, as it provides the conceptual basis for “metachemically” activating the qualities of the elements through the articulation of bahsese for health care and disease healing, and metaphysically activating the qualities of things and beings for prevention and protection. According to Indigenous experts from Rio Negro, the body [both] gravitates toward [and is permeated by] boreyuse kahtiro (“light/life”), yuku kahtiro (“forest/life”), dita kahtiro (“earth/life”), ahko kahtiro (“water/life”), waikurã kahtiro (“animals/life”), ome kahtiro (“air/life”), and mahsã kahtiro (“human/life”). All of this, in the special language of kihti ukũse [myths] and bahsese [repertoire of forumula], is summarized by the term kahtise.

Kahtise: the intangible elements that constitute the body

The term kahtise can have different meanings, depending on the context in which it is used and whether or not it is accompanied by a complementary word or phrase. For example, the expression kahtise nikã is used to mean that game or fish is raw, not cooked, or satisfactorily roasted for consumption. Another expression is kahtise nirowe, which means that things have their own life, such as light, forest, earth, water, animals, air, and humans.

An expression used by the kumuã when they spoke to me about the immaterial elements that constitute the body was manhsã kahtise. The expression meant that the forms of light, forest, earth, water, animals, and air were the constituent elements of the human body. The body is a synthesis of all the elements, a microcosm and a potentiality. Bahsese is one of the “technologies” for activating the body’s potential.

The kihti ukũse, the bahsese, and the bahsamori are also called mahsã kahtise, as they are considered essential knowledge and practices for the construction and care of the person. The kihti ukũse, the bahsese, and the bahsamori, therefore, are fundamental practices for ensuring the person’s existence and quality of life, which is why they are called mahsã kahtise.

When we say: mari kahtise nirowe, it means that which is part of us, that which belongs to us, that which constitutes us, that which is indispensable, that which is part of our body.

All these forces or elements of the body are called kahtise, essential for proper functioning and balance. An imbalance can cause disorders or even lead to death. Therefore, caring for the body is crucial for well-being, and this care is achieved by balancing the intangible elements that make up the body. For prevention, protection, pain relief, and healing, bahsese is performed byenhancing the intangible elements that make up the body.

There are seven types of kahtise that constitute the terrestrial world – boreyuse kahtiro, yuku kahtiro, dita kahtiro, ahko kahtiro, ome kahtiro, waikurã kahtiro, and mahsã kahtiro. The latter refers exclusively to the category of person. Mahsã kahtiro is the potential or “substance” directly related to a person’s name, injected by specialists through the bahsese processknown as heriporã bahsese, performed shortly after the child’s birth. The heriporã bahseke wame is also called omerō, a force within the body capable of evoking protective and healing elements and the qualities of other beings. Omerō, as a concept, designates the power of thought, intuition, and purpose of the Tukano specialist, the potential that inhabits and circulates within their body, thus connecting them to the movement of the universe and its creators. This potential is injected into the child in the act of naming, making him or her full of life and a member of the cosmic community. Omerō is a force that emanates from the “door of the mouth” of the specialist in his or her action on things and the world and in his or her communication with human and non-human persons (Barreto, 2018).

Boreyuse kahtiro (“light/life”)

This category relates to the element of light as one of the essences and powers that constitute the body. It refers to light originating from fire, as well as that emitted by the sun/moon, stars, lightning, lamps, clouds, or reflections. Each of these light sources has its own intensity and hue. Mastering the quality of light, its intensities and hues, is fundamental for Indigenous specialists, as it is from these that they use the bahsese to protect the body, such as to minimize the impact of light on a child’s eyes at birth.

Light serves many functions for Indigenous specialists. Its qualities, whether harsh or soft, can also be used to articulate protective bahsese to confront enemies. As the kumu Ovidio Barreto explained, one of the ways to confront an enemy is to empower the body with the qualities of the sun, spreading an intense light over the opponent’s vision. Just as a person cannot bear to stare at the sun for long periods, similarly, when one performs protective bahsese by invoking sunlight, the enemy will be unable to look at the protected person, given its intense brightness, potentially blinding them.

Unlike sunlight, starlight is used to cast bahsese over the body to enchant the person, making them beautiful and admirable. [Again] according to the kumu Ovídio Barreto, starlight also has the power to enchant people and instill admiration and empathy after the bahsese has been invoked.

The expression Boreyuse kahtiro means that the heat of light is a necessary condition for generating and sustaining life. According to experts, the body is regulated by body heat; its intensity determines a person’s well-being, and an imbalance can trigger a series of discomforts such as anxiety, restlessness, insomnia, lack of concentration, poor reasoning, and anger.

For the Kumuã, a place or space without light and heat is synonymous with the absence of human life, even though other life forms may exist. Boreyuse kahtiro, therefore, is a constituent part of the human body; its absence is linked to the body’s death. Furthermore, light can also be dangerous; it can affect other bodies positively or negatively, causing disease.

Yuku kahtiro (“forest/life”)

Literally translated, Yuku means “forest,”but experts use the term yuku kahtiro to refer to the “vegetable” potential that constitutes the body. That is, the set of plant life existing in the forest, which, in turn, possesses healing, protective, poisonous, and agential qualities. It is yuku kahtiro in the sense that plant qualities are constitutive elements of the body. Thus, the smell, bitterness, taste, sweetness, acidity, thickness, texture, plasticity, size, and hardness of plants and their fruits are qualities that can be activated and enhanced “metachemically” by experts, in the act of bahsese, to prevent, protect, and cure diseases, as well as to attack those causing discomfort and illness.

Mastering the properties of plants and their “taxonomy,” which constitute the domain of yuku kahtiro, is a sine qua non for specialists. The body, as already mentioned, is constituted by the qualities of yuku kahtiro, such as smell, bitterness, pungency, sweetness, and other plant characteristics. To protect the body from various aggressions, as well as to combat them, it is precisely these qualities that are activated by specialists in the practice of bahsese.

The idea that the human body is constituted of vegetal properties is not exclusive to the Pamurimahsã, that is, I have read in Jamamadi philosophy, for example, according to Karen Shiratori (2019: 178): “…the human condition comes from plants, that is, vegetality is the original condition common to humans, animals and plants.” This idea is quite evident in the Pamurimahsã [Tukano] but the difference lies in the conception that vegetality is one of the elements that constitute the body and not the only constituent or original element of the human. Vegetal qualities gravitate in the body and can be enhanced via bahsese.

The potency of the body’s vegetality also gives rise to other plants. Let us consider two examples: 1) the origins of the special plant for making musical instruments using miriã (jurupari[mythical forest demon and cichlid fish named for the demon]) understood as coming from the body of Bisio, and 2) other original cultivable farm plants which arose from the body of Bahsebo oãku. [These bodies refer to mythical forest human-like figures].

[Communicating with such figures is part of these curative practices] Bisio was responsible for training new specialists, as he was an excellent connoisseur of bahsamori [social practices] and is seen as the holder of musicality and dance techniques for accessing domains of knowledge and the rules necessary to become a specialist such as yai, kumu and baya.

The power of the plants the yagu carried was represented by the oãku’s bahsa busa (festive adornments and musical instruments), such as plumage, necklaces, dance staffs, body adornments, jaguar bone flutes, cariçú, yapuratu, drums, and other adornments important to the social life of the Indigenous peoples of the Upper Rio Negro. Thus, the Bahsebo oãku‘s own body was the source of plants.

Dita kahtiro (“earth/life”)

This is another essence that constitutes the body as a potential. It refers to the entire set of soil or earth types: rock, stone, mud, sand, and clay, in all their varying colors: black, red, white, and yellow. The body is also constituted by the essence of the earth. The qualities of the stones are activated via bahsese for the protection and resistance of the body. Their beauty, brilliance, and colors are qualities activated to highlight beauty and charm. The fertility qualities of the earth are activated to make a woman pregnant.

Dita kahtiro is also known as “mother earth” for her fertility, motherhood, fecundity, and generosity. Generous because she generates all beings, all things are born from the earth, and she provides nourishment and protection for life. Beyond her generosity, the earth is considered a mother (dita kahtiro) for being a space or place where the person returns as “matter” after death. The earth is the mother who receives and protects. Likewise, the heriporã bahseke wame, as a metaphysical dimension, also returns to dita kahtiro under a new personhood after death.

The person as a body is subject to “wear and tear” and attacks, say the kumuã. When discussing natural death, experts from the Upper Rio Negro often say that the body has grown weary of time and must rest. In the case of premature death, whether of a child or a young person, they say that this world was not meant for that person. In Tukano, they say: kahtiro pehatirowepã kure.

After death, the heriporã bahseke wame, as omerõ and metaphysical dimension of the body, also returns to the domain of the earth, but goes to the “house” called amowi (“mountain house”), in the case of the Yepamahsã (Tukano), which is in the region of the middle Tiquie River, a tributary of the Upper Rio Negro.

The finitude of the biological body is understood as the return to the other kahtiro, where it will continue to belong in one of the six main types of kahtise, that is, nodihta kahtiro. It is called ahpe kahtiri mohko, “new territory of afterlife.”

Christine Hugh-Jones (1979/88:113-134) shows that, for the Barasana, names are the only substance of the person that can ensure their continuity beyond death, because the substance of the soul is inherited in the name, while the physical body putrefies.

Unlike the notion of putrefaction, the Yepamahsã clearly understand that the end of the body is a passage to another type of kahtiro. Death, on the one hand, ends the body’s life cycle and, on the other, points toward another dimension. To die is to transform, not to die. The body returns to said kahtiro. The heriporã bahseke wame goes to another bahsakawi, the domain of the waimahsã.

In the daily practice of the people of the Upper Rio Negro, the different types of earth—black, yellow, white, and red—and the animals that have digging abilities are used in the bahsese processto plow and fertilize the land of the newly burned field. Once this is done, the planting of cassava and other crops begins on the prepared land.

Bahsese techniques are performed before the construction of a new residence. This measure is taken to ensure that the body never feels threatened by the earth, but rather feels it as an extended part of its body. As a result of this bahsese, the new home becomes a space of comfort and well-being for the family group.

Ahko kahtiro (“water/life”)

The “water/life” element is a term used to describe the importance of water, which constitutes the body and its transformational power. Water is conceived not only as a natural resource, but also as an essential component that constitutes mahsã kahtiro, yuku kahtiro, waikurã kahtiro, dita kahtiro —that is, water as an essential element for the existence of all other “types of life.”

By performing water bahsese, the kumu invokes the qualities of all types of water contained in animals, earth, air, and plants.

Pamurimahsã experts have a refined understanding of [different] types of water: ahko buhtise (white water), ahko soãse (red water), ahko ñise (black water), and ahko yasase (green water). When discussing the water element in the context of bahsese, the kumu Ovídio Barreto made the following comment:

After birth, mother and baby drink water after bahsese has been performed. This way, the child does not suffer from water-borne diseases, because otherwise, if they do not do this, the child, when breastfeeding, ends up contracting water-borne diseases and, when they relieve themselves, expel a mass similar to caxiri pulp. That’s how it works. (kumu Ovídio Barreto, 2017).

The fluid that constitutes the body and circulates within it is called opekõ and karãko kahtise, which can be understood as a fluid important for the maintenance of the body and human life. In the context of bahsese language [of formulas]and in the discourse of specialists, these two terms are frequently used. For example, in the following terms: Opekõ dihtará (Rio de Janeiro) – lake of cradle of human life; Opekõ dia (Rio Negro) – river of navigation of future humans.

There are others: opekõ wahatopa and karãko wahatopa refer to the artifacts used by a person; karãko doto and opeko doto refer to the capacity to sustain and generate life; opeko sopo weta and karãko sopo weta are fundamental terms used to “transform food into nutritious sources”; opeko sopo wai and karãko sopo wai are bahsese terms for the wai bahse ekase formula, transforming fish into nutritious sources. Thus, the words opekõ and karãko in the bahsese language are words that transform all things for well-being, “proteinization” of food, and the fortification of the body.

In the set of formulas of ba’ase bahse ekase (food cleansing), at the conclusion of the canonical formulas, are the words opekõ and karãko [operative] agents of transformation of food into substances that are healthy for the body, free from the dangers of contamination, and bearers of nutrition and strength.

Another important point, according to experts, is that water is an element present in all living organisms, which is why it is also called ahko kahtiro.

Water composes and moves the body along with the other elements. The kumu Durvalino states that most of the body is made up of water, which dissolves upon death. Thus, water provides life and protects the vital structures of the kahtise — yuku kahtiro, dita kahtiro, ahko kahtiro, waiku rãkahtiro, ome kahtiro, mahsã kahtiro. For these and other reasons, it is extremely important for all types of kahtise.

In the case of mahsã kahtiro, according to the kumuã, water is present in the form of sweat, tears, urine, saliva, eye lubrication, etc. And it plays a fundamental role in regulating body temperature. Thus, ahko kahtiro is a concept that encompasses the universe of water—body water, the aquatic realm, rain, and dew—with all its shades of color.

Waikuã kahtiro (“animal/life”)

The meaning of waikurã kahtiro refers to the potential animal quality that constitutes the body. That is, the entire set of qualities of animals and creatures existing in the terrestrial world, whether those that inhabit the land/forest or those of the aquatic environment. Their taxonomy and respective qualities are inscribed in the bahsese formulacalled waikurã bahse ekaro, from the larger set of ba’ase bahse ekase.

The body is potential: Because when the qualities of waikurã kahtiro are activated, the body becomes qualified by that animal or creature. First and foremost, waikurã kahtiro is related to animals with disease-resistant qualities and those with qualities used to empower the body.

Knowledge of the characteristics of animals is crucial for empowering the body during bahsese. During this practice, the animals’ qualities are evoked, such as their endurance, strength, intelligence, color, physical stature, coat characteristics, beauty, songs, vision and hearing, etc. In other words, all the qualities of each animal can be used to empower and protect the human body, activated during bahsese.

Waikurã kahtiro refers to animal behavior, with each group or species having its own characteristics, habitat, color, size, and specific diet, among other aspects. Mastering animal taxonomy and characteristics is essential for articulating bahsese.

Ome kahtiro (“air/life”)

This element corresponds to the air we breathe and its potential as a constitutive element of the body. The term encompasses all types and qualities of air, winds, and day and nighttime currents: strong and weak winds, hot and cold air, humid and dry winds. All of these types also compose and circulate through the human body. That is, air in its essence.

The ome kahtiro category is activated by the specialist using bahsese at the moment of the child’s birth, before the body’s first contact with air, breathing, and the outside world. The goal is to activate the child’s lung structure to function through their own breathing. According to kumu Ovídio Barreto, bahsese is like “starting the engine” so that the child begins to breathe on their own. This breathing is called opekõ kahtirida and karãkõ kahtirida which means breath of life.

Experts advise that physical contact with air also has its dangers; its charge and odor penetrating the human body can be harmful. For example, a draft or smoke laden with the aroma of roasting meat, fish, or fruit circulating through the body can affect a person, compromising their ability to learn and memorize.

The riskiest moments are: the first months of a child’s life, the spouse’s postpartum recovery period, the time of specialist training, the first menstrual cycle, and the moments after the use of kahpi and, after the use of miriam instruments (jurupari), during poose ceremonies (dabucuri). On these occasions, according to kumu Manoel Lima, the person must necessarily undergo bahsese.

The six types of kahtise discussed so far (boreyuse kahtiro, yuku kahtiro, dita kahtiro, ahko kahtiro, waikurã kahtiro, ome kahtiro) are sets of elements that constitute the terrestrial world, which can be summarized as bodies that constitute the terrestrial world, always in movement and transformation, that is, in a continuous becoming. According to the kumuã, all the elements are present in the human body. Thus, we can understand that the whole is the human body. The body, for the Yepamahsã, is potential: in constant movement and transformation, especially when activated by the articulation of bahsese.

The body, as a synthesis and microcosm, is an extension of the earthly world, just as the earthly world is an extension of the body. Thus, any imbalance caused by humans (pollution, devastation) directly leads to the imbalance of bodies, of people.

Mahsã kahtiro (“human/life”)

The notion of mahsã kahtiro, that is, the name of the person, is what qualifies a body as a person/people/human, as kumu dessana Durvalino Fernandes told me:

We are all animals, because our bodies are waikurã kahtiro. But we are endowed with heriporã bahseke wame, unlike those who are waikurã (animals). The heriporã bahseke wame connects us with other things that form our life force. White people do not have heriporã bahseke wame; they need to be injected with heriporã bahseke wame. (kumu Durvalino, 2019).

The marker of difference between so-called humans and animals, from the kumuã’s point of view, is the mahsã kahtiro injected by specialists through the process of heriporã bahsese. Humans are those who possess the heriporã bahseke wame, without which the body itself is waikurã kahtiro (animal life).

Literally, heriporã bahsese means “to name the child,” while heriporã bahseke wame refers to the name a person receives. And the term wame refers to the person’s name, given without the process of heriporã bahsese, which is a long and meaningful formula. Rio Negro experts say that the strength and potential of bahsese emanates from heriporã bahseke wame. That is, a force and a power of transformative breath.

Thus, heriporã bahsese is a process of injecting a name, and heriporã bahseke wame is the person’s name. Name injection is done through the long process of bahsese. Through long hours of concentration, the specialist chooses the most appropriate heriporã bahseke wame for that child, drawing it from the list of wame (names) of the social group to which the child belongs, and assigns it a name .

I remember well the day when kumu Durvalino Fernandes said to me:

A body without heriporã bahseke wame is not a complete body, because it does not carry with it the force of bahsese, of invoking protective elements and healing substances of the body, it has no power of bahsese, it has no connection with the oãmahrã, it has no connection with the territory, it has no connection with the social group and it has no connection with the cosmology of the social group.

According to experts, the body’s connection with all these dimensions is important because this union or connection forms a person’s life force. The balance of the individual and their group is understood through the web of established relationships, whether between social groups and waimahsã, or between groups and individuals. According to the kumuã, if everything is connected in a network of communication and interaction, the group will be in balance, and so will the individual.

***

João Paulo Lima Barreto: Indigenous member of the Yepamahsã (Tukano) people, born in the village of São Domingos, in the municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Amazonas. He holds a degree in Philosophy and a PhD in Social Anthropology from the Federal University of Amazonas. He is a researcher at the Center for Studies on the Indigenous Amazon (NEAI). He is also a founder of the Bahserikowi Center for Indigenous Medicine. He is also a coordinator of the Rede Unida [National Health Network Indigenous] Peoples’ Forum. He is a professor and a consultant.

References

BACHELARD, Gaston. The poetics of space. 2nd ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2008.

BARRETO, João Paulo Lima. Waimahsã – peixe e humanos. Master’s in Social Anthropology, Federal University of Amazonas, Manaus, 2013.

BARRETO, João Paulo Lima. Bahserikowi – Center for Indigenous Medicine of the Amazon: concepts and practices of Indigenous health. Amazônica – Journal of Anthropology , v.9, n.2, p.294-612, 2017

HUGH-JONES, Christine. From the Milk River: spatial and temporal processes in the Northwest Amazonia . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979/1988.

SEEGER, Anthony et al. The construction of the person in Brazilian Indigenous societies. Bulletin of the National Museum – Anthropology v. 32, p. 2-19, 1979

SHARTORI, Karen. The poisoned gaze: the perspective of plants and Jamamadi plant shamanism (middle Purus, AM). Mana , v.25, n.1, p.159-188, Jan/Apr.2019

¹ T.N. Given the number of Indigenous terms being used through the text and understanding that they may not be familiar to readers, we have opted to repeat the translation on various occasions throughout the text to facilitate readers’ understanding.

² Curupira is a Brazilian mythological being, the guardian of forests and animals, characterized by flaming red hair and feet turned backward to mislead hunters. There isn’t a single direct English translation for the name, but the Tupi-Guarani origin is often suggested as meaning “child’s body” or “covered in blisters/wounds,” reflecting its appearance or nature.

³ Other folkloric animals.

⁴ Here, he proposes the idea of the construction of the terrestrial world, as a counterpoint to the idea of God’s creation and the Big Bang theory. The Yepamhsã‘s explanation states that the demiurges constructed the terrestrial world from the elements in their possession, such as the yagʉ, shields, vines, mats, quartz columns, and tobacco (see Barreto’s master’s thesis, 2013).

⁵ The main peoples most familiar with the Pamuri-mahsã are: Tukano, Kubeo, Wanana, Tuyuka, Pira-tapuya, Miriti-tapuya, Arapaso, Karapanã, Bará, Siriano, Makuna, Hupda, Yuhupde, Dow, among others. There are other groups familiar with the Ʉmʉkori-mahsã, including: Dessana, Baniwa, Tariano, among others. Pamuri-mahsã and Ʉmʉkori-mahsã are explanatory categories of the origins of the social groups that inhabit the northwestern Amazon.