The cultural environment becomes visible. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

Encounters and Detours: Affective Cartographies of the University of Quebradas

Angela Carneiro

For Beá Meira

You put together two things that have not been together before. And the world is changed. People may not notice at the time, but that doesn’t matter. The world has been changed nonetheless.”

Julian Barnes1

What can an encounter make possible? A memorable encounter is powerful when we don’t leave the same as we came in, when what happens reinvents us and reinvents what’s around us. This risk – because it is a risk to willingly enter the detours of life – exists when we walk on the edges of our worlds and insist on crossing frontiers that are not yet named. But such a risk invites passage, like a kind of tightrope walking, tentatively feeling the unknown, believing in a network where only our inherited stories, remembered and forgotten, give us assurance, at times firm, at times unsteady.

The University of Quebradas (UQ), in an extension course lasting one year and now in its fifth edition, takes up this challenge. Coordinated by the professors Heloisa Buarque de Hollanda and Numa Ciro, it is part of Programa Avançado de Cultura Contemporânea (Advanced Program in Contemporary Culture or PACC) of the Department of Literature at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Quebrar in Portuguese means to break, and the course focuses on knowledge production via an encounter between the academy and artists, cultural workers and poetic activists who live on the periphery and who see themselves as “quebradeiros” (literally those who break), circulating in and out of the fluxes and margins of the city. The course name has its origin in the word used for a favela (city slum) in São Paulo. Favelas with their labyrinthine alleyways and narrow “breaking” paths form a very unique cityscape, aptly describing life that insists on making its way. Quebrada also suggests a critical attitude to life, a necessary breaking down of the absolute and imposing paradigms of domination and power that define places of value and belonging.

This essay explores these “quebradeiros” processes and focuses on the experimental work of the recent fourth edition of the UQ where we created a working group to develop a poetic reflection on the most pressing issues that concerned class. The text follows key moments established during the process: First, the Quebradas of MAR, when the course moved to be held at the Museum of Art of Rio de Janeiro (MAR); Second, when the quebradeiros expanded MAR’s relationship to the city to produce a new cartography between the city that dreams (Manifesto) and the city that you live in (Map), made by the multiple rivers that flow into the Mar. (MAR here is the museum and then mar meaning sea in Portuguese); And thirdly, when the Manifesto and the Map were miniaturized to create “messages in a bottle” and thrown into the sea and tracked in their travels. Finally, some reflections on the methodology of the work will be discussed.

UQ’s work is constructed in the search for a space between academia and the quebradeiros, an “in-between” that welcomes different modes of knowledge and methodologies and that is able to accommodate and expand on academic discourse as much as that of the quebradeiros artists to imagine other forms of knowledge production and sharing.

In this tension, the periphery arrives making noise, pulsating with an intense production of culture, punching holes in the mass media image of aridity and lack, showing culture as a process of social construction of reality and of designing ways of life and occupation of the city. On the other hand, the academy seeks its own noise, the reinvention of a knowledge discourse that has staying power because it is used by many. From this encounter, new paths arise. A bet.

And what do the quebradeiros bring?

They forcefully demonstrate art making as an invention of life, as a meaning-making generator that reorders ways of life, empowers the legacy of different origins and redistributes the concentration of cultural goods by other logics of production, questioning the very society in which we live. This attitude recalls Homi Bhabha’s notion of culture, which points to a production of subjects in the spaces in-between, in the strange gaps, slippages and the marginal.2 Quebradeiro-making occurs at the borders, in transitional spaces, and emerges as a combative dialogue between what is imposed as the only and absolute reality and new ways of life supported by practices that constitute an ecology seeking other ethical, aesthetic, and political parameters. Here is its strength: to think what – from the outside – demands speech.

Quebradeiros territories serve as analyzers of the city we live in. They raise many questions centered around the problematizing of the concept of culture as a tension between a culture that responds to the logic of the market which as entertainment, is reduced to consumption, and another culture that seeks the reinvention of reality, questioning the very concept of center and periphery. In this force field, a constant critical attitude toward the cultural industry and its institutions that co-opt this artistic production to justify their existence, is fundamental.

For us, then, what is constantly present are the ebbs and flows of creation and reinvention in a city where most people live in areas with little or no cultural resources – cinemas, theaters, cultural centers, libraries – but where there is an intense cultural life. Cultural and social activities (soirees, movie clubs, dances, a rich gastronomy, various workshops), artistic groups (musicians, poets, graffiti artists, theater and film groups) are generally invisible to a media that maintains a focus on violence and dilutes the complexity of the multiple relations that make up a city in flux.

Quebradeiro territory also means the presence of innumerous religious groups that, while preserving a rich cultural heritage, can also be intolerant of others, particularly, with the growth of new churches.

This territory also means the increasingly complex presence of the Police Pacification Units (UPPs) and the long struggle ahead of trying to live with them, as they oscillate between the rule of law and barbarism.3

On a daily basis, being a quebradeiro implies the difficulty of mobility in the city for those who live in it, where long trips in degrading conditions are the norm.

It’s a rich production of narratives that go beyond social networking sites that are documented in books and videos; these productions are based in another economic logic, grounded in creativity, solidarity and pressure on governments. It means thinking about creation beyond a work of art, more as a paradigm of a way of looking and of embodiment within the body of the world.

What can we do to ensure that time inhabits these questions in order to multiply them into others, so that they don’t lose their vigor and can create other possibilities?

The Quebradas of MAR

With this basket-full of concerns we faced a wall, but from there, a path formed.4 Again, the University of Quebradas was homeless. Adrift, the Museum of Art of Rio de Janeiro (MAR) welcomed us – a promising encounter.5 The institution is situated in the city center, in the port region, an area that has a rich historical tradition and culture, now experiencing complex economic and political changes as a result of renovation projects and gentrification. And so, new questions came into play and increased our restlessness. What would it be like to occupy this new space, to shift from the academy to the museum? As a place for events what can a museum make possible? How could we keep the tension between us in play so that differences did not become diluted, but worked to bring us closer?

The basket of issues continued to expand. How to fully engage with the processes taking place there, yet stay clear of the co-opting that immobilizes and ends up reproducing the same? Here and there, some quebradeiros formulated new questions. How could they appropriate other languages for new thought compositions? We decided to focus on what the quebradeiros bring, in the luggage of their territories of origin, which may contribute to expand the knowledge about the city of Rio de Janeiro. Would it be possible to redesign the city culturally and expand its borders for a production that housed a multitude of expressions? How could this encounter redraw the city?

The cartographers call on the class. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

To dive into this more deeply, a group of quebradeiros became interested in forming a working group (Angelo Mello, Denise Kosta, Fábio Pedroza, Juliana Barreto, Noelia Albuquerque and the professors Beá Meira, Angela Carneiro and Egeu Laus) and met weekly over the course of one year. Throughout this period, a dialogue was constructed between the working group and the class of 70 students, and together they produced a new composition. For example, they created the Quebradeiro Manifesto, discussed later.

It was a very special moment. With the preparation for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics, the city had become a huge construction site, which greatly increased the difficulty of circulation and generated a climate of growing dissatisfaction, to which was added the news of construction expenditures for sporting events, revealing the huge mismatch with respect to the distribution of investments in health and education. Brazil went to the streets and confronted the Brazil made in cabinets. The great slogan “You do not represent me,” that emerged from the streets, exposed the crisis of representation, and that the country required change. Social networks were the mechanism, the fuse, which triggered a movement, a crescendo, that exploded in a series of demonstrations that took to the street, not only in Rio de Janeiro, but throughout Brazil. On the largest day of mobilization the streets of the country were occupied by more than one million people.6 Furthermore, in Rio de Janeiro, the situation worsened, when what was already present in everyday life in the periphery – violence, lack of rule, disregard for people – and the complex situation of the UPPs – not only to be seen as police action, but also a State policy of re-territorialization – made more and more evident the contradictions that exploded with the disappearance of the odd job builder Amarildo inside a UPP headquarters and the imprisonment and death of the nurse Ana Claudia, both victims of police violence.7 The city was hit as a whole. All this together reverberated in other territories and a collective force field was activated.

What were the effects of this scenario on the Quebradas? The quebradeiros have inscribed in their bodies the pain and absurdity of a divided city and they assert a time of change is at hand. They speak of the city that they want. In a collective action, they worked with Professor Sandra Portugal, from the Laboratory of Speech and Language, using the narrative form of a manifesto.8

Sandra Portugal discussing manifestos. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

They explored: What is a manifesto, what is its relationship to the present and the desire for utopia? What are or were diverse examples of manifestos and interventions in society? Does a manifesto have the ability to trigger a field of collective forces?

The 4th year class of Universidade das Quebradas. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

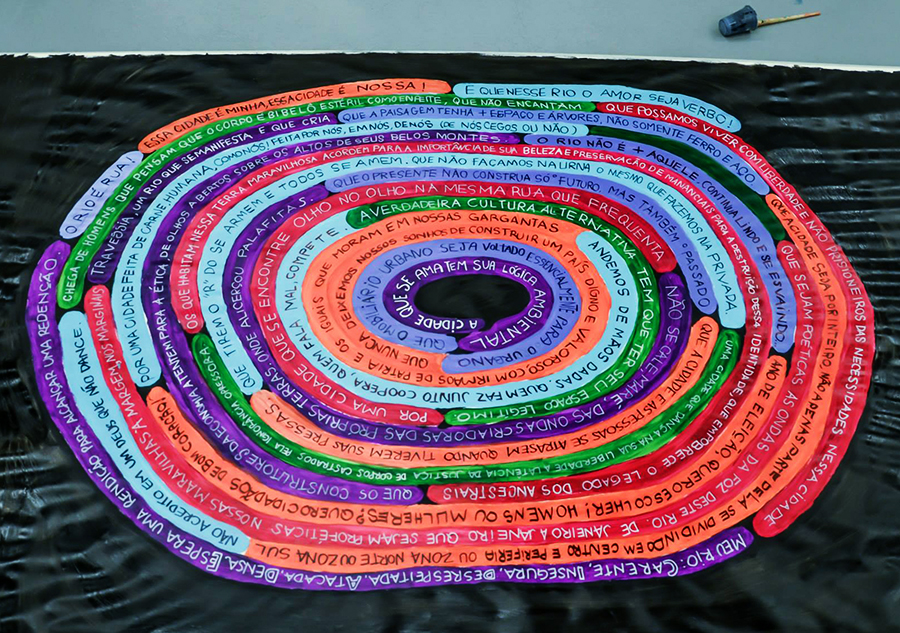

To grab hold of the word and not expect it to be given was the fundamental shift that made this encounter memorable. As a result, they launched the Quebradeiro Manifesto, a large hand printed multicolored labyrinth looking for exits, not by the path of more of the same, but by what could truly be untested. By the word expressed in gesture, the Manifesto affirms the city we want.

Multicolored labyrinth of desires. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

The manifesto. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

Quebradeiro Manifesto

• A city that loves itself has its own environmental logic.

• That urban street furniture should be primarily focused on the human.

• That we never give up our dreams to build a worthy and valiant country with brothers of this land and people like us that live in our throats.9

• Let us walk hand in hand. Those who make together, cooperate, those who speak ill, compete.

• True alternative culture must have its rightful space.

• For a city that meets itself eye to eye on the same street it frequents.

• The tide will not be silenced, from the waves of the creators of its own lands. Where houses on stilts were founded.

• That the present not only builds the future but also the past.

• That cities and people are late when they are in haste.

• How to take the “R” from those that arm themselves and that all love one another.10 That we do in the ballot box what we do in private.

• A city, that dances in its freedom, the latency of bodies castrated by an oppressive ignorance.

• Those who live in this wonderful land wake up to the importance of its beauty and the preservation of its resources, and the destruction of its identity, which impoverishes the references of the legacy left by their ancestors.

• That the builders of the economy pay attention to the ethics of justice, with open eyes to the tops of the city’s beautiful hills.

• Rio is no longer what it was, but continues to be beautiful and to fade.

• Election year, I want to choose! Men or women? I want people with a good heart.

• For a city of flesh, human, like us. A city made of us, for us, in us (from us blind ones or not).11

• Love the art that sees the open sea.

• That the waves at the mouth of this river be poetic. That, from January to January, our marvels at the margins be prophetic. We, the marginal.

• Crossing, for a river that manifests and creates.

• That the landscape has more trees and space, not only iron and steel.

• That the city be a whole, and not just a part of it, dividing into center and periphery or north zone and south zone.

• Do not believe in a God who does not dance.

• Enough of those who think that the body is sterile as figurine ornament, who are not enchanted.

• That we can live freely and not as prisoners of needs in this city.

• My Rio: Needy. Insecure. Disrespected. Attacked. Dense. Waiting for a rendition to achieve redemption.12

• Rio is the street.

• This is my city, this is our city.

• And that in this Rio love is a verb!

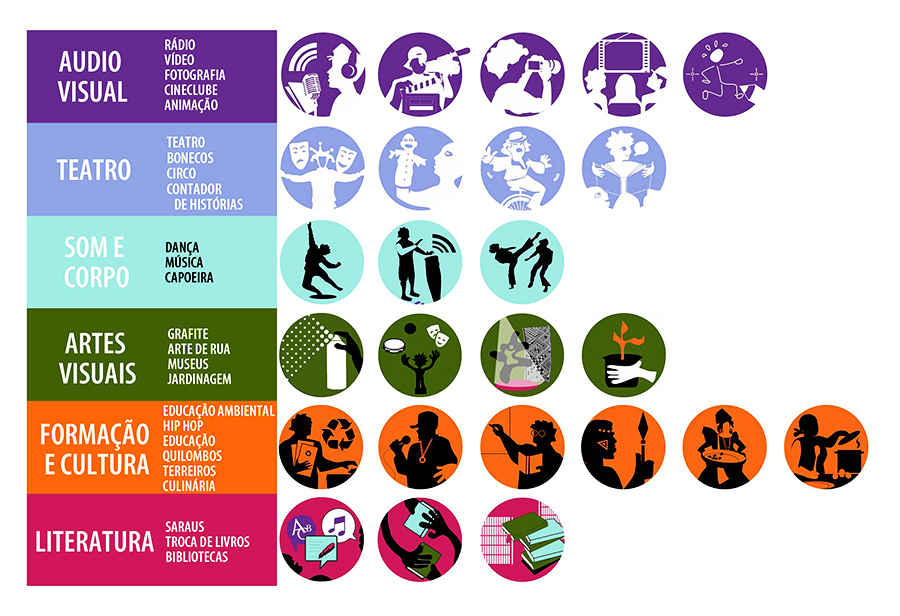

The Manifesto, the city that we want, affirmed the city we live in. Where it seems nothing happens, it is there that the class focused, drawing on a wealth of culture and political knowhow that seeks change for those who live on the periphery. In order to register this production, the working group together with the class researched and developed a series of icons that dialogued with the wealth of expressions from the periphery and forged a new cartography of the city, showing the multiple cities that inhabit the Rio de Janeiro in a map.

Map legend icons. Photoshop art: Beá Meira.

The Rivers (Rios) that flow into the Sea (Mar)

In this process of redesigning the city, water emerged as a strong element, for its fluidity, resistance, and maleability. It carries stories, songs and rhythms, drinks at the well of the ancestry and transforms into The Rivers that flow into the Sea. We want to know what flows in the memory and body of each quebradeiro. We understand that the work of each one in their territory is a way of expressing multiple crisscrossing connections that constitute personal relationships. These are the relationships that will give body to the map and break international convention. Maps of Rio de Janeiro, in general, are the tourist maps that show the city from the beach and the south zone. The quebradeiros map disconcerts because the north is no longer a reference, replaced by the railroad that comes from Santa Cruz and by Avenida Brazil; it is the west zone that reorders the city.

Following the train line. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

And the map brings with itself the wonderment with the world that emerges from the colors, flavors, rhythms, beliefs, inventiveness, tradition, solidarity, knowledge, and layers of time talking about this present in the midst of so much trouble. The naked map is taken by each quebradeiro, giving visibility to a cultural activity identified by icons and the circulation and participation in different centers of the periphery. These icons create a cultural environment interwoven with a life, damned, difficult, of one who is impelled to being leftover in the world.

Starting with a new map. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

De-northing the map. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

Bottles to the Sea

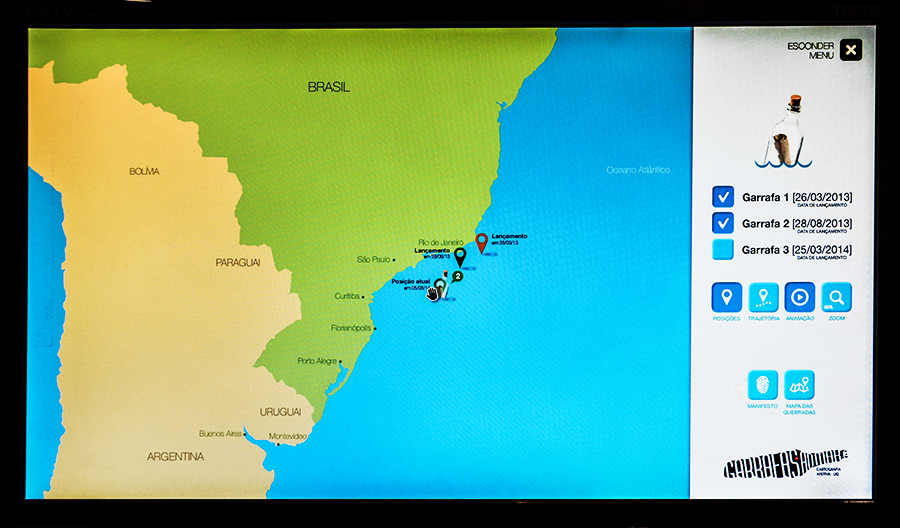

With the Map and Manifesto in hand, ideas took shape. Miniaturized, map and manifesto became messages in a bottle to be thrown out to sea;

Bottles into the Sea. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

Like a ritualized ancient tradition of carrying the distress of castaways or the desire that something precious will find a destination. What to expect?

A precise desire finds its destiny. Photo: Beá Meira.

Adrift, fragile, subject to the unexpected, against the flow of scripted and safe trips so much on offer these days. Promises of future in the here and now. We, the quebradeiros cartographers know that mapping is always partial and provisional, nothing more than a flux of moments that already advertises other landscapes, bypassing networks and constant forms of attention-grabbing. For this, re-launching is the modality, letting go is to open up to new forms, a way to accept the risks of chance, follow them, but without having control over them, go with them, share our experiences with other peripheral groups or individuals, find new partners, extrapolate our borders. But, even if it was a gesture in the dark of the possible, the idea to accompany this trip, without being able to influence it, fascinated us. How might we follow these bottles on their journeys?

Three bottles on their journeys. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

The contemporary technologies of the Laboratory of Computational Methods in Engineering (COPPE/UFRJ), coordinated by Professor Luiz Landau, gave us the conditions to monitor the journey and the flow of marine currents by satellite. The bottles are equipped with local sensors (surface drifters, profilers and seagliders) and remote sensors connected to orbiting platforms that record the flow of ocean currents.13 Certainties, none. In the endless sea, our frailties gained poignant visibility and, a poetic immersion, they carried a deep desire of encounter that transforms us and transforms the world.

Revisiting the process, we realized that looking back allows us to mark the points made along the way. We realize how difficult it was to overcome the biggest challenge, that is, working with what is not in the mirror. Moving forward for us meant confiding, listening, negotiating, supporting, not knowing, leaving known perimeters for an ex-peri-me-action of self and the world.

Cartography contributions

Cartography as a method aims to follow connections, detours and processes as they invent pathways. The choice of this methodology is grounded in the belief that reality is in a constant process of production and that it is possible to construct territories that welcome the differences that arise from the multiple possibilities of encounters, or in other words, from the interest of thinking from/within trans-form-actions.

In our case, cartography allowed us to look back and identify what, for the group, were the moments and conditions that led to the path that was taken. We had issues, anxieties, and different languages but not a path. For us, cartography enabled a field of forces where interest was focused on the compositions of objects, not their representations. Different from mapping, cartography follows movements as a continuous happening, an endless process of inventing worlds that make and unmake the landscape, always in a way that is provisional and partial.

As a method, our use of cartography drew on the result of studies by a group of Brazilian researchers who, inspired by the work of Deleuze and Guattari, articulated some pointers as to how to use it.14 They explained: cartography is not a readymade method; it demands of the cartographer an attention which, rather than being focused on something, is open to the unexpected; it is constructed collectively via the composition of forces as a way out of the dichotomy between the individual and society; it works to dissolve the notion of the observers’ points of view in order to highlight the implications of their presence in the field; and employs a narrative approach, resulting from taking a position where one faces oneself and the world, a talking “with” and not “about” events. Cartography renders the dynamics of a moment, generates a version of the world drawn from encounters, but, as encounters are always on the verge of happening, cartography focuses its attention on transformations. And brings us to a new question.

What do we bring into existence when we produce this work?

First, certain is an experiential knowledge production that leads towards the emancipatory potential of activities, which in turn brings us to the concept of the emancipated knowledge of Boaventura Sousa Santos.15 The author considers emancipatory, knowledge that thinks of the consequences of acts in which the subject-object relationship is replaced by reciprocity between subjects in relations of solidarity. This forms a space that, according to Spinoza, enables good encounters, those born of affections infused by joy, as the experience of allowing oneself to be affected by intensities that expand life.16

Good encounters. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

Second, looking to the processes that were established between us, we sought to actively deconstruct hierarchical relationships and to affect a coordination of the group based on an ethical practice of listening to the other, who walks with and not about the other. This other, who is not passive, causes discomfort and puts us at risk of being destabilized. It is in this tension that we make room for new knowledge.

Third, to create is to find a work that is constituted via a web of encounters: ways of life, differences that come together, words, but also, silences. We left behind dichotomies and worked with the inclusive, in a constant game of it’s this, it’s that, and more this and that other. It is in the game of encounters with human beings, but also in how our body allows itself to be affected: an image, an object, a sound, and a scent that leads us astray. Or in other words, we expand ourselves in the multitudes of encounters. A field of events, much more than what happens, but what happens to us in a poetic encounter with the other, the order of the rare and singular.

Fourthly, this is a work that calls for body and time, knowledge mediated by the body, an expanded body, that looks at the entire body, which can reinvent itself and also think with its skin, see with your ears, touch with the eyes, and dwell in the spaces of time. And thus, extending boundaries on the heels of what varies, in the cracks of everyday life. Especially, where they tell us that nothing happens; this is exactly where we focused our attention. Making time meant inventing what we called conversation bubbles, spaces of encounter, a place of questions that only happen when we empty ourselves of reproductive sameness. We needed to listen to what was invisible, but no less existent. Plan each encounter according the clues they offered us, aware of what could become an obstacle, and turn it into a possibility. For example, one day the group was marked by a tragedy: a major highway footbridge collapsed, people died and the city fell in on us. On that day, the conversation was difficult, because the footbridge was part of the regular path people used. However, the footbridge established a great dialogue about the city itself and brought forward the tension: what can be a bridge and what can be an abyss, what cuts and what approaches? In this way, we think our methodology is made in the encounters, it is to become (to happen), via the bonds created between us, in which differences form the material of approximation. From all this, we made devices to register the dialogue: paper, charcoal, paint, balls, cloths, drawings, water, texts, movies, music, words, sea, programs, animations, stickers, and photos.

![GARRAFASsemfundo [Converted]](http://institutomesa.org/revistamesa/edicoes/2/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/foto7.jpg)

Tracing Brazil Avenue with acrylic paintbrush. Photo: Beá Meira.

![GARRAFASsemfundo [Converted]](http://institutomesa.org/revistamesa/edicoes/2/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/foto8.jpg)

Stickers. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

![GARRAFASsemfundo [Converted]](http://institutomesa.org/revistamesa/edicoes/2/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/foto9.jpg)

Writing with charcoal. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

Throughout, the testimony of Hélio Oiticica given to Ivan Cardoso in 1979, reprinted in the book Encounters, resonated with us. An encounter with art as invention is what points to a radicality of making art: “I did not become an artist, I became a declanchador (trigger, generator) of states of invention (…) the state of invention is profoundly lonely, but it is profoundly collective.”17 The artist as a catalyst of collective force fields. Amidst these fields we embroiled ourselves.

A powerful device that supported us along the way was the use of social networks. It vitally enabled us to maintain a continuous communication channel, reducing the distance and the time between encounters. Similarly, we needed to understand studying itself as a device: the sharing of issues and mainly supporting the necessary continuity of our work as a practice in process.

Finally, the Bottles in the Sea relaunched the idea of knowledge as a production with the other and not about the other. To not lose motion, you need to relaunch, seek boundaries that allow transit. The bottles in the sea, with their poetic dimension, involved us in the movements of expansion and contagion in search of more encounters. Where more than arriving, what interested us was the journey and the ability to produce narratives that carried multiple meanings of possibilities for invention. Chipping away at the impossible, we invented worlds, perhaps more beautiful and in solidarity, pausing where intensities dislocated us. And so on, we go on.

![GARRAFASsemfundo [Converted]](http://institutomesa.org/revistamesa/edicoes/2/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/foto21.jpg)

Our desire for encounter and transformation. Photo: Noélia Albuquerque.

_

1 Julian Barnes. Levels of Life. London: Random House, 2013, p.3

2 Homi K. Bhabha. O Local da Cultura. Trad. De Myriam Ávila, Eliana Lourenço de Lima Reis, Gláucia Renate Gonçalves. – 2ª Ed.- Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2013, p. 19-20

3 Starting in December 2007 Pacification Police Units (UPPs) began as a police intervention project developed by the Secretary of Public Security of the State of Rio de Janeiro aiming to regain state control over favela communities that were under the influence of armed criminal groups and to bring to the local population the peace and tranquility necessary for the performance and development of full citizenship. To date, 39 UPPs have been installed in areas that encompass communities mostly in the south, center and north of the city. The project is very controversial due to a series of challenges within the police force as a result of corruption, violence, abuse of authority, and not reaching quotas. On the one hand they have the approval of many of the communities served, where people have experienced a reduction of violence in their daily lives, and on the other the disapproval of residents who found themselves involved in cases of violence committed by the UPPs, as in the case of the disappearance of Amarildo de Souza, the imprisonment and death of the nurse Ana Claudia, the murder of the dancer Douglas Rafael Pereira da Silva, among many others.

To see the map with UPP census data: http://oglobo.globo.com/infograficos/upps-slums-rio/

For More information: http://www.rj.gov.br/web/seseg/exibeconteudo? article-id = 1349728 and http://www.upprj.com/ and also the article by Silvia Ramos and Ricardo Henriques on the implementation of the UPPs. http://www.ie.ufrj.br/oldroot/datacenterie/pdfs/seminarios/pesquisa/texto3008.pdf project

4 The original text in Portuguese is “nos vimos diante de uma pedra” translated as “we face a wall” literally means “we faced a stone.” The metaphor here refers to the poem “In the Middle of the Road” by Brazilian poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade:

“No meio do caminho tinha uma pedra

Tinha uma pedra no meio do caminho

Tinha uma pedra

No meio do caminho tinha uma pedra.

Nunca me esquecerei desse acontecimento

Na vida de minhas retinas tão fatigadas.

Nunca me esquecerei que no meio do caminho

Tinha uma pedra

Tinha uma pedra no meio do caminho

No meio do caminho tinha uma pedra.”

“In the middle of the road was a stone

Was a stone in the middle of the road

Was a stone

In the middle of the road was a stone.

I’ll never forget that event

In the life of my so tired eyes

I’ll never forget that in the middle of the road

Was a stone

Was a stone in the middle of the road

In the middle of the road was a stone.”

Translation: Instituto Moreira Salles available on youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sO6TySzyygE (Accessed October 2014)

In reality, for us, the stones, our restlessness was what made the road.

5 MAR – Museum of Art of Rio de Janeiro opened in 2013 is a museum, markedly visual arts, which seeks new urban cartography and art, and works directly with municipal schools, creating relationships between students and teachers, residents and workers of the port region in which the museum is situated. MAR engages in diverse partnerships – with Brazilian and international universities, national and international museums (Museum of Modern Art – MoMA, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation), centers of cultural production, local residents and movements of collective production of knowledge, and art and collective actions. For more information www.museudeartedorio.org.br

6 http://noticias.uol.com.br/cotidiano/ultimas-noticias/2013/06/20/em-dia-de-maior-mobilizacao-protestos-levam-centenas-de-milhares-as-ruas-no-brasil.htm)

7 Amarildo Dias de Souza (1965/66 – 2013) was an odd-job and handy man who disappeared after being detained by military police headquarters in the UPP Rocinha, on July 14, 2013. http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2014/07/1480834-pm-do-rio-conclui-inquerito-militar-no-caso-amarildo.shtml

8 Sandra Portugal is part of the Education and Implementation Project of the Roberto Marinho Foundation and of the pedagogic team of the University of Quebradas. As a fruit of the partnership between the two institutions she is professor of the the Laboratory of Language and Expression of the University of Quebradas.

9 Translator’s note: In Portuguese “nó na garganta” literally means “a knot in one’s throat” meaning simultaneously the desire and the inability to speak. The original text is “os iguais que moram em nossas gargantas” literally the equals (people like us) that live in our throats. In other words voices yet to speak.

10 Translator’s note: In Portuguese se armar (to arm onself) e amar (to love) are solely differentiated by the letter R.

11 Translator’s note: In Portuguese “de nós cegos” suggests not only the blind ones (nós) but also blind spots as “nós” also means knots.

12 Translator’s note: In Portuguese the first letters of these words spell cidade (city) Carente (needy) Insegura (insecure) Desrespeitada (disrespected) Atacada (attacked) Densa (dense). Espera (wait or hope)

13 To see the bottles on their journey: http://www.lamce.coppe.ufrj.br/secao-portfolio/garrafas-ao-mar/aplicativo.html

14 Eduardo Passos, Regina B Benevides de Barros. “Diário de Bordo de uma viagem – intervenção.” In: Eduardo Passos, Virgínia Kastrup, Liliana Escóssia Eds. Pistas do Método da Cartografia: pesquisa-intervenção e produção de subjetividade. Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2011, p.173-202 e Gilles Deleuze e Felix Guattari. Rizoma. Rio de Janeiro: Editora 34, 1995. Mil Platôs: v.1, p.11-38

15 Boaventura de Sousa Santos. “Para um novo senso comum: a ciência, o direito e a política na transição paradigmática.” 3ªed. São Paulo: Cortez, v.1: A crítica da razão indolente: contra o desperdício da experiência, 2001 p.103-112

16 Baruch Spinoza. Ética: Da Servidão Humana ou das Forças das Afecções, parte IV Tradução de Antônio Simões.Os Pensadores, 2ª ed. São Paulo: Abril Cultural, 1979 p. 238

17 Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica often created his own neologisms, one of the most well known is crelazer (literally cre leisure/creative leisure). Here it seems he draws on the word declanché in French meaning triggered bringing it into Portuguese to suggest the idea of unleashing/triggering (in the sense of a gun) implying that he sees his practice as being both a catalyst for and generator of states of invention.