Ethical-Aesthetic-Political Agency in Reparations for the Damage Caused by State Violence

Tania Kolker

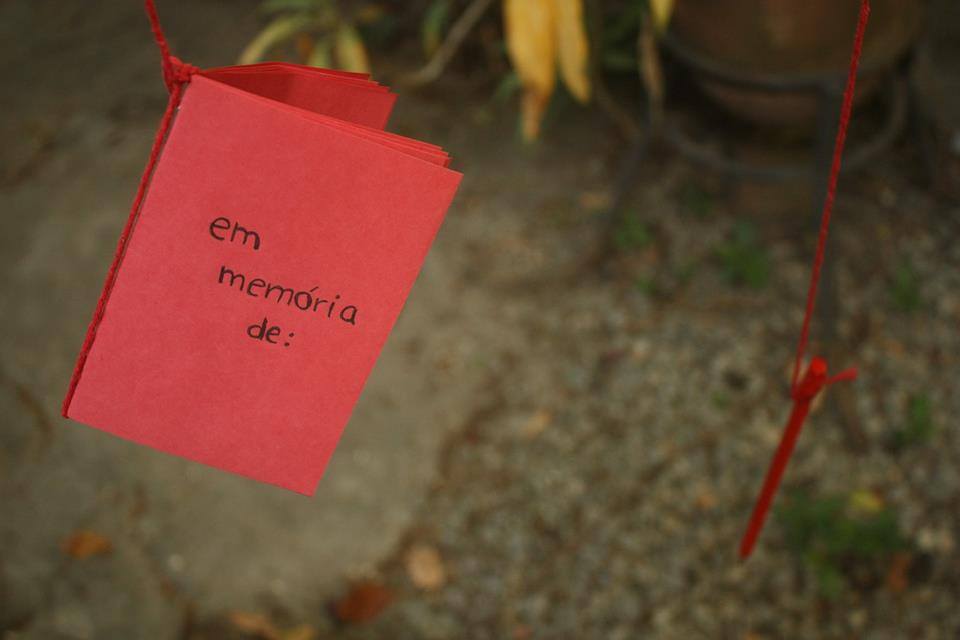

To Estrella Bohadana who destroyed by torture reinvented her life in the encounter with dance and philosophy.

To Paulinho Fontelles Filho, who was born in prison and carved out a life in struggle and poetry.

Time 1: The Clinical Testimony Project and Advances and Setbacks in Brazilian Reparation Policy

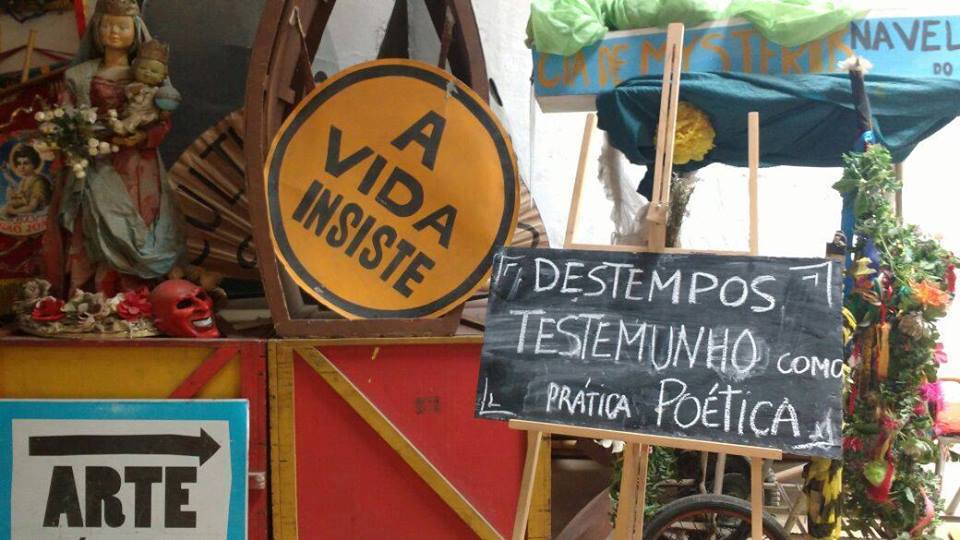

What can I say about an event where the possibility of making sense of experiences that have been silenced for so long remakes the ties between words and the world and restores the ability to establish new worlds? How can we illuminate this moment where past and future come together opening up another field of possibilities? How to give language to what started another temporality, a yet-to-come? I asked myself these questions as I wrote about the exhibition/event Destempos: Testemunho como prática poética [Out of Time: Witnessing as a Poetic Practice].” Facilitating an encounter between artistic, political, and clinical practices had long been a proposal desired by everyone who participated in the Clinical Testimony Project. But, when it started to take shape, the Project was already coming to an end, without any prospect of renewal.

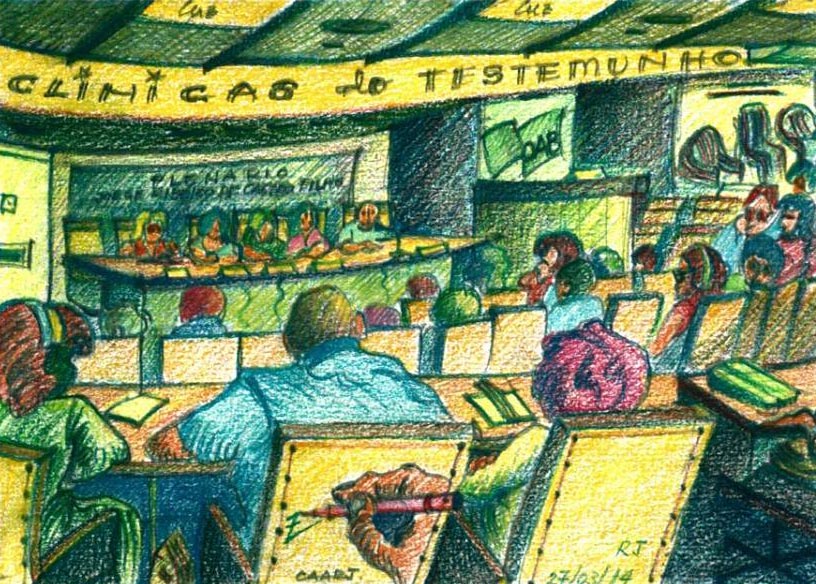

In 2013, the Brazilian State initiated a pilot project for the psychological reparations of those affected by the civil-military dictatorship. Developed by the Amnesty Commission – official organ linked to the Ministry of Justice –, the objective of the Clinical Testimonial Project was to guarantee psychological care and to determine subsidies with the goal of developing public policy aimed at caring for those affected by state violence. Prior to that point, although the Brazilian State had already recognized violations and paid for some reparations, the reparatory model itself had contributed to generating silence and resentment. Previously reparations had been administered via bureaucratic channels where only the violations against those who had been given amnesty for political reasons had been recognized. This exclusionary policy meant that the regime’s repressive actions against the most impoverished sectors of the population remained invisible and prevented society as a whole as perceiving itself as affected, deepening the isolation of those who had been politically persecuted. This model only began to change in 2007, when the Amnesty Commission, under the presidency of Paulo Abrão, expanded the scope of reparations, implementing the Clinical Testimony Project and creating Psychological Reparation Study Centers (CERPs) with a view to extending this right to others similarly affected and instituting some symbolic measures aimed at the rest of society.1 In addition to these measures, the Commission began to examine requests for amnesty in public sessions (often in the very places where the violations occurred), including the testimony of those that had been persecuted politically and to hear apologies from the state as part of these rites of reparations. They also began to support memory projects in partnership with civil society and universities. This work continued up until the challenges to the democratic rule of law following the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff in 2016.

At the time, on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the 1964 civil-military coup, the country had been experiencing an intensification of disputes over the meaning of the events. On the one hand, the Federal Supreme Court had maintained the extension of amnesty to torturers and, on the other hand, the Inter-American Court had condemned the Brazilian State for the deaths and disappearances in Araguaia, forcing it to review the Amnesty Law and to guarantee psychological attention to family members. At the same time, President Dilma instituted the National Truth Commission, which despite having received severe criticism, both from those affected by the repression and from those interested in denying it, its simple existence contributed to the creation of hundreds of state, municipal, and sectorial commissions and triggered the realization of numerous political, academic, artistic, and psychoanalytical activities that made it possible to bring together those that had been persecuted politically and their family members who had never spoken about the tortures they had suffered. The fact that these reports became more readily accessible and that, finally, there was a public recognition of the violations, began to guarantee the conditions that could foster a new relationship with the past.

It was in this context that we started the activities of the Clinical Testimony Project, offering a clinical apparatus for the realization of public testimonies. The project assumed the ethical and challenging imperative: to enable victims and others to leave silence behind; to find ways to narrate what happened; and to contribute to clarifying cases and recovering the collective dimension of these historical events. How to remember what was necessary to forget to continue living? How to put into words the very witnessing of the power that is meant to keep one silent? According to a vast literature, it is impossible to narrate trauma. Yet at the same time, denouncing torture is a fundamental step in the fight for justice and reparations.

If for those directly affected it was difficult to narrate the violations suffered in their own flesh, for those who lived the terror in childhood, or inherited the marks of this painful legacy from their forbearers, the difficulties seemed even more insurmountable, affective stains, not only unspeakable, but unthinkable. How, then, to give language to these experiences if we are talking about something that could not be forgotten, but also could not be remembered? Answers did not take long to appear.

At that time, what was at stake was the possibility of “becoming-witness” and not that of presenting a factual account of torture. Considering the productive dimension of language and understanding testimony as a performative act that sheds light on what happened and triggers new processes of subjectivation, what we were seeking was the opportunity to access what had been suspended in time and had no place in history. These truly autopoietic moments, in which testimonies impact both what is possible to see and say, as well as the power of self-production, are moments in which life can branch out and leave behind subjective modalities trapped in the past, rehearsing new ways of experiencing life.2

Over the course of four years, the Clinical Testimony Project contributed to the reparation of the psychological suffering caused by torture, as well as to furthering the impact of such processes in society by supporting opportunities to listen to testimonies and offering therapeutic resources for the collective elaboration of terror.3 However, 53 years after the 1964 coup, with violations documented by more than a hundred Truth Commissions, Brazil was once again experiencing a further challenge to its democracy. In this new scenario, in which resources for human rights programs began to be suspended and public declarations in favor of torture and torturers became frequent, the Project that should have been transformed into public policy was to be terminated. So, as 2017 came to close, with the willingness of the Project participants to fight for this process, we felt called upon to continue. The setbacks in reparatory policies were discussed in therapeutic spaces; the position was defended that these policies should reach all those affected by the violence of the state, past and present; partnerships with other collectives in the struggle for memory, truth, and justice intensified and proposals for debates as well as clinical-political-poetic activities emerged.

Time 2: Looking for Intercessors to Give Language to an Event

What we were going to narrate would reopen drawers that memory had suppressed, enabling communication between worlds long kept apart, restoring bonds of trust and triggering new possibilities. It is said of traumas caused by torture perpetrated by dictatorial states, that, due to the lack of social recognition, they return, like lost souls, without ties to the present, without being able to become past, nor as an experience to base future actions. Dragged throughout life as if a foreign body, on the one hand, they remain dissociated and immune to the passage of time and, on the other, they insinuate themselves through all the gaps, being the cause of incessant repetitions. In turn, forced into silence and to face these marks alone, people affected by such violations resort to the mechanism of repetition as a way to dominate them. As if in order to get out of a passive position, their only recourse is to reproduce the shock indefinitely, that, in so doing, normalizes the trauma, losing its intensity.

However, what might be apprehended only from the perspective of its negative character of being imprisoned in the past may also be interpreted as an attempt to recover the capacity to act that torture strives to liquidate. As the aim of such violations is to destroy all forms of resistance to power and to hide the traces and evidence of this destruction, the unconscious obstinacy in repetition could not fail to have an element of struggle against forced forgetfulness. As psychologist Francisco Ortega notes, in its quality of event denied by reality and public memory as yet to be realized, what cannot be remembered, but cannot be forgotten, will always participate, even without knowing it, in the struggle of “clarifying meanings, defending or challenging memories, legacies that operate silently.”4

Although trauma studies tend to highlight the individual dimension of compulsive repetition, it is worth remembering that this mechanism, although apparently closed in upon itself, actually requires the interaction of the person’s surroundings in order to be carried out. Although this mechanism fixes subjects in reactive modes, making them transmitters of a legacy of horror, it also makes them bet over and over that, at any moment, it might lead to unprecedented paths. In view of the processual nature of subjectivities and the open character of events, it is in the present and through agency with the world that trauma may find resolution and the rejected elements of the past can take on new meanings.

In addition, considering that for representationist conceptions of language it is impossible to narrate trauma, such events via their sensorial and experiential aspect may open up other perspectives for psychic processing. However, for those who have gone through extreme situations and had their existence divided into a before and after, it is not enough that these events just produce sensations. As what happened broke with the continuity of the subject’s existence and the vision of him/herself and others, the connection with the world has to be reinvented. For language to account for the creation of new meanings, the extra linguistic and non-linguistic components of the event must be considered.5 The contrary is condemnation to incommunicability and the eternal presentification of the traumatic.

As it is not possible to produce subjective changes solitarily, it makes all the difference if such events occur in isolation or when organized in collectives. In the latter case, participation in struggles for justice and reparation, in addition to sustaining the connection with the world, is always an opportunity for life to continue inventing itself. As Cecília Coimbra noted, at the time, as President of Grupo Tortura Nunca Mais / RJ [Torture Never Again, Rio de Janeiro]:

Denunciation, a making public, removes us from the territory of secrecy, hiding, from the private. With that, we leave the place of a weakened, depotentialized victim and occupy that of resistance, of struggle, of those who come to realize that their case is not an isolated event; it is contextualized, [seen as] part of others and its denunciation, clarification, and punishment of those responsible opens the way and strengthens new denunciations, new investigations. In affirming the collective dimension of this path we have the possibility to start to address impunity; to show that the so-called norm – where punishments never happen – can be changed, can be reversed. […] Publicizing, bringing it out into the open, collectivizing, and politicizing the struggle for reparations for damage suffered, therefore, has been an important path for those directly and indirectly affected by state violence.6

In other words, the more you deny what happened, the greater your ability to imprison the present. Here, this safeguarding cleavage mechanism, instead of protecting, can lead to deadly functioning, operating like time capsules, capable of bursting forth at any moment and reactivating terror or remaining dormant to be transmitted to subsequent generations. Used as a means of affective shielding, this mechanism can also produce a type of subjectivity aimed at preventing something from happening, compromising the possibilities of re-creating life. It is as if, in the face of fear of suffering again, life itself becomes threatening. Not being able to withstand being crossed by forces that one cannot control, encounters and their potential to produce otherness are avoided.7 No longer any need for prison bars and jailers, life closes in on itself.

However, in addition to pure repetition and political struggle, there are other ways of bringing to light what could not be integrated into individual or collective experience via the support of clinical apparatuses, forms of witnessing, or art. However, as the real target of terror is the potential of struggle itself, the fate of the trauma will depend on how the state and society respond to what has happened.8 Being treated as worthless by state agents can be annihilating, but not necessarily strong enough to consolidate destruction. If this trauma is followed by a response from the state and society that denies the legitimacy of torture, the feeling of belonging of the affected person is not affected and the struggle preserves its meaning. But when the state and society act as if nothing has happened, the bonds that link the sufferer to others are deeply shaken. According to psychologist Erik Erikson, “The I continues to exist, even though it has suffered damage and even permanent changes; the you continues to exist, albeit distant, and can be difficult to relate to; but the we ceases to exist.”9

In a similar manner, destinies of trauma reflect how psychological apparatuses have dealt with it. In this case, clinical approaches in the service of the production of internalized subjectivities and focused on children’s history, to the detriment of the external reality, tend to intensify the split between the individual and the collective and to reinforce the difficulties of acting in the present.10 Clinical interventions that consider the inseparability between the clinical and political and between individual and collective memory contribute to the symbolic repair of the damage and help to produce turning points in the ways of life dominated by deadly repetitions. In line with this last perspective, but supported by Nietzsche to escape what he calls a historical disease, the psychologist Cristina Rauter reminds us that we must settle the score with the past, but without neglecting opening up to the new. Seeking intercessors in art and philosophy and concluding that there is no way to erase the marks of time, only that of producing new meanings by way of the event, Rauter urges us to look for other ways to access the marks of traumatic. As she points out, with language it is possible to detach from the immediate experience. However, given that between the lived and the represented there will always be an insurmountable gap, to access the intensive dimension of the experience, other clinical strategies may be necessary.

In this sense, when we started the Clinical Testimony Project, we decided to try new clinical-political devices, considering their invention as an inseparable part of the therapeutic process. Likewise, when the opportunity to combine a clinical act with a political act of reparation was presented, the importance of testimonies, already announced in the name of the Project, soon became clear. As we heard from several participants, the possibility of testifying in the Amnesty Commission and in the Truth Commissions, putting themselves forth as agents in the construction of memory, denouncing the violations, identifying the names of torturers and places of torture and receiving the state’s apology, played an important role in therapeutic processes.

Immersed in this collective experience, we started to understand the practice of testimony as one of transmission, that, in addition to bringing to light denied events, was a call to the responsibility of the state and an invitation to new testimonies.11 In contrast to the effects of torture that aim to radiate terror and break the social fabric, these narratives are not only valid for what they say. They are also valid for the present absences they evoke, for the remnants of memory that in turn foster collective construction, and for the simultaneously public and private, political and subjective processes that they trigger, binding everyone to their share of the responsibility for the construction of this history.

In the first two years of our Project testimonial opportunities were frequent, however, coinciding with the final stages of the work of the Truth Commissions, we focused more on the construction of clinical devices for the elaboration of traumatic memories.12 Considering trauma’s capacity for fixation and the importance of breaking silence in order to work toward the deprivatization of damages, we offered different types of group strategies as modes of intervention in the private experience of violence – intergenerational groups of affected second and third generations (sons, daughters, granddaughters and grandsons of those afflicted), military who also suffered torture, couples, and families. We applied cartographic methodology – a practice that instead of a predetermined method of research and set of questions to be answered rather engages with findings as they emerge – to collectively evaluate the processes.13 In addition, to make way for the intensive components of the lived experience, we concluded that it was necessary to offer other forms of expression. Although we already used bodywork, we also realized the need for other aesthetic resources. In this sense, holding the exhibition/event Destempos: Testemunho como prática poética [Out of Time: Witnessing as Poetic Practice] was fundamental to reaffirm our ethical-aesthetic-political perspective, especially in this moment of deconstruction of reparations policies. According to the psychologist Jorge Bondía, “experience is what affects us, what happens to us and not what has an effect and what happens.”14 Using different languages and the agency of heterogeneous components of enunciation, not to represent horror, but to activate the ability to affect and be affected and integrate the intensive components of lived experience, Destempos contributed to the subjectification of the experience and the creation of another destination for these marks of suffering.

That this activity was carried out in Bairro da Saúde [Literally Health Neighborhood – an urban neighborhood in Rio formerly the main port area of the city and central to the slave trade], where silencing policies were systematically used to cover up the violations of the post-abolitionist period, did not let us forget the role of state interventions in disputes over the meaning of memory. Furthermore, that such an exhibition/event – not casually named Destempos and hosted by the performance company of Mysteries and Novelities present in the neighborhood for many years – occurred between the wrapping up of the Clinical Testimony Project and the beginning of a new stage of struggle, one still to be invented, enabled us to live the experience inhabited by the question: what memory of this new time is in store for us?

To narrate this event and deal with its unfinished dimension, we looked to Amery, Artaud, Benjamin, Deleuze, Derrida, Ferenczi, James, and Nietzsche for inspiration, informed by the powerful interpretations of Lapoujade, Lissovsky, Gagnebin, Gondar, and Rauter. David Lapoujade, quoting James, says that the task of philosophy “is not to seek the true or the rational, but to give us reasons to believe in this world.”15 To someone who loses confidence in the world and can no longer act, James proposes a philosophy that makes our action possible again. Not a philosophy that we can believe in, but rather a philosophy that makes us believe.16 This seems to have been the greatest vocation of Clinical Testimony Project. Despite its short duration, the Project made it possible to trust the world again and recover the best of our utopias.

Time 3: Opening New Landscapes: The Construction of the Destempos Exhibition

The world is good, Sebastião!

A new day will dawn tomorrow!

Tomorrow!

It will be a beautiful day

Of the craziest joy

that one can imagine

Tomorrow!

Redoubling strength

Upward that never ceases

There’s something to avenge

Tomorrow!

Nando Reis

At a certain point [in the Project], the idea of an exhibition/event began to be discussed. It was Anita Sobar, a young artist and member of the group of Children and Grandchildren for Memory, Truth, and Justice, who made the suggestion. Proposing to hold an art-testimony exhibition/event and offering herself as a curator, her idea was to enable the testimony of those affected by the violence of the state, making use of creative enunciation. Inviting experimentation with other languages, not for “the illustration or representation of horror”, but for “the activation of the legacy of this force to (re) exist”, her proposal was to use “art as a possibility to convert violence and trauma into the potential to act, think, and create.” To this end, she suggested “making private archives public for a real reinvention of writing / weaving in-between public and private, breaking barriers of silence and enhancing the struggle for truth, memory, and justice”.17

Approval was unanimous. Furthermore, the fact that we were so close to the Morro de Providência – literally “Providence Hill” widely considered one of the first Rio favela communities established in 1897 by ex-slaves and ex-combatants of the Canudos Revolt [in Brazilian state of Bahia] and the territory where one of the biggest popular uprisings in the city had taken place – soon gave rise to the idea of closing the exhibition and presentations with a procession in the vicinity. To highlight the stratagems of official memory, the market where the riot took place no longer existed. A military police barracks was built there together with a public square unofficially called Praça da Harmonia [Harmony Public Square]. The intention was to dedicate the first part of the exhibition/event to the testimonies of the participants in the Project, ending with a public performance and an account of the history of the territory, led by Felipe Lott, nephew of a formerly tortured political prisoner and grandson of an ex-deputy murdered during the dictatorship. This would allow us to bridge two moments of the past, the most recent, engaging those part of the Project, and the more remote, open to the participation of local residents.

We could not imagine the power of what would come. While some wrote a manifesto calling for the continuation of the Clinical Testimony Project, others conceived their presentation proposals, with or without the presence of therapists, but with the delicate and poetic listening of Anita who, in partnership with Dario Gularte, (filmmaker and curator responsible for filming the event), visited archives and personal records, recovering various objects and fragments of stories, hitherto invisible or silenced. In addition, since they were also children of ex-political prisoners, their own participation in the Clinical Testimony Project and in the Destempos exhibition was an important opportunity to reframe painful facts in their own histories.

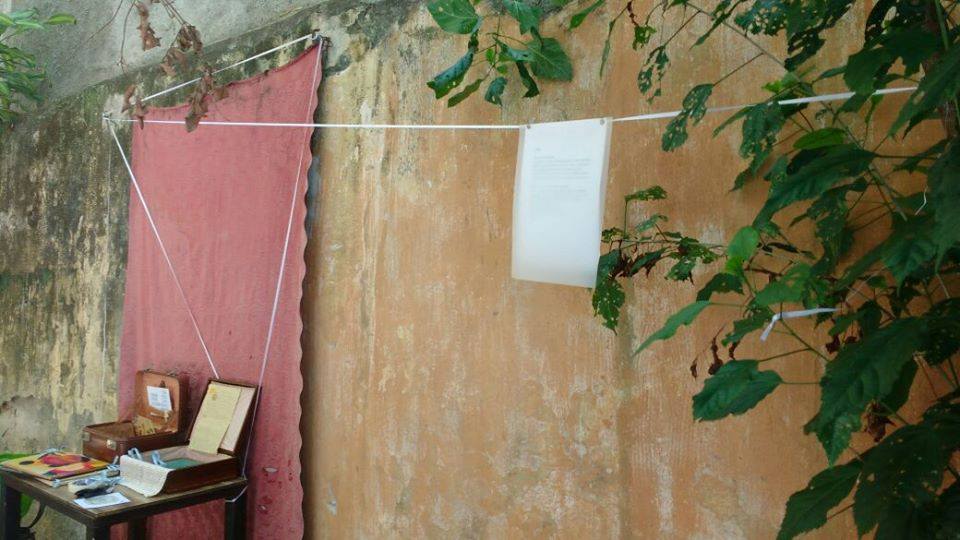

At this point, it is worth highlighting a critical shift experienced in the process. Anita, while taking care of one of the groups of the Project, remembered a moment of hearing the clink of ice in a glass of whiskey, suddenly transporting her back to memories of her father and the incomprehensible universe of the frightened child she had once been. Torn between the collective responsibility she was assuming for those in the Project [in her role as curator/filmmaker] and the image of her father’s torment, Anita experienced moments of paralysis. Could she continue to listen to what she had silenced for so long? Now, as part of a collective, she didn’t need to be alone with this decision. As the will to build memory and fight for reparation was affirmed by everyone, a new ethical choice could be made. Texts written in the heat of struggle and flight were shared; poetry, drawings, and letters from those who had been in prison were taken out of drawers; interdictions and silences that had been normalized were abandoned and the “vision” of a new time began to emerge. As Walter Benjamin notes, memory is not a deposit of defunct things, nor a one-way street, it is in the now that the past and the future are touched and transfigured.18 The proposal of the exhibition/event, in addition to looking for marks and vestiges frozen in time, was to reopen life and narratives for new connections.19 Here, the offer of diverse media and non-linguistic forms for the construction of testimonies could help to access more intimate corporal and affective memories. “What history captures from events is its effect on the state of affairs,” as Gilles Deleuze points out, “but the event in its becoming, escapes history.”20 What was important now, more than redoing the ties between words and events, was the offer of other languages that escape the limitations of pre-existent planes of forms and representations and connect us to the plane of forces, more open to becoming and the still unrealized dimension of the present.

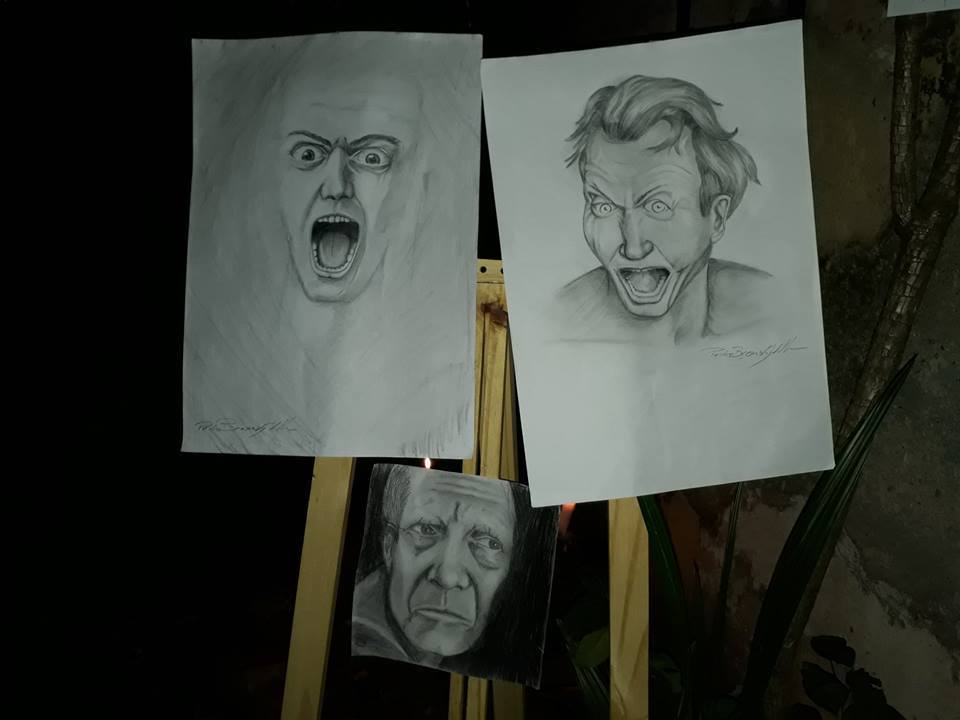

If the testimonies we had heard up until then mostly accounted for what could be narrated, [this dimension of other languages] meant that we could now also build upon the memory of various objects from the past and figuration through images. According to the psychologist Jo Gondar, as in traumatic dreams, the possibility of expressing oneself through images already implies some psychic work, given that this very work created something where only formless impressions existed. Therefore, unlike representation, figuration is a presentification. Through it the traumatic experience can be captured and some kind of connection to the intensity can be made that, until then, only existed in the raw state.21 It was what we could see with the drawings of Pedro Brezensky Villela, son of the former political prisoner, Carlos Gomes Vilela Filho. Pedro, one day, brought us his portfolio with old drawings, just to illustrate his difficulty in finishing what he started, and without paying attention to the strength of his tracings, or realize how much they screamed (or cried). On this day, despite my comments on the anguish they expressed, it was clear that he had not realized how he had managed to make it communicable. It was necessary to wait for the day of Destempos to finally cross the gap that had been erected between him and himself and between himself and the world. Until then, it was as if his scream had not been heard by anyone, not even by himself. More than that, he had not even realized what his drawings expressed. They were just drawings.

4th time – Traveling Together

Here, some time ago I reached that central point from where I discovered the truth: that my life is hopelessly poor. Not that I lack anything. I go to concerts and exhibitions, I read a lot of books and magazines, I have a reasonable library of books and records, I have friends and relationships, in short I am lacking in nothing to live a good life. But a kind of ditch was created around me. It is invisible, but it is there, and it is felt even in the middle of the most exciting concert […] There is a big hole in the middle of people that drowns out their speech and absorbs the voices that come from others. It was this hole that I discovered in myself and that I never stop seeing.

José Gil22

The loneliness of those who cannot trust themselves or the world is a feeling familiar to people affected by state violence. Unlike forced exile in foreign lands, which carries the permanent expectation of a return, former political prisoners are victims of insile in their own country, where there is no way to return, because, generally, there is not even the perception that one is/was no longer there. According to psychologist Jean Améry, those who have been subjected to torture are unable to feel at home again.23 This statement gives us the measure of the damage, since we are not talking about the loss of confidence in someone or an institution, but the loss of the ability to trust and the experience of not feeling safe even in one’s own body. In the end, the world loses all significance, nothing seems to matter; all action either appears affect-less or, on the contrary, in altering a hard-won life balance, seen as an undesirable invasion.24 The consequence of this, in the most severe cases, may be a psychic functioning aimed at trying to neutralize any possibility of being affected.

If experimentation is the condition of creation and for the realization of our exhibition/event, it was necessary to trust, how could participants surrender to the collective experience, if neither the state’s willingness to support reparations could be counted on, nor the continuity of the process? While these two conditions had ceased to exist, it was still possible to count on the creation of dimensions of common experience, where everyone would be in the same boat, adventuring together. It was at that moment that we started preparing the exhibition and, totally outside our comfort zones (including for the therapists) that we literally needed to trust “confiar” one another (and “fiar com” work together). [T.N The phrase plays on the Portuguese words that share similar Latin roots and sounds “confiar” meaning trust and “fiar com” meaning to spin / tie with].

Testimonials

When we heard Sebastião being called by Mariana, in one of the opening moments of the event, we were transported to that place “out of time”, where he was able to narrate, for the first time, his story. We were then introduced to that 23-year-old boy who studied psychology, did theater, wrote poetry and was involved in the student movement. It had been pre-arranged that, in order to help him recall the scene, Mariana would call his name, just as the agent of repression had done, at the time of his arrest. Without dwelling on the account of his kidnapping and torture and showing the only page left of the poetry book manuscript he had just written when his arrest took place, Sebastião intended to talk about the day he recovered it, three months later. As the manuscript had been returned to him with the notes of an agent of repression, criticizing his ideology, but praising his writing style, Sebastião had never wanted to open himself up to creating again. To do so would, in some way, please the torturer, which would be totally intolerable. However, as Mariana was not able (or did not want to) reproduce the threatening tone of Sebastião’s kidnapper and, on the contrary, she called him as she would have called him if that encounter, in 1972, had been with her, something gave, deviating the direction of his story and bringing back, not the Sebastião from the moment after the arrest and torture, but the one who wrote poetry and loved the theater. Just like the tinkling of ice in the whiskey glass, which for a moment had connected Anita with her father’s suffering, to immediately thereafter connect her to the power of her current collective, the contact with Mariana’s call dislocated him from the place that had remained in silence, allowing him to finish his testimony with a subjective position different from the one he started. Since resisting the torturer had required him to no longer express himself creatively publicly, now the motivation to silence had lost its meaning.

If I refer to Sebastião’s account as a testimony, it is also to understand it as a performative act, necessarily relational. In addition to communicating what happened such a testimony triggers new processes of subjectification both in those who speak and in those who listen. This means that the role of testimony is not to produce objective evidence for an investigation, although their information is essential to bring to light what had previously remained hidden. As psychologists Alexei Indursky and Karine Szuchman point out, the requirement to “tell the truth, nothing but the truth” imprisons the witness to the past and the fear of contradiction, preventing them from giving an account of the effect of the traumatic event on their life.25 On the contrary, while the legal paradigm requires the witness to report ipsis litteris how the facts took place, the process of becoming-witness – in addition to ending the mandate of silence and making sayable the limit experience of tortured and torturer – is capable of reopening the watertight versions of history and activating the ability to create new meanings.

If “nothing that happened can be considered lost to history” and “each event harbors a seed of eternity that is like a ‘reserve to come’ […] if “the event is left behind, but what remains of it in me in the present is not its consummate past (its ‘perfect past’), but that which comes from the past and leaps into the future (the ‘past future’),” it is in memory and in a new connection between past and future that one can find the writer that Sebastião would have been.26 And it is at that moment that the event can be recognized and find its transfigurative power. For Benjamin, this would be the task of the historian-scavenger, capable of identifying in the past the germs of another history and sifting out what events, in the apparent continuity of time, have the power of detachment and re-enchantment.

In turn, Mariana, who had begun to draw and write poetry during her imprisonment, was able to read her work for the first time in public and share her sad but beautiful poetic images. Treated until then, as “hysterical crises”, without any historical or aesthetic value and kept under lock and key after her release, these images required the (re) encounter with Sebastião and the sensitive listening of the other participants in Destempos to be recognized as the strategy that kept her alive and in a state of creation, in a place that specialized in assaulting dignity and obtaining information. At that moment of great solitude, she was also given access to a rich imaginary, full of popular stories, which allowed her to feel in the company of beloved people and to invent, like Sherazade, a series of narratives and to escape the tactics used by the torturer to keep her under his yoke and power. For her, so attuned to the art of storytelling, life was able to continue its flow, although, due to the forced flight and exile and the death of so many companions, she had never been able to recover her original community. In that sense, her experience at Clinical Testimony Project and her possibility to share her stories again worked as if she was back in her homeland.

At this point it is worth returning to the dialogue with Benjamin, who between 1933 and 1936 wrote his articles on the end of the experience and its possibility of transmission. In these texts, Benjamin reflects on the narrative incapacity of the soldiers who returned from the front and on the state of shock experienced by a generation “that still went to school in a horse-drawn tram” and was now going through not only a bloody war, but also radical subjective transformations triggered by the development of capitalism and the breakdown of community forms of life.27 According to Jeanne Marie Gagnebin, one of the conditions for the preservation of the art of narration is that the experience transmitted by the story is common to both the narrator and the listener and that both are inserted in a common narrative flow, open to doing it together.28 When common memory and tradition no longer exist and when the possibilities of collective experience cease, the saving force of memory cannot be counted on. There remains the individual isolated in the face of shock and meaninglessness.

The opposite, however, can also occur, when the conditions for a collective experience are given. It happened when we heard the dramatized reading that Henrique Lott made of his uncle Noilton’s account of the experience of torture.29 Accompanying him until the end was tremendously distressing, but having that sensorial experience, that it was so literal, was essential to produce a collective memory. As mentioned above, it is often said that it is not possible to narrate torture. Or for those who suggest such narration as a possibility they note that this is only possible through a literal description, an accounting of the “bone of things”. For Gondar, this is what can be seen in the poetry of Paul Celan, or in the theater of Antonin Artaud. According to her, Artaud understood that “in order to reach the bone, it is necessary to risk losing the meat. Literalness would be exactly that language without meat, a dissected language that moves in a straight line, without any sinuosity or masking, to the hard bone of the real.”30

This experience also revealed that, in order to deal with the accounts of torture, it is necessary to be willing to feel with and not to talk about. As torture rules the mind and body, surrendering its functions to the most unknown and uncontrolled reactions, tortured people often resort to dissociations, as a way to keep these memories at bay and make it possible to continue living. Upon hearing the account of Henrique’s uncle – who at times adopted the perspective of the torturers (as if to try to understand the mechanics of torture and to understand what they wanted to produce in him) and at others he referred to his mental functioning, as if it was someone else (as if the description of his deconstruction was a form of reappropriation of himself) –, we were constituting ourselves in/as a collective body, transformed by what we heard, as the only way of getting through that dilacerating testimony, without getting torn apart.

At one point, however, Ana got up and was about to leave the room. Getting close to her to comfort her, we learned that, during a session of torture, the military had confronted her with statements of Henrique’s uncle. When we asked how she felt, her first response was a hesitation, a pause for self-observation. Then, realizing, for the first time, that she could hear such an account, without having to run away from herself, she ended up returning to the others. This helped us to understand that those who cannot listen to tortured people, leaving them alone with the experience of horror, may have gone through a similar situation. Thus, what might appear to be negligence, or indifference, would be precisely one of the effects of torture, with the objective of isolating, separating, cutting the links of the tortured with their own affections and those of others. For Ana, who had been savagely tortured, listening to that story and thinking about the strategies of the torturers, gaining some exteriority in relation to them and building a collective meaning for the experience, was a fundamental event, which only became possible, almost 50 years later.

At that moment, the ambient anguish and the place where we were, invoked the theater as an intensive experiment proposed by Artaud. Breaking with the representational model and based on the bodily experience of the actors and the audience, Artaud imploded the idea of spectacle and proposed a type of staging in which the scenes and language itself had to be invented pari passu with experience. Referring to Western theater as the one in which the author-creator, “absent and distant, armed with a text, watches, gathers and commands the time or sense of representation” and in which the audience is nothing more than “a passive audience, seated, an audience of spectators, consumers,” Artaud proposed to end the tyranny of the text and its representational language, restoring to the stage its instinctive freedom, using unconventional spaces and investing the creative function to all participants, including to those traditionally seen as the public.31

Although most of us were stuck to the old theater chairs used to compose the environment, at that moment it was as if we were all Noilton – the fictitious name we gave to Henrique’s uncle since he was not a participant in the Project – and we could count on the collective body to deal with that experience of demolition. Furthermore, the fact that this account was being read by his nineteen-year-old nephew was not a minor detail. Unaware, until then, what his uncle had lived through, the young actor could now transmit this experience no longer via relating symptoms, but through art.

Installations, prison letters, photos, paintings, drawings and performance:

With Benjamin, we found ways to escape the logic of representation and discover the strength of fragmentary aesthetics, essential to witnessing activities relating torture. In this regard, in order to endure the anguish that took over the environment, it was important to have the opening speeches of Anita and Dario, the drawings of Pedro, the paintings of Tossiro Komoda32 and the installations of Mariana Lydia and Fiora. Building and connecting affections through images, as much as linking texts and affections, produced a new body capable of coping with those intensities. We were moved by three generations of the Campos family, making art where there had been so much pain.33 We cried accompanying the poetry of Maria Leão written for her grandfather Rubin Aquino, already deceased. We could laugh and sing with Luciana Saldanha’s poetry,34 as well as take a trip into the past with Beatriz Vieira’s washing line of poetry, the recreation of her space of mementos in the exhibition and the reading of her father’s letter, the former political prisoner Lizt Vieira, now torn by time. As Dario suggested to us at the opening of the exhibition, our proposal was to: “Experiment. Explore the continuous and discontinuous layers of time, of memories; the density of memory, objects, existence” and “our challenge was to compose (ourselves), produce (ourselves) and show (ourselves).”35

Likewise, the presentation of clips from the film Soldados do Araguaia,36 followed by a testimony from a former military man who had suffered torture for not collaborating with the regime,37 and the exhibition of Leo Alves Vieira’s video-performance, contributed to offer us an aesthetic support for Destempos’ floating affects. Grandson of the disappeared politician Mário Alves and one of the founders of the collective Sons, Daughters, Grandsons and Grandaughters for Memory, Truth and Justice, the musician and composer Leo presented his work Trabalhadores [Workers], which, like his other compositions, is characterized by a fragmentary aesthetic. In one piece, called Tortura Nunca Mais [Torture Never Again], Leo even uses repulsive fragments of the sound of the voice of one of his grandfather’s torturers, on the occasion of his testimony to an audience of the Rio de Janeiro state Truth Commission.

An equal integrating force could be experienced with the curative dance of Ana Bursztyn-Miranda and Marília Felippe, as well as with the paintings of Fábio Campos and the graphic minutes of commission hearings by Luis Zorraquino.39 The latter, accompanying the presentations, witnessed the movement of art production and the recreation of life in real time. In the case of Ana, who started her presentation inside a chalk circle, we were able to accompany her in the movement out of the subjective prison, her first tentative steps, her dance with Marília and the finalization of the performance, with the reading of her “license to be free” – her official prison release – together with an interpretation of the poem “Mãos Dadas” [Hand in Hand] by Drummond de Andrade.

I will not be a poet from a fallen world,

Nor will I sing the future world.

I am stuck with life and I look at my companions

Among them there is an enormous reality

The present is so big, let’s not go too far away

Let’s not go away, let’s go hand in hand.

Time is my subject, present time,

present men and women, the present life.

Watching her release from prison, her opening up not only to dance, but also, to dance (in the infinitive) as a creative possibility, touched everyone who participated in the exhibition, providing the support we needed, after sharing such painful experiences. In this universe open to new connections, it was finally possible to detach from the lived past and risk experimenting new steps.

The night progressed. The activities having extended much longer than anticipated made the planned parade unfeasible. Whatever was going to be left out of the event, had not even entered the agenda of reparatory policies, initiatives that had only taken their first steps with the creation of CERPs. If our shared experiences had helped us to get out of the chalk prison and all of us be Sebastião, Mariana, Noilton, and Ana, the Project had achieved another kind of exercise of memory, other than a literal one. According to historian Tzetvan Todorov, there are two possible uses of memory: the literal, which implies a personalistic cult in relation to the past and in which memory becomes an end in itself; and the example that, when making an active use of memory, the past is used with the aim of fighting against the continuation of injustices.40 Thus, if the use we make of memory is one that can allow us to deploy it as a political practice of resistance, its power lies in the way in which we articulate ourselves with the struggles of the present and contribute to a different future. If some memories find more spaces for listening and certain lives may have more protection than others, it is necessary to counter such inequity. In this sense, it only makes sense to continue the fight for the resumption / expansion of the reparatory agenda, to join the movements to end the genocide of black people and build strategies for the articulation and transversalization of our common agendas.

***

Tania Kolker

Is a psychoanalyst. She holds a degree in medicine from Universidade Federal de Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and a specialization in psychoanalysis and institutional analysis from the Brazilian Institute of Psychoanalysis, Groups and Institutions. Currently she is a master’s student in the graduate program in psychology at Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF). She is coordinator of the Psychosocial Care Center for People Affected by State Violence (NAPAVE) and researcher at the National Observatory on Mental Health, Justice and Human Rights. Formerly she was coordinator and therapist of the Clinicas do Testemunho Project (2016- 2017), supervisor of the ISER-RJ Psychic Repair Study Center, therapist of the clinical project of Grupo Tortura Nunca Mais / RJ (until 2010), and consultant for the Association for the Prevention of Torture in Brazil (2007-2013).

1 The Centros de Estudo em Reparação Psiquica (CERPs) [Psychological Reparation Study Centers] were initiated in the states of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande de Sul between 2015 and 2017 but were discontinued by the Temer administration (2016-2018) following the impeachment of Presidente Dilma Rouseff in 2016.

2 Eduardo Losicer, “Potência do testemunho: Reflexões clínico-políticas” in: Cardoso, C et al eds., Uma perspectiva clínico-política na reparação simbólica: Clínica do Testemunho do Rio de Janeiro (Brasília: Ministério da Justiça, Comissão de Anistia; Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Projetos Terapêuticos, 2015) p.31 [Available online: https://www.justica.gov.br/central-de-conteudo_legado1/anistia/anexos/clinica-do-testemunho-rj-on-line.pdf]

3 Núcleos do Projeto Clínicas do Testemunho [Clinical Testimony Project Groups] were created in four Brazilian states. In Rio de Janeiro the group comprised the following therapists: Cristiane Cardoso, Eduardo Losicer, Gabriela Serfaty, Janne Calhau Mourão, Marília Felippe, Olívia Françozo, Tania Kolker and Vera Vital Brasil.

4 Francisco Ortega, “Rehabitar la cotidianidad” in: Veena Das, sujetos del dolor, agentes de dignidad. Ed. Francisco A. Ortega. – Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Facultad de Ciencias Humanas: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Instituto Pensar, 2008.

5 Silvia Helene Tedesco, “Linguagem: representação ou criação?” in: Virginia Kastrup et al, eds. Políticas da Cognição (Porto Alegre: Editora Sulina, 2008).

6 Cecília Maria Bouças Coimbra. “Reparação do crime de tortura.” Presentation at the launch of “Guia para la denuncia de torturas”, México, March, 2001.

7 In the Portuguese version the author uses “outramentos” drawn from “to other” [outrar-se] a neologism deployed by the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa.

8 As Rauter tells us, even though violence is individualized “the real target of torture is the group [itself, seen] as an experience that is intolerable to power. Nothing is as unbearable to the capitalist state as the group, the collectives that can be organized against it.” Thus, even when the violation does not seem to have political objectives, it is the collective that is aimed at. The very distinction between lives that must be protected by the state and lives that are considered a threat is a strategy of divide and conquer. In: Elizabeth Araújo Lima, Luis Eduardo Aragon, João Leite Ferreira Neto eds. Subjetividade Contemporânea: Desafios Teóricos e Metodológicos. 1ed. Curitiba: CRV, 2010, v. 1, p?

9 In Jo Gondar, “Ferenczi como pensador político” in: Cad. Psicanál CPRJ, Rio de Janeiro, v. 34, n. 27, p. 193-210, jul./dez. 2012, p. 196.

10 See Cristina Rauter. Clínica do Esquecimento (Niterói: Editora da UFF, 2012)

11 Jean Philippe Pierron. Transmissão – uma filosofia do testemunho (São Paulo: Loyola, 2010).

12 Cristiane Cardoso, Marília Felippe and Vera Vital Brasil eds. Uma perspectiva clínico-política na reparação simbólica: Clínica do Testemunho do Rio de Janeiro. (Brasília: Ministério da Justiça, Comissão de Anistia; Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Projetos Terapêuticos, 2015).

13 The objective of cartographic methodology is to accompany and potentialize processes, identifying points of closure and potential opening and change. See Eduardo Passos et al eds. Pistas do método da cartografia: pesquisa-intervenção e produção de subjetividade (Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2009).

14 Jorge Larrosa Bondía,”Notas sobre a experiência e o saber de experiência” Rev. Bras. Educ. [online]. 2002, n.19.

15 David Lapoujade, William James, a construção da experiência (São Paulo: n-1 edições. 2017) p. 16.

16 Idem.

17 Excerpt from Anita Sobar’s invitation to the exhibition/event invitation.

18 “One Way Street” is the title of a text by Walter Benjamin.

19 Diverging from traditional visions of history that represent a linear or dialectic narrative, Benjamin proposes to brush against the grain of history, indissociable from the fragmentary memory of the oppressed invoking the figure of the historian as a scavenger of remnants and silent remains rather than that of working their way through organized archives.

20 Gilles Deleuze, Conversações (Rio de Janeiro: Editora 34, 1992), pp. 210-211.

21 Eliana Schueler Reis and Jo Gondar, Com Ferenczi: Clínica, subjetivação e política (Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras, 2017) p. 74.

22 José Gil. “Quase feliz” in elipse, gazeta improvável, nº 01, spring 98, pg. 6.

23 Jean Améry. Além do crime e castigo: tentativas de superação (Rio de Janeiro, Contraponto, 2013).

24 Idem, LAPOUJADE, 2017.

25 Alexei Conte Indursky and Karine Szuchman “Grupos do Testemunho: função e ética do processo testemunhal” in: Clínicas do Testemunho – reparação psíquica e construção de memórias (Porto Alegre: Criação Humana, 2011).

26 Maurício Lissovsky, “A memória e as condições poéticas do acontecimento” in: Jo Gondar and V Dobedei eds. O que é memória social (Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa Livraria/ Programa de Pós-graduação em Memória Social da Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, 2005) p. 137.

27 Walter Benjamin, Magia e técnica: ensaios sobre literatura e história da cultura (São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1994, 7ª edição) p. 198 .

28 Jeanne Marie Gagnebin, Lembrar escrever esquecer (São Paulo: editora 34, 2009).

29 We used Noilton as a fictious name to refer to Henrique’s uncle, as he did not participate in the Clincal Testimony Project.

30 Eliana Schueler Reis and Jo Gondar, Com Ferenczi: Clínica, subjetivação e política (Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras, 2017) p. 46.

31 Jacques Derrida, A escritura e a diferença. (São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2011).

32 Tossiro, a university student arrested when he was 23 years old had not managed to recover from his experience of torture, becoming physically ill. Painting was his only salve from his pain.

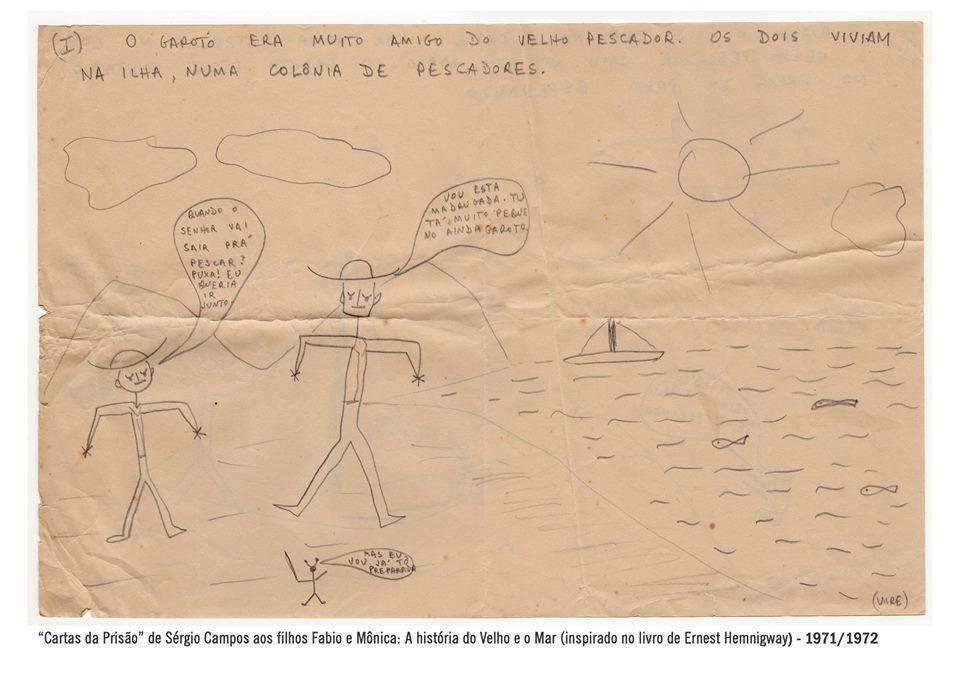

33 Sérgio Campos, a former political prisoner, his sons Fábio and Vinícius and his grandchildren Pilar and João presented a collective work, composed of photos, drawings and poetry. Some letters from Sérgio were also exposed, written in prison for his children and Fábio played some of his songs and painted a picture during the event.

34 Luciana, granddaughter of Aristides Saldanha, constitutional representative of PCB in 46 and grand niece of the journalist João Saldanha, read her poetry “Menina Vermelha” [Little Red Girl].

35 Excerpt from the text read by Dario Gularte at the opening of Destempos.

36 The film Soldados do Araguaia [Soliders of Araguaia] by Belisário Franca and Ismael Machado, tells the story of soldiers from poor communities that participated in the repression of the Guerrilhas of Araguaia, made up of Brazilian Communist Party members.

37 I do not list her all the names of those who participated, just those who gave their authorization to be named in this essay.

38 For more information see Leo Alves and Juan Antonio Nieto, Data, 2021 https://musicainsolita.bandcamp.com/album/data

39 Luis Zorraquino, architect and artist, in addition to the graphic minutes drawn throughout the event, also exhibited a painting made in honor of his deceased partner, the former political prisoner Estrella Bohadana.

40 Tzvetan Todorov, Los usos y abusos de la memoria (Barcelona: Paidós, 2000).