On Asylum Archive

Vukašin Nedeljković (Visual essay) Anne Mulhall (Text)

The Covid-19 pandemic and institutional and state responses have brought the realities of the global apartheid system of the racialized border regime into stark focus. While those living in comfort within the charmed circle of material and ontological security and plenty could comply with public health measures – social distancing, frequent handwashing, working and schooling from home – without much acute difficulty or suffering, this was not the case for the majority of people. In particular, it was not and is not the case for those living in already precarious conditions and subject to state violence and abandonment. The situation of precarious migrants, particularly those seeking refuge, already living on the margins, has become much worse during the global pandemic. While multiple governments legislated for isolation and distancing, for migrant workers and for people seeking asylum the response of political and business interests was, on the contrary, to enforce a mass incarceration that writer Arundhati Roy described as “physical compression on an unthinkable scale.”1 Roy described the horror of the Indian state’s treatment of migrant workers as the country locked down: “As shops, restaurants, factories and the construction industry shut down, as the wealthy and the middle classes enclosed themselves in gated colonies, our towns and megacities began to extrude their working-class citizens — their migrant workers — like so much unwanted accrual” and those displaced “with no public transport in sight, began a long march home to their villages.” As Roy recounts, some people died, some were subjected to police violence and humiliation, made to frog jump or, in an incident that went viral globally, herded up and hosed with chemical spray. Even this avenue of flight was closed down when the government closed state borders and forced people to return to camps in the cities they were trying to escape. Across Europe, migrant workers and asylum seekers were likewise herded up and caged during the lockdown. In Greece, conditions in the densely packed camps where Europe has imprisoned people seeking refuge within its borders deteriorated even further. The EU took the opportunity that the pandemic crisis presented to further intensify its war on migrants. Covid-19 became the reason, as if the EU states need one, to close ports to search and rescue ships, as was the case in Italy. In Greece, the government suspended asylum claims entirely during the early stages of the lockdown and used the pandemic as an excuse for further confinement, abandonment and violence. As reported by the New York Times in August, since then “1,072 asylum seekers have been dropped at sea by Greek officials in at least 31 separate expulsions”, while in September fires destroyed the largest camp in Europe, Moria on Lesvos, leaving at least 13,000 people without shelter and barred from entering the nearby port town of Mytilene.2 This is the EU that the artist Vukašin Nedeljković has begun to document in his new project Fortress Europe, beginning with photographs taken in Athens and Diavata camp in Greece on the cusp of the lockdown, and in Paris and Calais in France where his work documents the violent architectures of death and violence that people seeking refuge and people without papers have to contend with.

Nedeljković’s major project, Asylum Archive, has focused its critical documentation on the asylum and deportation regime in the Republic of Ireland. Here, too, the pandemic intensified the necropolitical logic of that regime. In 1999, the Irish state instituted the system of Direct Provision and Dispersal. Under this system, people are dispersed to an accommodation centre, often in remote locations that effectively imprison people in hostels. People share rooms with several strangers, while families often are confined to one room – most often for several years while awaiting the outcome of their cases. In most centers people do not have access to cooking facilities and meals often of poor quality can be eaten only at specified times. A weekly allowance of €29.80 for children and €38.80 for adults is allocated, and out of this people have to cover all expenses that are not basic room and meals. The total ban on access to work for people seeking asylum was ended in 2017 when a former asylum seeker received a ruling in the Supreme Court that under the EU Reception and Conditions Directive, the government have to provide some form of access to the labor market. The form the government chose is restricted, however, with access given only if a person has been in the system for 9 months without a first decision on their case. Many people are excluded, particularly those who had been at the appeal stage when the legislation was enacted, while those who are eligible are often de facto excluded from decent work by the 6 month duration of the visa and by obstacles to obtaining a bank account or driving license. Access to further education is likewise highly restricted and unevenly accessible. The effects of these restricted rights and conditions are exacerbated by a legal asylum process that is broken and deeply dysfunctional. Long delays in being called even for a first interview, the lack of legal advice and representation when making an initial application and going to the interview, the lack of regulation of the crucial work of interpreters, the high rate of refusal at first decision, the lengthy and corrosive appeals process, and undergirding all of this, the deeply racist culture embedded in the Department of Justice that oversees the system all contribute to the particular corrosions and dehumanizations that people are subject to in the Irish inflection of the EU border regime. The Irish Direct Provision system aligns with the geneaology of incarceration specific to the Irish nation-state, with “problem” populations (“morally defective” women, the children of the poor, people with disabilities, mixed-race children, Traveller children) institutionalized in industrial schools, mother and baby homes, Magdalene laundries, psychiatric hospitals and other carceral institutions within the Irish state’s network of containment.3 While people are given the means to stay alive, the system works to strip them of their own selves and their future. Through the sheer force of will that some can hold on to, the system may not succeed in this but that is how the machine grinds on in its corrosive, relentless way.

While the state’s management of the Covid-19 crisis in Ireland has brought the architecture of Direct Provision into clear relief, the organizing of people in Direct Provision has also come into mainstream notice through the determined and inspiring work of MASI (the Movement of Asylum Seekers in Ireland) in particular over many years and through people courageously speaking out and collectively refusing to suffer silently the violations and humiliations they have been subject to. The first outbreak of Covid-19 in a Direct Provision center occurred in the Skellig Star Hotel in the small town of Cahirsiveen in Co. Kerry, where over 100 people were transferred from Direct Provision centers in Dublin in March 2020. Within a short time, over 20 people in the centre had contracted the virus. The response of the government, state departments as well as of the centre management was to attempt to confine people to the center while still failing to provide them with any means of self-isolating in a situation where people had to share facilities with over 100 others and bedrooms with strangers or with family members, ensuring that no-one was safe from contracting Covid-19. The Skellig Star was eventually closed in September, but only after the residents had spoken out in the media, organized protests outside the centre, and eventually, in late July, gone on hunger strike. There were subsequent and continuing Covid-19 outbreaks in many Direct Provision centers. The inevitability of outbreaks in Direct Provision and the steps necessary to ensure this didn’t happen were highlighted by MASI along with other activists in March, but the Government and the Department of Justice did nothing. The prison-like institutional conditions of Direct Provision aligned with the exploitative working conditions that many people with precarious residency status have to contend with, manifested in large outbreaks in meat processing plants and large agricultural farms that employ many people who are in Direct Provision – outbreaks that were in turn linked with clusters in Direct Provision centers.

While the response of government and big business to the pandemic has exacerbated the marginalization of people seeking asylum and highlighted the machinery of the racialized and class apartheid regime of the border, the resistance in Ireland against this machinery by people seeking asylum and their supporters has been inspiring. At the same time, the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in Ireland has been of huge importance to what feels like the building of a truly mass movement to end Direct Provision in Ireland and a real resistance to the violence of the EU migration management machine as it operates in the Republic and support for MASI in particular has increased hugely in recent months. It is important to highlight the resistance of those in the system and the human complexity and specificity of every person. As Behrouz Boochani puts it, author of No Friend But The Mountains and survivor of persecution at the hands of the Iranian government and then the Australian asylum detention complex:

[…] unfortunately, the Western gaze sees all the people as the same. But we are different kinds of people here; in fact, sometimes many of the people on Manus Island amaze me. I wonder how it’s possible that people are able to be so strong like this. Sometimes I feel powerful when I see many strong men around me, when I see them living life, when I see them resisting, when they endure this system…4

Nothing I have seen in visual representation has captured the nature of Direct Provision, the truth of the description open prison, the continuity of the system of Direct Provision within the state’s history of incarceration and institutionalization of targeted populations, as effectively or directly as Asylum Archive. As many critics and commentators have noted, the absence of any human figures in Asylum Archive’s photographic account of the Direct Provision and Dispersal system refuses what Charlotte McIvor describes as “the demand for the bureaucratic performance of refugeeness” that extends from the legal labyrinth of the application process to NGO advocacy strategies and artistic practice and representation.5 Nedeljković’s refusal to use individual asylum seekers’ images or narratives in Asylum Archive is informed by his critique of the conversion of human beings into good stories for circulation by NGOs, by the media, and indeed within creative arts practice, and is an implicit and sometimes explicit rejection of the tokenistic use that is sometimes made of asylum seekers within the advocacy sector. Instead, as scholars McIvor and Ronit Lentin point out, Asylum Archive redirects our gaze to the architecture of systematic racialized segregration, dereliction and deportability called Direct Provision. The development of a radically critical politics of representation, of the aesthetic, and of narrative (the good story) is central to Nedeljković’s project and to the political and representational work that Asylum Archive does.

The centrality of the good story to the legal process of seeking asylum and to advocacy strategies makes the politics of narrative and representation particularly fraught. In what is now called the International Protection Process, pressure is relentlessly applied to the applicant’s story, to how well this story conforms to the story that is required in order to qualify the applicant as worthy of protection. The focus of the legal process is on the applicant’s credibility and the plausibility of their story. When the Single Application Procedure – explained and critiqued by lawyer Wendy Lyon, an expert in migration and asylum law, and MASI co-founder Lucky Khambule in their audio interviews in Asylum Archive6 – was initially rolled out in January 2017 as part of the implementation of the 2015 International Protection Act, people who were already in the system were required to complete a form called IPO2. People were led to believe that this new 62-page application form had to be returned within 20 days, leading to mass and despairing panic in Direct Provision centers across the country. Terrified of being deemed non-compliant, people returned forms for themselves and their children without having had any legal advice or having been able to access their previous application to make sure the two forms were consistent. Any discrepancies or inconsistencies between the old and new applications, no matter how small or seemingly inconsequential, could be grounds for refusal of protection. The obsession with consistency and plausibility arises from the requirements of a deeply racist system whose key priority is to refuse as many people as possible, whether at the border or within the legal labyrinth of the “protection” process. Thus, the system is not designed to assist those seeking protection as much as possible, but to catch out as many people as possible.7 Part of the hostility that is written in to the asylum system is its radically uncertain temporality. The person at the centre of the process has no timetable for when the interview will happen or when a decision will be made on her case. This corrosive, pervasive uncertainty can accrue even to what might be seen as positive developments. For instance, in 2015 the Department of Justice started to give large numbers of people their papers just before and in the aftermath of the publication of the McMahon Report. They did this not through any clearly announced amnesty but by deploying a knife-edge arbitrariness that keeps people in a space of paralysis between hope and fear, not knowing whether they would get residency, hopeful that they would, terrified that they might not. Arbitrariness is not an accidental by-product of systemic incompetence but a crucial mechanisms of control at the core of the asylum and deportation regime. It orchestrates that suspended space that people describe as a kind of living death.

At the center of these varied but interrelated forms of representation is the issue of trauma – the articulation of trauma and the adoption of trauma as a measure of credibility. Scholars Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman have argued that trauma has become a form of governmentality within the asylum and deportation machine. As the testimony of asylum seekers themselves is given less and less juridical weight, and as the physical marks of suffering become less evident whether through new techniques of torture or through the passage of time in asylum limbo, trauma assumes a new importance. If there are no marks on the body to provide enfleshed testimony, then the marks on the psyche will have to be attested to for the protection applicant’s story to reach the threshold of credibility.8 Even while the words of people seeking asylum are automatically held under suspicion, they are still obliged to articulate their trauma at length in their application for protection and again, with no inconsistencies, in interview. For some people, it is impossible to articulate what they have been through because remembering and reliving are simply beyond the limits of what can be borne.

It is a simplified, media-trained version of this trauma that the good story demands. The good story is one that elicits the sympathy and pity of the onlooker. Asylum Archive’s refusal to platform individual stories or use individual asylum seekers’ images is a refusal of the neo-colonial dynamics that inform such asymmetrical relations between the person seeking asylum as passive object of charity and the person afforded the position and agency to help or “rescue” the subject of their charitable acts. Nedeljković has spoken about people seeking asylum becoming mascots of sorts for various organizations and groups, telling their story and recounting their experiences over and over in media features or having their image used to represent the authentic connections of NGOs and others to the communities they are supposed to represent and advocate for, and of his determination not to repeat this appropriation of image and story in compiling Asylum Archive. In a recent interview, Nedeljković articulates his choice of form and method in terms of the danger that telling one’s story can pose to the teller:

When you’re an asylum seeker, one day you can wake up and say oh it’s a good day, the sun is shining in fucking Ballyhaunis so I’m going to tell the truth. Next day you think, what did I say, this is going to jeopardise my case. But once it’s out there in the media it just gets reproduced again and again and your narrative, your picture is out there and there’s nothing you can do. So I wanted to do something different.

In addition to the fear of this public exposure as a life-threatening replication beyond your control, Nedeljković notes that the use of such intimate details of a person’s life or death may ultimately make little real difference:

[…] the thing about portraying humans in these situations is—you know that picture of Alan Kurdi who was killed—it lasted in the brains of Europeans or western Europeans for a couple of weeks you know, but like how many Alan Kurdis have died since Alan Kurdi? And there’s no mention of them. To have a picture there didn’t serve a purpose. So I just thought that showing the traces, or the ghosts or the remnants of people, something left after they’d been deported for example, or transferred, would tell a better story of the positionality of being an asylum seeker in Ireland.9

Asylum Archive is a historical record of the present and near past of Direct Provision and the deportation machine, and it is also specifically an artistic project. Recent years have seen the proliferation of socially engaged arts practice, political art, and art activism. Asylum Archive can be situated within this “educational turn” and a concomitant emphasis on the political and social role of arts practice. Panos Kompatsiaris summarizes this turn:

Discussions, symposia, talks, extensive publications, and educational programs have become in the past decade the ‘main event’ in exhibition practice (O’Neill & Wilson, 2010, p.12). The recent leaning toward exhibiting works of art with a documentary, journalistic, or archival nature (Cramerotti, 2009) signifies such an endeavour to generate discursive meanings that expand into social reality.10

Nedeljković’s description of the different “iterations” of Asylum Archive demonstrates its situation within this development in contemporary visual arts discourse:

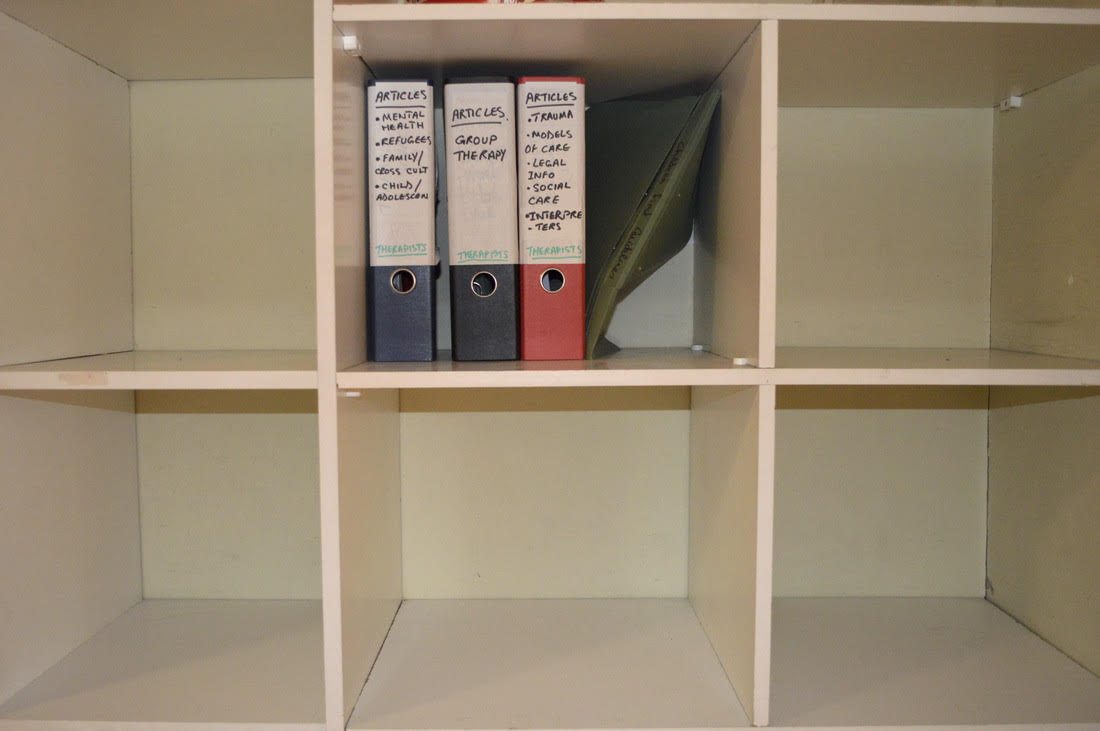

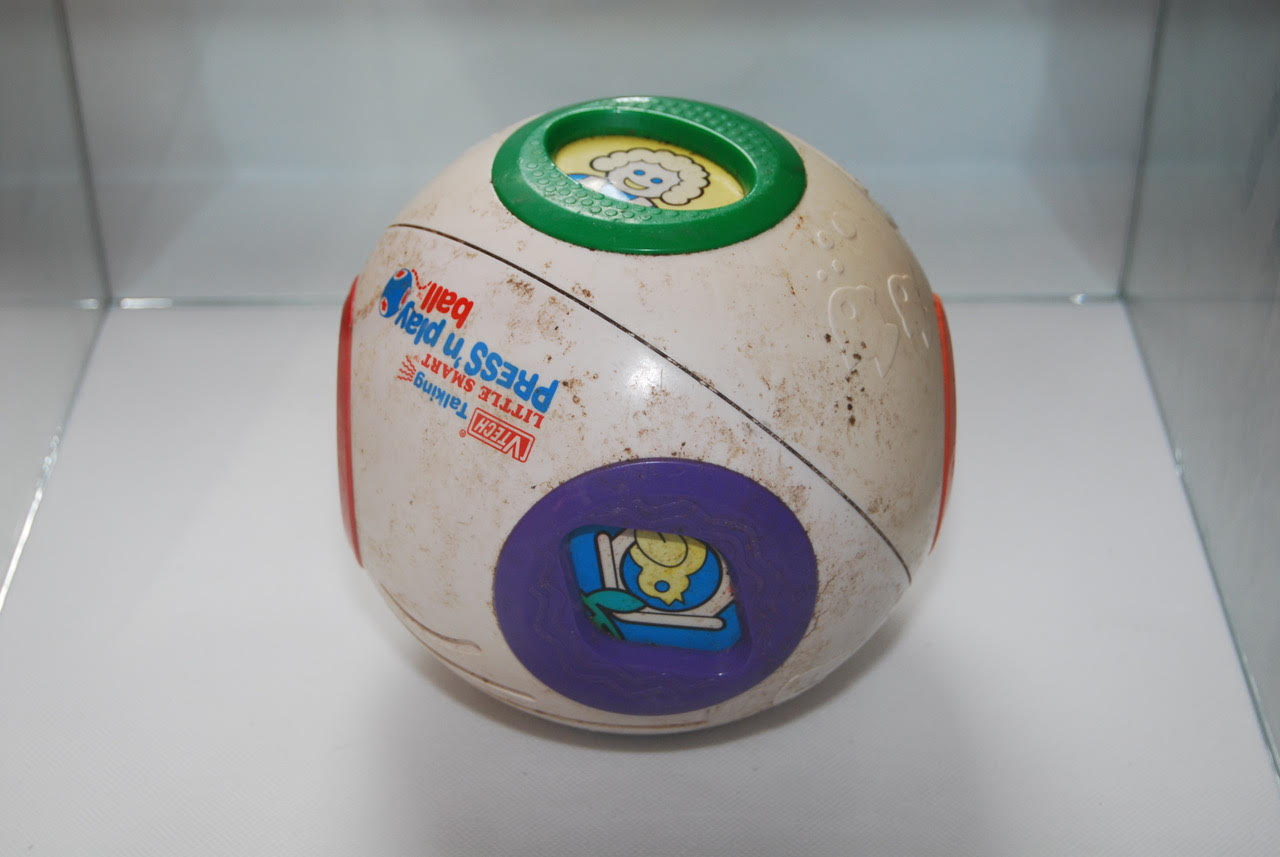

In each reiteration, Asylum Archive takes on a slightly different quality. In the exhibition at Galway, photographs could appear alongside videos and found objects. In addition, the gallery hosted a discussion panel. The same happened at the NCAD [National College of Art and Design] Gallery and in both instances, the white cube emphasised the archive’s artistic qualities. By contrast, my account in TransActions emphasises the project’s resistant qualities, arguing that asylum seekers resist the DP centres, which have been designed as sites of detention and exclusion, by reclaiming them as sites of collectivity and solidarity. Similarly, Asylum Archive resists the artistic convention of ‘humanising’ asylum seekers through storytelling by refusing to include any humans at all in the images. Lastly, the Border Criminologies version includes by far the most images, almost as if the art has to become evidence in a legal context. Taken together, these reiterations of Asylum Archive document, analyse and theorise experiences of power, authority, detention and supervision. Asylum Archive serves as a repository of asylum experiences and artefacts and it has an essential visual and educational perspective, accessible through its online presence to any future researchers.11

However, Nedeljković’s analysis of the relation between visual arts discourse, political effect, and lived realities has been implicitly and explicitly critical of the way in which asylum seekers have been represented in contemporary art practice. Migration has been a dominant theme in art works and curatorial and exhibition practices in recent years in Europe, and it has been a major lever for asserting a directly political role for contemporary art. Kompatsiaras takes the 2002 Documenta 11 event as a watershed in terms of the imagining of art practice and the large-scale art event as a space of potential radical, political, and emancipatory practice. Vast in scale and ambition, recent and controversial landmark events such as the 2012 edition of Manifesta and in 2017 both Documenta 14 and the Venice Biennale have been animated by this ambition. Whether the ambitions of such events are realizable or even appropriate in the contemporary context of the horrors being perpetrated on the EU borders and detention camps against people seeking asylum is a serious question. Refugee tents made of marble overlooking the Acropolis, vast obelisks dedicated to refugees and migrants and valued at half a million euro by the artist, art-films using documentary techniques that manipulate people at their most vulnerable–it is appropriate to question the emancipatory effect of such works.12 There is a fundamental conflict between the artist’s aesthetic and conceptual ambition in contemporary visual arts practice and the grim reality of the tens of thousands of people murdered by EU “migration management” policy and the many tens of thousands and more locked up in detention and coping with multiple forms of dereliction across this continent as well as in Turkey and North Africa at the behest of the EU.

The first time I encountered Asylum Archive and Vukašin himself was at an academic symposium in June 2013. Vukašin was presenting on a panel on “Migration, Displacement, and Creative Practice” as part of a “Digital Humanities Exploratorium” investigating “Pathways to Interdisciplinarity, Creative Praxis, and Digital Humanities Research.” I was the panel chair. The symposium was described in the kind of language familiar to anyone acquainted with the neoliberal university and its favored registers, where all endeavors must be articulated so as to maximize their use-value for funded projects, institutional outputs, and applications for promotion. However, whatever my scepticism now about the purpose and ultimate beneficiaries of such symposia, my encounter with Asylum Archive and with Vukašin was without a doubt transformative for my felt understanding of what Direct Provision and the deportation regime really means for the people subject to the machinery of “protection.” It brought home to me the absolute culpability of the Irish state and myself as privileged white settled citizen-subject of that state in this regime of slow death.

I am an academic by profession, but over the last number of years I have been increasingly absorbed not so much in the academic analysis of “migration management” or in elaborating theoretical frameworks for unpacking the asylum and deportation regime, but in making some kind of contribution to the asylum-seeker-led movement to dismantle these oppressive, death-defined systems. Asylum Archive and Vukašin have been key to this process over these years. The expansion of Asylum Archive to include the witness and analysis of radical organizers and movement leaders such as Joe Moore of ADI (Anti-Deportation Ireland) and Lucky Khambule of MASI is a testament to the interconnectedness between Asylum Archive and the vital organizing work that such radical grassroots groups do and have done. As Lucky Khambule would say, we are all singing with one voice.

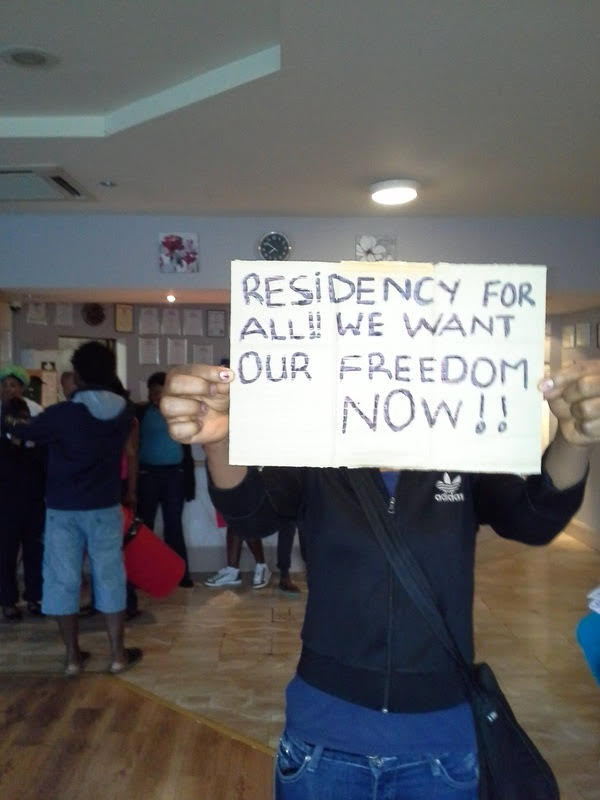

Though Asylum Archive has had many exhibitions over the last few years, I recall in particular an exhibition in Unit 4 in Basic Space, during Refugee Week 2018. I sat on a chair beside the projector and watched the slides shuffle past, the grim catalogue of contemporary institutional abuse and human rubbishing. Vukašin pointed out the slide of an old hostel in Salthill in Galway, Southern Hills, as myself and my partner Sarah had been with him when he photographed it in 2016. A Google search has told me that the building sold in 2017 for 581,000 euro. It is listed as formerly a guesthouse and restaurant; no mention, of course, of its former use as a Direct Provision hostel. There is something jarring and relentless in the sound of the slides clacking through on the old projector and while the slide show continues I listen to the recording of Lucky talking about the 2014 resident protests in Kinsale Road Accommodation Centre and other centers and the coming together of MASI. The significance and legacy of the 2014 protests is hard to overstate. People penned up in annihilating situations of enforced dependency and isolation, living in fear that any infraction of any rule imposed by management, no matter how petty and infantilizing, could result in being transferred or deported, overcame their fear, confronted power, and forced the majority population to see and hear them. In the recording, Lucky describes the KRAC lockout and the DP protests, and just how significant an achievement these were. He talks about the working group and the attempts to stifle resistance. He recalls how MASI came into being. He signposts the obstacles and hostilities that a truly independent asylum-seeker led movement came up against from various vested interests. There is another asylum archive underlying Lucky’s account that should also be documented in time.

The 2014 Direct Provision protests and the protests against the working group are recorded in the “Contribute” section of Asylum Archive, which includes photographs sent in from protestors in the Montague Hotel in Portlaoise and Lisseywollen in Athlone (included in the subsection “Resistance”) and a further subsection on “KRAC Asylum Today,” with photos from the strike and from the protest (along with ARN – the Anti-Racism Network Ireland – and ADI) outside the final Working Group meeting in the Department of Justice in 2015. I recall Vukašin taking part in another conference in UCD [University College Dublin] in 2014, just a month or two before the DP protests, where he spoke about Direct Provision as a site of resistance as well as “incarceration, social exclusion or extreme poverty.”13 The centers also, as Nedeljković has since written, “constitute oppositional formations of collectivity and resistance against State policy in which different nationalities and ethnic groups exist and persist despite the very conditions of confinement created by the state.”14 The understanding of DP centers as sites of resistance as well as abjection resonates with Imogen Tyler’s analysis of the 2008 naked protests by immigrant mothers in Yarl’s Wood, a women’s detention and removal centre in England. Against the framework of “bare life” elaborated by Giorgio Agamben in his biopolitical theory of homo sacer and the figure of the refugee (a framework that is significant for Asylum Archive), Tyler asserts that “the refugee” is not a passive, abject figure without agency, though this representation of the refugee “predominates within legal, charitable and academic discourses” and especially within the advocacy sector where there “are enormous pressures …to produce testimonial accounts which will ‘shock’ the system into policy change.”15 This underlines the tensions that can exist between autonomous grassroots movements and funded advocacy organizations. The power of people in the asylum system themselves taking action and speaking on their own behalf, independent and unmediated, challenges and undermines the stereotype of the “protection applicant” as the passive figure of charity who must be spoken for and on whose behalf the experts intervene. Asylum Archive forces us to see and confront these contradictions and tensions. In this way, Vukašin’s work has built a politically effective archive in the present and for the future of the routinized “soft” torture of people seeking asylum in the state’s contemporary camps, while also demonstrating that the refusal of complicity in ethical, political or aesthetic terms is an ongoing project that must be continually renewed.

This essay is a revised version of an essay originally published in Vukašin Nedeljković, Asylum Archive (Dublin: Create/The Arts Council of Ireland, 2018).

For more information: http://www.asylumarchive.com

***

Anne Mulhall

Lecturer in the School of English, Drama & Film at University College Dublin and co-director of the UCD Centre for Gender, Feminisms & Sexualities.

Vukašin Nedeljković

Visual artist and activist based in Ireland. He initiated the multidisciplinary platform, Asylum Archive as an online resource, critically foregrounding accounts of exile, displacement, trauma and memory, complemented by the recent parallel platform of resistance. Fortress Europe https://www.fortresseu.com/

1 Arundhati Roy, ‘The Pandemic is a Portal’, The Financial Times, 3 April 2020 https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca

2 Patrick Kingsley and Karam Shoumali, ‘Taking Hard Line, Greece Turns Back Migrants by Abandoning Them at Sea’, The New York Times (14 August 2020) https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/14/world/europe/greece-migrants-abandoning-sea.html

3 Traveller refers to communities that share culture and traditions predominantly marked by a nomadic way of life. In Ireland, the Traveller community has suffered a long history of multiple and intersectional discrimination including poverty, unemployment, lack of educational opportunity, decreased life expectancy, cultural bias, and social stereotyping. Although they predate the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922, from that point on the Magdalene Laundries were institutions of incarceration as well as for-profit enterprises run by Catholic religious orders. The women and girls confined in these institutions included “those who were perceived to be ‘promiscuous’, unmarried mothers, the daughters of unmarried mothers, those who were considered a burden on their families or the State, those who had been sexually abused, or had grown up in the care of the Church and State.” See Justice For Magdalenes Research web page for further information. http://jfmresearch.com/home/preserving-magdalene-history/about-the-magdalene-laundries/ [Accessed October 2020]

4 Behrouz Boochani and Omid Tofighian, ‘Manus Prison Theory: Borders, incarceration and collective agency’, Griffith Review 65 (August 2019)https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/manus-prison-theory/

5 Charlotte McIvor, “The Power of the Everyday: Looking Away from Bodies and Towards Ephemera” in: Vukašin Nedeljković, Asylum Archive, (Dublin: Create/The Arts Council of Ireland, 2018) p.1

6 See ‘Wendy Lyon’ and ‘Lucky Khambule’. Asylum Archive http://www.asylumarchive.com/audio.html

7 There are so many examples of this it is difficult to choose just one, but this example may serve as part-illustration. There are ongoing issues with translation and interpreters in the application process; the standard of interpreter available to people during their crucial interviews has been heavily and consistently criticized and there is no doubt that below standard translators lead to people being refused protection. Instead of working to improve this, however, the IPO instead introduced a new system of language analysis testing in 2016 that “involves the examination of an individual’s speech in order to assess…whether the individual could be placed in the geographical area of speech community from which they claim to come. Where the language analysis report indicates that the applicant is not from the geographical area or speech community to which they claim to belong, this becomes a credibility issue for exploration at substantive interview.” Summary Report of Key Developments in 2016 (Dublin: Office of the Refugee Applications Commissioner, 20016), p.8.

8 See Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman, The Empire of Trauma: An Inquiry into the Condition of Victimhood (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2009), pp.250-274.

9 ‘Tenancy: Asylum Archive – a conversation between Vukašin Nedeljković and Lily Ní Dhomhnaill, MAP Project (June 2020) https://mapmagazine.co.uk/tenancy-asylum-archive

10 Panos Kompatsiaris, “Curating Resistances: Ambivalences and Potentials of Contemporary Art Biennials.” Communication, Culture & Critique 7 (2014): 79.

11 Vukašin Nedeljković, “Reiterating Asylum Archive: documenting direct provision in Ireland.” Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance. 23:2 (2018): 290-292.

12 Rebecca Belmore, Biinjiya’iing Onji (2017); Olu Oguibe, Obelisk (2017); Artur Żmijewski, Glimpse (2017).

13 Vukašin Nedeljković, “Direct Provision Centres as Manifestations of Resistance.” TransActions: dialogues in trans-disciplinary practice 1 (2015). http://issue1.transactionspublication.com/2015/06/09/direct-provision-centers-as-manifestations-of-resistance/

14 Vukašin Nedeljković, “Asylum Archive: An Archive of Asylum and Direct Provision in Ireland.” Border Criminologies 4 May 2016. https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2016/05/asylum-archive

15 Imogen Tyler, Revolting Subjects: Social Abjection and Resistance in Neoliberal Britain (London and New York: Zed Books, 2013), p.114.