Ulysses and the Complex Dimensions of What is Hidden and What is Shown

Angela Mascelani

He said he asked himself: Where does this earth come from? Where is it? And where is it going? Was it created, generated or born? He said that he liked to ask questions, that it was that kind of question that he asked … He said he had no teacher … and that the answers are there; that each one needs to be attuned to the answers. He insisted that when someone photographs, they copy. And everything stays the same … He was silent for a brief moment and then said the clay was alive …

His monologue was so strong that the works seemed to move, touched by the wind of his words.

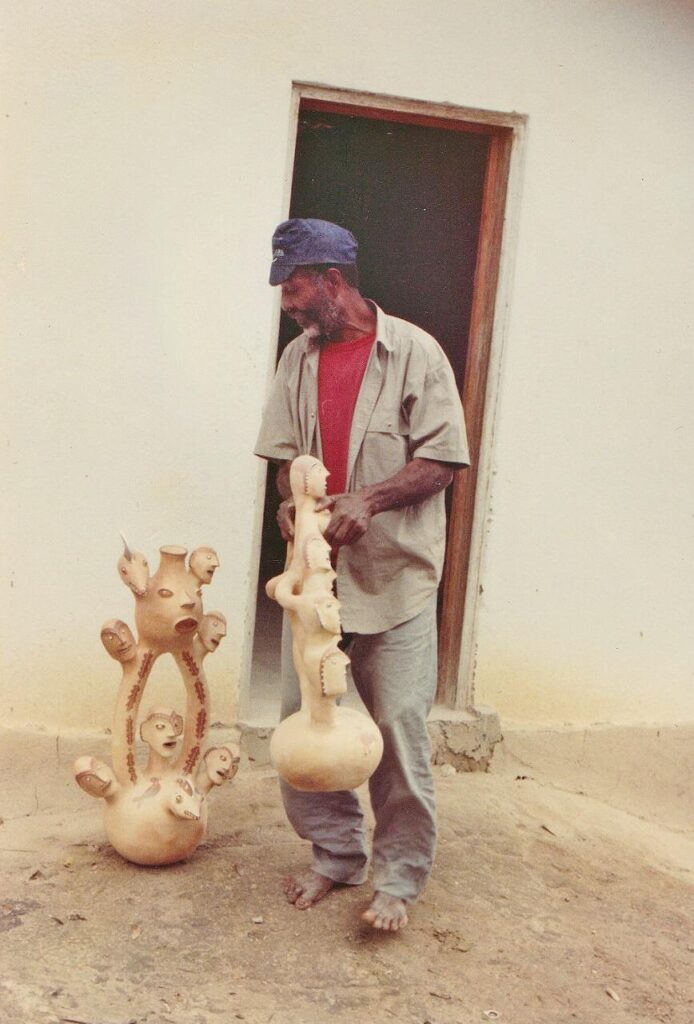

I’m Ulysses! I talk to the sun, to nature, to oxygen. My pieces don’t mix. They are my stuff, I don’t copy, I invent. They go away with whoever buys them, but I go with them. They talk to me. I speak to them wherever they are. I have vision. So I have value. Everything I do comes out of nature, out of my head, out of my invention.

Ulisses Pereira Chaves was born in 1929, in Córrego Santo Antônio, near Caraí, in the Jequitinhonha Valley, Minas Gerais, where he also died in 2007. Raised amidst pottery makers, he continued the family tradition, establishing himself as a formidable presence and standing out as a “popular artist” in a region where the production of utilitarian and figurative ceramics is mainly the work of women.

Historically determined and a sociocultural and territorial fact, the notion of “Brazilian popular art” refers to a total phenomenon that is at same time social, economic, cultural, and aesthetic, including the narratives, works, authors, and discussions organized around it.1 It does not designate an artistic style, a technique or even a single type of object. On the contrary, it circumscribes a field of production that establishes connections with different artistic languages, in which creativity and individual authorship occupy a central place. The notion is linked, almost always in a visceral way, to the vast and democratic field of handicrafts, since it is often from there that those individuals who stand out with a particular work come from. The designation of something as “popular art” is related less to a rigid discussion about its boundaries than of what may or may not be considered as art. In this sense, it constitutes a territory that questions the hierarchy between art forms and allows us to see the transit – almost always ambiguous, and at times confusing or conflicting – of artisanal productions that are considered peripheral, towards the established system of visual arts.

The term “popular art” is very broad. In this essay it refers to the three-dimensional production of modeling in ceramics and sculptures in wood, iron, and fabric, made by artists from so-called popular classes. According to its contemporary use, popular art refers to non-hegemonic forms of artistic making from the poorest and peripheral regions of the country, and to works created outside of any schooling or constituted art systems. In this sense, even considering that the qualitative use of the term “popular” implies other problems that cannot be ignored, or remain hidden, such as the blurring of gender specificities, African, indigenous or territorial matrices, etc., or seeming to dialogue with dichotomous perspectives, naming this production as such in the Brazilian context is understood as a strategy. One that aims at making society see that outside so-called “cultured” contexts, in invisible and silenced areas, amongst the self-taught or those who have learned through family tradition, there is an aesthetic production that can and should be understood as art that, in most cases, is not.

Although the poetics and expressive force present in popular creative productions are recognized in some contexts, and is plain for all to see as it occurs in all regions and with regularity, its invisibility in the artistic field is noteworthy. The works in general are understood as handicrafts aimed at commercialization and circulate timidly in professional art circles. Because they are not part of a structured circuit, the recognition of authors / artists is precarious, meaning they are continually referred to as recent “discoveries”, no matter how much time they dedicate themselves to their work. An additional issue that exacerbates this is that this art is not part of school education, and is absent from books and anthologies of Brazilian art, with rare exceptions, such as, for example, Mestre Vitalino.

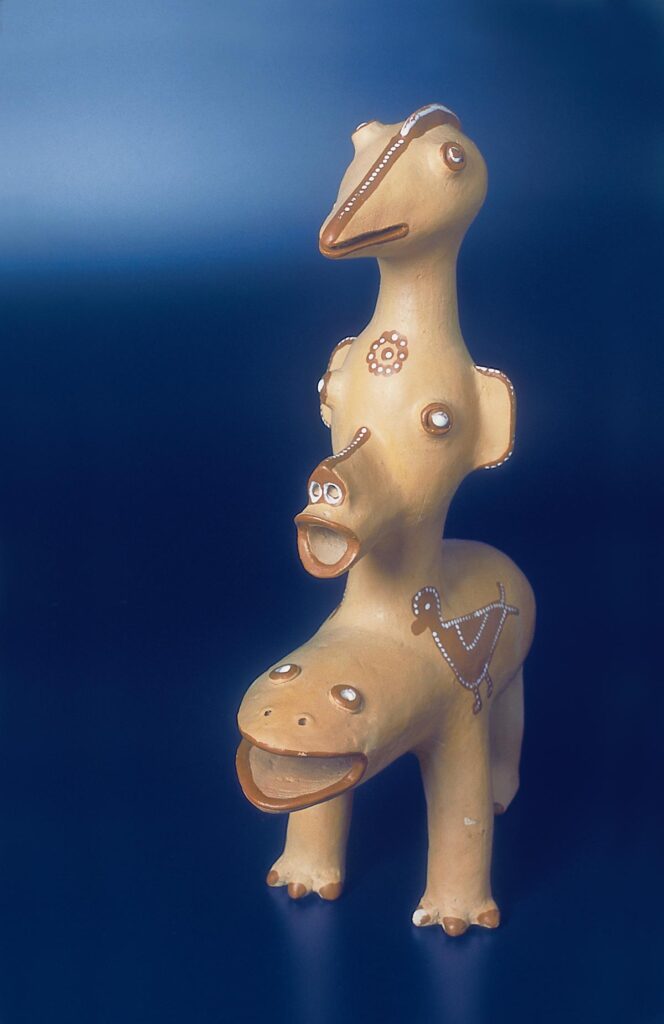

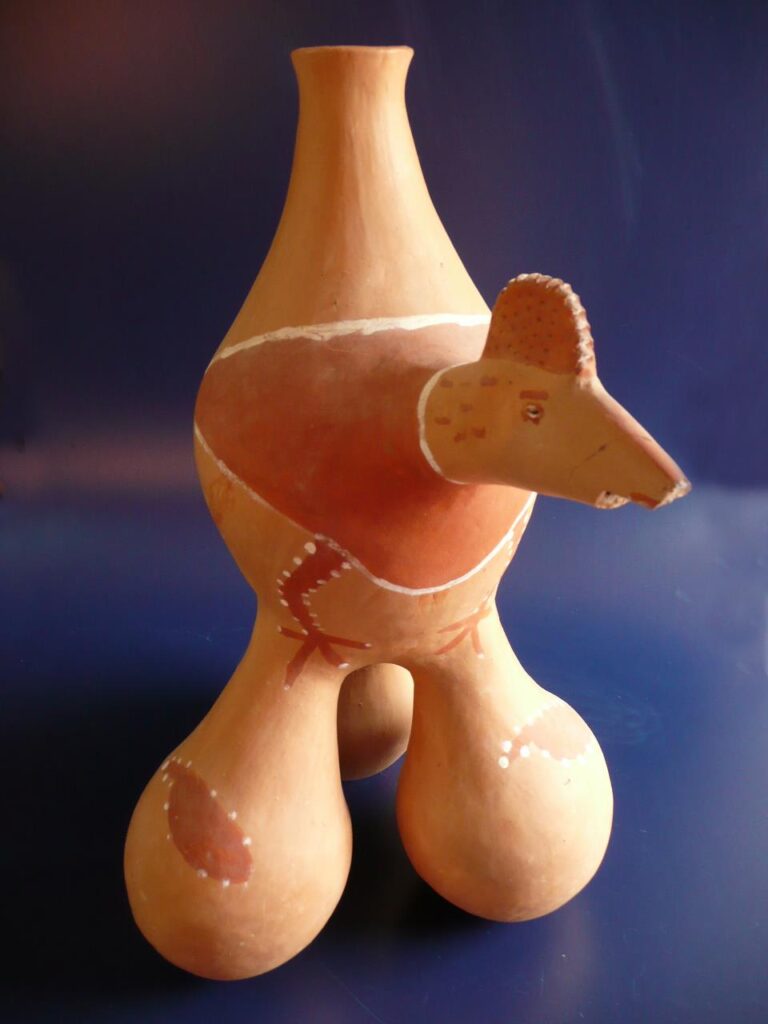

The Face of an Animal, The Body of a Person: The Opposite also Exists

In the early pieces by Ulisses Pereira Chaves, we can recognize the prevalence of domestic animals, such as chickens, or other animals from the surroundings of the house, such as lizards and, also, moringas [traditional ceramic jars to store water]. Over the years, his creation evolved, taking on leaner forms and formally more elaborate ones. He created moringas-birds with ample curves; other pieces with tiny feet and heads; or human figures with elongated necks, establishing new meanings for this traditional form. He invented a kind of reptile, with thick, structural legs. He put a horse’s head on a man’s body, evoking the image of the minotaur. He invented totem sculptures, with generous shapes, in which multiple heads intertwine, in a kind of repetitive continuum; their bodies adherent, their heads, seething.

Photo: Lucas Van de Beuque, Collection Museu do Pontal.

Most of his compositions reveal invented beings that do not exist in reality and speak of the presence of the supernatural in his life.

Everything I do comes out of nature, out of my head, out of my invention. The pieces are matter that answer me. (…)

A practice that made anthropologist Lélia Frota question: “Is this expressionist, surrealist, or [deriving from] another experience, one that coexists with the supernatural with the greatest naturalness, considering it more true than the facts perceived by all of us in our day-to-day lives?”2

It was in a conversation with Frota that Ulysses declared that it is the invisible elements that determine the unique characteristic of each work because they are “in permanent mutation”.3 Although the artist had some recognition during his lifetime, his works were not monetarily valued, a reality common to all those working in this area. Even with some renown, because in the early 1990s the uniqueness of his talent was already well known, he never entered the elitist world of Brazilian visual arts, with its Eurocentric paradigms, verticalisms, and the firm refusal of other narrative possibilities. Ulysses’ recognition was largely restricted to the specialized field of those interested in Brazilian popular art, collectors, and scholars above all.

Precisely because this type of production is from an impoverished region of the Jequitinhonha Valley, historically associated with the refuge and resistance of black populations and quilombas [Brazilian hinterland settlements founded by people of African origin many of whom were escaped slaves], in a hierarchically less central context, the aesthetic dimension of what is done there is not always recognized as a personal creation, whose authors have unique identities. Production, as a whole, and despite its particularities, is seen as handicrafts, and pejorative interpretations associated with repetition, copying, and merchandise, are latent. The label of handicraft is not specific to this region, but refers to the creative production of the least economically privileged in Brazil. This kind of “historical erasure” of the intellectual and artistic production of the popular strata has contributed to reinforcing prejudices, creating exclusions, and market categories for those who might be seen or considered as an artist, in addition to widening social and economic distances, reproducing perverse hierarchies.

Despite all this fog, Ulysses, and his impactful creations, prevent us from being indifferent. We need to listen to him! With him, we are called to look again, see anew, walk along the paths of uncertainty, and to deeply rethink what exists beyond contradictions.

When Fragments are Unity

The first image that strikes you, arriving at Ulysses’ home, is the wooden fence that surrounds the property, marking the entrance to where he lives.4 At the top of each post, there is a spiked head, a half of a broken face, or piece of a broken limb, “popped” during the firing of the pottery. Together they make up quite a dramatic, indeed bleak, scenario. Whether it’s the broken bodies, or the evocation of lack, something is no longer whole. Or, perhaps, they conjure ideas of ruin and deterioration.

But it is not only that. They also seem to bring shards back to nature, in a process where nothing is leftover. In a new context it is as if the broken works received some type of restoration.

Georg Simmel says that:

[…] the ruins of a building mean that other forces and other forms – those of nature – have developed and replaced what in the work of art had been destroyed and disappeared and that a new totality, a particular unity born from the rest of art still lives in [the ruins] and [it is] this part of nature that lives in them now.5

By displaying the pieces in a new configuration, Ulysses recreates a new totality, underlining the completeness of his creation, regardless of whether something was broken or not. There, his works take on new meanings, remain active. Living matter, whose amalgam is determined not only by the action of fire, but also by its cosmic nature.

Surrounding the house with fragments reinforces and makes explicit the links between artist, work, and natural environment. It suggests, as Simmel says about ruins, that: “a human work is perceived almost as a product of nature. The same forces that shape the mountain’s contours – climate conditions, erosion, landslides, the action of plants – reveal their effective presence, ([weathering Ulisses’] great walls)”.6

Ruins have the ability to expose and integrate opposing and conflicting forces. Amidst ruins, one thinks of rises and falls, the old and the new, the past and the future and, above all, the human incapacity to prevent the advance of time. Yet in their positioning by Ulysses those pieces of pottery do not allow for any kind of nostalgia. They lead us to think that modeling an object, establishing a discourse, and inventing new destinations for loss and error are part of the “same” process. Something that reinforces the artist’s vision of the world revealing the connections that act upon and drive him. Somehow, for Ulysses everything is creation. Nothing is leftover.

The reallocation of what cannot be sold, because it has broken, also calls attention to the concrete work of ceramics, to the fragility of baked clay, exposing the process with its contingencies, errors, and failures. It reveals what almost always remains hidden in the making of ceramic work itself – risk and the lack of control – symbolically reinforcing what is present in Ulysses’ words, yet, not everyone who visits him seems to understand.

I cannot know whether or not people like my pieces. No one can answer for someone else. Each person has a meaning and chooses the meaning and neither I nor anyone else can know the meaning that people give to the pieces. (Ulisses, 2005).

Ethnography of an Encounter

The first time I visited Ulysses at his home was in 1995.7 His fame as an eccentric and difficult person had exceeded him. He received me in a friendly, albeit tense way. He showed me the workshop where he molded the clay. Then, a small room where he stored the finished pieces, which he did not allow me to see freely, keeping the door just a little ajar. Without me asking him anything, he said that nothing was for sale there. He told me that everything was commissioned and that I couldn’t have any piece.

I watched for a while. Trying to see what was possible, without demanding anything more from him, feeling his rhythm. His pieces feature smooth, baked, and sleek clay, no rough textures. The surfaces retain the color of the earth and are painted with natural pigment inks. The forms, both original and elegant, are disturbing.

Then we went to the living room, a simple and rustic home, well ventilated and pleasant. We talked. Or rather, I was silent and he did the talking, in a continuous flow, mending one subject in the other. One moment he was exalted, the next withdrawn, silent. His wife Maria José came and went. She watched him and me and said nothing. We listened to our breaths. Outside, the sun was very hot.

Through the window, I saw that some people – his children, and sister Ana (whom I later came to know) – were close by. No one entered the room.

I told my wife that you were coming. I saw you coming here tonight, in my dream.

Just as Ulysses has a capacity to anticipate what will be experienced, a power to know things before they come to reality, he also understands his works as autonomous elements, although inseparable from himself. Creator and creature with their own identities, but, paradoxically, both, one, viscerally connected to the earth.

Material here is clay. If you take one, I’ll talk to my piece wherever it is. Each piece answers me. If you ask, it says nothing. If you ask, it is silent. My pieces speak to me.

When I asked if I could photograph him, he refused, only allowing me to photograph the works.

I don’t want my picture, my strength [as if] stuck on film, in an interview. I don’t allow photography here. If you want to photograph, show the project. I teach. I don’t teach for free.

I ask if I can pay to take the photos. He says no. And I realize right away that this is not the issue.

I talk to the sun, I don’t copy anyone. I’m not like the others who don’t know what the pieces say.

He brings a flyer-poster as an example of what he doesn’t like. In it his pieces appear alongside photos of the town of Caraí, the church, and the market.

Why did they put the church and the market? Where is this? Here? No, not here. Here is not there. I am here, in my house.

Ulysses shows his surroundings. The house is positioned on the highest ground of the property and he opens out his arms and makes me look around, as if visitors also need to notice the obvious. Here, it is not there.

Back to the text of the poster, where his importance as an artist is recognized and the city of Caraí and its landmarks are used as a reference for his location. The text also qualifies him as a ceramist from the Jequitinhonha Valley. But that doesn’t seem to appease his dissatisfaction. He leaves and comes back with another big poster, from an exhibition, where his work stands out, covered by his name, in bold letters.

There, there. I’m not there! In my house I’m the boss. Nobody takes pictures here if I don’t want them to. And people come here to photograph and put my name on paper.

I don’t reply, but he seems to have a lot to say on the subject, as if he were waiting for that moment, accumulating answers / outbursts to questions that afflict him. Perhaps that is why he speaks non-stop, as if the words were being unstuck out of from a choking throat. His speech is quick, uninterrupted, without punctuations indicating a change from one subject to another, making it impossible to follow and understand in detail the development of the stories he was narrating or even follow exactly what he was saying. Its pace was dizzying.

However, the meaning of his speech is not lost. It is evident that his indignation is related in some way with what he sees and no one else seems to see, from what he hides from the other’s gaze, all the while seeming obvious to him, and to what he sees as disrespect for his thinking and principles.

Having his work printed on paper, even in praise, violates his choices. For his creation is not an object for the other or the market. Even though the artist lives off his production. However, between him and his work there is an intimate connection. This encourages him to seek a concrete relationship, eye to eye, with those who acquire his pieces. For Ulysses, nothing is dissociated. This makes him the kind of artist for whom his home and what happens in its surroundings – relationships, people, space – makes up a kind of “micro-climate”. His environment is his way of existing and relating to the world.

In another visit, made in 2005 (this time with Lucas and Moana Van de Beuque), Ulysses says that each person has his own gift for making art. And that the people who look for him “want this, want that, want to be the artist’s own teacher! Because my pieces are an image of what I do, not an image of something. [They are] image and likeness of what I am ”. With this speech, already in the first few minutes of contact, the artist goes straight to the point – his creation is, in itself, origin and end: his own expanded body. The very image and likeness of who he is.

Throughout his life, everything appeared as integrated. Modeling in clay is equivalent to plowing the land, planting and harvesting food, cleaning a river spring; encountering clay, “lifting the body” of a piece, as is the expression commonly said by potters in his region. And, even in welcoming us as visitors, he draws us as participants into his unique reality.

Nature and the Refusal of Divisions between Beings: For Ulysses, All are One

In our first meeting, I could sense his effort to communicate something that seemed for him self-evident – that man and nature are inseparable. He spoke with a raised voice, brusque tone, and strong energy. Perhaps this effort was necessary to make it clear that the oppositional relationship between the human and the natural, between nature and culture – central tenets of modern Western viewpoints – are mistakes that have been going on for too long.

Either by creating a mythological bird or by producing his ghostly fences, with their spiked heads, Ulysses entangles us in his tormented – and in a way, lucid – mental process. His deep insight into his art speaks of the conception of life as nature. And it feeds back into the notion of nature as a ceaseless creation, in which Ulysses is a present participant, with his pieces of baked clay, in which the human unfolds into the Other – the fabulous animal.

Imaginary beings appear widely in popular sculptural production. As a lateral but consistent production, it is found in the creation of artists from different cultural regions of Brazil, such as Mestre Vitalino (Pernambuco (PE), Ciça (Juazeiro do Norte, Ceará (CE), Antônio Rodrigues (PE) and many others.

Photo Anibal Sciarreta, Collection Museu Casa do Pontal.

Among those for whom this theme is central, Manoel Galdino, from Pernambuco, the authors of masks from Cazumba, in Maranhão, and Ulisses Pereira Chaves, particularly stand out.

Photo Lucas Van de Beuque, Collection Maria Mazzillo, Acervo Museu do Pontal.

For some, the inspiration seems to come from the stories they heard about relating to some other time in the past, or from mythical narratives, with their surprising and frightening characters. This does not seem to be the case with Ulysses, who is very much connected in the present with nature and its mysteries. The form and themes emerging from his modeling of clay is perhaps best articulated by another artist from the region, Ulisses Mendes, from Itinga, noted for his work with wood. He describes one day that he went to visit Ulisses Pereira Chaves, at his home:

So I went there, it is difficult to get to his house. The greatest artists live a long way from the city. Interesting. Away from the city, in the countryside, far away. Go up a hill, down a hill. There’s the good artist. Whoever lives a lot with nature, that type of thing, gets very attached to God, they’re alone there. There he perfects his artistic side, and creates that work with sound of nature. The forest, natural sound, the work also roars. It roars, it has that sound of the woods, the mountains. If we go too far into that, you hear voices, you hear the wind talk. I’ve gone so deep into this world that you end up speaking spiritual, original, scientific, where I’ve heard the waters sing, [something] I’ve heard many times.

What is this other Ulysses talking about? He speaks of the refinement of the senses, opening up to other meanings that are silenced, expanding sensitivity and surrendering to the event. He speaks of the importance of loneliness and communion with nature, something that seems to be, for these artists, the very condition of creation. To hear the waters sing is to participate in the freshness of the waters, the momentum of the waters, it is to drink at the source of inspiration. An inspiration that is not rushed. That knows that time is necessary. Art time.

Ulisses Pereira Chaves lived all his life in this rural environment on a farm a few kilometers from the small village of Caraí. His experience is that of most rural men, those who plow land impoverished by mining ores. Someone who, along with his Afro-Brazilian ancestors, managed to resist and get by on the land, and through art, invented the non-existent. This extensive region is also shared with different indigenous populations. Currently the Maxakali people (Yãy hã mĩy) live between the valleys of the Mucuri and Jequitinhonha rivers. The Maxakali people live in four areas of Minas Gerais:8 in the villages of Água Boa, in the municipality of Santa Helena de Minas; in Pradinho and Cachoeira, in the municipality of Bertópolis; in Aldeia Verde, in the municipality of Ladainha, and in the district of Topázio, in Teófilo Otoni. Their lands constitute some of the smallest indigenous territories in the country, home to a total of about 2,500 people. The Krenak village, also located just over 200 km from Caraí, is the birthplace of the indigenous philosopher Ailton Krenak, author of Ideias para adiar o fim do mundo [Ideas to Postpone the End of the World]. In this book, and in his reflections, the author criticizes those who do not understand that the links woven between nature and humanity are fundamental to survival.

We are nature and this interdependence is vital. If we ignore this, we die. The idea of a life separate from nature can only mean the end of our experience of sharing life on earth with other beings, with the forests, with rivers, with other species, including those that we know are on the extinction list and that we treat as if it were just some inconsequential news. As if these numbers were predictable and that it is not an alert for the next guy who will be on the list: homo sapiens, ourselves.9

Perhaps this is the experience that Ulysses tries to convey to those who seek him. And in that certainty, there is nothing hidden. Everything is explicit!

The indigenous influence in the ceramic art of the Jequitinhonha Valley is the subject of the book As noivas da Seca [The Brides of Drought] by Lalada Dalglish.10 The author establishes broad connections, finding, in the crafts and art of the Valley, links with the production of indigenous peoples from other Brazilian regions and even from other countries. She points out visual connections existing between the “moringa [water jar] with four legs”, made by indigenous populations of the Central Andes and the “moringa tripod”, made in Minas Gerais in the 19th century. Similar pieces to these, found in pre-Columbian Mexico and Karajá ceramics, can be easily seen in various locations in the Jequitinhonha Valley, in sculptures with a single body (human or animal) and two or more heads (idem) found both in Caraí, made by Ulisses Pereira Chaves and family, as in Turmalina, Campo Alegre, made by Rosa Gomes da Silva and others, such as the so-called “twin” sculptures.

Photo: Lucas Van de Beuque, Collection Museu do Pontal.

Even if they existed before, with Ulysses, these images are born as if for the first time. He receives them from the winds and breezes that come from afar. And, until the end of his life, at the age of 78, he undertook to expand their meanings.

Focusing on the art and thought of Ulisses Pereira Chaves provides an interesting opportunity to think about the multiple semantic dimensions of the “hidden”. If, in a way, hiding is viscerally linked to its opposite, suggesting that there is something to be revealed, it can also indicate an absence, whether intentional or not. The hidden allows us to suppose a double movement, in which the hidden is passive (without place, ignored, unknown) or active (hiding, because it is so wished). There are still other dimensions, such as when the artist makes his work the messenger of the invisible, bearing qualities that are not shown to everyone, but only to those who seek, among whom he is included). There is also the hidden and intangible communicative links that remain between the artist and his works. Further adding to this multiplicity of meanings is the complexity of the existential and cosmic creation of life and work. As such, it also points to the “hidden” links between pre-Columbian imagery and Siamese pieces and creatures, as incorporations and resurgences of an immemorial unconscious that migrates into the hands, clay, and earth of Ulysses’ production.

The “hidden” can also be a dimension of choice, and a certain strategy, when, for example, the artist decides what should be shown and to whom; for example, keeping the door ajar, implying that there is something there that he does not want to show – or that should not be seen.

Yet the remarkable invisibility experienced by Ulisses Pereira Chaves in the context of the art world and its many conflicts, are not just about him. It refers to something bigger, more profound, infrastructural and, above all, to the prejudices that support the system of art and culture and reinforce criteria of exclusion and exclusivity – the basis of the hegemonic definitions of what art is and who can be recognized as an artist. These are just some among many issues that keep him, and other popular artists, on the sidelines. Preventing the recognition of his knowledge, devaluing the traditions to which he is linked.

Although indignant, and expressing his dissatisfaction, the artist never got tired. Speaking of invisible things, talking with the sky, with plants, with the sun and with nature, Ulysses bequeathed us, in addition to works, a holistic worldview, absolutely necessary and contemporary. A cosmological view where each part can be a whole and in which the earth of clay, becomes the whole Earth.

***

Ângela Mascelani

Anthropologist, curator and art director. She has been director and curator of the Museu Casa do Pontal in Rio de Janeiro since 2004. She holds a doctorate degrees in anthropology and a masters in visual arts both from the Universidade Federal de Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Her publications include O Mundo da Arte Popular Brasileira (Ed. Mauad, 2000); Caminhos da Arte Popular: O Vale do Jequitinhonha (MCP, 2008) and O que você vai levar – material educativo complementar ao ensino de artes plásticas populares (MCP, 2010). She has curated numerous exhibitions nationally and internationally and co-directed award winning documentaries such as focusing on art and popular culture, health and welfare for women in Brazil such as Parteiras do sertão – a magia da sobrevivência, (1993); Terra queimada de sangue (1987), Prêmio Tucano de Prata no Festival Internacional de Cinema e Vídeo do Rio de Janeiro e Artistas Cazumbas and runner-up Prêmio Pierre Verger (2020).

1 MASCELANI, Angela. O mundo da arte popular brasileira: Museu Casa do Pontal. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad. Rio de Janeiro. 2002.

2 FROTA, Lélia Coelho. Pequeno dicionário da arte do povo brasileiro – século XX. Aeroplano: Rio de Janeiro, 2005, p.406

3 Ibid.

4 MASCELANI, Angela. Caminhos da Arte Popular: o vale do Jequitinhonha: Museu Casa do Pontal. Rio de Janeiro. 2010.

5 SIMMEL, Georges. La Parure et autres essais. Trad. Et présentation de Michel Collomb, Philippe Marty y Florence Vinas. Paris. Ed. de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 1998, p.259.

6 Ibid, p.113

7 Todas as falas de Ulisses Pereira Chaves, transcritas neste artigo, foram ditas em encontros com a autora. O primeiro, ocorreu em 1995 e está relacionada a pesquisa que resultou na escrita da dissertação de mestrado da autora. E o segundo, em 2005, desta feita com a presença, também, de Moana Van de Beuque (pesquisadora) e Lucas Van de Beuque (fotógrafo), numa das viagens de pesquisa que resultou na escrita do livro Caminhos da Arte Popular: o vale do Jequitinhonha.

8 Trecho retirado de entrevista concedida à autora, durante o 25 FESTIVALE, realizado em Joaíma, Minas Gerais.

9 https://www.ufmg.br/espacodoconhecimento

10 Comentário de Ailton Krenak em entrevista a Roberta Souza, publicado em 17 de maio de 2020 no Diário do Nordeste online [https://diariodonordeste.verdesmares.com.br/verso/futuro-presente-a-natureza-ao-redor-esta-celebrando-nossa-parada-diz-o-escritor-ailton-krenak-1.2245965]

11 DAGLISH, Lalada. Noivas da seca. Editora Unesp, São Paulo, 2006.