Hidden Lives Revealing Hidden Lives in Pequeno África [Little Africa]: A Dialogue between Diego Zelota, Izabela Pucu, Thiago Haule and Sandro Rodrigues1

Sandro Rodrigues – I’m talking to you from the top of the Morro [Morro means hill and is also term used to describe favela communities as they were mostly built on hills surrounding the city]. Here in the picturesque neighborhood of Santo Cristo [Saint Christ] a port area in Rio de Janeiro. Santo what? São Cristovão [Saint Cristopher – another Rio neighborhood]? No, Santo Cristo! And where is that? It is actually next to São Cristovão, but they are totally different neighborhoods. Not to be mistaken, Santo Cristo is where the Novo Rio [New Rio] bus station is, you know? This whole surrounding region, right up to the viaduct of the Apoteose do samba [Sambadrome exhibition avenue for Rio Carnival Parades], including the morro where I am, all of this is part of the neighborhood. By the way, the morro has a name: Morro do Pinto [Pinto Hill]. The place “where nature becomes more beautiful”, according to a local samba.2 This confusion about location is recurrent when we talk about the neighborhood, because despite being one of the neighborhoods that make up so-called Pequeno África, this part of the region has been overlooked, it was not contemplated within the promised improvements that were to come with the revitalization of the port region [Pequeno África or Little Africa is a neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro’s port region encompassing various “morros” and historically home to Afro-Brazilian communities]. So you hardly ever hear about it, few people know about the existence of Santo Cristo. Yet, looking at it from another perspective, until now this anonymity has been something positive. In a way, it preserves certain characteristics and local aspects that only those who are willing to face the journey seeking knowledge of their city will be rewarded … After all, there is a living and pulsating city on this side of the tunnels, a world that remains hidden from most Cariocas [moniker for Rio locals]. For this, a little empathy is all that’s required.

Izabela Pucu – Yeah I know, I had the privilege of being taken by you and your daughter Marina for a walk on Morro do Pinto, where I had the chance to get to know a little of this incredible neighborhood, see viewpoints that messed up my orientation of city, and look closely at the place I only knew by name, from your reports, from your photos…

Sandro – And without a doubt, the best way to get to know a place is on foot. Those who just drive do not see the life that happens on the other side of the windowpane, at most they see just flashes. True I might be somewhat biased to talk about this subject, after all it is what has been building muscle in my legs walking up and down hills for the last 41 years. But it is this up and down, this close and intimate contact with the city that allows a strengthening of affective ties and the feeling of belonging to a place, whatever it may be. To walk about the Morro is to rediscover a city that is gradually disappearing, swallowed by new and controversial housing models. It is finding someone with his chair sitting on the sidewalk reading the newspaper or just “watching the world go by”. It is to appreciate the tiles printed with devotional saints on the houses. It is to say good morning “aunt” or, my “cousin”, as if passer-bys were all part of a big family! Problems exist, of course, as in any major city in the country, especially in its popular and peripheral neighborhoods. But despite this, we move on without forgetting the past, which left us everything we are and what we want to be. An old rap says that, “the best place in the city center is without a doubt Morro do Pinto”.3 I agree and second that! Ah, and so don’t confuse Santo Cristo with São Cristovão, ok?

Izabela – Yes … Morro do Pinto is in Santo Cristo and this can’t be forgotten! It’s interesting, because the three of you, each in your own time and in your own way, encountered or sought to encounter art. Do you think that this encounter with art has determined, made a difference or changed your relationship with the territory in which you live?

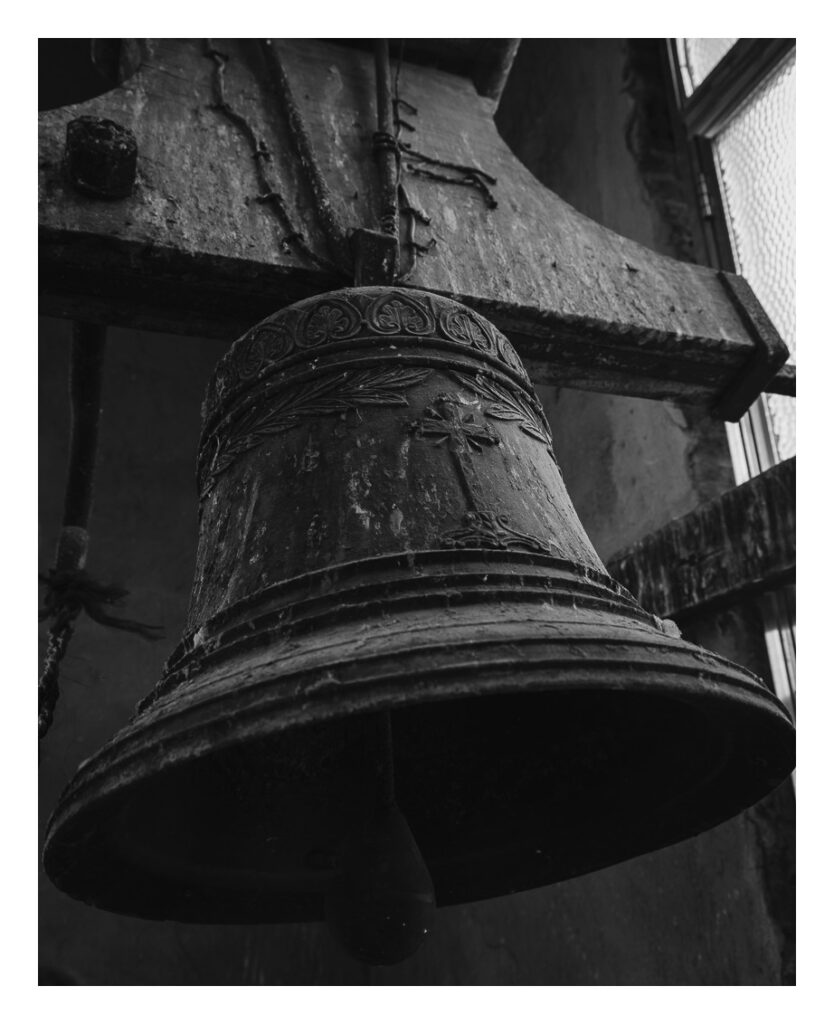

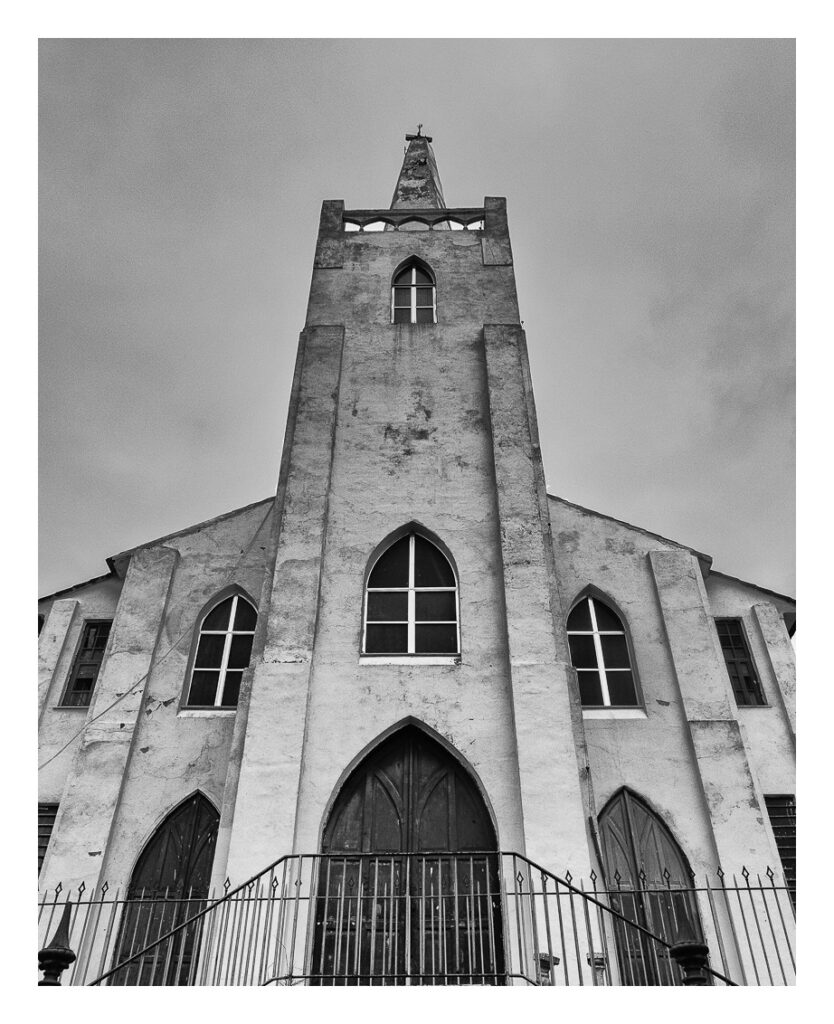

Sandro – I always liked photography a lot and I walk a lot, like I said. I walk a lot in the region, Saúde, Gamboa, [other Rio neighborhoods] Morro do Pinto and what often draws my attention is the homely, provincial, suburban air of the place. Architecture has always caught my attention, [and also] the steps that are everywhere here. When I graduated in history in 2009 I looked for a way to combine historical knowledge with my personal visual knowledge, that’s second nature to me. In my 41 years I know every cobblestone in this neighborhood. They are part of me, in fact … the railings, the balconies, the row houses, the saints on the facades, all of which greatly influences my artistic work, which is photography. Much of what I produce is due to my experience in the territory. This is what moves me, really affects me. Since I was little I liked to draw, to play the flute, every now and again I play … I already photographed with a very simple camera, but in 2014 for the first time I managed to buy relatively better equipment. So I thought I could do something with all that visual baggage that I had from the region, along with my training, to combine history and photography.

Izabela – And how did this desire to write about the territory begin?

Sandro – As an insider expert on the region, I realized that the Morro do Pinto where I live and was born, is a hill that in the port region almost nobody knows. We know the history of Morro da Conceição [Concession Hill] and Providência, but there is nothing about Pinto. I already looked and there isn’t anything. So I started to write, not a general, chronological history, although I intend to do something of that nature at some point, but rather, I preferred to write the history of Morro do Pinto focused on some of its landmarks, the places I know … It was this look at the territory that took me to photography, and from photography I started to write about the history of Morro do Pinto. I always believed a lot in what we call micro history, of the story told from certain places and from unknown people, because that was very well suited to the environment in which I live. And usually history books are not interested in facts that are not important on the national or world stage. But as a local resident, I decided to delve into these little things in the neighborhood, the stories we discover talking to residents here and there. It may not be of great value for official history but for the history of the territory I believe it has great value.

Izabela – Your gesture is so beautiful … there are people who go through these same row houses and see nothing special, or only see negative things, because there is a deprecation of the favela, erasing their cultural wealth played out every day in the media, by people in places of power, and it mustn’t be easy resisting it … having that open eye to see the poetry of people and things is really something very representative of what it means to be an artist, in my view… that look that changes the value of things and also this willingness to carry out a project just because of the simple desire to do it, for recognizing the importance of placing other narratives in the world, of revealing what is not normally seen.

Sandro – Yes, it is really a personal desire, but it also has to do with my training. Perhaps because if you are going to tell such a story, as Providência is the first favela, Morro do Pinto is forgotten, even though it is part of Pequeno África. Great names of samba lived here, rodas de samba [samba music sessions] were in full swing in the 1970s, the blocos [neighborhood block parties during Carnival] of the Morro won awards in the 1980s and but you can’t find any official histories on this, it is only in the minds and experience of the people here. So I thought I needed to look for this before people are no longer here and everything is lost. For example, it was on foot that in a pleasant surprise I discovered what was left of the foundation of the old Ponte dos Amores4 [Lovers Bridge], which from the time of the empire linked Morro do Pinto to that of Providência. Walking a few more meters, surprise! You arrive at Passarela do Samba! Few know, but this piece of street that is on the other side of the railway is the continuation of the famous Marquês de Sapucaí. No less important is to know that in the immediate vicinity Ernesto Nazareth, the King of Brazilian Tango, was born. Important little piece of info isn’t it? It was also nearby that the merchant Antônio Pinto Ferreira Morado lived, owner of land in that region, responsible for the opening of the first streets of the Morro in the 19th century and that consequently would bear his name. Going up the Pinto hillside, test the athlete for no fault, the city reveals itself at angles that few have ever seen, a master prize for those who get up there. Have you ever thought of having the Sambódromo [Sambadrome], Pão de Açúcar and Cristo Redentor [Sugar Loaf and Christ the Redeemer both famous landmarks to view the city of Rio] in the same frame? Or, turning 180 degrees, Maracanã [Football stadium], Penha Church, and Rio-Niterói Bridge? From above, this is possible. Even a newspaper from 1978 that I found in my research was right when it said that in opening up this space the morro could be a new “tourist attraction”, a lookout park. We just needed to let the tourists know. And if you want to “wet your whistle” after enjoying the landscape, how about one of those bars that still keep the year of its last renovation on its facade? It is very likely that you’ll find someone who will tell you a good story, the ones that make a place special.

Izabela – I see it as very important to recognize that each one of you produce your work while not depending on having a training as an artist, of having guaranteed the living conditions that would allow you to devote your time to that, to enter the hegemonic system of the arts … I see this gesture in the three of you, the choice for art as this affirmative poetic gesture, of existential emancipation in relation to the stereotypes about the place where you live, about what you can be or do. From what you say life in Morro do Pinto is itself a hidden life that you are trying to reveal. The story you tell has erasures, violence, but it has value, poetry, and beauty, it has cultural production. I think this is also in Diego and Thiago’s gesture of inscribing their work directly in the territory, [literally] on the walls of that territory, in dialogue with historical sites, such as Pedra do Sal [Salt Stone], a gesture that updates the symbolism of these landmarks in the midst of life that happens today in Pequeno África. One of affirmation when faced with disastrous government investments that have historically and continue today to not take into account the lives of these places, people, movements; everything is done from offices without real contact with the territory … I always see people walking along the viaduct coming out of the Santa Bárbara tunnel that passes between the Morros Pinto and Providência, even at risk of being run over. In other words, people needed this pathway in the past and still need it as it takes them more directly to the region of Praça 11 [Town Square 11] and the subway. And the viaduct also made the connection between the two Morros precarious. This division seems to me to have been part of something symbolic, relegating Morro do Pinto to oblivion in official history.

Sandro – Yes, it is true. This path between the two Morros is really quite old. If I’m not mistaken it was called the Saco do Alferes path, which was the name of that region where the Santo Cristo Church is located. I saw this path in an 18th century print. When I wrote about the Ponte dos amores, which connected Providência and Pinto, I also identified other aspects that contributed to this separation. Many residents of the region think that Morro do Pinto is a place for people who have money and are prejudiced against people here, because it’s really different from the other hills. Unlike other favelas in the region that grew according to the disorderly image that one has of the favelas, because people build and install themselves wherever they can, Morro do Pinto has paved streets from top to bottom, as I said earlier. It is a geographical difference, but here it is [just as much] an area of popular occupation like the others. A lot of people say that here it is like Santa Teresa, [a bohemian Rio neighborhood] that mixes popular occupations and rich people side by side. You know that at some point in my research I saw a document, an old map where it appears that this area was called Santa Teresa in the 18th century? It is a story that I need to delve into more, this document is in Portugal, but it does have some connection.

Izabela – And you Diego? How do you see this encounter with art as something that transforms or defines your relationship with the territory? From your first work to your current wall mural for Rua Walls5 that you and Thiago are painting, can you talk about your journey?

Diego Zelota – I studied at Adro, a Franciscan public school here in the region, which is more difficult to get into, but I ended up there because my mother wanted me to go there. I had wanted to study Licínio Cardoso, where the cream of the neighborhood went, everyone I knew, the guys I hung out with, still know and live with. The Franciscan school had a different indoctrination, I had to sing the national anthem, study to get in, and there was no messing around as in other schools. But what stuck with me at that school was the question of art. I had a very nice art teacher, I am still in touch with him today, Eduardo, but I always called him “queridão” [querido (masculine) / querida (feminine) literally means dear or dear one, an informal term of endearment common in everyday speech; often suffixes of a diminutive “inho” or aggrandizing “ão” nature are added “queridinho” or “queridão”]. He married a student, lives here in the region, and always stops by to give me a hug. He encouraged me a lot. He was a super cool guy and I think he would never have imagined that Diego de Deus da Conceição, the troublemaker of the class, a holy terror, was going to get as involved with art as I ended up doing.

Izabela – Here again, the exercise of art as this tool to break those limits, these stereotypes… art as a form of education that emancipates…

Diego – Yes, to feel like you own the territory… There are other people who encouraged me, among them Eron, who is perhaps the most important reference I have. In addition to being a teacher, Eron is my friend, he was my tutor for a long time and he is the caretaker of the main chapel here in Morro da Providência. He is a great, a great talker, he loves to talk and I love to listen to Eron because he has a rich experience and knowledge of Providence, where he always lived, much more so than me. Eron is a great encyclopedia of history. Sandro has also been close to him. He once suggested that I was his successor, a griot [traditional storyteller] as he says.6 With Eron I learned a lot about Providence, about the divisions in that territory, about Pedra Lisa [Smooth Stone] that many people don’t even know is a part of Providence, about how people from different communities related with one another, about conflicts, because the Morro doesn’t belong to just one group… he was undoubtedly someone who got me involved with the question of art, with this desire to study, to know, to want to know more about my territory, to do research. This has a lot to do with the mural I’m going to do on Rua Walls [Walls Street]. It will honor two people: a great leader of the resistance of the union of the ushers, the longshoreman and sambista Aniceto, that many longshoremen do not know, and Cláudio Camunguelo, sambista and longshoreman who hung out here when samba all the rage in this area, it was Thiago who introduced me. I am the son of a longshoreman. Most of the longshore workers live here in Providência and don’t know these guys.

Izabela – Yes their story relates samba to longshore work and the port region… Do you know what is lovely to notice as I listen to you? It is that you lead lives that have been hidden to an extent that are now potentially in visibility, but that are always concerned with revealing the hidden lives in your territory. You could do anything, but you chose to do this via your lives and your work.

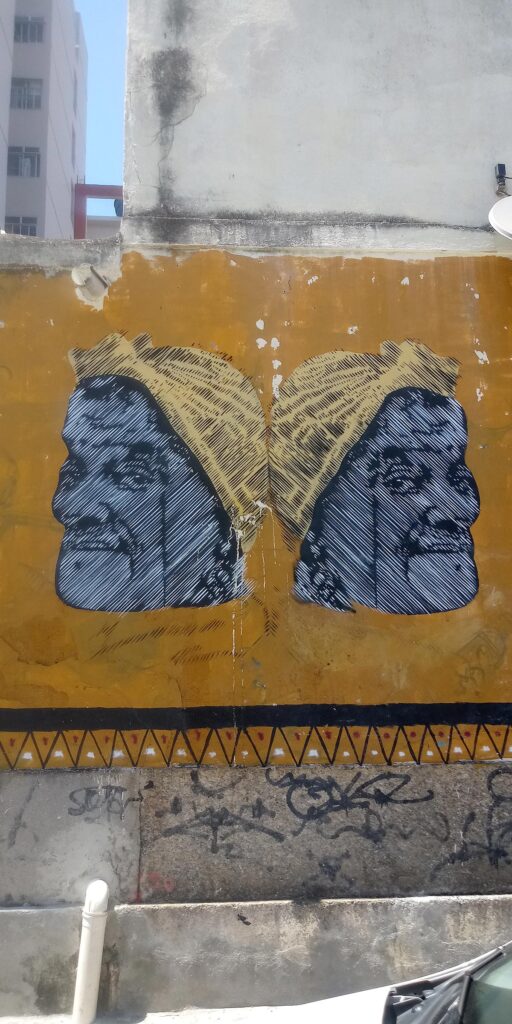

Diego – I think it has to do with being an artist, but I always felt like I owned this territory. I come from pixação [a form of graffiti using signatures and symbols] and at the beginning it was just that, to assert myself, to say – I am here, this is my signature, my form of expression. Then I grew up and changed my outlook somewhat, but never losing this perspective, never forgetting to bring to the fore the history of my territory, stories that we have to tell if we are not to remain invisible.

Izabela – There is a game between pixação and graffiti, one of visibility and invisibility in which you dislocate your position in this territory. You and Thiago, who was not a pixador himself, but who also flirted with graffiti when he was a boy, and in a certain way also informs Sandro, as his research explores other spaces. Because even if the pixo is a signature, the understanding of that signature is restricted to a community of pixadores that, in a way, address each other. So even if it is a signature, it is more anonymous, lost in the flow of the city. Graffiti, however, seems different; it is more public, striving to engage everyone who passes by its walls. Graffiti has a signature, a recognizable brand, it is often associated with projects revitalizing an area that has institutions involved, in short, an edict that it is not that of pixação. And today you paint on canvas, photograph…

Diego – I never got too involved with groups of pixadores, of urban art. When I did pixação I did it alone. What excited me was to pixar in high places. It was complicated to get there and I got there and left my mark. This was what excited me. Maybe I have been influenced by my past of being a pixador, but even when I started to do graffiti I wanted to remain obscure. I don’t sign anything on the street, Thiago knows. I have a project that I did on the wall of a bar in Pedra do Sal that nobody knows is mine and it became an emblematic mural there. People photograph themselves in front of the work that features three women with afro hairstyles with the phrase “curly is beautiful, ugly is your prejudice”. It was a series of images of women with strong expressions, sporting afros. When I did no one went afro, they all generally straightened their hair. Now the work is being read from another angle, both that of the empowerment of black women and representing the resistance of that place. The other day I saw a documentary that started with the image of my work. People say that I should ask for copyright … but I was satisfied because for me it means that it worked.

Actually, I really got to know graffiti in an exhibition at Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil [Bank of Brazil Cultural Center known as CCBB] called Fabulous Disorders in 2007.

Izabela – This is curious, that you got to know graffiti from an exhibition and not the street…

Diego – I had already seen it before of course, but I suppose here was the first time I realized that graffiti was a form of expression, of art and from there on I began to get involved more in graffiti, to get to know its languages. To tell the truth at the beginning I had a lot of preconceptions about graffiti – Graffiti wasn’t something for a guy from the favela!

Sandro – It was something for playboys! Did they call you a playboy?

Izabela – How strange, because generally speaking, or rather from my cultural and social perspective, graffiti is very much associated with the peripheries, with favelas.

Thiago Haule – I think that it’s also an economic question, art material is expensive, it’s expensive to sustain yourself in art whether a hobby or profession. If you buy 4 cans of paint you’ve already spent R$100 and that’s hard. It’s true that the origins of graffiti are underground, marginal even, coming from Brooklyn and the subways in New York… but here in Brazil it’s something that became mainstream when it started being done by those come from art schools, by designers, white folk, middle class or rich people, with a university education…

Izabela – Ah, yes, I see.

Diego – So this was one of the reasons that I chose to work with stencils, as it’s faster and more practical. We can’t always be standing there on the street for a long time and when you don’t have much money to buy materials, the stencil gives you the possibility to communicate something faster. And this made me fall in love with it, as well as living in the city center. Here I meet a lot of people, a lot of great people have come through this area and taught me a lot. Thiago and I did two workshops at Casa Amarela, which at the time was coordinated by an artist here from Providência, Maurício Hora, who is a strong influence for me. One of the workshops was with Mônica Nador, who is an artist who works with stencils and we learned a lot from her. And then with Vhils, a Portuguese artist, a very cool guy who is a reference in street art, and who was also important for our work. I am a ghost of Casa Amarela, I stayed there for a while, I felt like I owned that place … I always felt that the community needed an art space, where children could have contact with the making, culture, with free painting, with the stencil … and I was very happy during the time I was there. What I did was bring the guys, the children, the people who know me, and in a way they see me as a different being, who identify with my lifestyle, with my bike craze and with the graphics … I think when these people see me they think: this is for me too!

Sandro – Many artists here took these courses at Casa Amarela, but only Thiago and Diego continued. I did it myself, I was the precursor, the first to enroll in the course but I didn’t continue.

Thiago – And all of this, this kind of training was via the favela, nothing to do with the government, with the revitalization of the Porto do Maravilha [Port of Wonder – name given to the revitalization of the port region in Rio by the administration of then mayor Eduardo Pães]… it was a training that we had that came via the favela, by our own means.

Izabela – And you use very intricate stencils, what you do is very complex.

Thiago – Not at all! There are artists who use stencil who are really ace at it … we still have a lot of improve! What happens is that we do things when we can, in between the rushing around of everyday… and all work needs time to reach perfection. If we had support and time there would be no limit. This work we are doing at Rua Walls is a great technical challenge as well, not just because of the scale, which is huge. In general, I work on the wall to the actual size of people, sometimes a little bigger, as in the portrait of Tia Lucia [Aunt Lucia]7, where her face was enlarged. But also because to cover that whole area in halftone, which is a technique in which the drawing is all composed of lines, it is painful, the arm movement is very intense … but it is also a very pleasurable process! What I think is that I can’t do this work based only on technique. There are a lot of artists embellishing the city with beautiful images, with very interesting works and that I respect a lot; but I don’t want to do this, at least I don’t want to do just that. I want to question things with my work. That is why I paint the fury of black warriors, the faces of indigenous peoples, the flag of Pan Africanism, as I am doing on Rua Walls mural. I need to put the conflicts related to my origin around the city, declare my love for the Morro where I came from. I work to put all this up for debate in the flow and rush of the city. The image is the way I find to translate my critical thinking, just as Sandro found photography and writing.

Izabela – And where do these references that you use in your work come from Thiago?

Thiago – It comes from research, from texts by Brazilian and foreign teachers that life has brought me… this formed the basis, but it also comes from research on the kingdom of Kemet, which is another way of naming and understanding Ancient Egypt, a refusal of this idea of Egypt built by the Greeks and which has to do with the origins of the African diaspora. It comes from these surveys on indigenous peoples and on Pan Africanism. My main research reference, in fact, is my brother. When he graduated in history I followed everything, he taught me how to do more research on a topic that was interesting to me. My brother is my main research reference, in fact for many things. And basically I thought about making art because since I was a kid I really liked watching a program called “O Mundo da Arte” [The World of Art].8 That system, that way of thinking about life, of creation, whether painting, sculpting fascinated me. There I saw a lot, I met artists like Amílcar de Castro, Carlos Fajardo and many others.

Izabela – From my perspective, someone who comes from a more formal education, your remarks here point to a radical inversion regarding the ways in which we produce knowledge, suggesting other ways of thinking about education and forms of training, especially in peripheral areas, in favelas. The other day I watched a live with Raul Santiago, an entrepreneur and human rights activist from the favela Complexo do Alemão, and I was amazed to learn about his journey, what he had been doing prior to his emancipation. He said that it all started with a group of friends who frequented a Lan house, which was the main space where they hung out, got their information, sociability, and leisure that was due to close; so they had an “orkut fest” [Orkut party – Orkut was an online platform similar to Facebook] and from then on this movement unfolded in a series of actions aimed at making things they wanted to happen in their territory, such as the actions mobilized by you all. For him, this process made him see relationships with people as central to his emancipation and learning process. The guy is a social scientist, an absolutely shrewd manager, he is inventing, along with his companions, cutting edge social technologies, communication, management, teaching this to many people, and at no time does he talk about the university or books, at the most TED talks. It is this generation, people like him, like yourselves that make your own inclusive worlds, that you do it for yourself, where the greatest transformative potential of the societies in which we live are. This is increasingly clear!

Diego – It’s true, I draw on outside references, but most of the things I have learned here, all started here. Even graffiti, you know, because I looked for outside references, but my cousin Paulinho, for example, at the time of the world cup, he graffitied the whole street! There was always a gang here painting things on the wall. This could also be considered graffiti.

Izabela – That’s right! I never made this association between these paintings and graffiti … on the street where I spent my childhood, this was also done directly on neighborhood streets, and we got used to living with those drawings even after world cup. This was a very common practice until the 1990s, which not seen so much today … it practice of horizontal graphite drawing made on asphalt.

Diego – Yes, these are influences here from the hill, from a past that we draw on. Working at the Museum of Art of Rio also gave me an awakening. Even though my work there was administrative, being there helped me get an understanding of the professional field, about what to do with my art, that one could making a living working with art. I had been doing art as a hobby, to convey an idea, to be with people I identified with … to leave Providência and go to work with guys in Morro do Pinto, who were involved in a cultural, social movement, the collective I ♥ MP … this type of organization I had no contact with here in Providência so I started bringing everything I knew outside into the favela, and some guys here started looking for me, as for example the people from Roda Cultural Central9 [Rap and Hip Hop sessions] who had seen the Roda Cultural of Morro do Pinto and loved it.

Izabela – I saw on Instagram the photos you took of the Roda Cultural Central, I really liked it. We even exchanged some messages at the time. What was that got you started in photography?

Diego – I still haven’t presented my photography to the world, I show a few clicks … maybe all of this will only be valuable when I’m really old … but what I photograph are things that are in constant motion. I photograph today and tomorrow I photograph something else, and, in a way, photography is a way of accompanying the change in this scenario, a futuristic photograph. And there is a lot that is disappearing, like the culture of the roller cart … the festas juninhas [June parties with folk costumes, music, dances, festivities] … here in Providência there was a very strong festa juninha party culture, it was something that mobilized people for a long time, I photographed it .. .and now it’s not happening anymore. I started shooting with Maurício Hora, I didn’t understand anything. And everything is a matter of understanding. And I saw a guy in the middle of the night, with no light at all, standing on a ladder photographing. You’re crazy? There is no light there, what are you doing? I asked, and he told me he was taking a long exposure photograph, which is the kind of photography I like to do. I really enjoy working with long exposure, sitting in the midst and waiting to see how long those things around you will come together and give that boom of the image.

Izabela – Thiago, Sandro, and how did I ♥ MP come about?

Sandro – Thiago did the first activity in 2011.

Thiago – The collective I ♥ MP started in 2011, but I go back even further to 2007 and the beginning of the collective Topinheco 07. Topin is Pinto with the syllables in reverse and Nheco was one of the old names of Morro Pinto, Morro do Nheco. This collective was already a movement of friends, we occupied part of a carnival bloco Independentes do Morro do Pinto [Independents of Morro do Pinto] based at the top of the hill. We were younger, each of us already initiated in the day-to-day craziness, trying to find themselves, find their way, but we tried to restructure the place and create cultural actions. In time things fizzled out and it ended. The name of the collective I ♥ MP is a parody of the brand I ♥ NY, which we were seeing everywhere, on caps, stickers and it had nothing to do with us. I later got to know New York and I really liked it, but at the time I didn’t know it. The first action of I ♥ MP in 2011 was the painting of the phrase I ♥ MP on a wall on Rua Santo Cristo facing Rua Sara, near the old Behing factory. I painted it and didn’t tell anyone. Then the crowd started talking: – Did you see what they painted down there? Damn, cool, I ♥ MP! When some of our closest friends came together and I said I had painted that phrase then the ideas started to emerge. And from then on we began to move together as a group promoting cultural activities. Great friends, and other people got together, like Diego, each with their own specifics, wanting to add and carry out the work that we had always thought of doing.

Sandro – And it was also a response to the revitalization of the port region that was beginning to happen. This revitalization never arrived for us, so we weighed it up: If the revitalization does not come here then we will start to act, we will do our own revitalization. And that motivated us to create and do, to go out painting, to put music on the street … we managed to make it happen and continue to today. The official “revitalization” would reach Praça Mauá [Mauá Square], at the most as far as the beginning of the Rua Sacadura Cabral; it was never going to reach here. As it never came we did a rap session at the top of the hill, and did everything on our steam, with the money in each person’s pocket, we could get a can of paint here, something else there … that’s how we go on…

Thiago – Yes … we used to make a piggy bank, spend a few months doing nothing to save money, get consigned beer, sell beer, make stickers and in this way get money to carry out the events and the paintings.

Sandro – It’s through this that we met Diego.

Izabela – Guys, it’s really impressive the way that being an artist for you comes close to this feeling of wanting to do something for your territory. It is difficult to even identify what comes first, because just as art was something that served to awaken your gaze to the power and beauty of your origin and place, living in that place also formed you for art. It is so beautiful … it gives so much meaning to the artist’s place in society … it is another perspective, or it is still a critical rescue of a perspective that is at the origin of art, which is pre-modern, which has nothing to do with the idea of an art whose autonomy would be to withdraw from the social fabric and place itself on a pedestal. In the case of your work, being an artist involves not only doing a job, but also creating the structures where it will circulate and creating the conditions so that other people can also be artists or have contact with art and from that change their relationship with its place and its origin. This gives another meaning to the idea of an artist, of art, this places art as a manifestation of the political order, much more strongly than simply addressing, or representing a theme or a political issue. You guys are awesome…! And how did you hear about them Diego?

Diego – We already shared some ideas, and in a way, I was always looking for people from the art field, a group that wanted to make it happen where we live, to awaken this love for the place. I sincerely like to live in Morro da Providência, even though I grew up with that thought that your life only gets better after you leave the favela. I lost my father very early, and my mother is very different from me, she was always very afraid, she always wanted to keep me at home because of this bad image of the favela, the shootings. It took her a while to understand my lifestyle. I am happy to be able to take care of my son here. I can leave my house and leave the door open and no one will steal anything. I like it here, I am pleased and thankful for the experiences I had here. Art, photography, helped me to see the beautiful side of everything. And I want to return it.

Sandro – And I think that these guerrilla actions have borne fruit, and continue to do so. We see in various places in Morro do Pinto the inscription I ♥ MP and many of them were not made by us. These people are declaring their love for Morro do Pinto! People were touched. So much so that when we did things, someone always would come up and say: I paint at home, what a cool job! Did you do it? These collective actions spurred people’s desire to have a closer contact with art, to see cool work on their wall. And that created a sense of belonging for them.

Diego – There were people who asked if we taught this, who said: – My son wants to learn this! Who wanted to know where we were …

Sandro – We even did a graffiti class and a large group of kids came. It was a way of saying that there were many things here, if you think it is a favela and because of that there is nothing here, you are wrong. There are people here who can create something amazing, sensational!

Izabela – The favela has historically been a place of potential and you are affirming this within the favela with your work and way of life. With this, you are, at the same time, affirming your potential and opening up the possibility for people to change their conceptions about their place of origin, about themselves. That is to make of art a counter-narrative, an instrument of emancipation.

Sandro – We never made a lot of money from it, in fact most of the time, I ended up spending money. So it’s really a genuine desire…

Diego – I learn a lot from Thiago … and he always says that I don’t know how to put a price on my work, that I don’t value myself as an artist. I understand what he is saying and I am maturing accordingly. But I am happy when I sell something to someone who lives where I live. Who has the same experiences that I have. And selling cheap gives me the opportunity to sell a work to someone just like me, someone from my territory. I want to revere people just like me, people from my territory. This makes me happy.

***

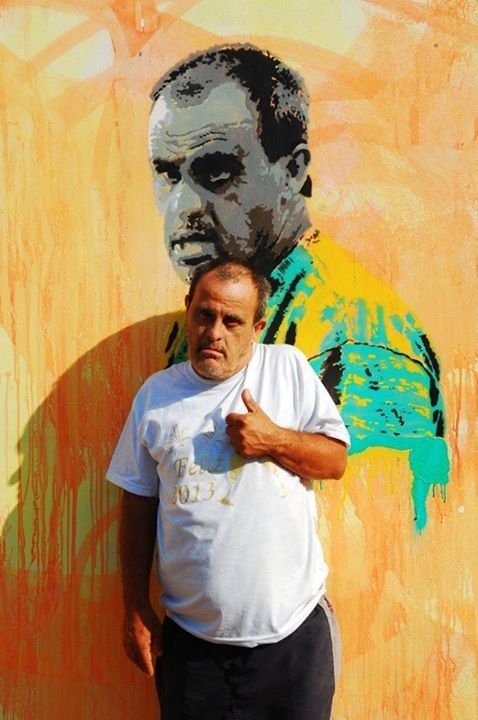

Diego Zelota

Visual artist and photographer. Curious, he travels throughout the city to explore different worlds and incorporates these references into his work while always affirming that he is from Morro da Providência.

Izabela Pucu

Curator, researcher, professor, cultural editor, and manager. She has a doctorate in Art History and Criticism from the Universidade Federal de Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). She has edited various books, curated exhibitions, conducted research and other projects both independently and within institutions. She was awarded Jabuti prize in 2020.

Sandro Rodrigues

Has an undergraduate degree in history and is a self-taught photographer. He is always traveling between places and deploying documentary photography. Since 2017 he has been registering his neighborhood of Santo Cristo in the port region of Rio de Janeiro, its traditions and people.

Thiago “Haule” Rodrigues

Photographer and self-taught visual artist. He creates narratives drawing on images and material from where he lives, articulating references with Pan Africanism and the struggles of indigenous peoples, to highlight the social inequalities of our time.

1 This dialogue was produced via a virtual meeting on zoom, August 26th, 2020, during the Covid 19 pandemic. The conversation lasted about 2.5 hours and was transcribed and edited by Izabela Pucu, who also edited the footnotes. Sandro Rodrigues directly wrote some paragraphs attributed to him, in particular the most poetic passages about Morro do Pinto, and Thiago Haule complemented some questions via audio messages on whatsapp on September 15, 2020, all of which have been edited as part of the final text.

2 The origin of the samba in unknown but the expression Sandro…

3 A clip of the rap “Barroso e Morro do Pinto” by Adal and Pica Pau is available on youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-cz9fdz0C6c.

4 See the text “A ponte dos amores” written by Sandro Rodrigues and published on 28/03/2019 on the Collective I ♥ MP facebook page. Avaiable in Portuguese: https://www.facebook.com/notes/coletivo-mp/a-ponte-dos-amores/2127664477326172

5 Rua Walls [Walls Street] is a project comprising various actions among them: an occupation with large graffitied imagery on the old storage barns on Rodrigues Alves Avenue in the Port Region in Rio de Janeiro. The following artists participate: Agrade Camís, Amorinha, Bruno Lyfe, Célio, Chica Capeto, Diego Zelota, Doloroes Esos, Flora, Yumi, Igor SRC, Leandro Assis, Luna Bastos, Mariê Balbinot, Marlon Muk, Miguel Afa, Paula Cruz, Thiago Haule, Vinicius Mesquita and Ziza. The project involves a series of social and cultural actions in the region. For more information see: https://www.ruawalls.com/

6 Griot (also written griô or the feminine form griote) is an individual in African tradition whose vocation is to preserve and transmit the histories, knowledges, songs, and myths of their people.

7 Lucia Maria dos Santos, known as Tia Lúcia, was a resident of Morro do Pinto and icon of the Port Region, who died in September 2018.

8 The program “O Mundo da Arte” [World of Art] was broadcast on STV, the old network of Rede Sesc/Senac de Televisão (today SescTV) in 2000. Between 2005 and 2007, the program was also broadcast on TVE Brasil.

9 Roda Cultural Central comprises competitive rap sessions with poets and rappers. Started by young people in Morro da Providência on Wednesday evenings behind the station Central do Brasil.