What is a procession? A History of the Grande Companhia Brasileira de Mystérios e Novidades

Interview with Lígia Veiga and Marília Felipe

By Jessica Gogan and Luiz Guilherme Vergara

Lígia Veiga[singing]

Good afternoon, people, I have a memory!

Good afternoon, people, I have a memory!

I only came now because they called me.

I only came now because they called me.

Pay attention to this warrior of mine.

Pay attention to this warrior of mine.

What I really want is to talk about the Brazilian people.

What I really want is to talk about the Brazilian people.

Hail, Master Margarida! She lives in Crato.

Are you recording?

Jessica Gogan

Yes!

Lígia and Marília, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us about the history and practice of the Grande Companhia Brasileira de Mystérios e Novidades [a street theater and public art performance collective] active now for 44 years. This interview is really important for MESA’s “Body, Ground, Heart” issue. It is truly precious to have this time with you both to talk about the Company’s work. Since this rich history could fill an entire book, we thought we would propose three key focuses for the interview as if it were a performance in three acts. The first act is an invitation to start in the middle – a deep dive into a key aspect of your praxis. The second is about the Company’s trajectory and the third is about the “know-how” you have gathered throughout this incredible journey.

[Afro-brazilian writer and activist] Nêgo Bispo spoke of what he called “beginning, middle, beginning”¹ when describing the day-to-day life of quilombolas [maroon communities] and their struggles against colonialism. “Start in the middle”, Deleuze also taught, as the dynamic unity of the event.² Modes of investigation, research, praxis, and street theater begin in the middle; walking, moving…

So, our provocation is to start in the middle and simply ask: What is a procession?

Throughout we will ask some questions, but I think mostly your stories will guide us. So, in principle that is it. An interview in three acts, starting in the middle, with the question what is a procession. Guilherme, do you want to add anything?

Guilherme Vergara

Is it clear?

Lígia

Very clear! I’m thinking about this “middle”, this spiraling thing, which has to do with our praxis… Which has to do with being in the middle of it all, like a navel. It’s difficult to say.

Guilherme

Let me explain why we are beginning with the procession. I first met you through one of your street processions. Processions that are gateways and surprises. A mutual entry point —life and procession— where our lives began to intertwine. The procession is both a form of public art and life, where we met and connected, a jumping off point for this beginning-middle-beginning conversation.

Lígia

I just remembered, Hélio [Eichbauer] used to talk about “necessary daydreaming.” Let’s do some “necessary daydreaming” he would say. That’s the procession. Because I think that the procession is a medium. A collective manifestation where there is no concern with theatrical precision. Not that it doesn’t require study and work. Every performance requires that. It requires time, maturity. But a procession is something that gives you the freedom to immediately relate outside and inside, to connect to the street, to passers-by, to the expression of what’s outside, but also the expression of what’s inside. In other words, you ritualize that moment of going out into the street with your character, with your instruments of ritualization, whether that might be a banner, a song, musical instruments, your voice, your performance, your way of walking, your peripatetic way of walking down the street. Because there is a give and take, you learn and also give in the moment, there and then. It is really very free, even though there’s a score—there is always a score, a musical score, a corporal score, a choreography, a way to involve and create an engagement with the audience.

Marília Felipe

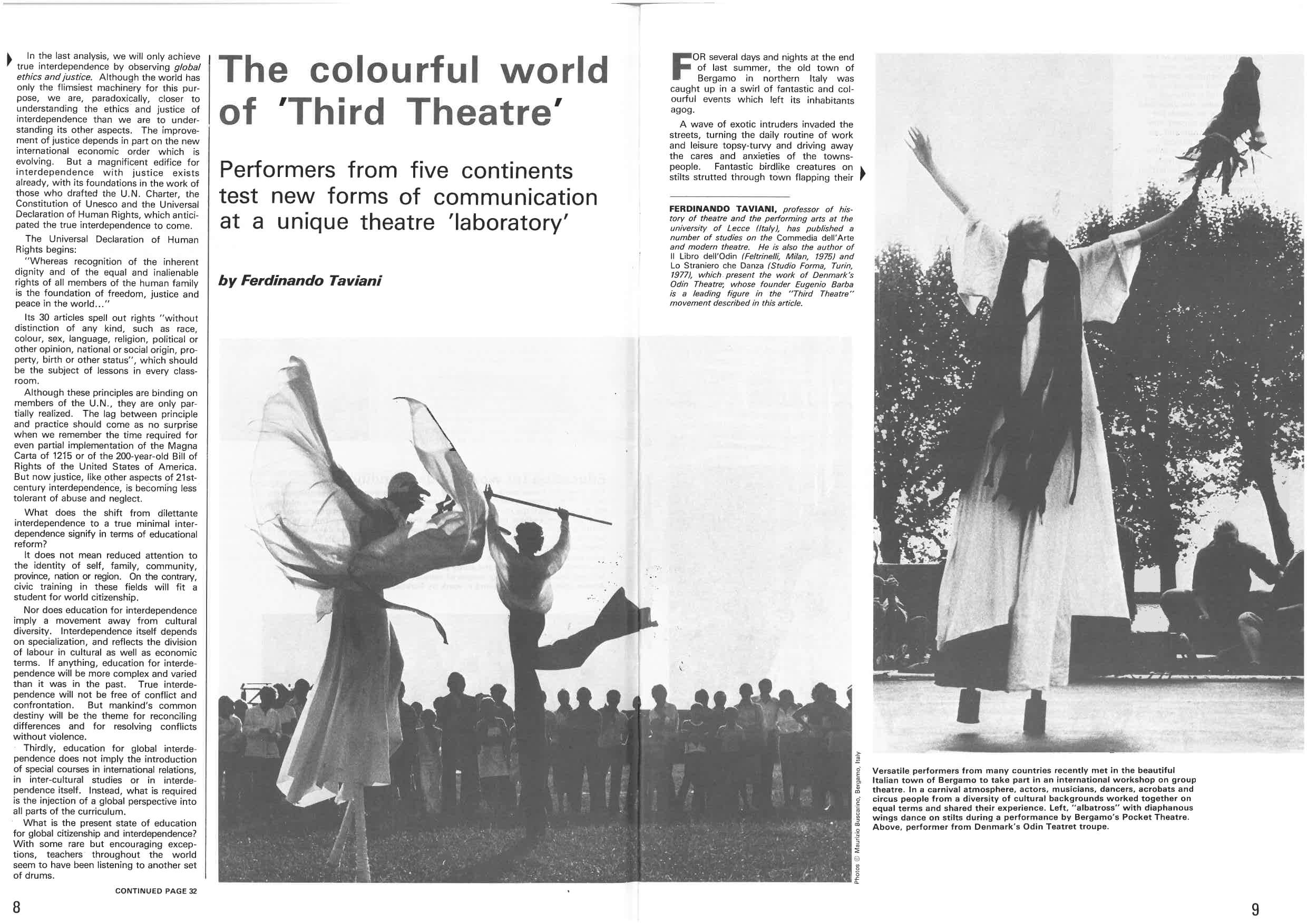

It’s about building relationships [with both publics and performers]. I remember when I joined the Company, you were doing the Saga [of Saint George]. You were staging Saga. It stood out because it began with a procession. You were already creating an atmosphere, a field of energy, as if imprinting a presence in space.

Lígia

Like a walking sculpture as Guilherme says.

Guilherme

The notion and the act of procession here is key. As a sort of intermediate instrument, it seems that your work might be along the lines of public art. Yet it is distinct, different from the kind of “public art” that focuses on public interventions as aesthetic objects in urban settings. The procession is rather an enchanted journey that brings together transtemporal and transcultural roots going back as far as the Middle Ages. It is not restricted to the aesthetic field. You speak of inside and outside. The street here seems the key for us to think about “body, ground and heart.” Because when we walk with you, we are drawn closer to one another. Little by little as we walk together, we become a walking sculpture. It is different from Carnival. The dimension of a procession, honoring a saint is something else. I see this sense of being an intermediary instrument as what makes the difference. It is very beautiful.

Jessica

Yes, definitely. I am reminded of the most recent All Saints procession. Before starting there was a group of, I don’t know, about 30 people, then as we began walking, in less than 100 meters, there was a kind of hurricane of vital energy and suddenly there were more than 300 people.

Guilherme

Like those cotton candy machines … It’s amazing.

Marília

Pure magic.

Lígia

The thing finds a way of organizing itself. I think a lot about what [street theater director] Amir [Haddad] says: “It is not the world that organizes theater. It is theater that organizes the world.” In processions and even in shows, I feel this a lot. For me, this is very real, very palpable. Things seem like they’re chaotic, but, actually, in the middle of it, the chaos is quite organized, in such a way that it organizes the world through that theatrical action at that very moment. Because a procession is a theatrical action, it is an act of collective creation. It is impregnated with a kind of layer…how do I say it… of incorporeality, a body that changes, of a rite, that has been lost and that, in that moment, is found again, we renew ourselves, put on another set of clothes. But this clothing, like a Tupinambá cloak, at the moment we wrap it around ourselves, we become that. We are not representing anything at all, we are being that thing at that moment. Of course, there are different levels. You can see a person, for example, who arrives to participate in the procession, who dresses up for it, then walks around unconsciously entering into that experience. But most people, especially those in the Company, prepare to enter another dimension. A key aspect of this is the use of stilts. Because stilts are an instrument, let’s say, of power, but rather in the sense of potency, of [possible] connections.

I have always used wooden stilts for sacred processions, in sacramental processions. African rituals are our sources of inspiration. The way they use stilts. We also use stilts in Carnival celebrations, presenting characters from popular cultures. For us, it is a way of positioning ourselves within the action, which forces you to address that very position. Firstly, because if you are not present, you fall. Walking on stilts, in a procession for example, creates a very different challenge for an actor from being on the ground. Not to mention the performances and presentations, but just talking about the procession itself, it’s a unique combination of giving your full attention, being available, and surrendering. It’s a special kind of care. If you were on the ground, you could play a lot more. That is, in the sense of a more relaxed time, let’s say. When you’re on stilts playing/embodying a character or are dressed in the costume of an Orisha [Afro-Brazilian religious deity], a saint or a figure that you want to bring into the procession, whether you are playing, dancing, singing or walking, on stilts you have to pay much more attention. You have to be totally present. We’ll talk later about the training for an actor to perform on wooden stilts. Because it is very different from performance without stilts. It’s something that puts you at risk. It’s always unknown. There’s always something you cannot predict. No matter how much you plan, if you lose your balance, you’ll fall. If you’re not paying attention, you could cause an accident. That’s why, for example, even in the Carnivals that we do, opening for the parades and floats, which we do a lot, we have a practice of not drinking alcohol. During Carnival everyone drinks, but being on stilts requires a different kind of presence from the people enjoying or performing at Carnival, especially if you are playing a character of a saint or Orisha, for example. It requires a different relationship with what is happening around you, with what unfolds during the procession. So, we speak about a kind of law, you might call it a law of street theater, where you have to work on presence. You have to work on yourself, your presence more than anything else.

Marilia

The spectator sees things as a scene. We however are “on stage.” This “on stage” is not everyday life. It is not an attitude you bring to the everyday. I am not going to dress up as [one of the Orishas] Oxum and sit here, for example. It is a state of being … It is entering a world that is not part of everyday life.

Guilherme

What you are saying is so powerful. Because we are talking about body, ground and heart. There is for me, in the tension and energy of the attention of the person who is up there, the question of balance. On the one hand, this transforms itself into a powerful aesthetic experience for those watching, and, on the other, it symbolizes the incorporation you just mentioned. The choice of suspending and verticalizing these beings – the Orishas, saints, or characters from a special story – so that they are at a height higher than we are normally, they assume a symbolic height. This experience of verticalization is really a kind of incorporation. The performer, just like with Hélio [Oiticica]’s parangolé [performative capes and standards], when he or she puts on stilts they incorporate. Rehearsals then are to prepare performers to incorporate.

Jessica

One thing I find super interesting about the parangolés is this dimension of what Oiticica called “watching and wearing.”³ As we wrap ourselves in a cape, we are simultaneously embodying the experience of wearing and that of watching, as we watch others do the same. Hélio’s proposal completely changed the notion of an art experience focused on individual contemplation. Esthetic experiences are about embodiment, to be felt and witnessed together collectively.

Guilherme

Hélio talks about incorporation. In the transtemporality of the processions you really incorporate all temporalities from Orishas to historical characters. Then there is the juxtaposition of this on the asphalt. There, on the street, there is an “enchantment”, something genuine, authentic. This continues to impact me ever since the first time I saw one of your processions. I was at Praça Mauá. All of a sudden you were all there. I remember saying to myself: “What is this?” It was like a cloud of enchantment passing by. This really grabbed me. But I want to return to something you mentioned earlier regarding African influences. Did you draw on any African reference when you started to use stilts? I don’t know if I understood correctly, is there a reference? Connected with Afro-Brazilian entities?

Lígia

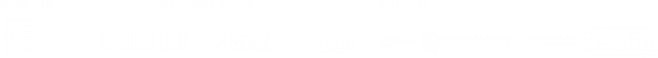

Actually, these things are very intuitive. They’re not programmed. Like, let’s do it like this. In the beginning, I didn’t have any references. I started working…I’m talking about myself first and then we’ll get to the Company. Now, yes, we use several references, but initially there were no studies on this. Then, of course, I started researching, seeing things, and meeting people. When I talk about Africa, it’s because, well, I had a certain fascination. This thing about wooden stilts… there’s a story there … I was a girl, I was 17 years old and I bought that magazinepublished byUnesco, The Unesco Courier. I have kept them to this day. Do you remember this magazine? The UNESCO magazine? [One issue (January, 1978)] had a cover that was a Balinese figure dancing and there was a feature article about street theater. This fascinated me. It was about a street theater festival in Europe where there were several wonderful groups that had come together. Groups that I got to know later. I read it and was fascinated. In the article, there was a picture of a person performing on very high stilts, not small ones, nothing like that. They were the height we work with now. The person on stilts was dancing with another person, also on stilts, waving a kind of large baton. They were all in white. It was a very charged, very beautiful thing. Seeing that image, I said to myself: “I want to do that.”

At the time, I was in my first professional performance group, Grupo Coringa [a contemporary dance group founded by Uruguayan choreographer and dancer Graciela Figueroa, following a workshop she taught at Parque Lage (School of Visual Arts in Rio de Janeiro) that in the 1970s became one of the most important contemporary dance groups in the country]. Graciela was queen of the dance festivals that took place in Bahia, in Salvador. We would go there every year. There she had the opportunity to do whatever she wanted, any type of set, whatever, so I asked Graciela to ask the carpenter who was there at the Castro Alves Theater to make me wooden stilts.

Guilherme

Is this in the late 1970s or 80s?

Lígia

Yes. It was during the middle of the military dictatorship (1964-1989).

Guilherme

That’s an important detail.

Lígia

The performance was part of the Bahia contemporary dance festival. It was the best festival in the world. It was incredible, like an oasis. Because all the companies met there and held workshops. We spent weeks there. We had classes with anyone we wanted. Anyone could take classes with anyone. Every day we watched performances. We nourished ourselves. We lived together. It was an incredible thing. Something that doesn’t exist anymore at festivals. They call you to do a performance, you arrive on the day and the next day you have to leave. It’s rare when you can stay. Everyone stayed there.

Marília

Everyone slept together, in a big room. You chose who you would do workshops with in the morning and in the afternoon, you would do some rehearsing with whoever you wanted and at night there were presentations, and in the early hours of the morning…it was crazy! [laughs] You didn’t sleep. By the end of the second week, you were sleeping on the move in-between things. That was it.

Lígia

It was marvelous…1976 and 77…

Guilherme

Better than Woodstock! It had spiritual symbolism, right?

Marília

It was Bahia.

Lígia

It was the heart [of everything]. The 1970s in Bahia were crazy. Anyway, I asked Graciela to ask the carpenter at the theater to make me wooden stilts. I had an idea for a scene, at the time we were inventing everything at the last minute! It was going to be a choreography where I would perform on stilts because I thought it would be interesting to work with this thing from another dimension within the shows that we put on. An interesting thing is that I was living with Graciela at that time. She taught at ASA [Associação Scholem Aleichem] there on São Clemente in front of Casa de Rui Barbosa and we had a lot of freedom to do a lot of things there. So, I had already started experimenting and developing ideas within the Grupo Coringa shows. Why am I telling you all this? Because this is when I came across a photo on the cover of the Unesco Courier magazine of performers with Balinese masks. In it there was a feature about street theater in Europe, something that no one was talking about in Brazil at the time. No one. This was where I first saw the image of performers on stilts.

Many years passed, about ten or twelve years, I don’t know. I ‘m going to skip the story a bit so it doesn’t get too long … So, I’m working in Europe with a street theater company and something magical happens to me. I was already totally in my element, happy, and feeling so lucky to be working with this incredible Italian street theater company. The two Italian directors were from Tascabile Theater of Bergamo, a great theater group, one of the most recognized groups, a super reference. The group still exists, but many have already died. There were two directors. One director, Enrico Masseroli, who worked with Balinese dance and masks. The other, Ludovico Muratori, taught how to perform on stilts and stilt dancing. He was a great master for me. He was Sicilian and a teacher at the Tascabile Theater. He also worked with several other groups in Europe. It was with him that I learned the technique to perform on stilts. I had no technique at all. I just went about it intuitively. There, working with him, I learned the stilt technique. A technique that, of course, I recreated in my own way. But the technique, as he taught me, is what I pass on to others. Because it is unique. People walk and perform on stilts in a thousand ways, but Ludovico’s technique I think is the best. He became a great master.

So anyway, I’m working with this group Teatro Pirata, where Enrico, whom you met, was one of the directors, and Ludovico, the other one, was the stilt master, who I was working with. At the time I had a boyfriend who was a physicist and he was also one of the acrobats of the group. He also performed on stilts, among other things. He worked at the college. One day I was in his office and opened a drawer, I saw a little pamphlet in Hungarian and then I saw that photo from the UNESCO Courier magazine of people on stilts that had one day made me dream “I want to do that.” So, I turned to Walter and said “what is this here?”

He said: “That’s my Hungarian acrobatics teacher. I was there just now taking a class with him.” I said: “But what about this photo here?” He answered: “Ah, that photo is of Ludovico. It’s Tascabile.” In other words, that photo that had brought me to do what I was doing at that time, where I was fully in my element, the photo that had brought me there, that photo was of the very director that I was working with. There he was, that guy dancing in white. It was Ludovico from the Tascabile Theater. He and Enrico left Tascabile to form the group [Teatro Pirata] with whom I was working at that time. Well, I already felt that I was living out my destiny, but when I saw that photo, I said: “I can’t believe it!” I was living what I had dreamed about!

Guilherme[singing a line from a song]

“Tomorrow came yesterday …”

Lígia

Tomorrow came yesterday and yesterday will still come.

Guilherme

How amazing!

Jessica

Spiral time.

Guilherme

Yes, one of my students this morning mentioned the work she is doing in Bahia and how they are using Leda Martins book as a reference [Performances do tempo espiralar: poéticas do corpo-tela, (Spiral Time Performances: Poetics of the Body as Canvas),2021]. She cited Martins: “Dance is a way of organizing the present.”

Lígia

I’m going to write that down.

Guilherme

Time is suspended. The present moment is freed from a routine, set loose from norms, it is suspended. In the midst there are enchanting creatures on stilts. My students were amazed at the last procession. They drew pictures. Everyone sang to them in that moment of concentration [before the procession began]. The processions invade the time of the street, of carhorns, of routines, and everything else, with dances of enchantment, creating what you call kairos time.⁴ It is about an organization of the present, an immersion in the presentness of time. As you say the performer on stilts has to be fully present in the present time. As spectators/participants, we watch and walk, and we also find ourselves completely taken with the powerful irradiating enchantment of these performers.

Lígia

Here, we enter a kind of timeless time, that is this connection, what happens between us and the public. Those who come to watch and passerbys. For example, this past Saturday, a young guy came with his daughter, I think she was about six years old, more or less and said: “I was passing by and I never would have expected anything like this! I’m impressed! I came to do something else and suddenly I saw this procession entering the square and I followed it and stayed until the end.” They were delighted and wanted to know when we would do it again. As I am saying this, I am also thinking about the many many times we’ve been to the back ends of the world, where supposedly there’s nothing, where nothing is happening, where no one goes to do things. For example, years ago, we went to do some research on birds, specifically the popular Amazonian operettas about birds that are traditionally performed during the winter June festivals. These only happen in Belém. It was a place called Mosqueiro. We went to do research for a new piece called Uirapuru, o cantor das florestas (Uirapuru, the singer of the forest). This was a tribute to Dona Noêmia Pereira, a composer of these “bird” songs, and to all those guardians who, with love, work and wisdom, keep this tradition of the “June Bird” alive.

The first time we went there we went to the home and street corner of where Dona Noêmia had lived. She had already died, but her family was all there in this little square. People said: “Nobody ever comes here. There is nothing to do here.” However, that day everything changed. We did a play there and all the children from the neighborhood went there. They were enchanted by Marília performing Mother of Water, like a mermaid …

You should tell it, Marília… it’s a beautiful story…

Marília

Yes, I can quickly talk about this magic. I do a performance of a persona that is a Mother of Water, a Iara [a mermaid figure from indigenous Amazonian folklore]. In the performance I use a transparent, semi-shiny fabric and stay in the one place, as if I were in water, emerging, a figure with flowing watery hair, as if everything was water. It’s a way to create an illusion of water, as if it were a river. Then I see a group coming, I can see from afar, there’s about ten children, like six years old, all together, all boys. They come walking towards me. Then one comes up to me in the middle of the performance and says to me “Aunt Iara” and he starts asking me something. “Aunt Iara.” I was so moved that I started to cry, at the beauty of that situation, it was the most beautiful thing, because Iara is an entity of their universe, she’s from the Amazon.

Lígia

This was in Mosqueiro, on the island of Mosqueiro, on the way to Marajó. People said there was nothing to do there but Dona Noêmia Pereira’s entire family was there and together we sang her compositions. The songs we sang, like other compositions from the popular operettas of Belém do Para, were created by Dona Noêmia, who sustained her family by cleaning houses and cooking for others. It’s a long story. Dona Noêmia is no longer with us. She has already gone to the future. I never got to meet her, but I heard her singing one of her songs in a collection that I loved, Music from Brazil, put together by the anthropologist Hermano Vianna. Vianna did something very similar to [the poet, ethnographer and musicologist] Mário de Andrade. He collected songs, but from very different times, things that no one knows, from various places, deep in the interior of Brazil and he made a collection of four beautiful CDs. Mário de Andrade was unable to do this.

So, I used these songs collected by Hermano Vianna and combined them with other references. Our show Uirapuru is a fusion between Villa Lobos and Dona Noêmia, the symphonic poem Uirapuru by Villa Lobos and the songs of Dona Noêmia, telling the story of the Uirapuru [Amazonian bird similar to wren (musician or organ wren) or manakin].⁵ It’s a ballet on stilts.

I’m telling you this to give you a sense of what I went to do in Mosqueiro for Dona Noêmia’s family. They had stopped doing the tradition of “June bird”. When we returned to Belém, after having researched and anthropophagized what we had received from them, we brought the tradition back to them. This rekindled their desire to continue [the tradition] and they started doing it again. It’s been a while now. So, for us this gives another meaning to do what we do. It makes even more sense. Do you know what I mean? Because we went there, did research, worked, and met them. There was a bird festival that hadn’t happened there for a while. But we went to the place, got to know them, and presented our show Uirapuru at the cultural center where they had held “Os Pássaros” (The Birds) in the past.

Uirapuru is a show that celebrates the guardians of birds – people that care for and maintain the traditions of the June birds. They are only found in the Amazon. The guardians are more like the carnivalescos [choreographers/artists/designers] of the samba schools. [They reinterpret and keep traditions alive]. This practice is also what I did with Chegança do Almirante do Negro (Arrival of the Black Admiral)show in Pequena Africa. [Known as Pequena Africa or Little Africa, Rio de Janeiro, it is the name for the neighborhood and the former slave port region of the city where the Company also performs]. My interest here was to connect to what is called, the cheganças (arrivals). ⁶These are popular festivals that existed along the entire coast of Brazil, traditions that are now extinct, but in the 1950s, 60s, even up until the 1980s there were still many people doing them.

Marília

Festivals that can last 8, 12, 18 hours!

Lígia

Yes! What I did with Uirapuru and Chegança and with the Saga de São Jorge, which also draws from folkloric traditions, in this case the Guerreiro de Alagoas (Warrior of Alagoas), is to to recover stories and create shows intertwining different Brazilian cultural traditions. The show Chegança is a maritime epic. We went to Arembepe, Sergipe and Bahia to do research. We learned from master practitioners, many of whom have already died, traditions such as the beat of the tambourines, that we included in the show.

That was when we had money. When there was decent support from the Ministry of Culture, during [President] Lula’s first term [2002-2005], which was fantastic, when we were able to do research in person and develop shows in the best way possible.

Guilherme

Yes, Lula’s first term with Gilberto Gil as Minister of Culture was something special. What did he call this support for culture?

Lígia

“Cultura viva” (living culture). Then the program of “cultural points” [small organizations or cultural centers] all over the country was started.⁷

Guilherme

When I was in New York before I came back here, I participated in a group established in 1989 by the New York university professor, David Ecker, called Living Traditions in Art. The group focused on “cultural-aesthetic navigation” in different traditions. It became an international association celebrating living traditions and the material and immaterial heritages of “living” people who are the true books. Gilberto Gil’s program was similar. It was very important. Today we recognize how much the meaning of “the future is ancestral”⁸ is completely resonant with these transtemporal and transcultural visions and traditions. Without a doubt, the trajectory of the Companhia de Mysterios e Novidades is a project of living traditions in art.

Jessica

Perhaps now might be a good time to tie in this discussion of the procession with the “second act” of the interview, that is the history of the Company. How does the history of the procession tie in within the history of the Company?

Guilherme

What we are doing is almost an archaeology of creation or a genealogy. The discussion on the procession has already given us a good picture. So I am curious to see how your journey evolved, moving from the time of the Grupo Coringa in the 1970s, where you were gathering experiences like cotton candy to your life in Europe, and then to returning to Brazil and how these elements took shape as the Companhia de Mystérios e Novidades.

Lígia

So for the “second act” of the interview I’ll continue to talk about the procession, weaving in some of the things that influenced it. When I left Grupo Coringa, which was really my school, I broke a little with my life here in Rio de Janeiro. I graduated from Parque Lage, the School of Visual Arts that Rubens Gerchman created during the dictatorship. This was where I met Graciela Figueróa. Young people went there but there were also people of all ages. Maybe I was the youngest. I was 16 or 17, but my friends were already 21, others 22, some in college and others studying other things. You know? There was a mix, us younger students, older ones, artists, lots of different people who took courses with Hélio Eichbauer, who was a revolutionary. That was my school. This is what educated me, not that we are ever done with that, but this is what formed my outlook, brought me to the world that I still work in today. It triggered something deep inside me and lit my imagination to seek within myself, to work with art, woke me up to make art.

So, Parque Lage and Hélio, as well as Graciela and others that I met at the time, are the people who taught me how to work and brought me into this world, but completely outside of any formal education. I didn’t go to college. I realized that at that time I was thinking about going to study at the School of Fine Arts. But even prior to that I was about to go and study agronomy. I was going to take the entrance exam for agronomy, because I wanted to live away from my mother and father. I wanted to live alone, live my life, and at the time I had the possibility of studying in the countryside and I loved this idea. I wanted to study there and I already had a boyfriend who wanted to do the same. So, we wanted to go there but suddenly everything changed because I met Hélio Eichbauer and I started taking classes with Roberto Magalhães.

I had won a scholarship to take art classes when I was 13. Going back a bit further. My uncle Carlos Veiga was an artist and he had many connections with artists. He also painted, drew and was friends with Ivan Serpa. So, when I was 13, I took classes and won a scholarship to do an oil painting course, which I didn’t know anything about but I learned how to paint with oil and other materials at Museum of Modern Art (MAM), Rio de Janeiro. I was the only child aged 13. The rest were older people who were already artists. So, I discovered Parque Lage, School of Visual Arts, not through my uncle Carlinhos, but through Roberto Magalhães who was teaching there. I started taking classes with him and music classes with [the composer] Vera Terra. I love her. She was young too. She must have been 22 and I was 17. I also had several other teachers there too, Celeida Tostes … Only the best!

So, I gave up on going to college. I tore up the entrance exam because I knew I was going to get in, so I tore it up. I didn’t go to Rural [University] and I didn’t go to the School of Fine Arts but to Parque Lage. There I made friends, friends that I have to this day, some are gone but everyone accompanied me on this path of creating the Company.

I’m saying this because, when I left Rio de Janeiro and decided to go live in São Paulo, I wasn’t planning to create a company. I was just walking in the direction of the things I wanted to do. I really wanted to work with street theater. I already had that in my head. It had to do with things I found in the Unesco Courier magazine I mentioned, with what I thought, and what I was doing with Graciela in Coringa. Because in Coringa we did a lot of things on the street too. There was this amplitude, always a possibility of doing things on the street. Although it wasn’t a dance thing and didn’t have much to do with theater, I got into theater later, it was nevertheless something that, let’s say, didn’t have a segmented mindset about music, dance, and theater, definitely not.

Marilia

True, Coringa didn’t have that, but in a certain way it did. There were planned scenes.

Ligia

Yes, it was contemporary dance.

Anyway, when I went to São Paulo and started to think about what I would do, I started to think that I was doing both theater and dance. I had a partner who was a dancer, who had also danced in Coringa, but she was from São Paulo. I went to live there and started to teach and also attend [choreographer/dancer] Klaus Vianna’s classes and make connections with artists from different segments, from visual arts, music, dance. There we started to put everything together and I created the Grande Companhia Brasileira de Mystérios e Novidades in 1981. At that time, the company was a theater and dance company. I started to work with theater and dance and the parades and processions began to happen. They started to happen because we were working in alternative theaters and spaces at that time. The parades and processions started as a way to draw publics into these alternative spaces. The Company began to take on this characteristic of bringing together musicians, dancers, and actors and we started to work toward making an amalgam of things. We were mixing everything. Everyone did everything. The Company was born from this. So, the processions emerged naturally as a way to move things along and as a means to do something on the street. Of course, at that time, in 1981, we were also working as a dance company, our focus more than anything else was contemporary dance. We received a lot of criticism, but there was also one dance critic, Helena Katz, who gave us a lot of support.

At that time, contemporary dance was at its peak in São Paulo and Rio. Graciela had set that off. So, we were at the height of it all, doing something that no one else in São Paulo had been doing until then, making connections with musicians, who in other shows would just sit or be rooted in fixed positions. Here, it was as if they had no body. Now [in our performances] they began to have a body. People who started working with me had to be aware of their bodies and to be able to move. They began to have a body. Because working with the Company meant you had to have a body.

Guilherme

Interesting that you are using this expression “they began to have a body.”

Lígia

Because musicians had no body. They sat down to play and even today there are many musicians who have no body.

Marilia

It’s amazing how someone can play beautifully, yet have no body.

Ligia

They don’t know how to move.

Guilherme

They have to develop muscles so that they can make others dance.

Lígia

That’s it! But it’s changed a lot, but back then, it was a complicated time because everything was still very fragmented.

Marília

Graciela’s dance performances were criticized a lot. It was either total passion or full-on criticism. For many critics what she did was not dance. Firstly, she danced with people who had no dance training whatsoever.

Lígia

Yes, but there were also trained dancers, super ballet dancers.

Jessica

It might be interesting to highlight some of these initial processions to follow the thread of this connection with the genealogy of the Company. Was there a moment when it all started to come together somehow? Are there any examples you can think of?

Guilherme

When did the idea of procession emerge? You said just now that it started as a passageway. The procession was a passing between one place and another, between the alternative space or theater and the street. So, what happened for this to become a procession? Because the procession already has a historical, folkloric or spiritual layer, so this mix is not just contemporary dance. I don’t know, but maybe this goes beyond Graciela?

Lígia

I just remembered something. When John Lennon died it was the first day of a short season of performances of Grupo Coringa at Parque Lage. It was to be held on a temporary dance floor set up around the pool. We heard the news of Lennon’s assassination in the morning and we were going to debut that night. There wasn’t even a phone, I had gone downstairs to talk to Isabela on the pay phone and Isabela told me that John Lennon had been killed. So, I ran upstairs to Graciela and said: “Graça, John Lennon was murdered.” She said: “Let’s have a procession. Let’s sing ‘All we are saying is give peace a chance.’ We will enter Parque Lage and carry Regina Vaz above our heads.” Regina was thin, the lightest of all of us. So, we started the performance, entering in a procession, carrying Regina Vaz to the place where the stage was built behind the pool. There was a small platform that they made to make dancing easier because it was a stone floor. It was awesome. That procession is very symbolic to me. That’s a good example. There we were learning how to do processions.

When I started working in São Paulo, we didn’t perform on the streets, but in theaters and alternative spaces. We would get involved in some projects at the Maria Della Costa Theater. We would come up with a show that would bring together people from theater, dance, and music, and together we would put on a show in two weeks, staging and performing it. We also did a contemporary dance festival at the São Pedro Theater. It’s a wonderful theater now, but at that time it had a lot of problems and had been abandoned for a while. We did a lot for that theater and performed a thousand things there! We did processions and parades outside as a way to attract the public. We opened Sesc Pompeia and other Sescs [Social Commercial Centers – arts, culture, sports and entertainment centers) that were part of the beginning of a public policy directed by Danilo [Santos de Miranda, cultural manager and director of Sesc from 1984 until his death in 2023].⁹ We opened Sesc Consolação, Sesc Pompeia, Sesc Anchieta, among others. The Company would enter in a procession. At Sesc Pompeia, we entered in a procession to get to the theater. It was a way of bringing people together, joining the street with the theater. Even though the theaters were free, they were nevertheless always inside closed spaces. So, we wanted to build this bridge between the street, between the public and the private, and the procession was the way we found to do that.

Guilherme

A way of bringing people into a poetic state. So, like this you have no audience.

Lígia

No, we don’t have an audience of spectators that sit and watch, you are with the actors, musicians and dancers.

Guilherme

It’s a learning experience, accompanying you all on these processions, we see everyone smiling. It’s like being on an enchanting cloud…

Marília

You’re in on the action. It’s interesting! You are not passive. You are not watching.

Guilherme

You have to walk because the narrative is moving.

Ligia

You are part of creating a state of procession.

Guilherme

State of procession, yes! Today a student said: “the state of performance.” I complemented that with describing a poetic state. So, we have a poetic state, a state of performance, and now, a state of procession.

Marília

It’s so strong, moving out from the place of being an audience who watches.

Jessica

This reminds me of a Canadian artist, Paterson Ewen, who made woodcuts – the printing technique that consists of engraving an image in wood and using it as a matrix to reproduce an image. The wood here is a support, something that is used to make something else. But suddenly he realized that what he was doing with the wood was more interesting and started working on top of the wood. I find it fascinating that these processions began as a call to the public to come to a spectacle. Do you remember the moment when you realized that the procession was no longer a way to bring people to a spectacle but actually the spectacle itself?

Lígia

So, about 2000 there was a turning point. I had left São Paulo, but when I arrived back in Rio de Janeiro, I didn’t have a place to work. I didn’t have a group. My group was in São Paulo. When I left, the Company was doing well. People said: “You’re crazy. You have a lot of work here. The Company is very respected. You’re called to direct things.”

Guilherme

Was Graciela Figueroa also in São Paulo at that time?

Lígia

No, she had already gone to Uruguay.

Marília

Lígia left Grupo Coringa for São Paulo in the early 1980s, but Graciela stayed.

Lígia

The group ended in 1984. When I was leaving, the group was already falling apart.

Guilherme

Coringa’s story is from when to when?

Lígia

From 1976 to 1982 or 83. We also went to Uruguay and did things there. So, when I got here to Rio, I needed to start over. I started teaching and bringing people together to do things and wondering what I was going to do. How am I going to bring my group from there to here? We did a season of the Saga São Jorge (Saint George’s Saga). This was one of the first shows we did on the street that we did that will always be a reference for us. We started that in 1994. This show will be part of our repertoire, I think, to the end of our lives!

The company had performed a season at the Museu da República (Museum of the Republic) and I had started teaching there. Then I began to think about what I wanted to do and it came to me. My idea was to hold an All Saints’ Day procession for peace on November 1st. At the time, no one celebrated November 1st. Everyone celebrated All Souls’ Day and the day of I don’t know what, Saint Sebastian’s Day, for example, but no one celebrated All Saints’ Day. I thought this All Saints’ Day thing was incredible.

Guilherme

You spoke about All Saints Day for peace. Did you already incorporate in the processions the Banner of Peace?¹⁰

Ligia

No. Not then.

Guilherme

Is this 2000?

Lígia

It was in 1999. The first procession of Todos os santos pela paz (All Saints Day for Peace) left from Largo de São Francisco, where we had started working in the arts and cultural space run by Miguel Saad. We left in procession towards Praça XV, from the Church of São Francisco de Paula to Praça XV. We did this, let’s see, from 1999 until 2007. There we were establishing a relationship between the city and the procession.

Guilherme

That’s it!

Marília

Yes!

Lígia

That’s how we began doing processions. After this, we started to put on shows in São Francisco de Paula square, working in that space, and bringing people together. We brought some people from the Company in São Paulo to do work here. We started to get grants to produce shows and we put on several shows. We always did them in the square. I worked with [the composer] Tato [Taborda] there and Geralda [the name of the instrument that Taborda created]. We did several shows in that square. We did the first performance of Dia fora do tempo [Day Out of Time] there. The music was all played by Geralda, that is Tato and Geralda. That work was incredible. It was the first time we worked together. I had worked together on something and then he invited me to work with him and Geralda. We went to PercPan [World Percussion Panorama festival dedicated to percussion instruments that takes place annually in Salvador, an event that mixes rhythms and traditions]. Gilberto Gil was there lying in the wings listening to Tato play Geralda and I played an ocarina and did some stuff with wind instruments. After PercPan we did it here in Rio at the João Caetano Theater. Then Tato invited us to do Dia fora do tempo at that festival, what is that festival called? I don’t remember the name but anyway, we also did it in our square, and in that square in Arpoador, that was amazing.

Guilherme

Was that at Circo Voador [a concert arena in Rio]? When it was at Arpoador [Ipanema Beach]?

Marília

The arena was right on the seafront and the stage was inside.

Lígia

We did Chegança there outside as a procession until we got inside.

Marília

You know that really the procession as the sole focus only occurs in the Todos os santos procession, the other shows have processions, but they are part of the show.

Lígia

That’s where the processions began. Of course, the Saga of Saint George hadalready been performed in São Paulo. It premiered in São Paulo. We were already doing a procession of Saint George as a way to start and move toward telling the story of Saint George. We would start with a big procession and end at a specific locale. For example, we did it at Pátio do Colégio in São Paulo. We premiered the show at Sesc in São Paulo at Pátio do Colégio with the São Jorge procession with everything we wanted to do, with a canopy, Our Lady, São Jorge, Banda da Lua, everything! We left in a procession from one place to arrive at Pátio do Colégio. Then everyone would gather and form a big circle and we would start telling the story of Saint George. We have also performed the Saga in various countries around the world: Italy, Germany, Romania and also Columbia.

Jessica

Performing in Praça Harmonia (Harmony Square) and the Company’s home base when did that start?

Lígia

Are you talking about Gamboa? Well, it was in 2007. We started our practice of doing processions in São Paulo, but it wasn’t as strong as when we came to Rio. Although I did a lot of things on the streets there, São Paulo is not really a street city like Rio de Janeiro. But also, there came a time when there was a big shift in my life. A great friend who worked with the Company died. It was a shock for me, I had to leave São Paulo. I didn’t want to live there anymore. It broke a bond between me and the city. So, despite having all the financial and economic conditions to stay there, a much easier life there than in Rio, and having achieved a very good artistic place for the Company, the bond with São Paulo had been broken. I was also working a lot for closed spaces, like Sesc, on commissioned projects and I wanted to have more freedom to experiment things on the street that I wasn’t having at the time. Also, I had personal issues, an anguish, and a desire to break that situation and start all over again. I thought that Rio de Janeiro was potentially a street place, but, in fact, first of all, I had wanted to go to Recife because my director who I worked for, Romero de Andrade Lima, was in Recife. He had also left São Paulo and returned to Recife. So, I had the opportunity to work with him there. I had this invitation. But then I met Marília, and then I said that I won’t be able to go to Recife, and I’m going to have to come live here. So, I came back to Rio de Janeiro.

Jessica

So did you meet in São Paulo? Or did you meet in Rio later?

Marília

We actually had met before in Rio, at the time of the Grupo Coringa, but when I started with the group, Lígia was already on her way to São Paulo. So, we knew each other, but it was at a Rio Aberto meeting in 1996 in Mexico that we got together.¹¹ I had just separated and Lígia had just lost this friend and separated too.

Lígia

I was at rock bottom.

Marília

So we met at Rio Aberto in Mexico. It was one of the first international meetings of Rio Aberto. I went to get over my separation and meet my master-teacher Graciela Figueroa.

Lígia

So there was I, not for nothing. After the death of my friend, I had never felt so bad and I wanted to be comforted.

Marília

And I had finally managed to separate.

Lígia

Marília was in that state and I was in the state of wanting to be held. I went to be held by my master-teachers Maria Adela and Graciela Figueroa and my sister [in spirit] Joeritha Jones. I went to stay with them. I was devastated. That’s where we met. We came back from Mexico together in 1996. Then I went back to São Paulo and we started dating and I said: “I think I’m going to have to move to Rio de Janeiro.” So, I decided to go back to Rio. This was in between 1999 to 2000. On returning, going back to what we were talking about, I think the issue of the street became solidified, more than ever. Because there was a need to go back to the street with the processions and strengthen this.

When I left Rio de Janeiro in 1981, I had left a Rio de Janeiro that was completely tied down by [the TV Network] Globo. I had just come back from my experiences in Europe with Teatro Pirata, which had made me want to experiment and seek out other things. I had some friends who worked at Globo and they said: “you can come and work at Globo, I can recommend you.” But I didn’t want to work at Globo at all, I hated it. What was happening here in Rio at the time was only Globo. Now it’s nothing, but back then, either you worked at Globo, or what you did was useless, except for crazy things like Coringa, that were totally against the grain.

Jessica

Can you – because we will need to move on to the third act of the interview – talk a bit about one procession? I don’t know if that’s possible? A particular aspect maybe or specific elements?

Lígia

The procession of Todos os santos (All Saints) because it features the procession of all the saints. The other shows begin with a procession, but the procession is not the focus. The focus is rather the narrative of that particular presentation or show. The parade gives a special touch, it starts and finishes the show.

Marília

The parade with everyone together is the procession.

Guilherme

It’s interesting the use of both words. When do you use the word “procession” and when do you use the word “parade”?

Lígia

I will say that the Todos os santos procession is perhaps the most significant procession of the Company. Other processions came later, but the first and most significant procession is Todos os santos pela paz (All Saints for Peace). It was very significant because after we started it, in the second year we received the Banner of Peace honoring the action of peace that the procession embraced. So, we started using the Banner in all of our processions, but it became a special feature in the Todos os santos procession.

Guilherme

Just to draw attention to this question of parade and procession. Because I think it gains a symbolic dimension. It stands out in the face of criticism of contemporary dance, in the face of criticism of public art. It is something else, without precedent, because it mixes these things. I think it’s incredible, it’s a nomadic sculpture. It’s enchanting, it pulls all the saints together at a moment when the fight between the saints is very big.

Lígia

Yes absolutely. It is an artistic ecumenical procession. It is a mix of the sacred and profane and has its own aesthetics, despite being in the tradition of processions with all the attributes of a procession: special standards and banners, saints, songs…

Guilherme

It is interesting to think about the sacred-profane confluence. The philosopher Agamben speaks of the separation and difference between the sacred and the profane. Hearing you talk about the origin of the Company’s processions points to the search for a profane relationship with the street, breaking with the closed (sacred) space of the theater. Here, the worlds of the sacred and the profane merge through public art. The sacred requires a closed, restricted space, and the profane is open for society. The sacred is a secluded and private experience for the few, which refers not only to the closed theater, but also to all institutions of the visual arts and hence, the impulse to rupture all this into public art. The parade-procession highlights this subversion of the orders, between what is inside the theater, galleries, and museums, and the life that is outside on the street. Once again, the sense of public art that the Company has built throughout its trajectory performs this game of rupture of categories and dualities: between the banal and the exceptional, the popular and the erudite, the sacred and the profane. When the enchanting procession passes by it transfigures the banal-functional routine of the accelerated life of the city on the ground. In a kind of magnetizing sculpture of multiple bodies and voices, it slows down and suspends time. Dancing and singing for all beliefs, saints, heroes, and Marys, it embodies all the fabulous power of the ancestral and future imaginations of humanity. The extraordinary meets the everyday, which becomes a sacred phenomenon.

Jessica

Yes! I would just like to go back for a moment and hear from Marília about these parade-processions!

Marília

The parade-procession yes! I think it’s the aspect of being a parade that gives it its strength, the element of procession comes from the adhesion of those participating. The shows have parades, but often it’s a parade that the actors do as part of the show, there’s no audience that joins in, there’s no adherence from the audience.

Guilherme

Strength and adherence, yes, this is like the song where tomorrow comes from yesterday!

But let me go back and ask Lígia about the Banner of Peace. So, you received it as a recognition?

Lígia

Yes! The Foundation for Peace in Argentina gave out Peace Banners based on actions carried out in the name of peace. I learned about the banner from Maria Adela, my master-teacher and leader of Rio Aberto, also based in Buenos Aires. So, I applied and wrote about our work, and we received this recognition and I went to Argentina and received the Banner of Peace.

Jessica

There’s such rich material here. There’s a lot to talk about but maybe we might start the third act of our interview and talk a little about important influences on the Company practice. You have already mentioned some, but I think it’s good to make them explicit. There is Hélio Eichbauer, Rio Aberto, Graciela Figueroa and Grupo Coringa, there are the popular traditions of Brazilian art and culture, as well as other influences. So, I think we can touch on some of these and how they contributed to the Company’s practice. Perhaps Marília, you could start by talking a little about Rio Aberto.

Marília

Great! Yes, it’s good to think about that, especially because there will be a large international Rio Aberto meeting in Rio in November 2025. After Maria Adela died the group disbanded in Argentina. So, there will no longer be a base or center there, where it all began. It will not exist anymore. So there are a lot of big changes coming. So, one of my questions about Rio Aberto is what lingers? If everything is spread, what of this system of psychocorporeal experiences lingers for those who have experienced it and those that have taught these practices? Which is a bit of this question you are asking. I came to Rio Aberto because of Graciela, because of dance, because of this kind of dance.

Jessica

What exactly is Rio Aberto? Is it a movement? A school?

Marília

Rio Aberto is a school that sees the body as the main axis of life. It is for, with, and through the body that we access our personal issues. They also use an expression they call the transpersonality of things, in the sense that we do not experience things that are so different from one another. So, what is personal is in fact transpersonal. So, Rio Aberto calls itself a school of human development. Over the years, there have been several changes but I will describe it as a school of human development through psychocorporal techniques. There is a very well-defined axis of work, on essence and personality, on the spirituality of the body, along with other things. There is this emphasis on the body and understanding that it is through experience that we change and learn. All the training is very much based on experimentation. Theory is what can be deduced from experience. So, Maria Adele’s book took years to be written because everything was based on experience. It is in this sense that we emphasize theory based on experience. So, we invert: it is not experience based on theory, because that way we lose the freedom of experimentation and its potential strength. Before starting something, we often have a notion of where we want to go. This pre-determination can actually prevent experimentation. So, that’s what we work on. Many of the themes we explore are themes of the world, tensions of opposites, all the issues of the psyche, but through the body.

Jessica

Within this, can you identify any practices that you have brought to the Company?

Marília

From my experience and my participation in the Company, it is this perception of the body as something that is always in formation. It is like supporting a body, a body I cannot say is free, because being entirely free is a little difficult, but to be more genuine, more unique. When I saw Graciela dancing, the thing that stayed with me was this: “I can be who I am.” Many years later I found a card with a photo and I had written this on the back. So, that’s what I understood then and it also has to do with a way of working the body, with a way of experiencing the body.

Ligia

Of freedom too.

Marília

Yes. To be who you are, then from the body you can dismantle these structures that are so imposed, because all the impositions, even social ones, come to the body.

Jessica

This could be a kind of mantra for the company: I can be who I am. How beautiful!

Marília

Yes, it’s very beautiful, because I was 17 years old.

Guilherme

But did you see Graciela at that moment?

Marília

Yes. She went to give a workshop in Belo Horizonte and at the time I was taking a dance class at a dance school there, Transforma. This school has to do with Marilene Martins who was a good friend of [choreographer/dancer] Angel Vianna and Graciela had a whole history with Angel. The director of this school invited Graciela to do some work with the group Transforma, so she gave this workshop which I did. I was completely shocked, number one, because she didn’t speak, it was all playing and singing, I was completely enchanted. She put on a show there with her group. I couldn’t think about anything else. She was doing what I was talking about earlier, this mix of dance and theater. In 1978 this didn’t exist: in the middle of a choreography, everyone stops in a line and [performs elements of the] Last Supper accompanied by the sound of dripping water. The music is a dripping faucet. It’s something that surprises you in such a wonderful way.

Guilherme

A question that I’ve been thinking about, especially since reading Maria Adela’s book and also taking some of her classes, is how do you bring these practices into this school without walls that is the Company? How do you bring this to the group of performers? Maria Adela’s book goes deep into all the studies of the body, also of chakras. So, when you say that for a person to get up on stilts they need to enter this state of mindfulness, I wonder if there is a bridge to be made to the practical training of the performers with the Rio Aberto school.

Marília

Yes, I think there’s a lot of connections. In some productions or before shows, the idea of body preparation has not so much to do with physical preparation, although it is that too, but with a more expanded and holistic sense of the body. This possibility of aligning the centers, perceiving oneself as a body of energy, as having a body that generates and radiates energy.

Guilherme

“Having a body.” I love that.

Marília

Yes, and from a place where there is no judgment, the work is about energy and energy has no morality, no judgment, the body has no judgment. There is no right and wrong. In the sense of not this or not that. The body is who we are, what we are made of. It is movement, until death. Now the body is ready, there are times when it is ready and times it is not, it never stops. What can a body be? A body that responds to life, lives life, cries, laughs, opens up, shuts down, goes out, plays, moves, not a body as a pre-defined thing. It is the body that is here. It is presence – a body that can be present.

Jessica

It is fascinating how this state of “presentness” is fundamental to the procession and the performers on the stilts. Since we began the interview, you have both been emphasizing this state of presence. Perhaps we can link this to something that Lígia said at the very beginning of the interview about the procession, quoting an expression by Hélio Eichbauer, as “precise daydreaming”. Maybe it’s time to talk about Hélio.

Lígia

Yes. It is because, in fact, everything is very connected. Things do not follow a linear timeline. Despite speaking within a certain chronology here, all of this is happening in a kind of timeless time. The things that contributed to and gave a body to the Company are totally intertwined. Hélio, Graciela, Maria Adela, and everything we learned from them – I’m talking about these three master-teachers and how they shaped our performance as a Company. When the group was formed, everything was in this spiral. These are layers of learning that were there from the beginning of our existence as a collective, as a group. These were present back in 1981 when I went to São Paulo. It was an education in the broadest, deepest sense of the word educate, to be and to receive teachings from these masters who are completely connected. Graciela met Hélio through us. We took Graciela to Hélio’s classes and Hélio began to work with Graciela. The first show that Graciela did in Brazil that had scenery and costumes was designed by Hélio. At that time, he had already created theatrical scenography for Zé Celso and Martim Gonçalves, and taught courses at MAM [Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro] and EBA [School of Fine Arts] before Parque Lage. Just look at the connections. Maria Adela came to Rio de Janeiro through a member of Grupo Coringa and then met Graciela and the group. Me, Joeritha [Jones] and the whole group did the first Rio Aberto training, although it was not formal at the time. Maria Adela came to Rio and we went to Buenos Aires to work with her. We started to develop the work of Rio Aberto in Rio de Janeiro with those people who worked with Hélio, Graciela, and Coringa. Do you understand how everything is totally connected? It is a cosmic embroidery. So, when Marília joined the Company, it is as if she had been there for a long time and she came in to give the final touch – the end of the embroidery and the beginning of another cycle. That is, to bring in a way, I won’t say systematized, because it isn’t, but in a way that is more structured, the Rio Aberto system further within the Company, as a continuous body practice, which I had been doing before but in a more chaotic way…

Marília

It continues to be chaotic but bringing…

Lígia

…something else, an additional quality. Musicians who worked with us, who are now multi-artists, who have groups, who work with other things, who make popular operas like us, they are from that time when we stirred the pot, mixed all of this up and performed. Do you see what I mean? So, these things are all intertwined. It’s not linear. Tomorrow comes from yesterday and yesterday will still come. What appeared at that moment was already there before, but someone pointed it out right there at the moment.

Jessica

Graciela and Maria Adela bring to your practice the body and a search for authentic corporal experiences that seems very strong to me, together with this possibility of catalyzing a genuine identification, as you said Marília, a moment of feeling and recognizing something that “I can be who I am.” So, what was Hélio’s power? Thinking about the Company’s practices, what did Hélio bring? What is this “daydreaming”? What is this “precision”?

Lígia

I think that Hélio somehow brings…I was going to say that Hélio is more Apollinian than Graciela, but he was also very Dionysian. But let’s say that Graciela went for a catharsis, a more Dionysian process, foregrounding the body and corporal expression. She strove to promote and provoke a heart pulsing with enthusiasm, with Dionysian energy and everything that causes a volcano in all of us. I’m talking about energies that come together. Hélio, in a slightly more Apollonian way, perhaps, intertwines this with a study of these corporal practices. His classes at Parque Lage were fantastic. Hélio’s course first was called Body Workshop and then Pluridimensional Workshop. He didn’t teach art theory, he taught art, that is art in its most expansive sense and possibilities. We performed every day. Let’s call it a performance. We set up shows. We studied Shakespeare. When we prepared for the production of the show A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Parque Lage we slept there.

We had classes with Hélio three times a week. It was the most wonderful of things. Three times a week and we went crazy inside Parque Lage. We did everything! We danced, took dips in the pool, and acted out scenes. We did a show about Isadora Duncan and Hélio invited the audience to come. The students were crazy, of all ages and from all over the world, all with different experiences putting on a show about Isadora Duncan!

One of the beautiful things Hélio created was the “spectacle conference”– a term he created. He did somersaults, inverting and inventing terminologies and art forms. But on top of that, it was very practical. We thought about things, lived things, imagined things, painted, characterized, studied. During the week, for example, we studied what we were going to do for a spectacle conference about the work of Paul Klee. So we created a spectacle conference about Paul Klee. It was a holistic learning of everything that was possible about art.

Marília

Scenography was key to Hélio’s practice, starting with working with his master …

Lígia

Yes, the set designer Czech Josef Svoboda. But actually, at that moment in Parque Lage, it was something else, it was the Body Workshop, and then its pluridimensionality. So, the focus was on the body. It was based on body work.

Marília

Can I just say one thing? Maybe it was working with the body, involving the body [but] it is not body work. Graciela does body work – it is of the body. I’m trying to differentiate the two. It is rather a learning of the body, of oneself through the body, through dance.

Guilherme

I remember the exhibition at Parque Lage, Jardim da oposição (The Garden of Opposition) about the School of Visual Arts when Gerchman was director in the late 70s. Part of the exhibition featured Hélio Eichbauer’s courses. What you are saying about this work with the body makes sense; it was an improvisation. Everyone in the trees! It is not an isolated body. It is the body with.

Ligia

That’s what I’m talking about. Hélio saw teaching and learning as reciprocal drawing from his experience with Svoboda and scenography.

Guilherme

Jessica and I attended some of Hélio’s classes at Parque Lage in 2014 and I even talked to him about projects at MAC [Niterói Museum of Contemporary Art]. Because what really stood out for me, something you haven’t mentioned yet, but perhaps I can bring up here now, was that he was very connected to sacred geometry and Rudolf Steiner.

Lígia

Yes, also.

Guilherme

He was familiar with Steiner, I mean, he had connections with Eastern Europe too.

Lígia

Yes, because he was an apprentice of Svoboda and he brought back this knowledge of scenography to Brazil. But he never, absolutely never, restricted his classes to only working with scenography.

Marilia

Graciela’s dances were also related to everything.

Guilherme

What’s interesting is that you take a middle path between Graciela and Hélio, between the two of them. The middle path? A little of each, not exclusively of one or the other, but of the two, a synthesis, a chemistry in between.

Jessica

I think it is a process of aggregating, resisting, generating another political and affective energy, something that is greater than the sum of its parts, a kind of composing …

Guilherme

…a composition. Because there are scenes in the processions where there is a scenography. For example, when we did the procession of Nossa Senhora de Saúde (Our Lady of Health) when we were leaving Praça Harmony square, there was a ceremony at the crossroads before heading to the church. It was a street theater-performance, there was a score, a scenography. The procession stopped or rather gained another symbolic dimension at the crossroads. You bring together what becomes no longer just dance, just theater, and not even performance, in a single public art scenography – using stilts and the legacy of Hélio Eichbauer and Graciela Figueroa. You embody, very well, the symbolism of the beating hearts, bodies and grounds at the crossroads.

Lígia

This crossroads is the place of strength. I think that if we were to synthesize our work, it would be at this crossroads. This intersection between masters. Although, we will also talk about Maria Adela, Hélio Eichbauer, and Graciela Figueroa as a triad. It is not a duo. It is not a pair of opposites. It is not a duality. None of that, but it is a triad, one thing is inside the other.

I’d like to talk a little more about Hélio because, I think, it might be more difficult to talk about his influence on our practice. Maria Adela created a system of movement that became a school. Graciela too, was also a school in the sense that she impacted whoever worked with her. Hélio, however, is more of a kaleidoscopic vision of everything. He gave a dimension of art as art history, without being an art professor, in the strict sense. He shared with us his experience and knowledge and made us experience and practice it. He had a lot of knowledge. He was an incredibly knowledgeable and wise person. He was an intellectual indeed, but in a spiritual sense. He wasn’t really from that Parque Lage era in the 70s. He did a cosmic somersault on all that. He had something beyond that time. Even with all the openness that Parque Lage embraced then he was doing something very different from everyone else. You can also see this in his notebooks and drawings. That’s one thing I share with him: a passion for notebooks and sketching ideas.

Guilherme

We have to publish and disseminate your notebooks! Interesting because at the time, the options for schools and artistic training in Rio were very limited, so even in Parque Lage, it was necessary to break with a colonized vision of art. Experimentalisms need outlets, you left and Hélio too, as well as many other artists and thinkers, finding that they were able to expand, to be influenced by experiences and values outside the limited history of art.

Lígia

Hélio talked about everything at that time. He talked about Africa, he talked about indigenous people, he talked about all the things shaping our education. It was a special era at that time in Parque Lage, we worked on various intersecting planes of art, science and spirituality. It was poetry, a beautiful thing. We studied artists who did amazing things: Europeans, Africans, Indigenous people, North Americans. He had a passion. It was not so much an intellectual knowledge, but a knowledge as an artist, not as a teacher.

Guilherme

He was a teacher, an artist teacher. He is the one who makes the experience of knowledge an ethical-aesthetic instrument of donation. That is what you do …

Ligia

You do as well. It’s something that goes beyond that. It’s a universal donation.

Jessica

Dearests, we know that this conversation is never-ending, but in order to publish we are going to need to finalize. Maybe we can wrap up with this idea of teaching beyond? I think it’s a nice way to point toward a continuation. There’s still a lot to talk about! That’s why I made this suggestion of three acts.

Guilherme

Yes, what we mentioned today are just tips of the iceberg. A spiral conversation begins: review, revisit, restart…

Marília

It’s also really great as it inspires us to recall and recover things.

Lígia

Recover, yes, but I also feel that there is still a lot to say in this third act. We’ve just started digging …

Guilherme

One question, you mention the triad of influences: Maria Adela, Graciela Figueroa and Hélio Eichbauer. But there is also an important individual who is Amir Haddad. Another artist outside the box.

Lígia

Yes, of course, but he came along more recently in our history. His work in the theater and public art is revolutionary. But the encounter with him happened later. That’s why I highlighted these three masters, let’s call them founders. We’ve also had a number of wonderful people who collaborated with the Company’s work in an important way. For example, Ludovico [Muratori] and Romero [de Andrade Lima]. Anyone who knows Romero knows the influence he has had on my work. Another reference I didn’t talk about either.

I only really got in touch with Amir when I returned to Rio de Janeiro in the late 1990s. Before that he was following his own path and I was following mine. So, he is not my master-teacher like Graciela, Maria Adela or Hélio. These people are master-teachers of my youth. Of youth and maturity as well. But Amir already had a body of work totally different from mine. We have shared experiences and have also worked together. I have learned a lot from him, but he is not my master-teacher in this sense of shaping my work.

Guilherme

I think you share an ethic.

Lígia

It’s interesting, I spent ten or twelve years without meeting Hélio, but he was still a complete part of my life. When I returned to Rio de Janeiro in the late 1990s, he had also returned to teaching. He hadn’t been teaching all that time. So, we met and then I made him a proposal. I invited him to work in the street with me which he had never done. So, he started to be my art director. I’m saying this because it’s a completely different curve from Amir. For example, Amir, I met him when our work already had a public face and we already had an established way of doing things.

Marília

It’s an absolutely different aesthetic.

Lígia

We don’t have an aesthetic affinity. Our affinity is rather for public, political art.

Guilherme

So you invited Hélio Eichbauer to work as director of scenography for the Companhia de Mystérios e Novidades?

Lígia

Yes, we called him our art director. He was the art director for Ciclope. He worked with us on this show and it was incredible. When I returned to Rio de Janeiro and we met again and started taking his classes, he got to know our space. That must have been in 2000. He participated in two or three shows and was the art director for two plays: Cheganças and Ciclope. It was very important for us, there we had quite an upgrade!

He came to the Company not only as a teacher, mentor and collaborator, but, of course, as a professional. At the time he was writing his book. He mentions us in the book focusing on the experience of Chegança because it was a totally new experience for him. He had never done any street theater before.

Jessica

How wonderful that the apprentice came to be a teacher for her teacher!

Lígia

The apprentice spurred him into doing something he had never done before.

Guilherme

I only attended one of Hélio’s classes. I felt he was quite Apollonian, but also quite metaphysical. It’s very interesting to think about his influence on your work. There’s also something you mentioned comparing São Paulo and Rio about Rio being a street city and I can imagine extending this comparison to Eastern Europe: when he steps on the ground in Rio de Janeiro and feels the energy of the ground in Rio, this thing where when you start to stick to the city, the city starts to stick to you.

Marília

Hélio also is very Brazilian in his love for Brazil.

Ligia

And for the Brazil of these poets. He connects it to something so beautiful.

Jessica

I think we can end this beautiful conversation with this love for Brazil and the ground …

Guilherme

Because you have a party to go to and we have an opening. We must wrap up.

Lígia

The ground yes… it is body, ground, and heart. All that. It’s the three.

Jessica

Thank you very much!

***

Ligia Veiga

Actress, musician, and dancer, she was a member of the Rio de Janeiro group Coringa Grupo de Dança and performed in the Italian street theater Teatro Pirata in the 1980s. She is the founder and director of the Grande Companhia Brasileira de Mystérios e Novidades (1981). Since 2007 the Company has been situated in the port area of Rio de Janeiro and engages with the region through shows, festivals, workshops, forums, parades, and activities throughout the city’s yearlong cultural calendar. She created the Projeto Gigantes pela própria Natureza (Giant Project by Nature) – a traveling orchestra on stilts, consisting of practical and theoretical workshops that inaugurated the educational activities of the Casa de Mystérios and Praça da Harmonia.

Marilia Felippe

Marília Felippe is a performer of dance and theatre and a body educator with a degree in physical education from UFMG and in psychocorporal therapy from the Rio Abierto Foundation (School of Human Development) and trained in dance with Graciela Figueroa and Grupo Coringa. For 12 years (1988 to 2000), she directed the Coringa Rio Aberto, which was then a representative of the Rio Abierto Foundation (“para el dessarollo armonico del hombre” www.rio abierto.ar). She is a teaching instructor of the same system, which aims to contribute to human development through psychocorporal techniques where the movement of vital energy is the pillar and starting point for the development of work. For 25 years, she has been a member of the Grande Companhia Brasileira de Mystérios e Novidades, a theater and popular opera collective (www.ciademysterios.com ) and coordinates the activities of the Casa de Mystérios, a cultural facility located in the port area of Rio.

***

Karen Eppinghaus