Pay Attention to your Networks/Nets

Gabi Bandeira

Being an artist in a world amidst various collapses, especially those of the environment, requires me to rethink my place in the world and how this reality influences my ethical and aesthetic contribution.

This begins by checking in with the locale from where I speak. I am the daughter of a fisherman, born and raised in an urban fishing region in São Gonçalo, a municipality on the banks of Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro, one that is suffering due to the impact of industrialization.

As an agent of the sensible, a key question for me is: How to fabricate ideas that make us act?

To explore this I will share here the development process of the short film Entornos: Vozes de Gradim (Surroundings: Voices of Gradim), a project that changed my whole outlook fostering possibilities to imagine new futures and horizons of experimentation, ones grounded in collective agency and a continued praxis (especially since I live in the place in which I propose to intervene).

[…] practice means that we consider reality, thought, knowledge (and also action) while they are still taking place.

David Lapoujade1

Reflections: The Street

Saturday, April 11, 2015

São Gonçalo, reflections between the self and the other …

I was studying for an undergraduate arts degree at the University Federal Fluminense. Together with colleagues from the course “Film Documentary Workshop I” we decided to make a short film that we would later title Entornos: Vozes de Gradim. The film would be about the life and subsistence of artisanal fishermen in Guanabara Bay, men suffering amidst a strangulation of their profession due to heavy pollution and the threat of industrialization from large oil companies and clandestine shipyards.

The focus of our attention would be what is known as Colônia [Colony] Zone 8 – there are 32 such zones around Guanabara Bay2 – located in the Gradim neighborhood, in the municipality of São Gonçalo. Colônia is where I was raised and where my father, also an artisanal fisherman, works.

The meeting was scheduled to happen at dawn, at 5 am in the morning. With lots of help, we managed to assemble the equipment we needed and organize vehicles to transport us to the Porto do Gradim pier, in the middle of Favela do Gato [Favela of the Cat] a community in the surrounding area.

We drove down the BR 101 highway, crossed under an overpass, and soon turned right on a dirt road. It was red clay and the smell of wet earth that early in the morning was strong as it had rained the night before, but the sky was beginning to clear and the weather forecasts were saying that it would be sunny.

We got out of the cars and met with the head of the artisanal fishermen association, Paulo “da Balança” [weighing scales guy] together with my father Jorge “Pirulito” [lollipop]. Experienced guides, they soon began presenting the place, a world that is sacred to them, giving us permission to access their sacred everyday. Where the men of the sea moor their CAÍCOS [traditional small fishing boats].

CAÍCOS a makeshift wooden lifeline that both moves out into the immensity of the water and crosses the sludgy silt. Its structure cuts through fluid and locates the north. At times home to fishing baskets and traps, at others the engines that generate energy for many other invisible lives.

We split up…

My body is overcome by an avalanche of senses, lines and shapes, smells and gestures… until the sound of the cars on BR 101 highway let me know that this was not a world we knew, but rather a cavity in space, a place where time seemed to run more slowly and anachronistically. The desire for control was latent, but at that moment I knew that my attention must also be a process.3 For when you control, there is no listening. Attention would be refreshed with each connection.

Body and mind still trying to land in this place. Go back…

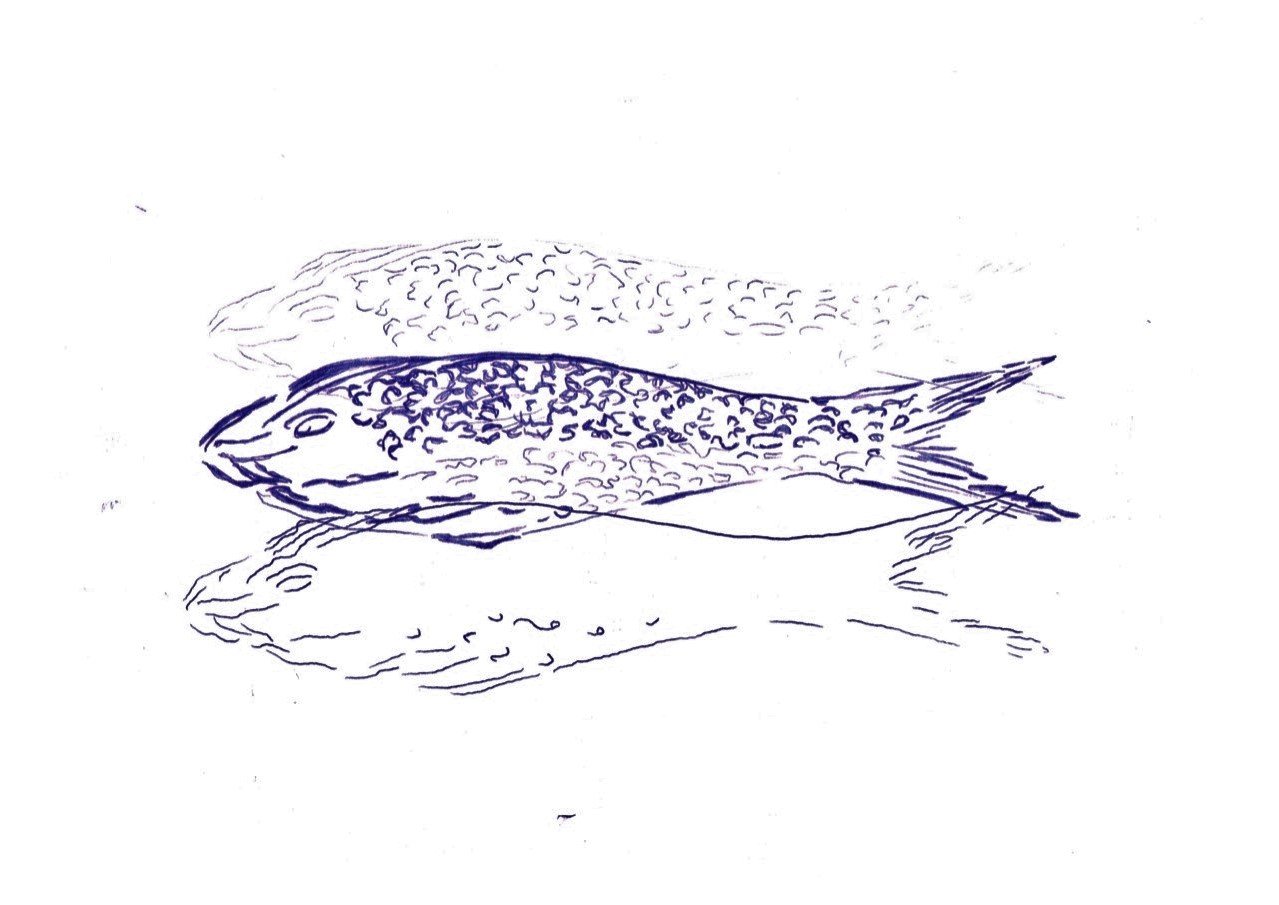

A local fish market operated on the pier, boxes and boxes were being removed from the caícos, filled with various types of fish, bringing the surprise of a Bay unknown to many, a place that still generates life and exudes fertility. We followed the whole process and tried to capture it all in a broad sense, the information that we did not see, but rather felt, distrusting our eyes to try and see with the body. That world was one of constant movement, bonding, and dislocation; in a laboratory of making we invented an experimental and experiential process.

As we shot our decisions also turned the heads of others, glances of which the cameras were the protagonists, yet in our capturing we were also feeling our movements, we were being changed by that experience to the same extent that it interrupted the flow of the place and was generating these changes. This began with a few questions: “Did you take a picture of me?”, “Why me?”, “Is this a college project?, “Where are you from?”, “Can I see your photo?”. Here, the beginning of a bond and a propitious environment for conversations was created. This also made us ask ourselves: “What is the meaning of social bonds?” and “Who were we as researchers?” Together we comprised many vectors, a collective agency.

Fish… Mullets are good grilled for a barbecue, as they are very “rancid”, as the locals say, it was not suitable for frying. Carapicus [carapau – horse mackerel], swordfish, snapper, anchovies, sea bass, hake, pomfret, dogfish, catfish, some only common to the region such as chereretes, cocorocas, mama Reis, croaker, palombetas, and trilhas, among so many other varieties of fish could be baked, fried, cooked or grilled. At that moment, we started to hear the stories about the fisheries and the recipes for the fish, in an outdoor cooking school, where we could see the difference between scales, sizes and colors, the tastes and the dishes were imaginary, but were materialized by and made present with the richness of details contained in the voices of fishermen.

In addition, we observed the various existences that coexisted in that place from the middlemen (professional buyers and traders) and machinists (equipped with a type of cart to remove fish from boats, to be weighed) to the fish cleaners, fishermen, and the head of the association, who was responsible for weighing the boxes and organizing the day’s prices and local buyers.

So, there we were all together at dawn in this small effervescent space, below BR 101, a place called by many “the arm of the sea”, a place without much current, at low tide. The bottom was visible at some points, in a mixture of several layers of oil and mud, that day something was trying to get rid of this background of silt, perhaps our minds, in a desire to understand the stories of that environment and how those stories related to the social and environmental problems we were observing.

Writing Crisscrosses

Some time in the present, 2020

Write through; write what crisscrosses. The desire to see traces and lines as possibilities to rethink my way of being and learning. Re-signify the word. And the world, made up of not only meanings, but also signifiers.

The weave of lines that dare to jump out from the scenes contained in these memories, gives strength to the form born out of this entanglement.

Reflections: Residence

Wednesday, July 1st, 2015

We stopped the car at the end of Paranavaí Street, located in the Boa Vista neighborhood. From there we saw the caícos moored in a possible tributary of the Imboaçu River (with its source in the district of Sete Pontes, it passes through several neighborhoods, draining a part of the Neves and Centro neighborhoods). We found out later, from one of the residents that the name of the street we were on meant: “cove of the great river”.

Welcomed with freshly brewed coffee, we organized the equipment, tested the light, the microphone, and began to chat. For this meeting, the conversation had been somewhat pre-planned as we knew we would interview the artisanal fishermen Antônio Carlos de Brito Maria (Bicudo “pointed”) and Mauro César Nascimento da Silva (Pezão “big foot”), both professionals with more than 30 years of experience.

The initial questions were about the relationship they established between the proximity of the port and their homes, its importance and what were the difficulties they faced in the silting of the streams and rivers in the region. They replied that they used the streams to reach the sea, so the relevance of living close to them and being able to have the safety of docking their boats close to their homes, meant that they could easily go out to work, like someone who takes the bus in the big cities. Another aspect addressed was their in-depth knowledge of the region, for example they know where there is “draft” (depth for navigation) or where the streams had disappeared, due to being dried out or pollution. These men not only hold compasses to the sea, but also, to the land.

At that moment, memories got lost in the midst of the stories they remembered, of the difficulties they increasingly faced in using this natural system created by the rivers. Over the years, they had to adapt to the new flows imposed by unbridled urbanization and negligence of public authorities that do not invest in an effective basic sanitation program. It is not by chance that in São Gonçalo more than 81.4% of households do not have access to the general sewage network, with the result that raw waste is dumped into the streams.4

We saw proof of all the reports, as they were being told to us: “Look here! Right now you will see what comes out of that pipe over there goes straight into the river.” As we were on the bank of the stream, we could see the result of when toilets were flushed in the houses. They added: “This makes our work increasingly difficult, we live in an unhealthy environment. Our boats and nets are damaged by sewage and materials discarded illegally in the rivers that end up becoming garbage dumps. We even found a syringe here! Look at our fishing net.” And they started to mend, the cloths in front of us …

REDE [meaning both network and net], hunting device composed of three types of nylon, it is the sieve where the water escapes to leave only the catch.

Equipped with the AGULHA [needle]…

AGULHA extracted from the trunk of an orange tree and transformed into a weaving stick that stitches and restitches, ties and unties the knot. Guided by the language of the hands, their [native] tongue in the form of movements and gestures, that braid and join the threads of the net, ropes, lead, and buoys. After all, to resist the immensity of the sea it is necessary to have a fraction of lightness, that can be submerged in order to breathe.

At the same time that they denounced this neglect, they praised the practices that have been passed on from father to son, they told us how they learned to mend nets and at what age. They remembered when they were children and used nature both as a yard to play in and to follow the footsteps of their ancestors. At this moment, the question arose as to whether they wished their children and grandchildren to have the same job, they replied that no: “The sea life is very harsh, in the sardine season we work throughout the night till dawn, we have to SAFAR [pick through] each one, to in the end see that the price of the fish is only worth a few cents.”

SAFAR, choreography that unravels, freeing those small mouths caught in the mesh of the trap. Driven by the hands that become machines and fight with time. One by one by one. Sardines and Barracudas.

We understood this experience as a moment of welcome, hearing the words and reports of these men, letting them speak, so that afterwards we might offer up our thoughts. Caught by surprise at various moments, this dynamic enabled us to delay the impulse to take control. In addition, we realized the importance of “speaking from within”; giving visibility to these men also emphasized the magnitude of the Caiçaras communities. The traditional inhabitants of the Brazilian coast are called caiçaras, arising from miscegenation between Indians, whites and blacks whose culture comprises artisanal fishing, agriculture, hunting, vegetal extraction, handicrafts and, more recently, ecotourism as practices of sub-existence.5 As holders of genuine knowledge and as agents in favor of an interconnected, cosmic and systemic environment, they not only know their seas and lands, but also understand the forces that govern degradation.

Fishing for Memories

Some Time in the Present, 2020

Being in a known territory is both an advantage and disadvantage. A certain ambivalence of being an insider with my local viewpoint had to be turned off to allow for the possibility of knowledge yet to be discovered. The “bait” that connects me to experiences yet to be lived, found in the possibility of sharing universes. Universes embedded in the landscape, hold the power to drown us.

Reflections: The Ranch

Wednesday, July 1st, 2015

After the meeting at Paranavaí Street, we cut through the Boa Vista neighborhood until we reached Rua Professora Maria Joaquina. Now we were at Praia das Pedrinhas (Beach of Little Stones), a place where the region is once again divided by the BR 101, where we met with the artisanal fisherman, Jefferson Figueiredo da Silva (Jeffinho), who has also worked in the profession for over 20 years, mostly seasonally along with other types of work related to life at sea, in shipyards, on trawlers (fishing vessels larger than caícos so they are not considered as artisanal fishing) and deep sea fishing (outside Guanabara Bay).

We shoot the interview in the place commonly called by fishermen RANCHO [ranch].

RANCHO is where the land is reinvented, where ways of coexisting together are rediscovered. A place where the possessive pronoun is almost extinct, what is mine is yours, is ours. A storehouse for boat parts, oars, nets, and engines and a site where plans and actions are drawn up, but also, it is an infirmary, where bodies and hulls of boats are regenerated.

Go back…

This land shared by some of the fishermen in the region is very familiar to me. It belongs to my father, Jorge da Cunha Pinheiro (Pirulito), today one of the oldest proprietors of the rights to the beach, also joined us for the interview. In that place of unpaved earth, facing the sea and side-by-side with the MANGUE [mangrove], the limit between the sweet and salty, between the earth and the fluid ground.

MANGUE Where the anatomy of aerial bodies rules over developed beings, where one always walks sideways in small steps in order to understand the shifting perimeter. These are the constitutive choreographies of the place. Where there are holes in the earth, made by “claw” workers, holes that are also mouths, exhaling salty breath.

Go back…

Everything was noisy, the songs of the crickets and frogs, the engines of the boats, the sound from the bars, dogs and cats, the sound of the mangrove and sand being blown by the wind. We turned on the cameras, another sound.

We began asking Jefferson questions about how he got into fishing and he replied that his father was a crab fisherman, who sold crabmeat already “shredded”, to help to add to the family income, but that he also fished with rods and hooks as a pastime. So he ended up teaching his children. Jefferson started working with my father when he was around twenty years old, connecting the two men. Both are present for our filming.

My father: “Do you remember that Jeffinho?”… “I remember Pirulito, it’s from one of the oil disasters in Bay, in the early 2000s?” From here the conversation continued…

They started to remember disasters, that now in 2020 are over 20 years ago. Jefferson remembers and explains in detail the stages of the disaster, as it occurred and the impunity [of it all], because today even he and many others have not received compensation for losses and damages, nothing has been the same since, in his voice we heard the pain of knowing that fish species upon fish species were extinguished, the Bay already suffering now entered into collapse. Collapse…

He remembers the chemical material used to cover up and decant the oil to the bottom of the sea at the time of the disaster, showing an apparent improvement in Guanabara Bay, but that still today, after a rain, or with the passing of a net drawing on the bottom, the soil is then mixed and churned up, bringing the viscous and sticky oil to the surface. Oil that suffocates, kills slowly, and silts up.

He and my father tell us about objects such as POITA [small anchor]…

POITA grabs, holds and does not let go… It is fixed to the ground when the tide is low, when the firm in the fluid can be found. A portable port. The point amidst continuous and infinite lines.

But also like REMO [oar]…

REMO the union between body and object that creates leverage, moves through the immense and gains propulsion. Moving, not being static in the immensity.

Go back…

They reflect on how these materials still get stuck in the silt and how these muddy waters haunt their future and (r) existences.

In this context, “word-concepts” institute themselves as if layers in the landscape, conditioning the exercising of a “compost viewpoint” that also uses other senses, such as smell, hearing, and touch, in order to see. Freeing up the poetic amidst this evidently hard daily life. These word-concepts reveal the pluralism of my artistic making, when the word is no longer enough, it is necessary to unite it with a drawing that is also text.

In this way the “clinic of doing” [of filmmaking] showed and unveiled the performative character of this experience,6 one that demanded attention to listening, to the movement of feeling the body in the environment, that is, observing how that body reacted to that same space, welcoming the words of the fishermen, their emotions and discontent.

In addition, it was possible to understand ourselves as witnesses to that reality that had imposed itself, bringing with it the responsibility of how we would tell that story, how we would share and transforming it into a sensitive form, expressing and trying to expose and build on tensions, in order to awaken new perspectives and who knows perhaps actions.

One thing I would like to point out is how “pure experience” (a first, generative of a flow of conscience) had as its embryo the classroom, evidencing the importance of public universities as triggers of creative overflow.

In addition, it is also worth highlighting a pedagogical thinking that welcomes the students’ stories and experiences. This contributes to a decolonial perspective, one that subverts the place of the teacher and the student, blurring traditionally imposed limits, and enriching debate in the classroom, a movement that aims to bring the university and the external world closer, as well as making the same students look to themselves before thinking of a reference that already exists in the world.

In this way they can be doers and writers of their own worlds, paths, and futures.

Some Time in the Present, 2020

Practical consequences…

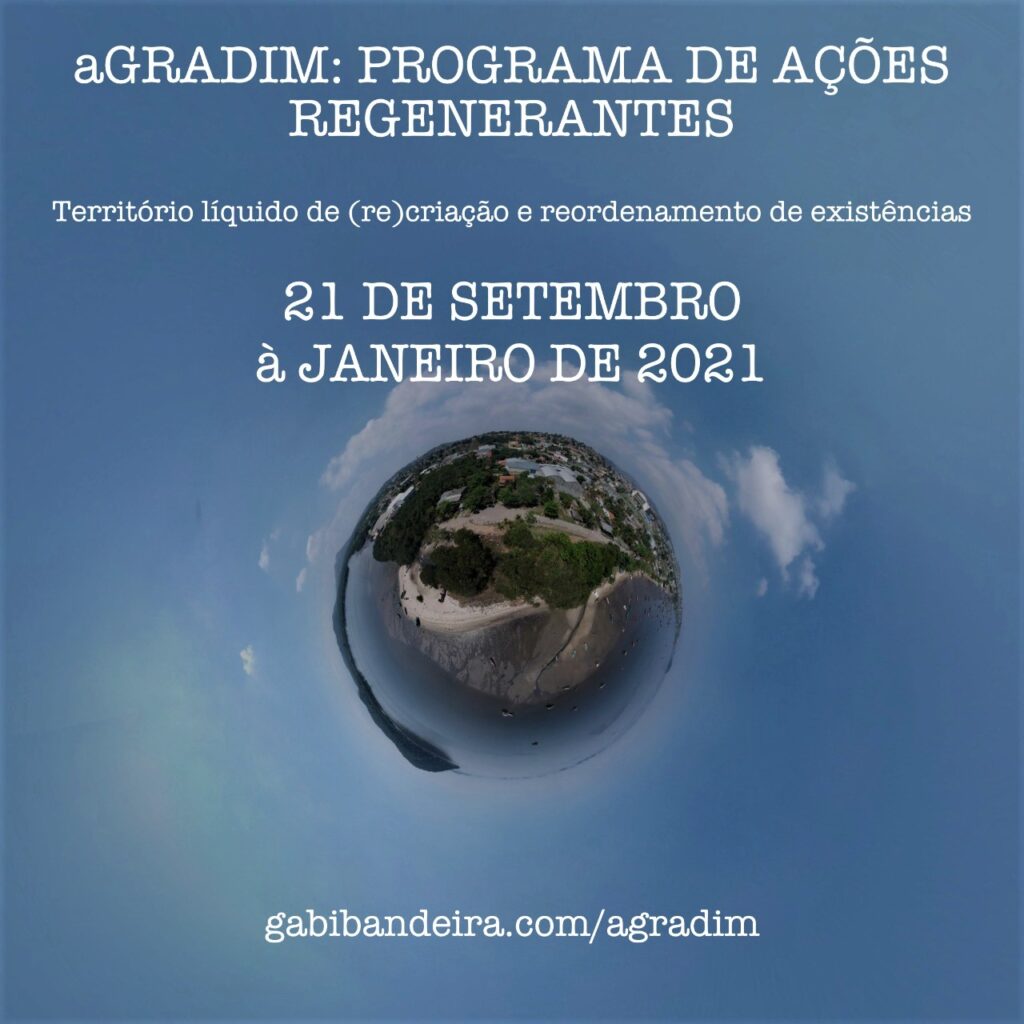

Inspired by this film project five years ago in 2020 I find myself proposing another socio-artistic agency, in Cais do Gradim and its surroundings, such as Praia das Pedrinhas and other Caiçara regions in the municipality of São Gonçalo.

Honoring and drawing on the work developed with the short, especially to make present the sense of an unfolding between both actions, I named the work “aGradim” – a play on words meaning both a small pleasure (gift) [“agrado” in Portuguese] and the name of the place –, in which I invite six artists to participate in a program of actions to be carried out by each one in this territory.

The entire process for making action proposals is grounded in a territorial investigation, that is, artists are invited to get to know the places, realities, and existences that experience this space, such as fishermen and artisans (net makers, locksmiths, carpenters, skilled laborers). [It is a process that] respects the need to give visibility to the Caiçara community in the region, to be attentive to their struggles and demands, always with a sensible eye as a tool.

Soon, these experiences will be translated by the artists into new actions to be offered to the community of these regions, in an act of thinking about the social making of art.

But now, in addition to facing the environmental collapse, there is a collapse in health system, with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, bringing the challenge of re-signifying a relational aesthetic based on physical presence and contact.

Important to note that, at first, I could not see any future forms for how this process might take place, but, after much listening, in a work of virtual interviews with the community and with the artists themselves during the initial moment of the pandemic (between the months of April and June 2020), I understood the need to “cling to life”, to get a handle on what makes us pulsate, our artistic making, in order get our breath back.

I started to hold meetings between the community, researchers, and local agents in this Caiçara region and the artists in order to better “listen” to the place, and to prepare us for the physical activities that will occur in the beginning of 2021.

Through these experiences and developments, it becomes more and more evident that social agency is a convention inherent to my work, connecting with the form of my being, with communication (orality), the possibility of sharing, planning (creating) and developing together, reflecting collectively on the “how” and the means of manifesting the sensible. Equally significant is the importance that this agency embraces continued actions, not only to enable an understanding of the changes that may or may not result from the actions proposed and realized, but also to underline our responsibility to these territories, even when we leave them.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the interviewees, Antônio Carlos de Brito Maria (Bicudo), Mauro César Nascimento da Silva (Bigfoot), Jefferson Figueiredo da Silva (Jeffinho), Jorge da Cunha Pinheiro (Lollipop) and Paulo Fernandes Caldas da Silva (Paulo da Balança, former president from the fishing colony of Gradim, now deceased). To the professors, Miguel Freire (Dept. of the UFF Media Study Course) and Luiz Guilherme Vergara (Dept. of the UFF Arts Course). To the residents of Praia das Pedrinhas, to the farmers and artisans, to the residents of the Cicero Gueiroz colony, in Gradim, all in São Gonçalo. To my classmates and classmates, Felipe Dal Belo, Marina Silva and Rodrigo Freitas, who helped build this narrative told through the short / documentary, Entornos: Vozes de Gradim, produced between 2015 and 2016. To my family and friends.

***

Gabi Bandeira

Artist proposer of collective agency and a researcher. She is currently studying for her masters’ degree in Contemporary Studies of the Arts at Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF). Through the socio-artistic agencies she proposes, her research investigates conventions created through a state of invention.

1 David Lapoujade, William James, a construção da experiência.(São Paulo: n 1 Edições, 2017) p 11

2 The Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade [Chico Mendes Biodiversity Conservation Institute] is an alternative autonmous organization linked to the the Environmental Ministry and part of the National Environmental System called Sistema Nacional do Meio Ambiente – Sisnama). https://www.icmbio.gov.br

3 Drawing on cognitive studies and research, attention with fieldwork, is understood as part of a perspective that there is no data collection, but rather from the outset, a production of research data. See: Virgínia Kastrup, Eduardo Passos, and Liliana da Escóssia, “Pista – O funcionamento da atenção no trabalho do cartógrafo”in Virgínia Kastrup, Eduardo Passos, and Liliana da Escóssia eds., Pistas do método da cartografia: pesquisa – intervenção e produção de subjetividade. (Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2015) pp. 32-51.

4 https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/rj/sao-goncalo/panorama

5 Cristina Adams, As populações caiçaras e o mito do bom selvagem, Revista de Antropologia, São Paulo, USP, 2000, V. 43 nº1 p. 146 and Antonio Carlos S. Diegues, Diversidade biológica e culturas tradicionais litorâneas: o caso das comunidades caiçaras, São Paulo, NUPAUB-USP, 1988. Série Documentos e Relatórios de Pesquisa, n. 5. p. 9.

6 Silvia Helena Tesedso, Christian Sade, Luciana Vieira Caliman, “Pista da entrevista, a entrevista na pesquisa cartográfica: A experiência do dize” in: Pistas do método da cartografia pp. 92-127.