Navigating in a Haunted Landscape: A Tale as a Tool at Morro do Bumba

Sandrine Teixido

In 2010, while archiving articles on the “Bumba Tragedy” – the disastrous garbage and mud landslide that killed more than 250 people and left many more homeless in the Morro do Bumba [Bumba favela] Niterói, outside of Rio de Janeiro – I never imagined how central this event would become in my artistic future. “Bumba” would become part of and further my commitment to A tale as a tool – a project in development since 2011 together with the Swiss artist Aurélien Gamboni. In its tragedy and regeneration, Bumba would come to represent from the beginnings of our project in 2010 to the more advanced collaborations in the collective exhibition Baia de Guanabara: Águas e vidas escondidas [Guanabara Bay: Hidden Lives and Waters] at Museum of Contemporary Art Niterói (MAC) in 2016, a fertile terrain for a form of art making that combines collaborative research and practices at a time when the anthropocene forces you to learn to live in the “ruins of capitalism”, in the words of the American anthropologist Anna Tsing.1

In contexts such as Bumba, A tale as a tool proposes the use of America writer Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “A Descent into the Maelström” (1841) as a tool in three different ways.2 Firstly, the narrative structure allows us to establish a certain type of investigation that emphasizes attention to the environment. Secondly, the model proposed by the story opens up the possibility of exploring the ecopsychological potential of the figures caught in the maelstrom as an emotional journey in times of ecological crisis. Finally, the way we choose to activate these different potentials generates art forms that explore the possibilities of a “common art”.

From Bumba to Maelström and From Maelström to Bumba

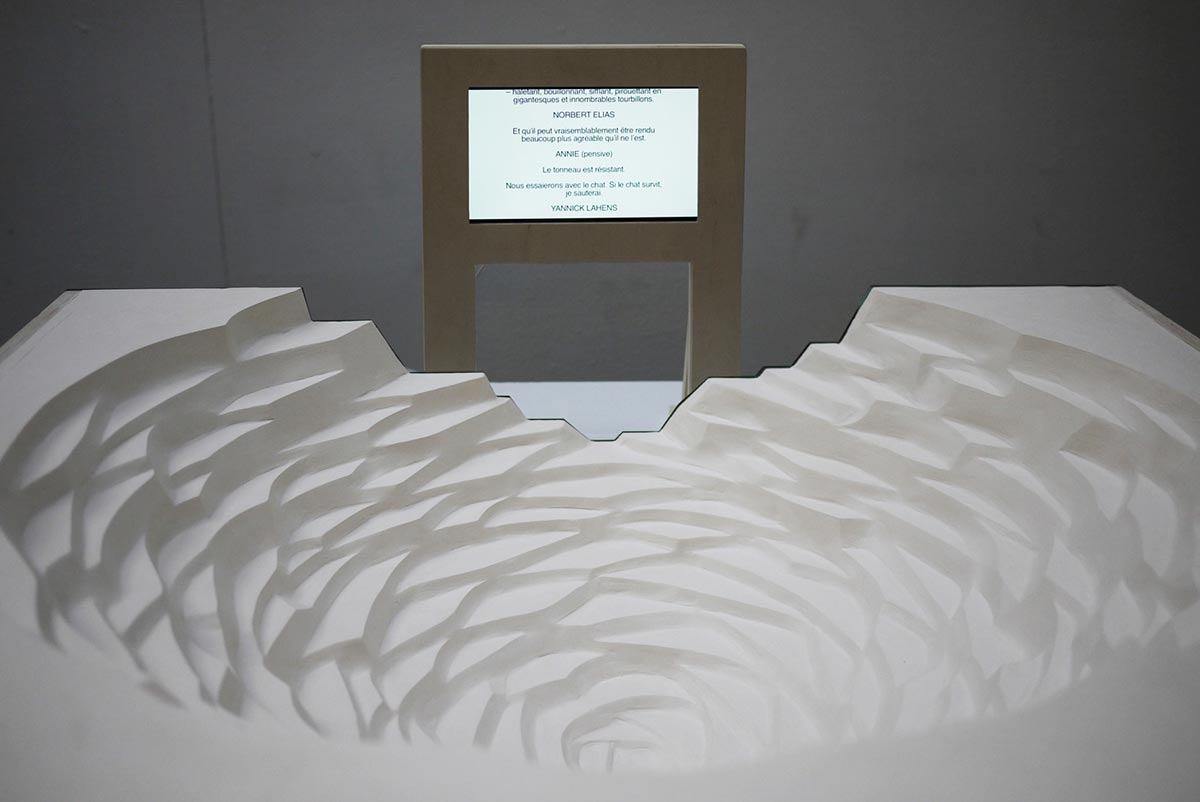

On April 7, 2010, Bumba was the epicenter of a tragedy that killed at least 46 with a further 150 missing presumed dead and countless others left homeless.3 At the time, I was visiting Rio de Janeiro and the complex and tragic circumstances compelled me to collect and archive articles from the local and national press on the subject. A year later, I started working with Aurélien Gamboni on a project called Into the Maelström to be based on Poe’s famous story. We had met during a training course initiated by the French philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour that brought together researchers and artists. We first collaborated on a reconstruction of the 2009 climate negotiations in Copenhagen – an event that had led to a non-agreement between the parties involved. In autumn 2011, we were asked to create an installation for the Les Urbaines festival in Lausanne. For this installation, Aurélien built a sculpture that represented a cyclone in the form of a hemicycle. This representation allowed us to reflect on the place of different nations in climate negotiations, imagining that the most vulnerable were closer to the bottom of the cyclone while the more favored were at its edge.

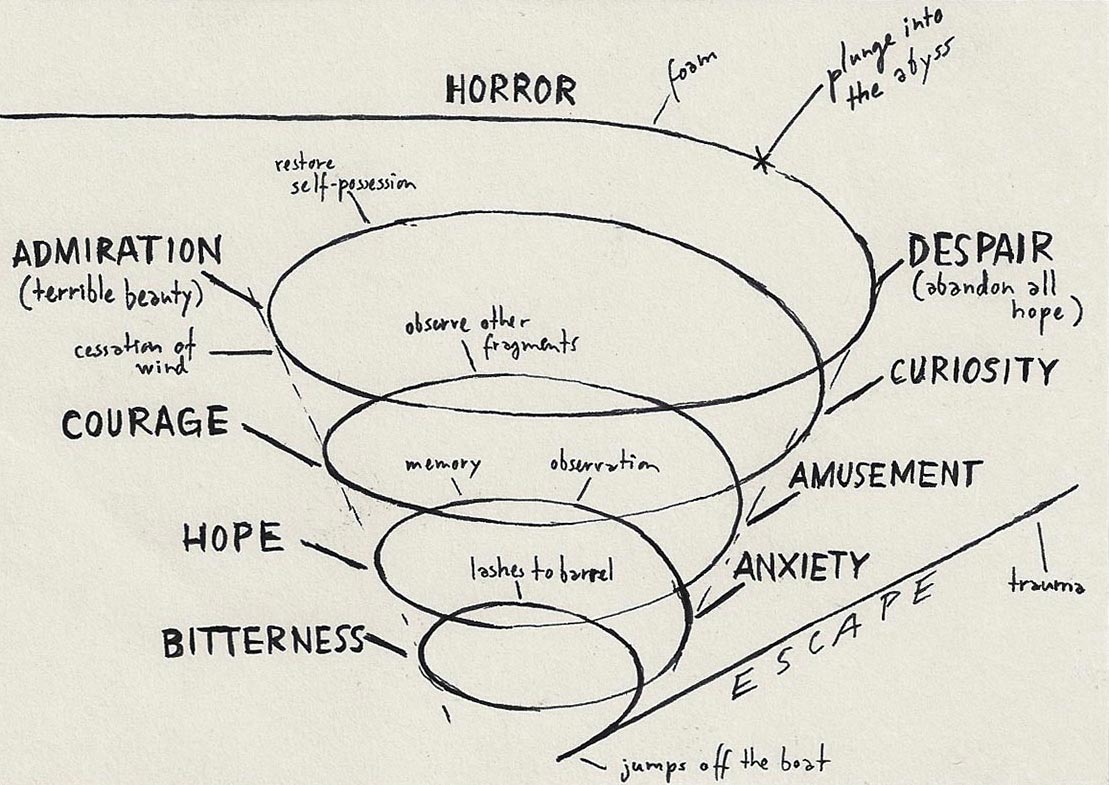

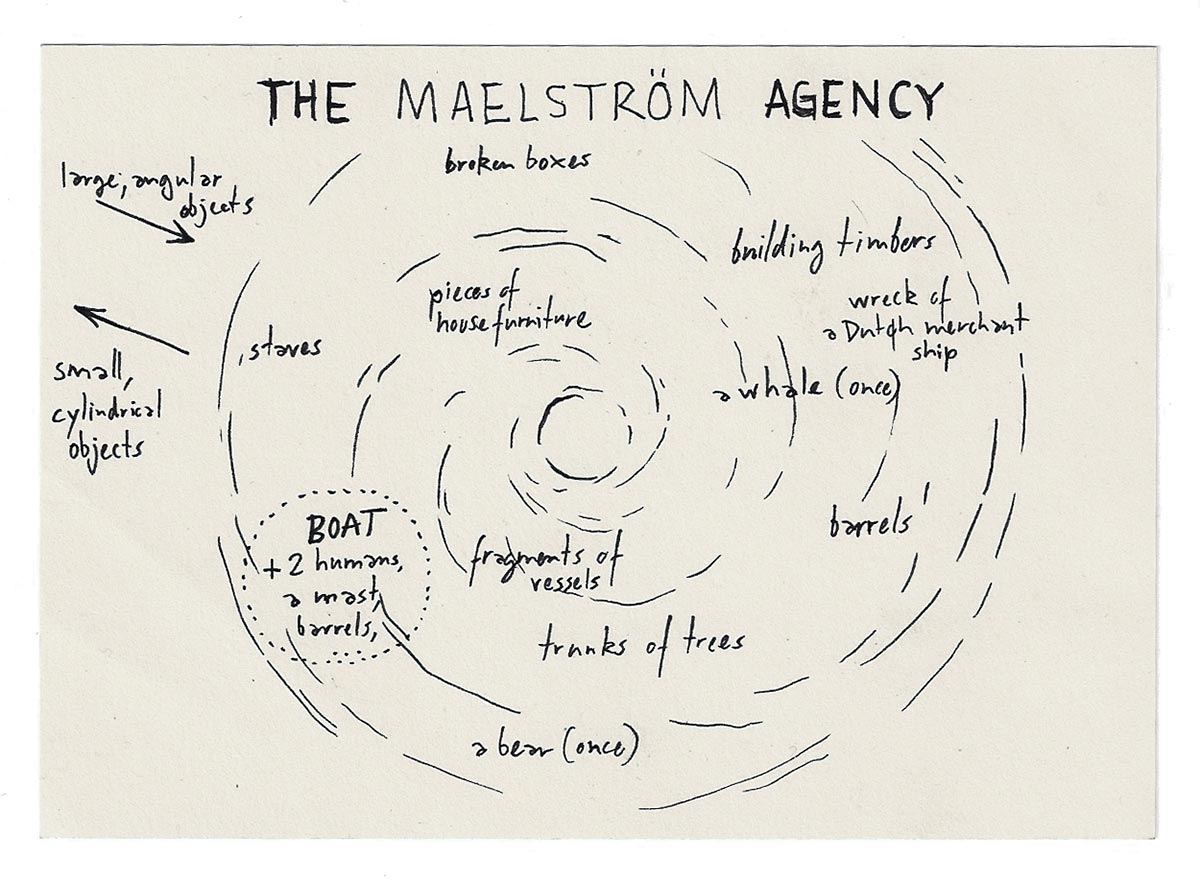

To understand this interpretation, it is necessary to return to the plot of Poe’s story. Off the coast of the Lofoten archipelago in Norway, the story presents three sailors (who are also three brothers) used to fishing in the vicinity of the maelstrom because the currents there guarantee good fishing. With their knowledge of tide times, their expeditions go smoothly until the day they are stuck in the maelstrom. Very quickly, the youngest of the brothers goes overboard while the oldest gradually sinks into madness. The second brother, who is also the survivor and the one who tells the story to the narrator, goes through different emotional phases (terror, admiration, bitterness, curiosity, etc.) before reaching a series of observations that will allow him to save himself. Key here is that in observing his environment he becomes aware that cylindrical objects sink to the bottom less quickly than others. He decides to attach himself to a barrel. So when the water engulfs him, he and the barrel nevertheless float upwards and drift together to be eventually fished out of the water by colleagues to whom he tells his misfortune, but who find it hard to believe.

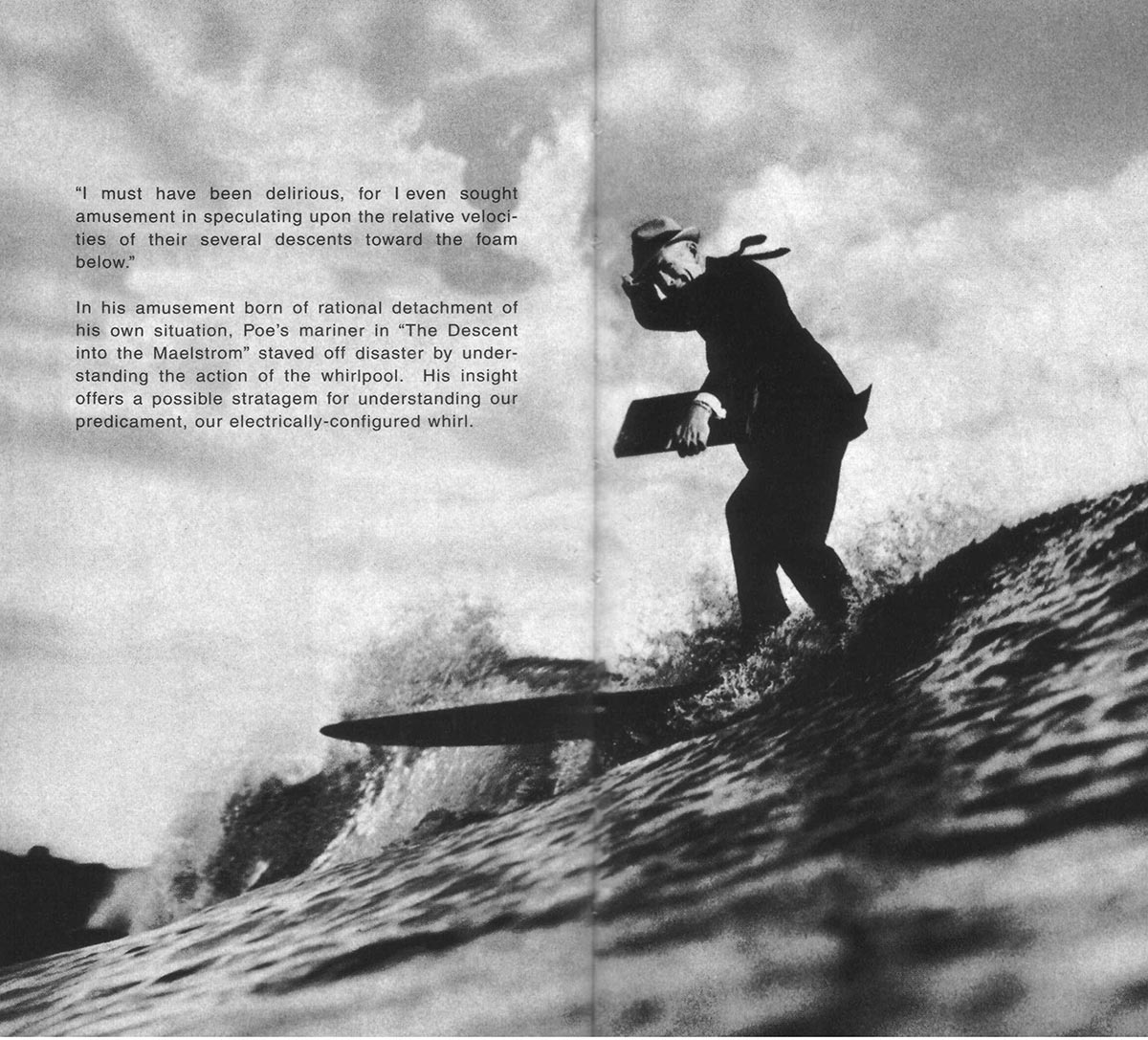

The story has drawn numerous interpretations and contemporary parallels, highlighting the diversity of ways to engage with the problems that Poe’s tale presents. Canadian theorist Marshall McLuhan sees the maelstrom as an image of the “whirlwind of electronic information” that one must learn to navigate.4 German sociologist Norbert Elias uses the tale to analyze the dynamics of a possible drift towards atomic war during the Cold War.5 Bruno Latour questions the issues of perception and adaptation linked to the “new climate regime”6, while literature professor Yves Citton addresses the “attention” challenges raised by the collapse of the “living”.7

As part of the Les Urbaines festival in 2011, we created an installation comprising a montage of climatic scenes with a screen onto which we projected a script drawn from Poe’s story, but also from events that resonated with the tale. Among these, the Bumba tragedy stood out in my memory. For the projected script I drew on comments by Bumba residents made on social media combining them as a chorus refrain in a manner similar to the famous song “Construção” [Construction] (1971) by Brazilian musician Chico Buarque. [T.N. The song describes the last day of a construction worker whose fall to his death is treated amidst a capitalist technocratic society of order and progress as merely “getting in the way of traffic / public / Saturday.”] The lyrics have the peculiarity of changing with each chorus refrain [T.N. the worker first gets in the way of traffic, then the public, then Saturday for example] resulting in different meanings and allowing Buarque to denounce the military dictatorship of the time (1964-1985). Buarque’s genius is to have imagined these changes using the sentence structure via playing with their progressive rearrangement. I applied the same process to the script for our installation, introducing the Bumba tragedy in the form of a chorus whose words gradually changed to show various ways of characterizing and critiquing this event: problems of climate change, municipal neglect, legal uncertainty, etc.

The Bumba tragedy is very much linked to the birth of the A tale as a tool project and represents our “first” field of investigation. However, unfortunately, we were not able to advance our research on Bumba in the initial versions of the project. Despite our desire to develop a specific investigation in Morro do Bumba, initial support for the project took us away from Niterói, as we were invited take part in the 9th Mercosul Biennial of Contemporary Art in 2013 held in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande de Sul in the most southern province of Brazil. Following this we went to Norway, the Lofoten archipelago, and the Arctic. Our investigations gave rise to two performed conferences held at the Théâtre de l’Usine in Geneva in 2014 and 2015. So it was only in 2015, when I moved to Rio de Janeiro, that I was able to resume a dedicated investigation into the Bumba tragedy.

I was shyly sitting in a chair in the office of the then director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Niterói, Luiz Guilherme Vergara, who seemed to be pulling his hair out to solve the many problems he was facing with the exhibition Águas e vidas escondidas, planned to take place in 2016, in which we were going to participate.8 Beside me were Ignes Albuquerque and Priscilla Grimberg. To kill time we began to talk to one another. I was surprised when I realized that they had started an entire network of affective collaboration and an open-air museum (Rancho Verde, see below) in Morro do Bumba. This chance meeting was both a coincidence and a sign that the time had come to resume the threads of the investigation that had been the basis of the A tale as a tool project.

A tale as a tool highlights the ability of Poe’s tale to provide a series of tools for understanding events where climatic, political, social, and symbolic aspects intertwine. The investigative project modeled on the story of the sailor and survivor of Edgar Allan Poe’s tale can help us find our way in situations of environmental, political or social risk – characteristics of the new geological condition of the anthropocene – where such situations are distinguished by the intertwining of political, social or environmental issues but also geological or historical elements. The Bumba tragedy is a good example of an event in which several scales, entities, and parameters – belonging to different regimes characterized by uncertainty or misunderstanding – are intertwined. The collection of information and testimonies about the tragedy tends to deepen the uncertainty as to its causes, but this process has also pointed out the invisibility of the event and the difficulty in characterizing the elements involved.

To transform Poe’s short story into a “tool” for an investigation, we draw on different possible interpretations of the news reports of tragic events such as Bumba, as well as more recent updates proposed by researchers. We then try to examine other possible uses of the story, mainly through interaction with informants on the ground. Before entering the field, we choose an appropriate translation of the story. In an interview situation, we organize a small ritual that consists of placing a map of our research on the table and summarizing the story. The purpose of these different operations is to encourage our interlocutors to pay particular attention to the issues at stake in the story. This approach, carried out with and from a fictitious narrative, enables us to experiment in very different contexts (Brazil, Norway, United States), where the actors involved have to understand the issues that Poe’s tale presents, in relation to their own situation, knowledge, and practices. In the case of Bumba, the transposition of the attention that the sailor pays to his environment allowed us to explore with the inhabitants how they managed to find their way or not in the midst of the tragedy and, subsequently, to evaluate the different analyzes that explain the event.

From Uncertainty to Ghosts: Bumba, a Haunted Landscape

There is much to say about the Bumba tragedy. But first I would like to point out how the survivors showed varying amounts of attention to the environment. Before and during the event, inhabitants were faced with audible, visual or olfactory alerts that allowed them to navigate (or not) in the chaos in which they were immersed. Subsequently, different ways of seeing highlighted the intertwined nature of the causes and entities that played a role in triggering the event: geological and climatic criteria, waste disposal, and history of the neighborhood. These elements, like ghosts, have haunted and continue to haunt Morro do Bumba. I borrow here the notion of “haunted landscape” from the work of Anna Tsing and Nils Bubandt. In their collective work, they focus on the “anthropocene ghosts and monsters”.9

The contributions to Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet demonstrate — we must share space with the ghostly contours of a stone, the radioactivity of a fingerprint, the eggs of a horseshoe crab, a wild bat pollinator, an absent wildflower in a meadow, a lichen on a tombstone, a tomato growing in an abandoned car tire. It is these shared spaces, or what we call haunted landscapes, that relentlessly trouble the narratives of Progress, and urge us to radically imagine worlds that are possible because they are already here.

Morro do Bumba can be understood as a landscape haunted by its past and more or less visible entities that the tragedy has revealed. According to anthropologist João Francisco Loguercio, the history of Morro do Bumba is absent from official documents.10 It is only through the intersection of geological, climatic, physical, and historical information that crisscrosses Morro do Bumba at a given moment that we can get an idea of the singularities of the place. Morro do Bumba is not, therefore, a landscape that exists passively, but the result of a construction between expert outsiders and local endogenous ways of seeing.11

The difficulty in demonstrating the site’s vulnerability had a significant impact on urban policy in the region. Located in the district of Viçoso Jardim in Niterói, the place where the Morro do Bumba community was established had been for a long time a devalued territory as it was situated at the end of a bifurcation to the entrance of a high risk low-income community. The peripheral location of this district and its devaluation led to its invisibility with respect to technical services (geological, topographic, climatic). According to Loguercio, the geological information provided by the Municipality of Niterói differs from surveys by the Geological Survey of Brazil.12 The characteristics of the region in terms of erosion, mass movements, carrying capacity, appropriation and land use, only appear after cross-checking information from different studies that reveal the fragility or vulnerability to which the neighborhood is exposed.

From a political point of view, the Morro do Bumba (re) emerges intermittently, following the pace of electoral deadlines and urban and administrative needs. From the 1970s onwards, the city of Niterói was faced with the need to find an extensive area where it could accommodate leftover debris and garbage produced by the population and Bumba’s bifurcation was turned into a garbage deposit until 1986. As summarized by Vilma Pereira:

Sixteen years of compacted garbage in this place still with very few houses. However, the surrounding community reacted, and as a result Niterói had to take their garbage to the Gramacho landfill in Duque de Caxias. With the deactivation of the landfill, an abandoned area was left, covered by vegetation with the need for housing by those who worked and lived there; so the first occupations, eventually called the Morro do Bumba community, started to appear. Upon hearing of the occupation, the municipal government at the time under Waldenir de Bragança prohibited the occupation of the site. But little by little, in the absence of inspection and Public Housing Policies, the first clandestine occupations began to emerge, via small brick houses. So without repressing the irregular occupation, the local government ended up encouraging the invasion.13

Niterói municipal government commissioned an analysis in 2004, conducted by a team of geologists from the Federal Fluminense University (UFF), resulting in a report coordinated by geologist Adalberto da Silva, that drew attention to Morro do Bumba, but the authorities did not seem to have taken this into account. Liguercio shows how the creation of the garbage dump in Morro do Bumba is a result of a stereotyped view of the periphery, a view that contributes to the “favelization” of a place and one that considerably contrasts with that of residents. The positive appreciation of Morro do Bumba through oral memory that emphasizes the rural aspect of the region seems to have been discarded by the expert eye of urban planners and city officials and later by the media. We might ask why this area was chosen as a landfill site and dump in 1971? For Liguercio the “informed” views of public policy makers are supported by ideologies such as that expressed by the “myth of marginality” that tends to make the rural past, still very much present in the oral memory of the inhabitants, invisible. With the installation of the dump, a process of migration begins in the region, both internally, of the residents who lived there, and externally, of people attracted to the place, drawn to the area mainly for the use scrap iron, waste pickers, etc. Thus, the “favelization” of the area begins. With these few elements, we can see how a rural and peripheral region is gradually becoming the ideal place for the installation of a landfill. This transformation can only take place through the invisibility of a history of the neighborhood that, nevertheless, continues to haunt the emotional memory of the residents through oral tradition.

Looking specifically at the Bumba tragedy, the future disaster might have been foreseen via fleeting signs. As Roberta, school administrator at the Bumba public school Sebastiana Gonçalves Pinho, explained, the methane gas from the waste escapes from castor oil plants in a beautiful trickle of smoke.14 The skin and health problems in general that affected the population during the activity of the landfill and continue to afflict the residents after its closure act as inattentive signs of the perennial presence of toxic waste that leaked under the houses. During the first landslides, houses collapsed into the dunes inhibiting the evacuation of gases and thereby increasing the likelihood of further explosions. During the night of April 7, great confusion reigned and the signs were difficult to interpret. Total darkness and smoke made it impossible for the inhabitants to find their way. The sounds were misleading, such as the “psssh” heard by Joanir Felipe, who lost his wife and mother:

My wife accompanied me with a flashlight and I went up to the terrace of my house. I stood at the door talking to two neighbors while the guy was taking care of the power cord. It is a story of a few seconds, I heard a noise, like a tube exploding, psssh…15

As Roberta points out, during the night these sounds turn out to be crucial to the residents’ survival: “it was all black, everything was dark, you couldn’t see anything, it smelled really bad, you couldn’t see things and people were screaming, you heard screams”. It was impossible to know exactly what was happening and, therefore, to orient yourself correctly. Many of the residents find themselves caught by a misunderstanding that blurs their orientation on the hill, as Roberta tells us: “When there was a first explosion, those who went up the hill were saved by [what would have normally been a fatal] mistake, those who went down died because there was another explosion that caught everyone that went down.” Long after the tragedy, the smells of methane gas penetrated the entire neighborhood, continually accompanying the search and recognition of the bodies. The houses were quickly swallowed or covered with mud, there was nothing left, neither walls nor furniture. It is sometimes very difficult to carry out recognition when all the material goods of some of the residents have disappeared completely. In addition, many of the houses were not officially registered.

The Maelström Model and Ecopsychology

These various examples show how the situations of heavy rains and landslides, now occurring more and more frequently, bring into play questions of how one orients oneself, both within the chaos as experienced by the residents during the drama and for those who try to observe the event and learn from it afterwards. The sailor’s adventure in the maelstrom, as reported by Poe, gave rise to a model that focused on a particular problem: that of the fisherman’s mental representation of his environment at risk. While the boat follows a trajectory entirely dictated by the dynamics of the concentric currents and cannot be diverted from its course, the fisherman confined in this abyss in motion has, a priori, no other option than to observe the scene. The challenge is to discern salient elements within the a priori chaotic spectacle of these innumerable pieces of debris that surround it, to recognize these elements each time they pass in front of them, and thus be able to begin to study their trajectory. As an investigator, he observes and compares, tries to anticipate these trajectories and deduces a logical model from them. He then realizes that objects approach the center of the vortex more or less quickly depending on their size, mass, and shape, which will finally allow him to deduce that a small, cylindrical object – like a barrel – is the one that descends less quickly.

In Involvement and Detachment, Norbert Elias uses the story by Edgar Allan Poe to build a sociological theory of unplanned processes. Elias proposes to analyze the relations between nations during the Cold War and the possible drift towards an atomic war, not as intentional actions of one or another of the hegemonic nations (United States and USSR) but as the dynamics of unplanned processes from which it is impossible to escape without resort to distance. For the sociologist, the “fishermen’s parable” means the interdependence of danger and emotional reaction. It is only by distancing oneself, as much for the nation state as for the sociologist, that the double bind in which the actors/fisherman are caught can be understood.

This discovery echoes the work of eco-psychologist Joanna Macy. For Macy, the sailor’s despair is characteristic of our contemporary condition: “Nobody is exempt from this pain, any more than one could exist alone and self-existent in empty space. It is inseparable from the currents of matter, energy and information that flow through us and sustain us as interconnected open systems.”16 Like Norbert Elias, Macy believes that we are prisoners of cognitive prejudices, especially since we cannot believe what is happening to us, since environmental disasters are often invisible, inaudible to most of us. Psychologists are prisoners of a Freudian and individualistic prejudice where environmental fears are interpreted as individual neuroses. But unlike the German sociologist, for Macy, it is through the acceptance of our fears in the face of environmental risks and the articulation between emotions and reason – and not through the detachment of emotions from reason – that we can hope to find a collective way out. It is walking with this pain, through this suffering, that we can move from a power over to a power with nature.

Another American environmental psychologist, Carolyn Baker focuses on helping people prepare emotionally for the next “collapse.” The landslide in Morro do Bumba – literally the collapse of houses one on top of each other – is a sign of the gradual “collapse” that is sweeping our societies at the political, social, and ecological level. Both in Navigating the Coming Chaos and in Collapsing Consciously, Baker tries to identify different ways of preparing and adapting to increasingly frequent crisis situations. For Baker, “if the collapse means anything, it is a planetary immersion in a whirlwind of paradox.” To this end, she argues, it is necessary to become familiar with emotions and inner resources. It is even death itself that one must get used to, allowing oneself to go to the bottomless abyss represented by the fall of industrial civilization:

The fall of industrial civilization is pulling everything down, and I wonder what would happen if, instead of resisting, we surrendered to this downward movement. Am I suggesting that the collapse is a bottomless pit of dissolution? Absolutely not. But before we look at the upward movement, we must first see how to get through the collapse … the way out is through, not over or around, but through. It is crucial, however, to remember, after we have descended and restarted, that another descent will be inevitable one day.17

If on the one hand for Carolyn Baker there is no other future but the collapse of our thermo-industrial civilizations, that the consequences can prove fatal and that it is urgent to prepare for it; on the other there is a joy for the psychologist that invades us when we drop the pieces of our ego and embrace this new path. Far from the positive thinking that plagues our societies, joy accepts our necessary role in darkness. Yet, it is difficult to see any joy in the Bumba tragedy. However, there is one character who maintains a special relationship with Morro do Bumba, with garbage, and with the neighborhood: Seu Hernandez [T.N Seu is short for Signor, a colloquial sign of respect for a senior citizen]. It is after a first “collapse,” the personal loss of his beloved wife, that this man develops a special relationship with Bumba, with the tragedy, and with garbage. Special because this relationship is full of joy, a subtle emotion that, for Baker, can only arise after going through the whirlwind, whether personal or environmental. Joy is accompanied by gratitude for what you have and what has been going on. It creates in a unique way the relationship with things and beings giving access to a certain intuition, even a premonition, as is the case of Seu Hernandez and his vision of tragedy in a premonitory dream:

It’s all a dream about the garbage that I decided to write: I was there, in the garbage, and the garbage asked me:

– Who’s here?

– It’s me, it’s me.

– And what are you doing here?

And then I said:

-I came to get experience, wisdom for me, to see if I can save ecology because I need to save ecology in some way, we need to win because this fight belongs to all of us.

I saw Bumba exploding in my head, I saw all the garbage coming down, invading like houses, but is it just imagination? I took another look, but nothing. Then everything really happened, if I had told you, someone would have called me crazy, but eight days later at around 20:40, for about 20 minutes I think that everything exploded, everything collapsed, the garbage, all the houses. They said that 32 people died, but there were many more people in the middle of the garbage, that they had no time to remove because the trucks were in a hurry to remove the debris, but even so, one could see the legs of a person in the middle of the garbage who had been thrown into the truck, they were really in a hurry … Why the rush, when everything had already happened.18

From Tool to Form

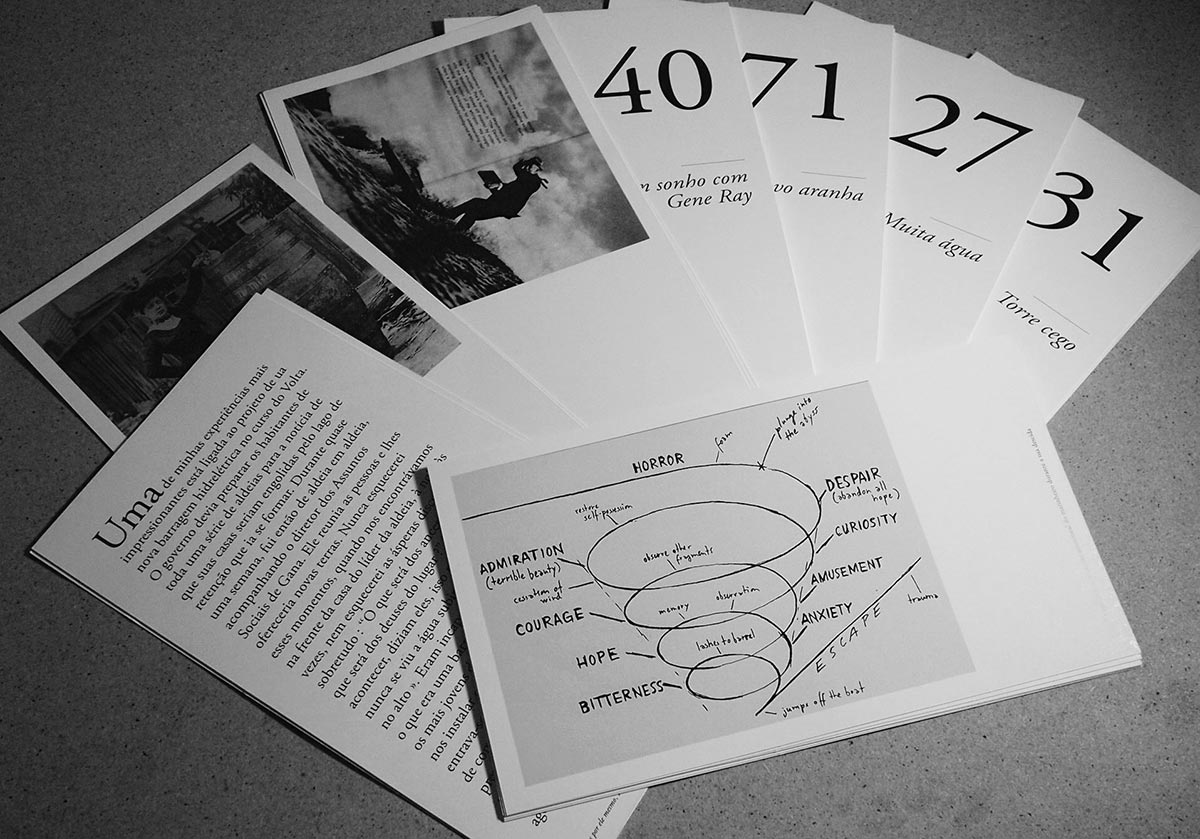

If, as Carolyn Baker prophesies, “the collapse will impose unprecedented limits on the human species and force a descent into the underworld of emotional and spiritual initiation”,19 how can the contemporary artist intervene, if not observing the treasures of resilience developed by populations responding to extreme environmental events? The model proposed by Poe’s tale, through the emotional journey that it proposes, as well as through the attention to its environment that it imposes, presents itself as a possible model of the emotional preparations that we will have to go through in order to prepare for the chaos that is to come. The abilities to hear the warning signs before the catastrophe and in the eye of the cyclone need to be shared collectively. It is with this in mind that we developed the project A tale as a tool, as activations of investigations that involve the collective and more particularly the people and witnesses found during our investigations. The creation of a deck of cards featuring information from our research and the reading of these cards and of Poe’s tale in discussion groups allow us to share our thoughts and experiences regarding both personal and environmental tragedies, for which each one of us was able to develop our own skills and abilities, or even make our own “barrel”, in the manner of the sailor in Poe’s story.

We managed to create several possible means of activation during the several occurrences of the project: conversation groups, reading groups, floating assemblies, research offices. But we can imagine others such as an itinerary, a ritual, an exercise in vision, collective meditation, a meal. What value should we give to these forms? For French art historian Estelle Zhong, an artist who produces what she chooses to call a “common art project” – that is, projects that involve the participation of people from different backgrounds – “chooses the conversation of materials, reconstruction, [meals] due to their implicit latent forms that [in turn] have decisive formal consequences: this is their artistic competence.”20 In this analytical framework, the ethnographic descriptions and data collected during research, but also the technical gestures, interviews, conversations, and readings, give rise to certain implicit forms that the artist may identify. Most of these materials are materials that, a priori, are not intended to take on a specific form. The production of a certain number of assemblies, of collective marches, allows the production of forms that generate diversified supports, for interpretations in movement. During these assemblies, through a protocol that is often quite simple, we suggest that the participants take up the testimonies and files collected in order to gather them and use them as a basis for awareness and “spiritual preparation for the collapse of the civilization that we know is raising our awareness to the every day ‘small collapses’ of civilization that we can already see around us.”21

I proposed Edgar Allan Poe’s story as a tool to navigate into the heart of the “small collapse” represented by the landslide of Morro do Bumba. The tragedy that occurred in April 2010 highlighted the “haunted” character of Morro do Bumba and the development of specific emotional skills required to adapt to it: it is accepting to dive into the heart of the negative emotions that our environmental future causes where we will be able to create resilience to help us overcome it. Those who have already experienced these “small” deaths, whether they are psychological or ecological, will be much better equipped to deal with the “chaos to come”. Poe’s story together with the specific case of Bumba allow us to point out resources for guidance and prediction that are not limited to scientific and technical knowledge, but also include a certain practical knowledge of the terrain of life, an affective memory of place and the ability to accept what dreams have to teach us.

For more information: www.ataleasatool.com

***

Sandrine Teixido

Author, artist and anthropologist. She teaches anthropology at the Jean Jaurès University in Toulouse (France). She created the project “A short story as a tool” with the Swiss artist Aurélien Gamboni in 2011. She published an ecofeminist rewrite of Edgar Allan Poe’s short story with Cambourakis Editions (published in February 2011).

1 Anna L. Tsing, The Mushroom at The End of The World. On The Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University 2017)

2 Edgar Allen Poe,[1841], The Fall of The House of Usher and Other Writings (London: Penguin classics, 2003)

3 The reported numbers of deaths, missing and homeless as a result of the tragedy vary considerably. The lack of confirmation only serves to reinforce the continuing emotional and social impact of the disaster and further underlines the absence of state responsibility. For the purposes of this essay the following references were consulted: “Morro do Bumba: triste símbolo do problema do lixo” Revista em discussão, 2010, available at: https://www.senado.gov.br/noticias/Jornal/emdiscussao/revista-em-discussao-edicao-junho-2010/noticias/morro-do-bumba-triste-simbolo-do-problema-do-lixo.aspx (acsessed March 2021). Another source of research: João Francisco Canto Loguercio, “Morro do Bumba, Ethnografando a transformação de uma paisagem sob múltiplos olhares”, Mestrado, UFF, 2013, p. 4

4 Marshall MacLuhan & Quentin Fiore, The Medium is the Message (New-York: Bantam Books, 1967).

5 Norbert Elias, Involvement and Detachment (Blackwell Publishers, 1987)

6 Bruno Latour, Down to Earth. Politics in New Climatic Regime (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018)

7 Citton, Y., Rasmi, J. Générations collapsonautes: Perspectives d’effondrements (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2020)

8 I would like to take this opportunity to thank Michelle Sommer for her knowledge and enlightened advice that led to my meeting with Luiz Guilherme Vergara and Jessica Gogan and their support of the creative process.

9 Tsing, A et al., Arts of living on a dammaged planet. Ghosts and Monsters of the anthropocène (Minneapolis:University of Minnesota Press, 2017)

10 Loguercio João Francisco, Morro do Bumba, Etnografando a transformação de uma paisagem sob múltiplos olhares, Mestrado, UFF, 2013.

11 Larrère, Catherine e Larrère, Raphaël, Do bom uso da natureza. Para uma filosofia do meio ambiente (Instituto Piaget: Lisboa, 2000 (1997)).

12 Loguercio, 2013, p.30

13 Pereira Vilma, 2018, Desastre Ambiental: Comunidade Morro do Bumba-Niterói, RJ, Auto-edição, Amazon.

14 Interview, November 2019 Escola Sebastiana Gonçalves Pinho, Niterói.

15 Interview Joanir Felipe, June 30th 2017, Rancho Verde, Niterói.

16 Joanna Macy, “Working through environmental despair”, in Ecosychology, Roszak, Gomes, & Kanner, eds. (Washington: Sierra Club 1995) p.2.

17 Baker, 2013, op. cit., p. 62-66.

18 Interview Seu Hernandez, October 2016, Rancho Verde, Niterói.

19 Baker, 2013, op. cit., p. 141.

20 Zhong Megual Estelle, L’art en commun-Réinventer les formes du collectif en contexte démocratique (Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2019) p. 67.

21 Baker, 2013, op. cit., p. 48.