Meditation, art, environment and social transformation in the dry equatorial forest. Puerto El Morro, Golfo de Guayaquill, Cienega Grande, Equador. Recuperation of ancestral stone walls. Residency Franja Art Community, 2013. Photo: Alejandro Meitin

Bio-regional Initiative: A redefinition of spaces of creation and action

Ala Plástica

The following essay explores a number of critical transdisciplinary initiatives that in their very constitution and process of development integrate an artistic way of thinking and working related to art and the environment. These initiatives comprise communicative strategies and actions connected to social contexts that sharply contrast with modernist ideologies of art’s neutrality. The initiatives not only operate amidst the art world’s discursive assumptions, institutional contexts, and publics but also engage with the discourses of both art and activism, opening up possibilities for aesthetics to transcend its disciplinary confines and operative orbits, reinstating an artistic practice less oriented toward the spectator.

In the initiatives presented here, art is an integral part of a shared working process, produced jointly or in negotiation with groups, activists, and associations. Experimental communities are formed where the participants’ commitment is manifested in their immersion in the creative process, where thought and public debate are converted into the central material and constitutive core of the artistic work, which involves a social collective or sometimes all the population of a region in the staging of micro-utopias of human interaction. These constitute a cultural movement focused more on social creativity than on self-expression. The work then is constituted as an ensemble of forces and effects that operate in numerous registers of meaning and discursive interaction.

Updating technical analysis skills: Rizhome initiative, 2006. Photo: Alejandro Meitin

Ego-system

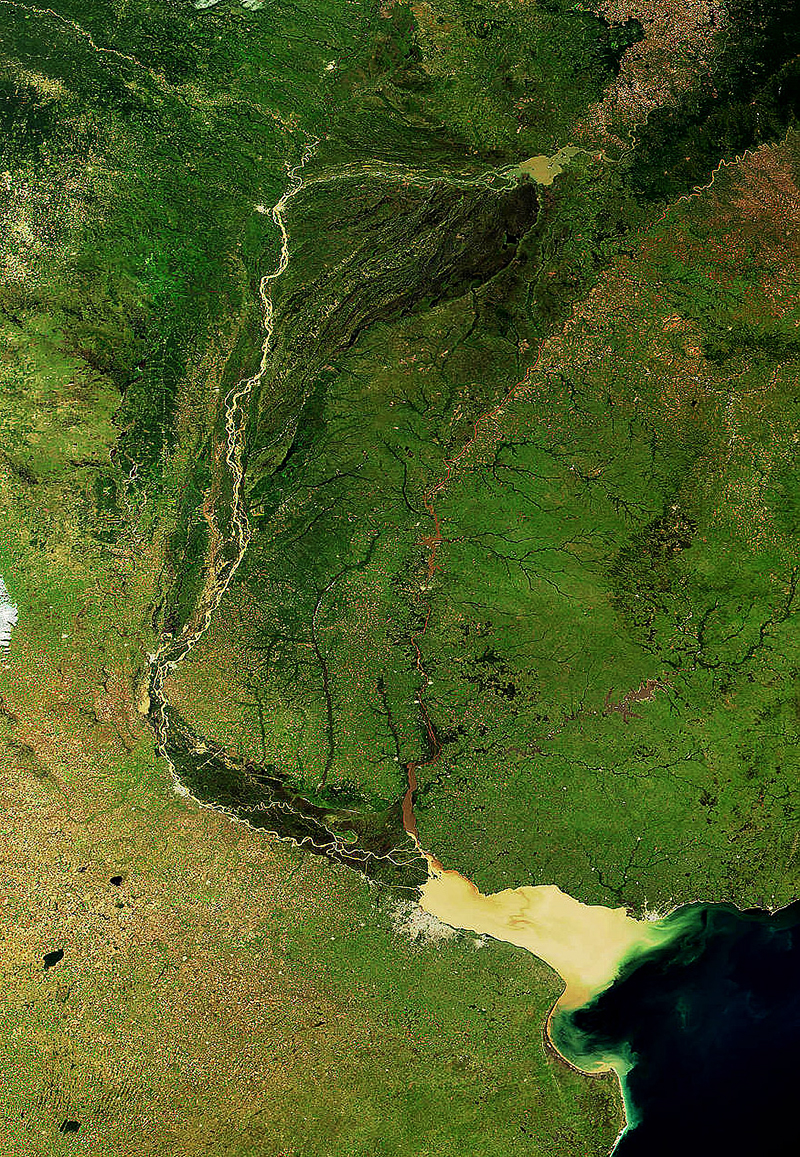

When, in the 16th century, the Spanish explorer Solís named Mar Dulce (Freshwater Sea) what is today Rio de la Plata, he made clear its natural characteristics: its duality. Solís’ river-sea is a big melting pot, where maritime and fluvial extremes meet and mix. The estuary is also the main source of fresh water for a human concentration of more than 17 million people, established in the no more than 60 km of Argentine coast in the mega-urban region of metropolitan Buenos Aires. The area has suffered massive developmental upheaval with an almost total disregard for what the uncontrolled advance of invasive metastasis causes to vulnerable and already scarce ecosystems.

The city simply expands its human demands, exerting enormous pressure on coastal ecosystems. As a consequence this unregulated expansion generates toxic social and environmental situations that have serious effects on the quality of life and health of the whole region. These effects also cause social, economic and environmental conflicts that gain little attention since they occur in the natural environment and do not directly affect the immediate urban area. Urban development in the region is such that the metropolitan centers in many cases are seen as isolated and self-sufficient societies, separated from the surrounding region, an “egosystem” that could be defined as where planning confronts humans, leaving as the only option the acceptance of these toxic and contaminated changes.

Shell oil spill evidence collection, Magdalena, 1999. Photo: Marcelo Miranda

Advanced research on immunodeficiency recognizes that the human body is connected in a kind of neurochemical communicative network with its surroundings, which largely determines our health and well-being. Communities identify with environmentally recognizable systems via a comprehensive understanding that could be defined as a vocation to place. This integration of the symbolic role of place and of the built environment in the natural landscape is represented by art in most cultures.

Seed: Diversification of the use of wattle. Projection into urban space, La Plata, 2001. Photo: Alejandro Meitin

However, for this connection to occur it is not necessary to develop a particular sentimentality or mysticism, or even a vital and intense sense of harmony with nature. It is rather simply necessary to understand and value this sentiment, recognizing that the environment, in its natural and cultural manifestations, is simply an extension of who we are.

Shell oil spill collection of evidence, Magdalena, 1999. Photo: Fernando Masobrio

But in working against this natural understanding, environmental intervention is seen through the lens of an occupation based on the idea of transport corridors, areas divided by economic interests, and a media image produced by vested commercial interests and financial institutions, with only occasional spaces of shining modernity.

Displacement exercise: Santiago Island, 2002. Photo: Thomas Minich

Junco – Emergent Species

During the 1990s, Argentina was immersed in political corruption scandals and in an economic model that kept much of the population in poverty, which subsequently lead to the social explosion that occurred in 2001. The population occupied the city streets merging multiple actions that had been evolving in the peripheries, but that had not yet had global reach. These actions would show the world the crisis of capitalism in Argentina, where the phrase that united a heterogeneous body of people was “Que se vayan todos” (“All of Them Must Go”).1

Founded in 1991, Ala Plástica began working in search of alternative modes of artistic production that could respond to such contemporary social and political turmoil with a particular focus on art and environmental action. In December 1995, the duality of the river-sea, the particular characteristics of the Rio de la Plata coast and the idiosyncrasies of its inhabitants, comprised a potential geography of making that began to take shape, grounded in an experience that connected art to the development of exercises within social and environmental contexts.

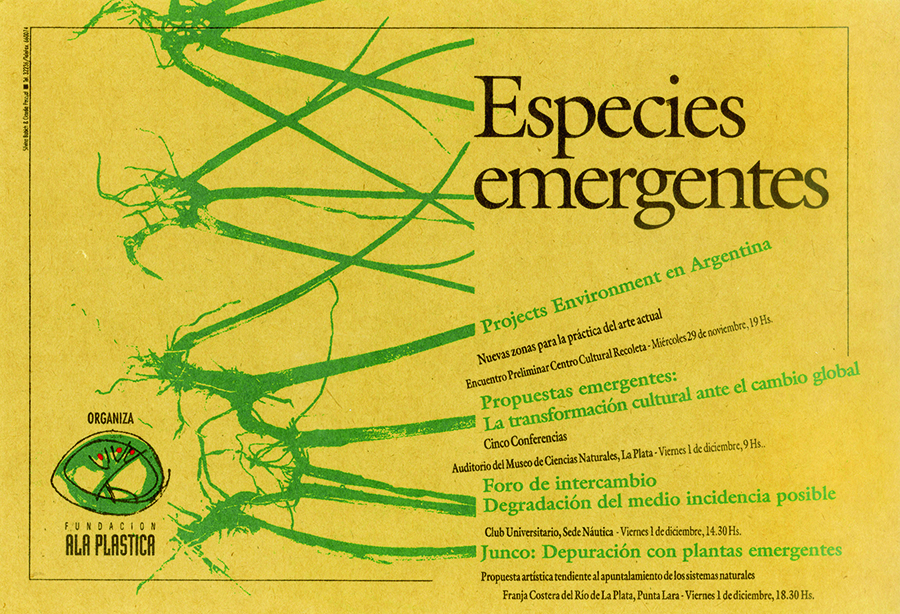

With the advice of the academic Nuncia Tur from the Botany Department of the Museum of Natural Sciences of the National University of La Plata, Ala Plástica began an exercise in environmental restoration together with the region’s inhabitants: producers of junco (native reed species) and artisanal baskets, scientists, naturalists, environmentalists and political representatives. With the goal of sustaining the coastal ecosystem in the region of Punta Lara on the south western fringe of the Rio de la Plata, we started our work on new plantings, techniques of induced growth, and temporary installations made with natural fibers, using a group of semi-aquatic and emerging plants, among them, junco. This was an initiative inspired by an intimate connection with local circumstances: water pollution, destruction of coasts, poverty, riverside culture destroyed by a model of unidirectional development, lack of environmental education, poor infrastructure and flooding. The work also included an inspirational panel presentation where we discussed the threatened coastal natural system and the relationship between humans and nature. Ian Hunter and Celia Larner of Projects Environment, today Littoral Art, UK, also participated as international guests.2 We had met them when we participated in Littoral’s international art symposium, which they organized in 1994 in Manchester, dedicated to the development of “new areas for the practice of art criticism.” There, we were also lucky to meet Suzanne Lacy, Helen and Newton Harrison, Grant Kester, Bruce Barber, members of Platform and WochenKlausur, and many others.3

Planting rhizomes on the costal estuary of Rio de La Plata. Source of the La Guardia stream. Punta Lata, 1995. Photo: Silvina Babich

Junco grows in coastal areas and quickly takes over the soil through underground rhizomes. The reed’s appearance stimulates the creation of new territories for sedimentation, which in turn encourages the entry of other species. After flowing through these areas, water also shows a significant reduction in contaminants of all kinds.

Studying the extraordinary propagation system of the junco, its ability to create new territories and its purifying capacity, led us to the metaphor of rhizomatic expansion and emergence. This idea was central to the initiation of a series of interconnected exercises in the estuary of the Rio de la Plata, oriented to sustain threatened socio-natural systems. Each exercise was linked to the cultural and biophysical ecology of the area, combining an expanded vision of environmental, social and economic complexities and sustained by naturalistic conceptions that activate both individually, as well as collectively, other modes of focusing on the world around us.

Poster: Emergent Species, 1995

Emerging species, including junco and its rhizomatic expansion, interests us as a creative modality and as a means of beginning a process of displacement and communication along the estuary of the Rio de la Plata coast. Our aim is to identify groups of local agents and foster self-managed socio-environmental rescue initiatives that are marked by the metaphor of emergence and the model of rhizomatic expansion. These initiatives will be relative not only to these plants’ behavior, but also to the emerging character of new ideas and practices when faced with the decaying state of relationship networks, as well as to a kind of positioning as a means of survival.

New cultivation techniques, 2006. Photo: Alejandro Meitin

This initiative led to the birth of a desire to rescue remnants of the local culture, using the idea of the rhizome as a conceptual tool that moves by weaving a web of similarities and reciprocities to explore the possibility of development models using integrated creative exercises. In this way, we began the work of connecting threatened natural and cultural remnants by drawing on reflections and perceptions of related problems between urban structures and the natural environment, and we organized meetings in places of environmental stress such as in poor schools, cultivation areas along the river’s coast, precarious settlements, Aboriginal communities, cooperatives, and sectors of the arts and the environment.

Young planters: new forms of working with wattle, 2006. Photo: Alejandro Meitin

The proposal to work together was based on strengthening capacities to move toward new and creative ways to publicly and actively interpret, develop and implement alternative social and environmental profiles. This project was grounded in the systematic compilation of sustainable territorial information (micro-experiences, life stories, productive activities, functioning projects, flows of ideas and artistic creation) with the aim of building a new generative context of ideas and interpretations.

Rio de La Plata Satelite view. Landsat 7

This is the work that we continue to this day – a practice that has generated a nearly indescribable texture of intercommunication, resulting in an innumerable amount of actions that develop and grow through reciprocity. Our process involves addressing social and environmental issues, exploring non-institutional and inter-cultural models in the social sphere, interacting and exchanging experiences and knowledge with cultivators and producers of culture, art and crafts, and ideas and objects.

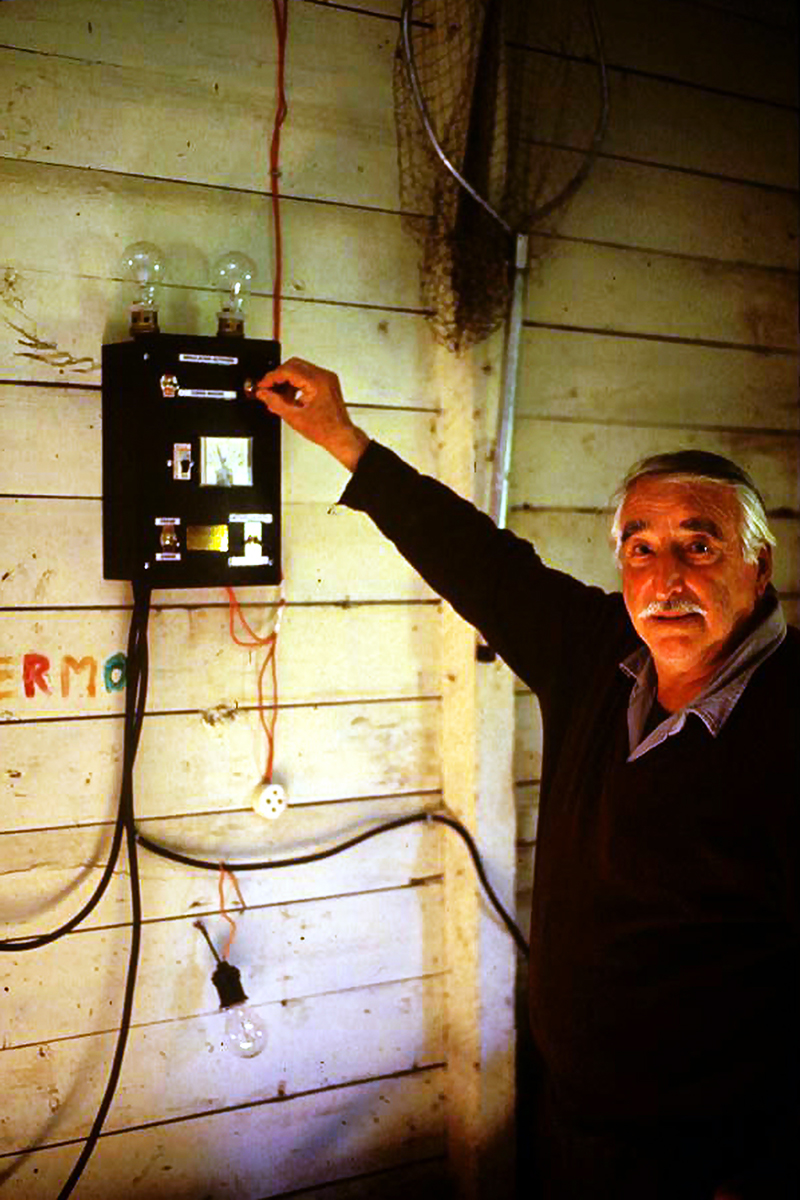

Solar panel project for Paulino Island, 1999. Photo: Alejandro Meitin

Our practice’s challenge is focused on articulating collective forces to catalyze the regenerative possibilities of community-building; here, art is a form of knowledge that enables us to examine urban change and ecosystems and to question what humankind is capable of building or destroying and why we do what we do. Through dialogue, photographic narratives, maps, satellite images, drawings, text and maps that include the insights of residents in the face of actions that harm the environment or the social fabric, we mobilize new procedures for collective action and creativity, generating direct interventions as well as participation in research, exhibitions, residencies, and both national and international collaborations.

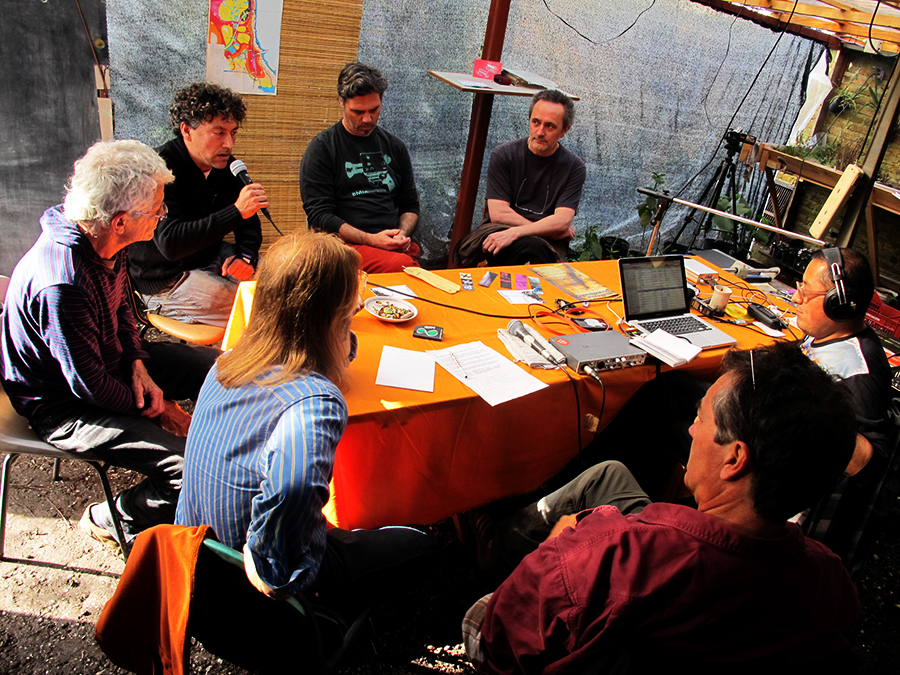

Territory and radicality: Round table with local activists, 2013. Photo: Alejandro Meitin

This learning process has enabled us to recognize certain basic elements that are core to social and environmental regeneration, such as communication and the recovery of the power of making; here, amidst multiple levels of meaning, we find the key value of the experience in how it translates into people’s lives in concrete ways and finds itself becoming something real and useful – a solar panel, a nursery, a communication module, a classroom, or a shed – often focusing on changing the course of events, but which fundamentally provides access to more sensitive visions of our own situation as we live it.

This type of approach has awakened broad interest, enabled the propagation of the reference terms of our work and given support to organizational self-management via drawing on the loose associative forms and mutual empathy in the area of the Plata Basin where we currently develop our activity integrated with multiple networks.

Transformation. Composite image. Photos: Alejandro Meitin

It is not just a simple change of scale or perspective; it is the possibility of developing a new objectivity. Here, the way of seeing a vocation to place is strengthened to incorporate an emerging movement as an area of autonomy in which the anti-power of cultural and natural remnants grows and gains corporeality based on cooperation, the flow of life, in consideration of a movement that unfolds as a social fact. The artwork installed in this event emerges in the experience of collective life and creates the world.

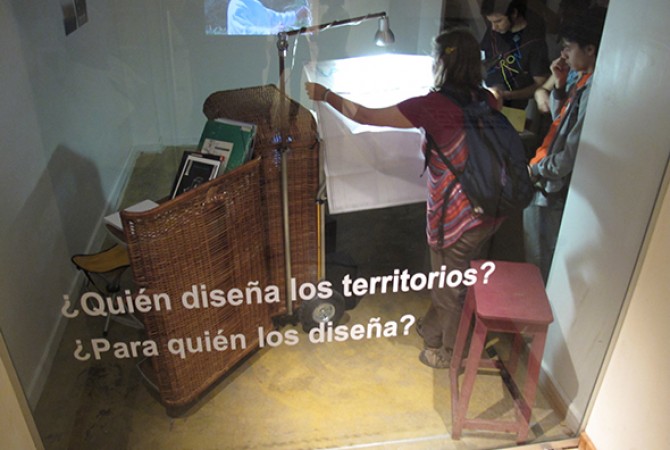

Who designs territories? For whom? Cartography workshop in the Spanish Cultural Center, Rosário, 2012. Photo: Alejandro Meitin

_

1 What was unique about the Argentine rebellion of 2001-2002, which forced the resignation of four presidents in less than three weeks, was the fact that it was not directed at any one political party, but instead against corruption in general. Its focus was the predominant economic model: it was the first revolt of a nation against unbridled capitalism in recent time. See “All Of Them Must Go”. Naomi Klein, The Nation, February, 2009: http://www.naomiklein.org/articles/2009/02/all-them-must-go (Accessed August 2014)

2 http://www.littoral.org.uk/littoralteam.html

3 www.suzannelacy.com; http://theharrisonstudio.net/; http://visarts.ucsd.edu/faculty/grant-kester; http://www.brucebarber.ca/; http://www.platform.org.au/; http://www.wochenklausur.at/

4 The Rio de la Plata basin is 3.200.000 km², approximately one third of the total area of the United States and almost the same total area of all the countries that comprise the European Union. Its waters cross the territories of Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay.