Unveiling the Hidden: Socially Engaged Art Practice in Ireland

Helen O’Donoghue

This essay explores the work of three artists directly engaged in socially critical histories and the contemporary realities of Irish life, as well as briefly contextualizing the evolution of what has been termed socially engaged art practice in Ireland. Each artist grapples with different dimensions of the hidden: Bernie Masterson works with prisoners in the Irish prison service telling their marginalized stories and unveiling histories of institutional abuse; Seamus McGuinness sheds light on painful social stigmas through his collaborations with the families of young suicide victims; and Vukašin Nedeljković documents the experience of recent refugee and asylum seekers in Ireland.

The Artists: Bernie Masterson, Seamus McGuinness, Vukašin Nedeljković

In 2014 Bernie Masterson asked me to come on a studio visit to view her most recent work and to write about it for her forthcoming exhibition at Rua Red, in Tallaght, Dublin. This work was a significant shift in her practice as an artist. On initial viewing of the videos I felt overcome by a chill, a damp cold deep chill; resonating with my own past, our collective past of secrecy, conspiracy, and unspoken truths.

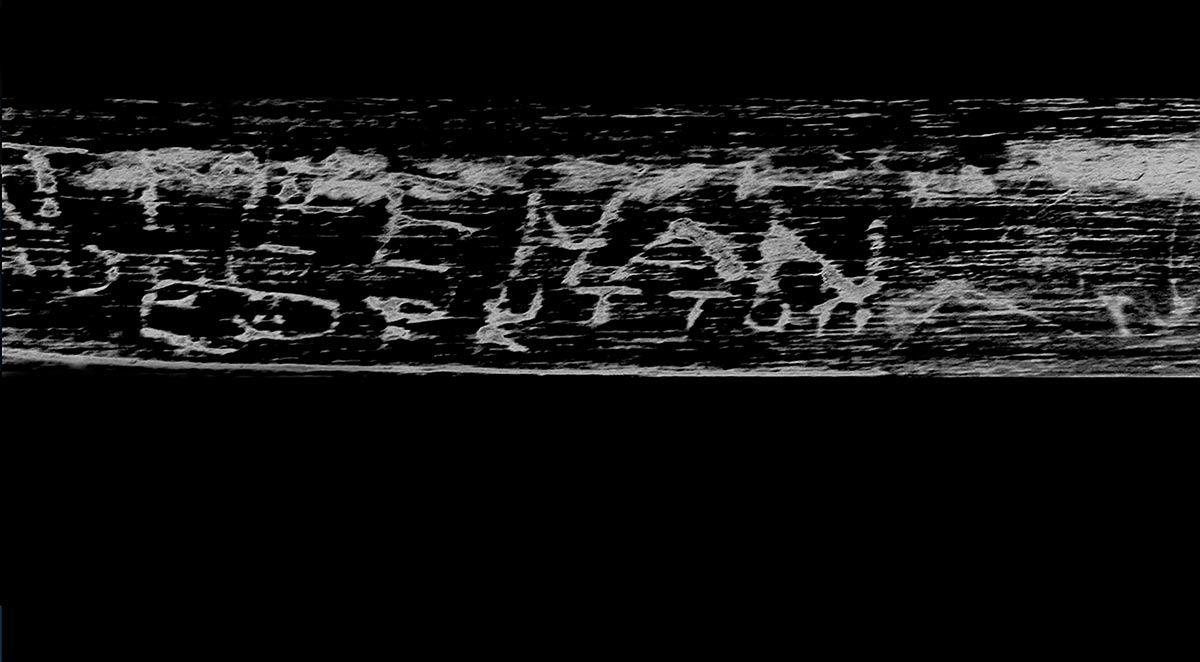

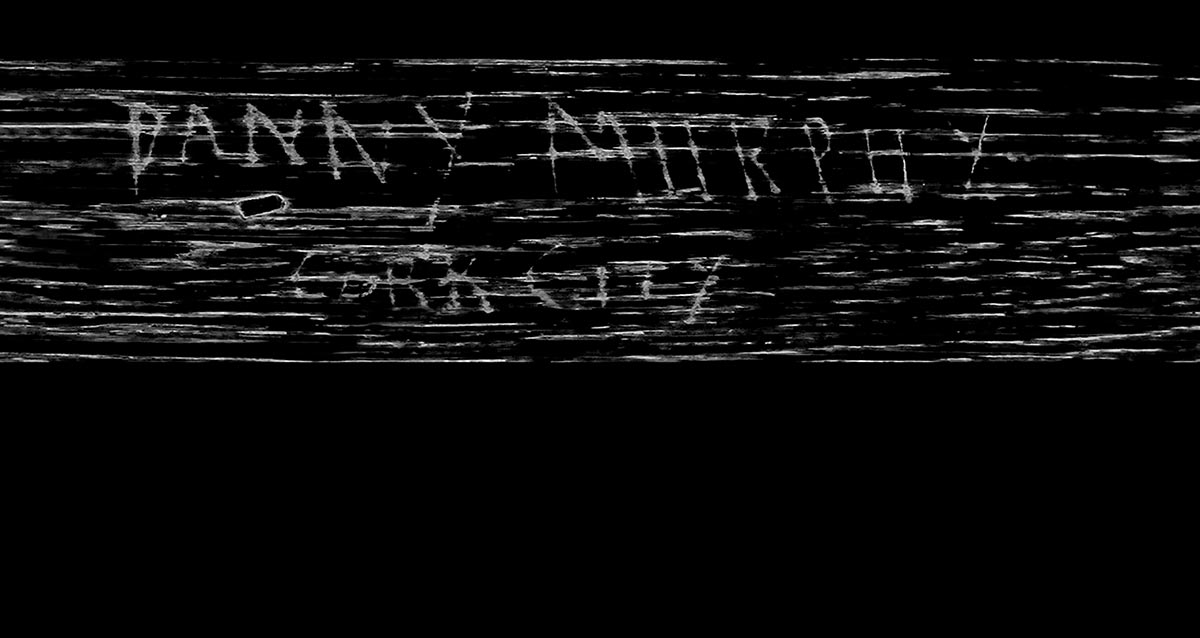

One video piece, Shrine, for example, focuses on the various markings left by children scratched into the surfaces of church pews. These appear abstract initially but soon names can be deciphered, children’s attempts to leave their mark in these places of incarceration. The soundtrack is ominously ambiguous and disturbing. The sounds do not seem to belong to the tones of a musical composition or to be the ambient sounds of mark making, rather they fight in a duel of actual and constructed dis-harmonies reflecting the images of letters etched into wood grain that could also be musical notation or old copy books from that time. I think of that great line “[…]when the air inhales you” by Máighréad Medbh, a poet that Masterson has subsequently collaborated with.1

Masterson’s imagination has long been occupied with reconstructing what she has seen and heard. Since 2014 she has continued to explore prisoners’ experience and personal stories in a sequence of video works that are illustrated as part of our conversation elsewhere in this publication. This body of work presents a coherent narrative, one that moves us from a horror that speaks to the dispossessed in all of us through a process of assimilation of these experiences to present us with the possibility of transcendence.

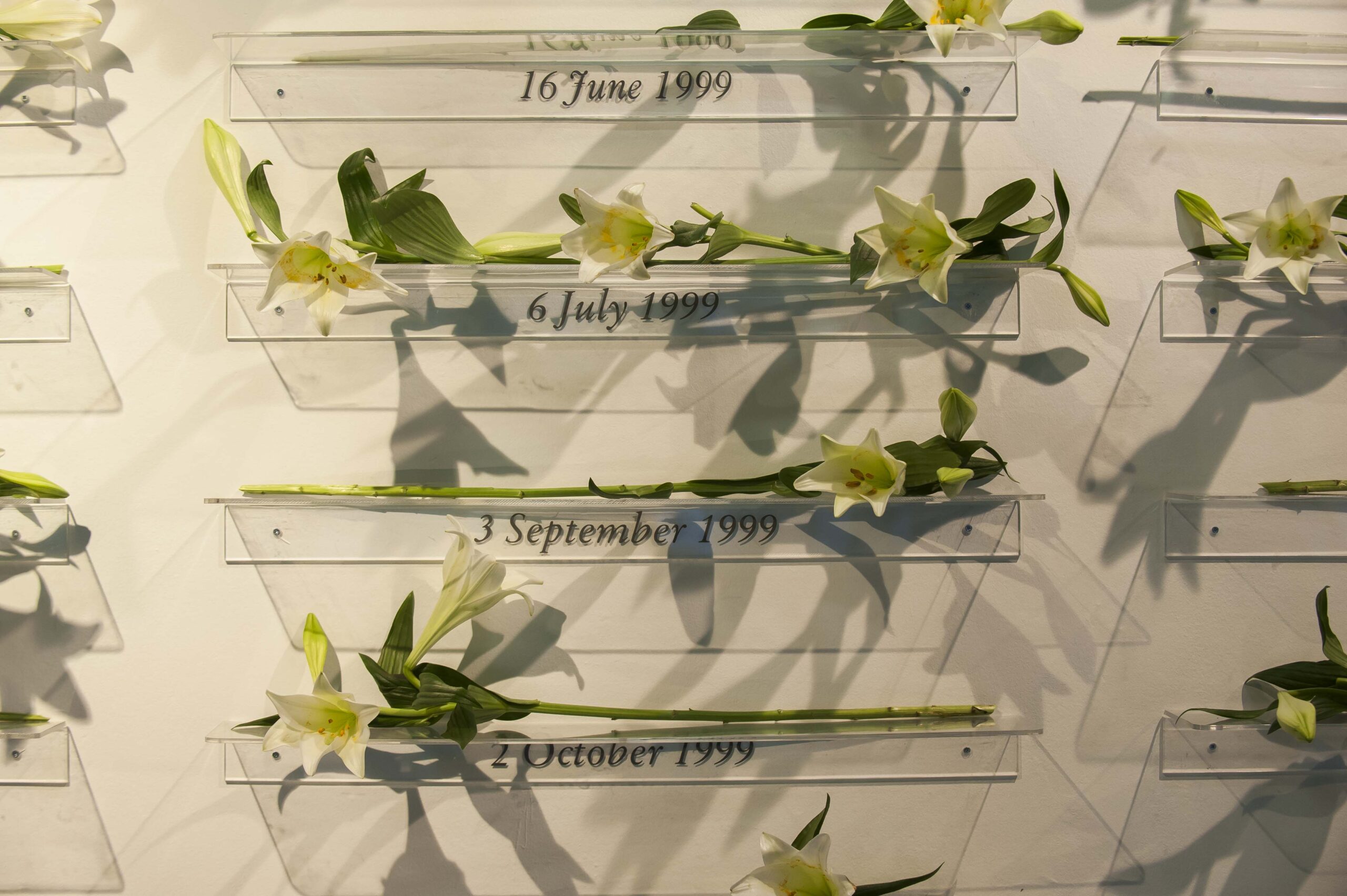

In Seamus McGuinness’ installation 21g, 2003, numerous shirt collars form the elements of this evocative artwork. The allure of the textiles floating in the space of the gallery is reminiscent of a murmuration. Shirt collars torn away from the body of the shirt, with strands of untied threads trailing to the floor; floating almost like ethereal beings separate from the ground, at neck height; white collars casting shadows that attract the viewer’s attention and then, shockingly remind us of what has been torn away from their families – their loved ones taken by the absolute act of suicide. Like Masterson’s work there is an aesthetic that references the ritualistic and the ethereal, recalling the theatrical aesthetic of the Catholic church, enveloping the viewer in its mysteries, and not revealing but concealing (maybe consciously hiding or protecting the truth). This seminal work sits alongside memorabilia that Seamus has been given by hundreds of families who have lost their children to suicide. The use of cloth remnants recalls the ancient Irish tradition of the Rag Tree whereby rags are placed on trees by people who believe that if a piece of clothing from someone who is ill, or has a problem of any kind, is hung from the tree the problem or illness will disappear as the rag rots away. Over the years, McGuinness has accumulated an ongoing audiovisual archive of the many encounters that he has created to bring families together to mourn, recall, and share in their common traumatic experience. Each encounter that I have had with McGuinness ’ working process is a moving experience of a dialogical interpersonal relational encounter where the artist’s empathetic nature holds the grieving families in his care. The work thereby acts as a catalyst for communion between people both verbally and non-verbally. Sometimes silence speaks louder than actual words or utterances.

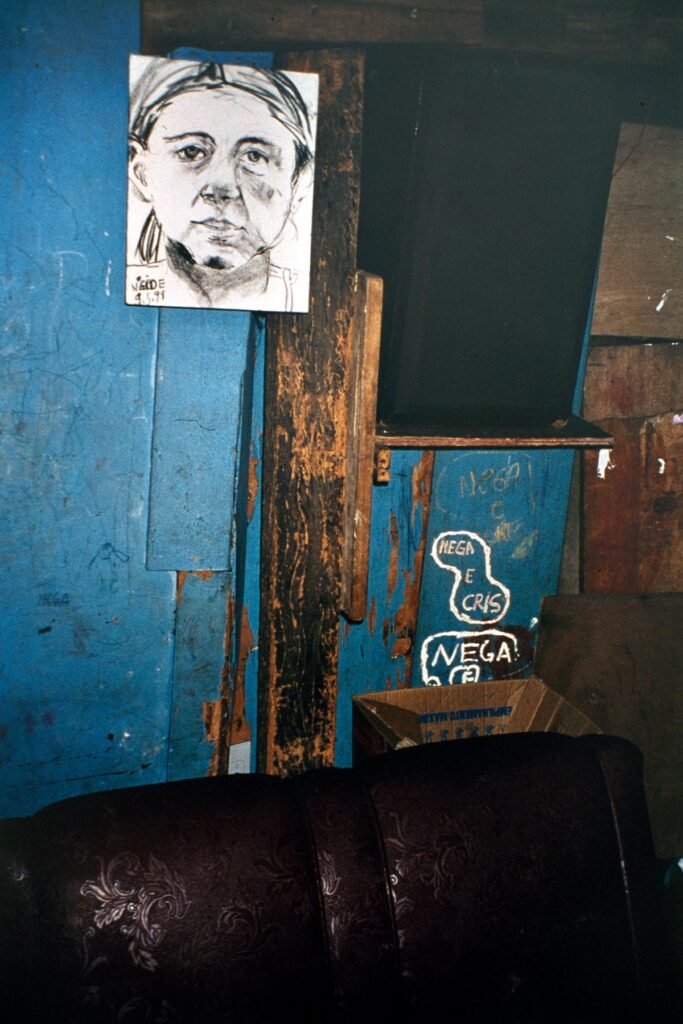

Vukašin Nedeljković is one of a new generation of artists who are emerging in Ireland who have had first-hand experience of the Irish State’s provision for refugees and asylum seekers. He, like others, represent a new contemporary voice which is speaking truth to power. Nedeljković’s photographs employ a photorealism to present the stark reality of the environments that have been assigned to recent asylum seekers to the Irish state. These photographs do not hide what is there. They reveal to the viewer the harsh realities and actual physical environments of the Direct Provision Centers. This scheme was established in 1999 and has included 150 centers some of which are now closed, that were dispersed throughout the country, many in remote places on the edge of cities, on the periphery of Irish society. This reduced the potential for integration with local communities turning the centers into ghettoized environments. The photographs are a poignant and shocking representation of the neglect that the residents living there were forced to endure.2 Nedeljković states on his website that:

The photographs in the archive are devoid of romanticism and aestheticism; they simply document the everyday reality for asylum seekers. This work is political and socially engaged. My work is not so much inspired by contemporary or historical photographers and artists, though I will not deny the influence of the American Documentary Photographers or the German School of Photography, as well as writers like Primo Levi and Franz Fanon, or radical philosophers like Walter Benjamin and Giorgio Agamben.3

Socially Engaged Art Practice in Ireland: Background Context

In spite of the recent opening up of Irish society to embrace more liberal social changes, Ireland in 2020 is still grappling with a very complex postcolonial history. It is less than one hundred years since we became an Independent State and the last century was marked by revolution, independence, civil war, partition, economic underdevelopment, and emigration. The social life of this new independent state was shaped by the close alliance of a conservative political class and an equally conservative doctrinaire Catholic hierarchy. These forces had effects on all aspects of social, educational, and economic life. In spite of the radical changes that the electorate has brought about in recent referenda, (expressed most publicly through recognizing women’s rights to autonomy over their bodies in 2018 and same sex marriage equality in 2015), there is still nevertheless an enduring legacy of the early 20th century’s repressive institutional systems. In today’s Ireland many socially engaged artists grapple with this legacy and its related impact and their work draws attention to previously hidden social issues and voices, bringing them out into the open. Over the past thirty years socially engaged arts practice has grown in its complexity to engage, support, and advocate for change. The three artists that I am focusing on in this text represent this growing practice in Ireland that is gaining force, intellectual rigor, and access both to and within cultural institutions and critical art discourse.

To frame the work of the three artists I will outline in brief the evolving terrain in which Irish artists have been working since the 1970s when community arts – an influential precursor of socially engaged practice – emerged as a grass roots movement.4 As a term community arts is not native to Irish ways of thinking about the arts and society5. In practice it literally implies artists working in community settings outside of traditional art contexts using a diversity of art forms, such as theatre, parades, murals, and festivals6. First appearing in the British context, community arts became key to efforts tied to the post World War II deployment of culture as a tool to promote democracy and the 1960s drive for social change and soon became a political movement marked by a central concern for cultural democracy. In Ireland community arts began to emerge from ground up movements in a context where at the time few cultural institutions and support mechanisms existed. In this cultural context artists in Ireland have worked creatively both outside and inside the studio as teachers, tutors, and facilitators and current multifaceted practices have their roots in the challenges they encountered and the impacts of socio-cultural and political movements of the time period ranging from the late 1960s counter culture and (Hippy) rebellion to the Cuban revolution, the Black Panthers, anti-Vietnam war agitation, and global student protests. In addition to these influences, working class activists in post-industrial Britain, seeing elements of these movements as a predominantly middle-class phenomenon that further marginalized their own interest, in turn led their own revolt. By the late 1970s these critical and social energies expressed themselves as a community arts movement.7

Since the 1970s, the understanding of practice has evolved from community arts to include the evolving terminologies of the participatory, collaborative, and socially engaged. These practices all involve levels of participation and collaboration by both public and artist. The underlying motivation of artists who wish to engage outside of the hierarchical structures of a hegemonic art world led them to adopt strategies that were inclusive of others in their arts practice and to question the notion of the single authorial voice, decisions about who gets to participate in the production and distribution of artwork, and strategies around how this should be done. Influenced by diverse late 20th century postmodern theoretical positions and evolving critical discourses such as feminism, critical pedagogy, and decolonial theory and practice Irish artists have tested the parameters of these practices.

In the early 1990s Ireland saw significant changes in socio-political fields, most notably when in 1991 the first ever woman candidate Mary Robinson, was elected as President of Ireland. As a left-wing politician and human rights lawyer, she brought radical changes to the role and is widely regarded as a transformative figure for Ireland, and for the Irish presidency, revitalizing and liberalizing a previously conservative, low-profile political office. Her period as President coincided with the election of a Coalition government who introduced the first ever Minister for Culture, the poet and human rights activist Michael D Higgins, currently President of Ireland. Irish society began to experience a period of openness and cultural change in this last decade of the twentieth century and a new wave of development in both arts practice and critical reflection emerged. A significant event in this was the opening of the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) in 1991.8

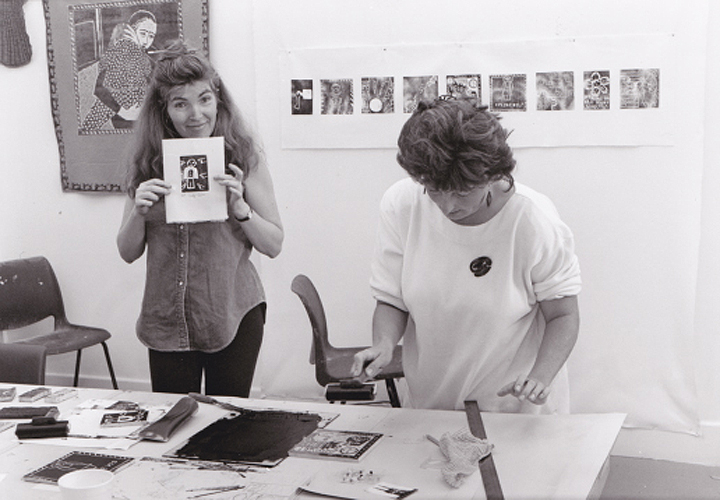

IIMMA’s founding Director, Declan McGonagle’s policy was to open access to the arts for all and to create a space for artists and non-artists to work together. I was appointed as the first Education and Community Curator.

In the first ten years a radical policy of inclusion was embedded in this new institution with artists working directly with communities drawn primarily from the neighborhood surrounding the museum – a largely working class demographic experiencing high unemployment with a high proportion of people living in state provided public housing. This area is in postal code Dublin 8 and lies south of the River Liffey that divides the city’s north and south side. Kilmainham lies in the latter and in the early 1990s was seen as being too far from the city’s cultural centre and therefore locating the country’s first museum dedicated to modern and contemporary art was heavily criticized by many as ill advised. The work that developed brought people that would not have previously engaged with a cultural institution or with contemporary art, together with artists who were testing out models of community engagement and political activism.9 Projects emerged that foregrounded the voice of older people;10 inner city women’s stories; unemployed men; children and teenagers; and explored issues such as personal and community identity; violence against women and the threat to public housing. Using its international exhibition and Artist Residency programs, IMMA facilitated relationships between national and international artists and these communities.

A series of experimental projects were put in place where artists worked in collaboration with a range of communities in the immediate proximity of the museum in Kilmainham11 and later, from 1995 onwards, throughout the country as a whole through the Museum’s National Programme. Arts programming initiatives centering on participation were developed. Their outcomes were exhibited, and findings evaluated and disseminated through publications and public conferences. The exhibition, Unspoken Truths, presented at IMMA in 1992 marked a new highpoint in community arts engagement, since it was located in a national institution, backed up by the supporting frameworks of the museum, and given real recognition when it was formally launched by Mary Robinson, President of Ireland. The exhibition toured widely until 1996.12

New definitions of work practice emerged as artists engaged in international debates. American artist and curator, Mary Jane Jacobs invited Maurice O’Connell (who had worked at IMMA in From Beyond the Pale, (1994/5) and with Wet Paint’s community project for young people) to participate in her exhibition/project/publication initiative Conversations in the Castle devoted to the theme of changing audiences for contemporary as part of the Arts Festival of Atlanta in 1996 held during the Atlanta based Olympics that same year.13 The ideas of Grant Kester, introduced to Irish artists through the 1998 event Littoral held in Dun Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design and Technology (DLIADT) provided a theoretical basis for examination of participatory practice. The DLIADT symposium linked Irish artists to the international network of artists, critics, and educators interested in new approaches to contemporary arts practice, research, and pedagogy.

Influenced by this context over the past few decades, a number of artists have emerged whose practice has had a significant impact in arts and community development. Ailbhe Murphy, who first came to public attention with Unspoken Truths in 1992, in collaboration with the Family Resource Centre, St. Michael’s Estate, Inchicore and the Lourdes Youth & Community Services, Sean McDermott Street, and IMMA has developed a sustained practice informed by Kester’s emphasis on dialogue and time-based practices termed “dialogical aesthetics.”14 The artist/filmmaker Joe Lee whose work is concerned with documenting Dublin citizens’ experience of urban change, worked alongside Murphy, Rhona Henderson (Scottish) and Rochelle Rubenstein (Canadian) in collaboration with a women’s’ group from Inchicore, Dublin for the Once is Too Much exhibition (IMMA, 1997). Lee’s collaborative artwork made with the women’s group entitled Open Season was acquired for IMMA’s Collection, making it the first participatory artwork in a national collection. Dublin based artist Rhona Henderson straddled both practice and theoretical positioning in the context of international trends and worked on many community programs at IMMA and elsewhere.15

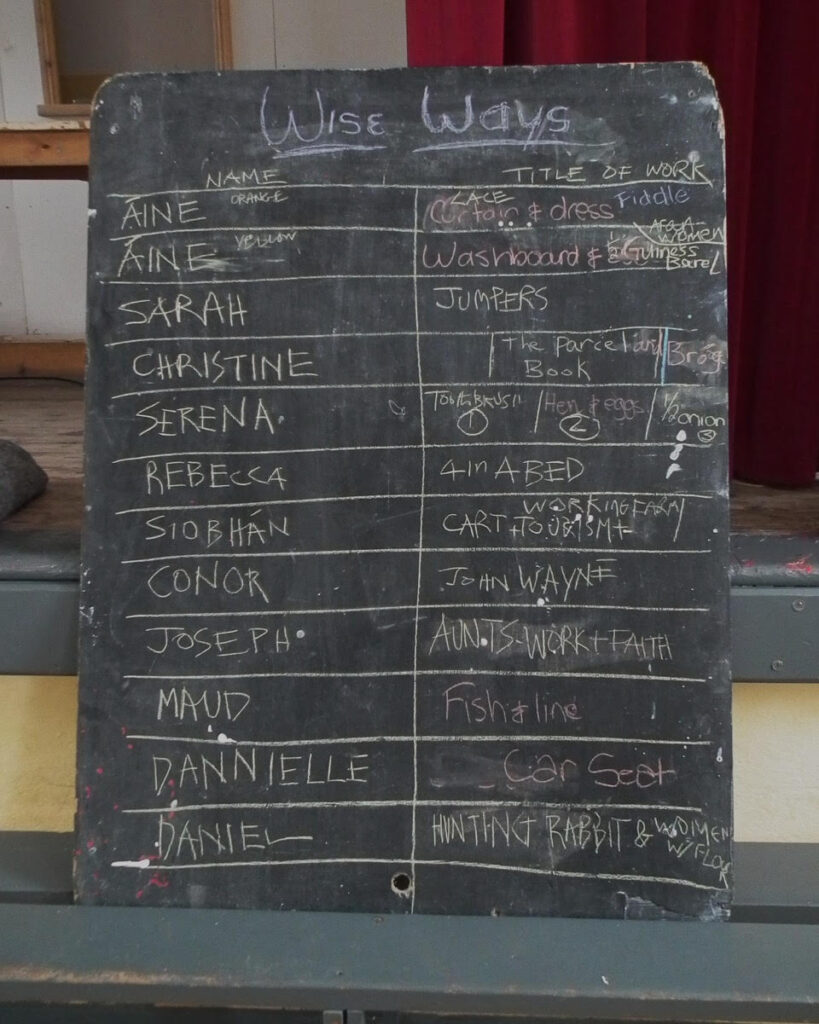

Other projects to emerge include: Mapping;16 Dreams in the Dark,17 Wiseways, and Equivalence.18 Practices tested in IMMA influenced national policy and provision such as the national Bealtaine Arts festival for creativity in ageing. IMMA over the past thirty years continues to support artists, through its Residency Programme to engage with communities and also creates a site for showcasing the work developed through the program.19 Two recent examples are A Village Plot by Deirdre O’Mahony and the Loy Foundation, 2016, an ecological artwork, and Clodagh Emoe’s Crocosmia with refugee and asylum seekers, 2018.

In the same time period, practice has grown exponentially across Ireland and critical thinking in the field has been led by a number of significant artists, most notably Ailbhe Murphy, the artist who developed Unspoken Truths and is currently director of CREATE, the national agency that supports collaborative and socially engaged arts practice (https://www.create-ireland.ie/aboutus/people/). Other artists engaging with specific communities and employing durational practices include: Marie Brett (https://mariebrett.ie/);20 the above mentioned Clodagh Emoe (https://www.clodaghemoe.com/crocosmia-x/) and Joe Lee (http://joelee.ie/); Brian Maguire (https://www.kerlingallery.com/artists/brian-maguire) Seamus Nolan (https://imma.ie/artists/seamus-nolan/); Terry O’Farrell (http://www.artsandhealth.ie/case-studies/wise-ways/); Deirdre O’Mahony (https://deirdre-omahony.ie/) and Fiona Whelan (http://www.fionawhelan.com/). While this is not a comprehensive listing of artists it will give an international reader some insight into the current range of socially engaged art practice in Ireland. While artists have led the practice in the field, third level colleges have followed by developing post graduate courses to engage practitioners in the intellectual discourses and theoretical paradigms that have been developing worldwide.

Documentation of community arts practice in Ireland was negligible until 2004 when a consortium of three organisations came together (City Arts Centre; CREATE; and Community Arts Forum) and published a first compendium titled An Outburst of Frankness, Community Arts in Ireland – A Reader. Sandy Fitzgerald, its editor, in his forward writes: “Community Arts first surfaced in Ireland in the late 1970s, ushering in something of a quiet revolution, which has since grown into a cultural phenomenon.” The contributors were chosen not because they were professional writers or academics, but “for their experience and insight into cultural life in general and community arts in particular.“21

Some sixteen years later, it is evident that arts practices formerly called community arts have been intellectually interrogated and reflect similar movements worldwide. Ailbhe Murphy artist and director of CREATE, writing in a more recent publication Learning in Public22 describes the intention of that publication as one in which: “we wanted to reflect the dialogical nature of the work, and to prompt critical questions for the field of collaborative and socially engaged arts.” A perspective that represents the intellectual rigor that she and other artists have brought to this practice over the past thirty years. An evolving Irish practice has now become part of an international discourse and is influencing a broader understanding of this emergent field of artistic practice in a cross fertilization of ideas and critical debate.

Irish practitioners are in conversation with their international counterparts and a shared understanding of socially engaged art practice is evolving. International and Irish exchanges with the USA based Kester and Gregory Sholette, for example and Irish theorists Mick Wilson and Paul O’Neill both based in Sweden currently, and practice based European collaborations have expanded both the understanding and dissemination, through publications and symposia evaluating and interrogating practice.

Currently CREATE are leading out on a collaborative process with a number of arts organizations and academics to establish an evaluative register for work in the field. They are also preparing a compendium on socially engaged practice that will be the first comprehensive publication in the field in Ireland.

Bringing Forth the Hidden

It was during the period of the “quiet revolution,” as suggested by Fitzgerald in his review of 1970s community arts practice, when McGuinness and Masterson began their activism, as teachers and artists. In their interviews both describe how in their earlier careers they were conscious of the separation of their studio practice from the collaboration that teaching creates. Masterson, teacher/pedagogue and artist based in Ireland’s prison system applies a critical pedagogy in her teaching and has evolved her artistic practice as a socially engaged artist very slowly and incrementally over time. She says in her interview that her formative experiences working in community youth programs and latterly in the prison service as an art teacher:

…have informed my own personal development as a human being, as an educator, and as an artist evolving toward a more socially engaged practice. That process came about gradually as a way of substantiating the prison community, giving voice to new and different perspectives, increasing the visibility of a disenfranchised group in society, and working toward greater visibility and inclusiveness.23

McGuinness speaking about his evolution from textile artist to social engagement in relation to his Lived Lives project which honors the lives of some sixty two young people who have died of suicide in Ireland between 2003-200824 says: “with Lived Lives it was the impact of the research process that transformed my practice from one that was concerned with the physical art object, to one that is deeply rooted in human experience and now operates within the realm of socially engaged art practice.” He continues describing the dialogical nature of his work and its concerns:

The artworks, the physical material, are not really that important to me, but what they are important for is as a catalyst and site for conversation. Somehow, sitting among torn fabrics and threads, the conversation flows a lot easier and is much more meaningful than sitting around a table. I really see this practice as being dialogical in nature.25

Nedeljković on the other hand came to live in Ireland as an asylum seeker in 2007 having fled from Belgrade in the Former Yugoslavia which was under the rule of Slobodan Milosevic and used his skill as an artist/photographer to document both his own and others’ experiences of the State Direct Provision service. His practice has developed alongside a current wave of activism calling for change by concerned citizens and human rights activists. He states that his project Asylum Archive grew out of his two years of living in Direct Provision when he kept himself “intact by capturing and communicating with the environment through photographs and videos. The creative process helped me to overcome confinement and incarceration.”26 His personal imperative has grown into a collective and collaborative project: “Years later, I am now researching a particular time in recent Irish history – from the inception of the direct provision dispersal in 1999 to the present day – while at the same time creating a repository of asylum experiences and artifacts through the Asylum Archive website.“27

Time as a Theme / Time as Form

All three artists work in long-term practices that are durational and embedded in the communities that their work represents. McGuinness and Masterson, both native and Irish born, have many years’ experience as teachers – in Irish art colleges (McGuinness) and in the Irish Prison’s Education service (Masterson) –, and Nedeljković, a recent asylum seeker to Ireland, is an artist/activist and photographer. All share a common practice as artists. Each has personally taken on the mantle of witness and creating an archive of stories/experiences of some of the most vulnerable in Irish society today. In 2015 Ailbhe Murphy spoke at a networking day for CREATE at IMMA in a talk titled “Situation Room: Critical Cartographies for Engaged Practice”28 where she reflected on her own practice highlighting durational work and the importance of time. Again this was central to the sharing of practice as is evidenced in the 2018 trans-European project documented in Susanne Bosch’s text in Learning in Public.29 She states: “Time is the invisible material of relational work. Artists often report a lack of adequate process time, to the extent that one’s own body, finances and family are neglected out of loyalty to the artistic process.”

The amount of time spent with the community is read as a sign of quality, charging artists and curators “with having pastoral care over their publics.”30

McGuinness notes that his “[…] practice is dialogical in the sense that it weaves together the importance of the conversations that flow through it, the durational timelines, the active audience participation, and participants themselves becoming agents for change.”

McGuinness, Masterson and Nedeljković’s work is testament to what Learning in Public draws our attention to, it takes time to build so ‘many trusting relationships. The work reflects the deep empathy that these artists have for the dispossessed and vulnerable in society. All three artists will leave a legacy of life-long advocacy work through their relentless commitment in speaking truth to power. In Art as Experience, the philosopher John Dewey writes:

Such fullness of emotion and spontaneity of utterance come, however, only to those who have steeped themselves in experiences of objective situations; to those who have been long absorbed in observation of related material and whose imaginations have long been occupied with reconstructing what they see and hear.31

Dewey’s reflection on being “absorbed in observation” evokes the qualities that are inherent in this practice that calls out injustices in society both past and present, and the need to remember and to be remembered.

Trust and Empathy

McGuinness also identifies with the need to be empathetic in his interview where he says: “Empathy would be the driving word in the process, I think, empathy as opposed to sympathy. Sympathy is when you feel sorry for somebody else, but this is about empathy when you actually relate with someone else, listen to them and feel without judgment.”32

He also talks about the importance of trust in all of the interpersonal relationships:

Trust is essential, trust between researchers, a great trust with the Lived Lives families, many of whom gave me precious objects from their children’s lives as well as told me the most intimate things. This level of trust is also about opening up the decision-making process, creating the circumstances for the participating Lived Lives families to become co-producers and co curators of transposing their private experiences of loss in the public domain.33

Masterson in her role as a pedagogue and teacher cites as one of her influences the American feminist/activist bell hooks whose writing about practice have informed her work. She also speaks about the importance of time in building up trust in her relationships with her students.

Memory and the Archive

Memory, for migrants, is almost always the memory of loss. But since most migrants have been pushed out of the sites of official/national memory in their original homes, there is some anxiety surrounding the status of what is lost, since the memory of the journey to a new place, the memory of one’s own life and family world in the old place, and official memory about the nation one has left have to be recombined in a new location.34

All three artists foreground the importance of defining a sense of personal and collective identity through the work they make. It is central to Masterson’s work with prisoners and dealing with the effects of long-term incarceration on the human spirit, as many of the men that she works with are survivors of institutional abuse. Her work is a personal response to their betrayal of trust. She has stated that her artwork:

[…] focuses on the past through the collective consciousness of a repressed national psyche, we are confronted with not just our own visceral national reality, but with the reality of others who have become displaced and dispossessed – the profound stigma that remains and the confused nature of identity.35

McGuinness talks about how working with the memory of young people who have been lost to suicide is about honoring their memory and reconstructing a sense of each person’s identity through the interweaving of conversations and collection of personal objects.

Nedeljković states:

It is to run after the archive… It is to have a compulsive, repetitive and nostalgic desire for the archive, an irrepressible desire to return to the origin, a homesickness, a nostalgia for the return to the most archaic place of absolute commencement.36

His practice is also collaborative and he invites asylum seekers, artists, academics, civil society artists, among others, to create “an interactive documentary cross-platform online resource, which critically foregrounds accounts of exile, displacement, trauma, and memory.” His aim is to include as many of those impacted as possible in the creation of an online repository of Direct Provision. Anne Mulhall in her essay contextualizes Nedeljković’s work both as an activist and artist in our contemporary time of turmoil. She places his art’s practice as part of the educational turn in the wider field of socially engaged arts practice, political art, and art activism.

McGuinness talks about how it was almost accidental or tangential to his working process rather than predetermined as with Nedeljković that an archive has come into being. He says that:

[…] as a result of the Lived Lives process unfolding, an archive came into being – cloth, material objects, sounds, and stories. Again this was not anticipated. The participating families were invited, following informed consent, to donate images, names, and other material objects of their suicide-deceased family member to the project.

His work always responsive and collaborative has also informed his thinking about the meaning of an archive and he says: “The Lived Lives archive is indeed a ‘living archive,’ one that continues to grow as the work and conversations around the process continue. It was never meant to be a ‘white glove’ archive. It is living, breathing, and always changing according to context, in many ways becoming a way new of working for me.”37

All three artists have assembled archives of large quantities of material; personal and family testimonies, items of clothing, personal memorabilia, responses to the workshops at each exhibition; audio recordings in McGuinness’ practice; videos and drawings by and with prisoners from Masterson and Nedeljković’s photographs “originally started as a coping mechanism” now the Asylum Archive memorializes and historicizes Direct Provision by continuing to highlight the appalling treatment of people who came to Ireland to seek protection.

Conclusion

The three artists act as interlocutors between the people whose lives they represent and the rest of society. Each one of them deal with a hidden past and present in Irish society revealing what has been/is hidden – the histories and contemporary legacies of injustice and ongoing stories of shame and social stigma. Through their respective practices, assimilation of experiences, transformation of these experiences into artwork, and dedication to the creation of an archive, each of these artists give so much of themselves. The work bears witness to the fear and fragility of young innocent children who for decades were ignored and their stories unheard, to the pain and anguish of the surviving families of young people who have committed suicide, and to the ongoing and disgraceful treatment of people seeking refuge in Ireland. The interviews and Mulhall’s essay in this case study capture the critical role that these three artists perform and how each one of them, personally and professionally have attempted to map out, collate, chart, and capture the human experience of youth suicide; incarceration; and recent asylum seeking in Ireland.

These three artists work in long term durational practices each embedded in a particular community or a set of concerns working to challenge the issues that effect and suppress that community and through their work not only have they revealed what has been, and continues to be, hidden in Irish society but their work also constitutes significant archiving of experience and life stories of citizens of the contemporary Irish State.

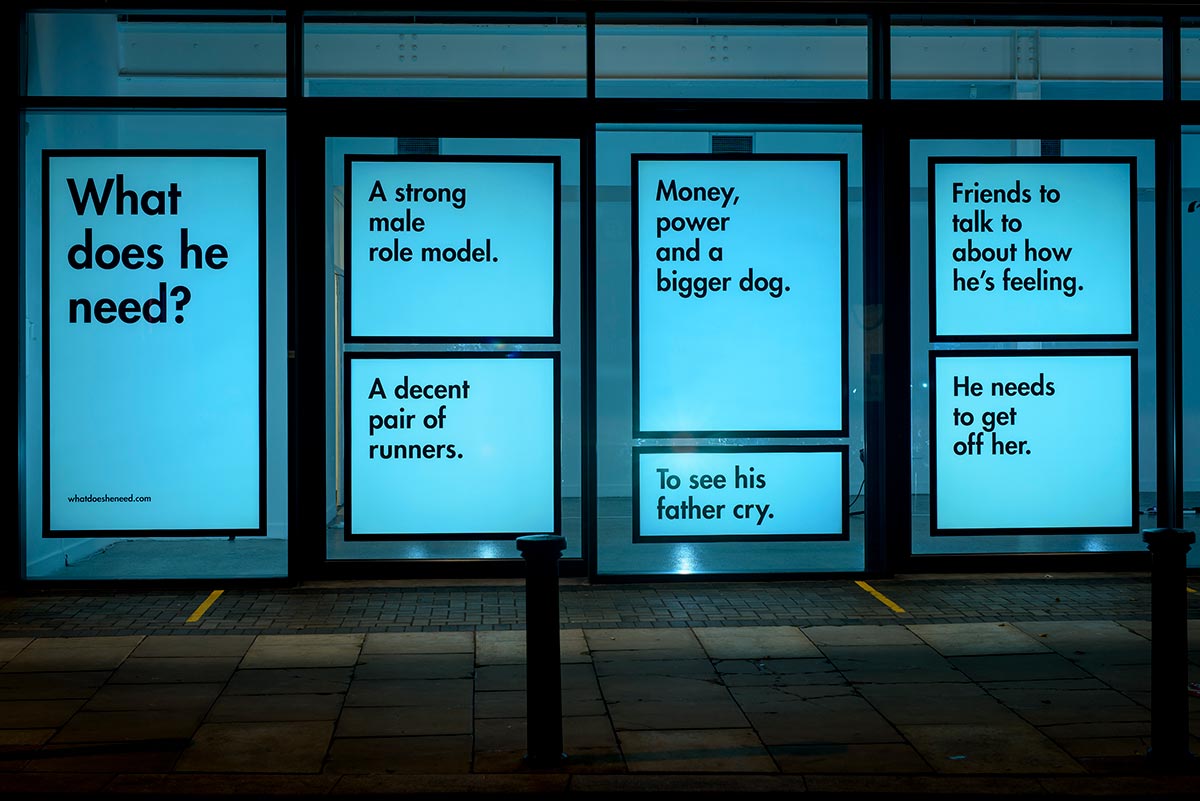

Generally, Ireland could benefit greatly from people becoming kinder towards each other.

Melatu Uche Okorie38

The statement by Melatu Uche Okorie, in its simplicity and rawness, is startling to this writer as it encapsulates in one phrase everything that most Irish people believe they are not. Irish people rather see themselves as having a worldwide reputation as a welcoming nation with the tourist tagline of being an “island of a thousand welcomes,” or a “charitable” race, being generous givers to charity. In her recent publication, which is her first collection of fictional stories, about her experiences as an asylum seeker, Melatu Uche Okorie, challenges this national preconception.

Artists such as Masterson, McGuinness, and Nedeljković presciently captured the call from Melatu Uche Okorie, to Irish people to be more cognizant of “…the need to be kind.” They and many other artists in Ireland work alongside activists fighting for an equal and just society and in so doing their work carries and sometimes articulates the voice of the voiceless, offering a tangible resonance with deeply felt emotions and experiences. Through the use and creation of archives these artists’ practices also resonate with the notable international archive created by Cuban artist, Tania Bruguera, Arte util [useful art] that gather together diverse embedded socially engaged practices working on the margins of contemporary practice.39

To quote Masterson: “Remembering the past affords us the opportunity to reflect, to take account, to change; it should inform the present” and draw attention to “[…] the reality of others who have become displaced and dispossessed.’’ Nedeljković who was housed in a Direct Provision centre while seeking asylum, described his capturing of the experience in his photo documentation as an artist “[…] helped me to overcome confinement and incarceration. ’’ McGuinness also recognizes that the power in his work and how it ritualizes and transcends the pain and trauma to “move people towards an empathic position, creating the circumstance to understand, reflect upon and question the loss of others, in a safe and dignified space.” McGuinness pointedly positions himself when he states, “as artists, we very much work in society.”

***

Helen O’Donoghue

Senior Curator, Head of Engagement & Learning at the Irish Museum of Modern Art since 1991. Recently awarded a Fulbright Scholarship she spent three months at the MoMA. Trained as a Fine Artist, she is committed to socially engaged practices and critical pedagogy both of which inform her curatorial work and writing.

1 Máighréad Medbh, “When the air inhales you “ in Unified Field (Dublin: Arlen Press 2009), p.11

2 Vukašin Nedeljković (Visual essay) Anne Mulhall (Text), “On Asylum Archive” in Revista MESA no.6 “Hidden Lives”, 2021 [Add link]

3 Vukašin Nedeljković, Asyllum Archive http://www.asylumarchive.com/

4 Helen O’Donoghue and Catherine Marshall, “Participatory Arts” in Art and Architecture of Ireland (Volume V, Royal Irish Academy, 2014) pp. 346-350

5 Ciarán Benson, Art and the Ordinary, in The ACE Report, (the Arts Council of Ireland), pp. 13-32

6 Ibid

7 Sandy Fitzgerald ed. An Outburst of Frankness: Community Arts in Ireland – A Reader (Dublin, TASC, 2004) pg.65

8 Declan McGonagle, “The Necessary Museum,”,in Irish Arts Review Yearbook (Dublin, Eton Enterprises, 1991-92)pp 61-64.

9 Helen O’Donoghue, “Come to the Edge: Artists, Art and Learning at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) – A Philosophy of Access and Engagement” in Maria Xanthoudaki, Les Tickle & Veronica Sekules (eds), Researching Visual Arts Education in Museums and Galleries (London: Kluwer Acadamic Publishers, 2003) pp 77-89.

10 Dr. Ted Fleming & Anne Gallagher, even her nudes were lovely: toward connected self-reliance at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (Dublin, Irish Museum of Modern Art 2000.)

11 Siún Hanrahan, “An Alternative Place” in Órla Dukes & Catherine Marshall eds., Celebrating a Decade (Dublin, Irish Museum of Modern Art, 2001) pp 75-81

12 Rita Fagan, Maureen Downey, Ailbhe Murphy and Helen O’Donoghue eds., Unspoken Truths (Dublin: Irish Museum of Modern Art, 1996).

13 Mary Jane Jacob (ed), with Michael Brenson, Conversations at the Castle, Changing Audiences and Contemporary Art (Cambridge, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1998).

14 Grant Kester, Conversations Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkley: University of California Press, 2003).

15 Rhona Henderson, An Outburst of Frankness – A Reader, op.cit pp.159-178.

16 Charlie O’Neill and Lisa Moran, “Mapping Lives Exploring Futures,” The Mapping Arts Project (Dublin: Irish Museum of Modern Art, 2006).

17 For Joe Lee’s work see video link https://imma.ie/artists/joe-lee/#:~:text=1958,curation%20of%20public%20art%20projects and http://joelee.ie/work/

18 For publications on Terry O’Farrell’s work see Wiseways, A Collection of Artwork in Clay with Memories from Older Generations of County Clare (Co. Clare, Raheen Hospital, 2011) and an intergenerational project https://imma.ie/whats-on/equivalence/

19 Anna Colford, “Making Space Explicit,” Conference Report on IMMA Access All Areas (8 to 10 November 2006) 2007 Visual Artists Ireland. [http://www.visualartists.ie/sfr_back_issue.html}

20 Helen O’Donoghue and Marie Brett, “No it’s not me…that’s not me…” Engage no.39, “Visual Arts and Wellbeing”, 2017 available online: http://www.engage.org/engage39, 2017)

21 Sandy Fitzgerald, An Outburst of Frankness – A Reader op.cit, p. 3

22 Eleanor Turney ed. Learning in Public, TransEuropean Collaborations in Socially Engaged Art (Dublin/London, co publishers Create and The Live Art Development Agency, on behalf of the CAPP network, 2018) p. 22

23 Bernie Masterson, “Behind Prison Walls: An Interview with Bernie Masterson” in Revista MESA no.6 “Hidden Lives”, 2021 [Add link]

24 Ireland has the 4th highest rate in Europe for males aged 15-24. The figures show that 90 people who died from suicide in 2019 were aged between 35 and 44 years old, 78 were aged between 45 and 54, and 68 were aged between 55 and 64 years old. The figures also show that 63 young people, under the age of 25, also lost their lives in this manner. George Lee Environment and Science Correspondent RTE News Friday, 29 May 2020

25 Seamus McGuinness, “Lived Lives: Conversations and Journeys through Young Irish Suicide” in Revista MESA no.6 “Hidden Lives”2021 [Add link]

26 Create News, 24, Direct Provision Diary, Vukašin Nedeljkovic, Create Ireland, www.create-ireland.ie

27 Vukašin Nedeljkovic, Asylum Archive, https://asylumarchive.com

28 https://vimeo.com/59417703

29 Susanne Bosch “Where values emerge: an in-depth exploration of the Collaborative Arts Partnership Programme’s process, discoveries and learning” in Learning in Public op.cit, pp. 60-81.

30 David Beech, “The Ideology of Duration in the Dematerialised Monument: Art, Sites, Publics and Time” in Doherty, Claire and O’Neill Paul (eds), Locating the Producers: Durational Approaches to Public Art (Valiz, Amsterdam, 2009), p. 318.

31 John Dewey, Art as Experience (New York: Penguin) p. 75

32 Seamus McGuinness, “Lived Lives: Conversations and Journeys through Young Irish Suicide” op.cit MESA no 6

33 Ibid.

34 Vukasin Nedeljković Asylum Archive website op.cit

35 Bernie Masterson and Máighréad Medbh, Bold Writing, 2016 (7 mins 17 secs) A collaboration between the artist and poet, the piece is a response in poetry and visual art to the Vere Foster’s copybooks. http://www.berniemasterson.com/

36 Vukasin Nedeljković Asylum Archive website op.cit.

37 Seamus McGuinness, “Lived Lives” op.cit

38 Melatu Uche Okorie, This Hostel Life (Ireland: Skein Press 2018) p.x

39 See https://www.arte-util.org/about/activities/