Lived Lives: Conversation and Journeys through Young Irish Suicide. Interview with Seamus McGuinness

Stigma: “sign of social unacceptability: the shame or disgrace attached to something regarded as socially unacceptable”

(Oxford English Dictionary)

While cloaked in secrecy, shame and hidden from public conversation, suicide is nevertheless heartbreakingly present. Increasing statistics worldwide, especially amongst young people, render this an urgent subject. Yet how to broach such painful memories and necessary conversations amidst challenging social stigmas? In this interview, artist Seamus McGuinness discusses his work Lived Lives, an ongoing collaborative art project that goes behind the statistics to capture stories of young lives lost to suicide in Ireland.

Lived Lives began as an interdisciplinary research platform in 2005 between the artist and scientist Kevin Malone, professor of psychiatry at St Vincent’s University Hospital/University College Dublin (UCD), and ultimately resulted in McGuinness being awarded a PhD in 2010 from the School of Medicine, UCD. Developed alongside the Suicide in Ireland Survey, conducted by Malone, Lived Lives connected with 104 Irish families bereaved by suicide between the years of 2003 – 2008, by actively listening to their stories around their kitchen tables across Ireland. The resulting exhibition, drawing on donated objects and portraits of those lost to suicide together with artworks made by McGuinness has travelled to various venues across the country, stimulating community conversations, events, and discussions. Using innovative research methods informed by richly collaborative and open community-based processes, the project deployed art as an e/affective agent to engage bereaved families, extended communities, and general publics in conversation around a highly sensitive and stigmatized subject. Interviewed near his home in Ballyvaughan, The Burren, Co. Clare, Ireland, July 7th, 2017, and recently via email / Skype in order to update new iterations of the project for the purposes of this publication, Seamus discusses his journey from textile artist to the deeply involved multi-year socially engaged art practice with which he is now immersed and the rich parallels between his former work in cloth to his current one of weaving conversations.

Co editors: Helen O’Donoghue, Jessica Gogan and Luiz Guilherme Vergara

Jessica Gogan – Can you tell us about your journey from textile artist to your social practice work?

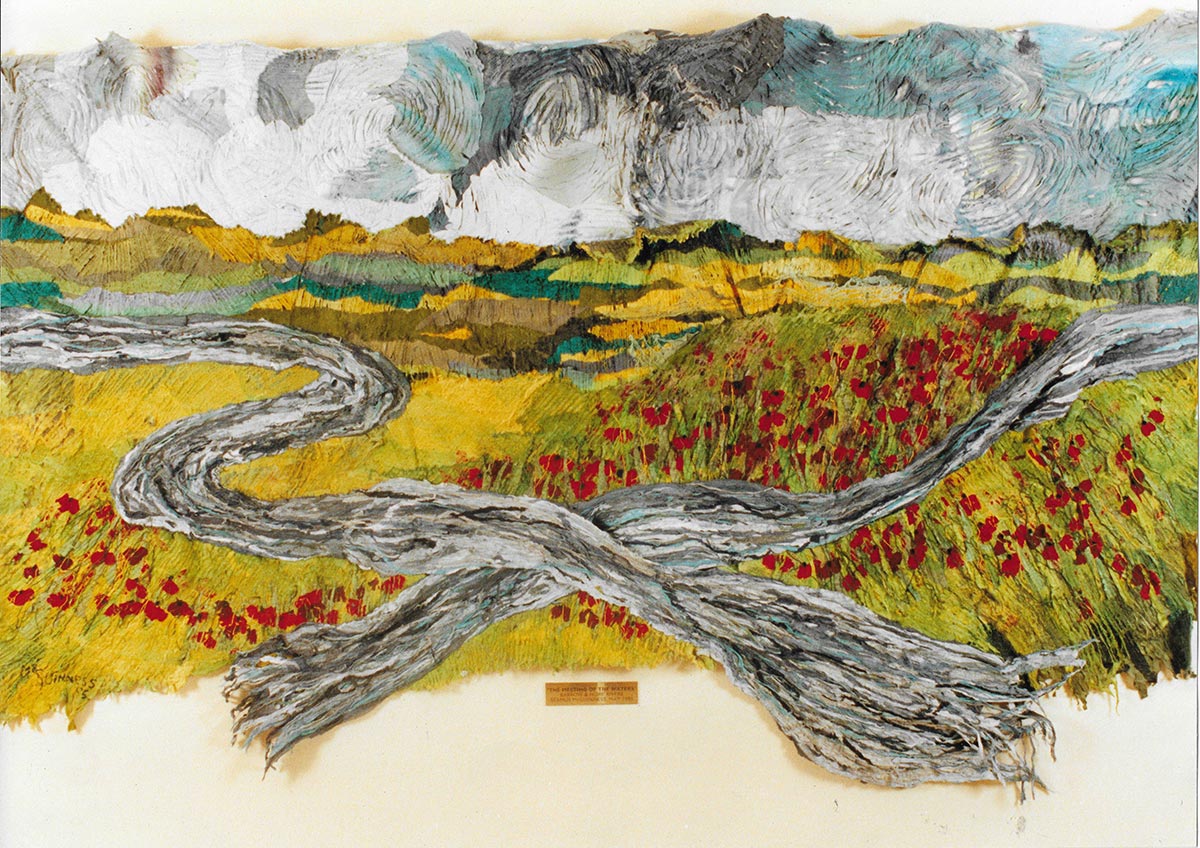

Seamus McGuinness – Cloth is not new to me; it was part of my childhood. I was raised in the Inishowen Peninsula, North Donegal, Ireland in a village called Fahan. It was a working class area, close to the border with Derry. One of the main industries in North Donegal at that time was textile-based, in particular shirt making. Both men and women were employed as textile workers. Textiles were pervasive. I went to art college from 1982 to 1986 at GMIT (Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology) and my initial art training for my primary degree was in textile design that is the exploration of cloth making and its application to the world. It was a very technical training, the emphasis being on the technical production of cloth. So I really got to know cloth’s physical possibilities. This training is still evident in my work. But now I think about cloth both as a physical material and a conceptual tool and am very interested in cloth’s ability to communicate with people and society at large. Cloth and the human body have a very shared materiality: you can cut cloth, you can cut skin, you can stitch cloth, you can stitch skin, you stain cloth, and you can also stain humans. If you stain cloth it’s quite visible, yet if you look at stigma as a stain on society, it invisible to the eye, you can’t see stigma. Stigma is felt more than seen. On graduating in 1986, like most of my contemporaries at the time, I spent a year in New York, then returned home and worked as a teacher in Dublin. On relocating to the Burren, Co. Clare, in the west of Ireland in 1991 with my young family, I established a textile studio and gallery here in Ballyvaughan. At that time my practice was very site specific, operating in the commercial marketplace. I worked in collaboration with architects, producing large-scale textile wall pieces, specifically designed and produced for public and private buildings. These were very physical pieces to make. One such example is the work Rivers, 1998, commissioned for Avonmore Diaries Headquarters in Kilkenny.

My then new home, known as The Burren – the name comes from the Irish “boireann,” meaning “great rock” – for those unfamiliar with this unusual landscape, is a region of great environmental interest dominated by glacial-era limestone hills. (For more information see: https://www.burrennationalpark.ie/).

Inspired by this landscape, I made a series of large-scale works made with thousands of pieces of hand-painted fragile cloths. For me these works were about the symbiotic connection between rural landscape and humanity. They expressed the contrast between the vastness of the Burren landscape and the very fragility of that landscape in contemporary life. The series also reflected the histories of cloth making. They were stitched together in a very intensive manner; they were very physical pieces to make. I was interested in exploring cloth’s materiality and histories of making to investigate our relationship to the landscape in which we live.

Then in the late 1990s the deaths of my parents within six months of one another opened my eyes to the possibility of my own mortality. It was my first experience of the death of a close family member and their loss affected me deeply. During this period there was a marked departure in my work practices. The experience shifted my thinking from the physical to more ephemeral concerns. This led me to question my practice and I became interested in the whole area of gender in the making of textiles. Historically the use of cloth in art making has been a very feminine pursuit. From the 1960s onwards some of the great feminist artists powerfully used women’s clothing to describe very complex female issues of their times. So I was purposely looking for something where I could use and subvert that history and I went looking for a subject matter that concerned young men in contemporary Irish society. Recalling the white shirts of my childhood, I began to deconstruct the white male shirt and the shirt collar specifically, a symbol of male conformity. It was around then that I first came across suicide statistics for young men. In 2003, for example, according to government stats, there were 92 young men aged between 18 and 25 who had died by suicide in Ireland. So I made in excess of 92 shirt collars each weighing 21g, the so-called mythical weight of the soul. (See fig 1 & 4) I installed in excess of 92 because I suspected then, now know, that due to the stigma around suicide, that other deaths would not have been reported as suicide but rather as an accidental death.

Jessica – The mythical weight of the soul? Where does this come from?

Seamus – In 1901, an American, Dr Donald MacDougall from Massachusetts, wanted to prove there was a difference in weight between a body weighed alive just before dying and a body weighed just after death. He made a study of weighing the body on a machine attached to the patient’s bed just before death and after death. Apparently, there was a difference in the two weights of “three-fourths of an ounce” or “between 19 and 21 grams,” which was taken to be the weight of the soul; his findings were published in 1907. However, despite McDougall’s enthusiasm to prove that this unaccounted-for body mass was the weight of the soul, the results are dubious. A retrial of the experiment has never been made, but the romantic idea that the soul could have weight remains.1 It is a somewhat mythic story, but as an artist, making repeat units for an art installation it gave me a kind of architectural framework to make the fragments. So this work became the installation 21 g, 2003. It measured about 3 metres x 5 metres and the collars were installed at different heights to suggest the various absent bodies. The installation of the shirt collars is recast and reshaped according to each site it occupies. The making of 21g in 2003 also coincided with the closing of the last shirt production facility in Donegal. As mentioned earlier these factories were large employers, they were communities in themselves, where generations of people worked, often entire families. When they closed, entire communities lost more than a job, often it was their collective identity, their way of life.

This context of loss and the experience of making 21 g prompted a search for other references. But I really couldn’t find much. Suicide then and still is, very stigmatized, Irish people don’t like talking about it. We’re very good about not naming things. Cancer was always the Big C, as if we couldn’t say the word. We still don’t say the word, suicide, for fear of it. Of course, it was first and foremost a sin in Irish society to kill oneself. In Ulysses [James] Joyce writes about suicides. They were buried outside the church, the ‘poor souls’ as they would say, and in the olden days, they used to drive stakes through victims’ hearts. Anyway, I was researching and I came across a conference in Dublin called “New Dimensions: Approaches to Suicide.” So I decided I would go along as part of my own research and it was there that I met Kevin Malone, who is a professor of psychiatry at University College Dublin and St Vincent’s Hospital Dublin and specializes in suicide studies. So I showed him some images of 21 g and we fell into conversation. Then we did a couple of public talks together to test the waters, so as to speak. Kevin had started the Suicide in Ireland Survey that was to adopt a psycho-biographical approach and was aimed at interviewing people who had lost relatives to suicide, so I joined him in that research. The initial research platform that Kevin and I had established operated around common research interests and was at first positioned outside any institutional framework. Subsequently, however this position was welcomed within an institutional context when in 2006 when I was appointed Ad Astra Scholar in Suicide Studies within the Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health Research, (UCD/SVUH), uniquely [situating] what would become the Lived Lives project as an art practice PhD within a Medical school. This meant that the art practice that would emerge would be one where cloth, both in its material and conceptual form, would respond to and pragmatically operate within this medical context. Clearly, it is unusual for a medical school rooted in approaches and analyses of objective disinterestedness, deemed universal and empirical, to host an art practice led PhD usually driven by personal interest and experiential hermeneutics. In the case of Lived Lives it enabled healthy points of tension between artistic and scientific approaches that in turn produced new sites of knowledge and understanding.

We interviewed 104 families across Ireland over two years, importantly, over their own kitchen tables. The prevailing thinking at the time was to bring them into the hospital, but I was acutely aware that institutions had failed many of these people and that they would be more comfortable in their homes. So we placed small ads in the free local newspapers nationally, just simply stating the nature of the study and asking those who had recently lost someone to suicide between the years 2003 – 2008 to ring the research office if they wanted to share their loss and that we would come and listen to their story. We thought we might get 20 families to participate but we actually got 104. It was a very exhausting few years. We did a lot of driving. This was an all Ireland research study, so we traveled all over the island. We decided to do one interview a day. Some would last 1 hour, others 4 or 5 hours. We felt that if someone had picked up the phone to call us, we would need to be there for them and we would stay with them. So we were very careful about when the interview started but it always ended when the families themselves ended it. Then, following their agreement and signing of the official research forms of “Informed Consent” that informed participants of the nature and parameters of the research, I invited the participating families to donate something belonging to the deceased. A lot of the families donated items from their children’s bedrooms but mostly they gave me their name and a photograph, revealing identity. This became very problematic in the School of Medicine because anonymity and confidentiality are the cornerstones of medical research so any project that emanates from the hospital or university has to have approval of the Ethics Committee.

Set up in the 1960s, Ethics and Medical Committees aimed to protect the well being of human participants in medical research. We had to present three times before they gave us permission. Like all research projects within the medical school, Lived Lives was under the jurisdiction of this governmental body. Permission to include identity in the research was refused on two occasions, primarily due to concerns over distress to extended or estranged family caused by the exposure of the identity of the deceased loved one in a public exhibition. In response, the Lived Lives process adjusted to include private exhibitions and engagements with works in progress for extended or estranged family before any public showing. It was enshrined in the working protocols that participating families could withdraw anything or everything at any stage without judgment or censure. An important voice in this navigation of ‘officialdom’ was a member of one the participating families who addressed the Committee on our 4th attempt to receive ethical approval. She argued for her right to give permission for the images and objects that she owned to be used in our research and radically, as research subjects themselves never address such committees, a pathway was provided for her to address the Ethics and Medical Research Committee personally. Permission was then granted to include images and other items that disclosed identity, if the families so wished. A series of art installations in progress were made from these donations that were initially presented back to the families for private engagement, reflection, and feedback. Importantly, as the families were present and active within the emerging artworks, listening became intrinsic to the project and the conversation that flowed through the creative process was valued as much as the making and presentation of physical works. In progress art installations were first presented to the families in 2009. It took us almost 2 weeks to ensure that every family could see the works being presented privately, as per what became to be known as the Lived Lives protocols.

The works in progress were installed in the Creative Arts and Media Centre, GMIT, Galway. The building was a former seminary for training Catholic priests, so there was enough rooms, all exactly the same size. They are now used as studios for students but were actually former sleeping cells of the priests. That the rooms were equal size was important to me because I didn’t want to privilege one family over another. Every family, every work had to have the same physical space, it was participant driven. When I made 21g in 2003, I made it as an art object, for the public to interpret in whatever way they responded to or didn’t. I feel sometimes as artists we don’t consider audiences. We often make work for fellow artists, or cultural institutions, far removed from ordinary life. Now I would question why I would do that. Going back to your original question about my journey from textile artist to social engagement, with Lived Lives it was the impact of the research process that transformed my practice from one that was concerned with the physical art object, to one that is deeply rooted in human experience and now operates within the realm of socially engaged art practice.

The layout of the exhibition and reception changes with each audience and physical site. This shift in my work practice was not a conscious decision on my behalf. It was just the way things unfolded. I followed the process. Since the first showing of Lived Lives we have continued to bring the project to different contexts throughout the country.

Helen O’Donoghue – Seamus given the way the process has, as you say “unfolded” and the broad reach throughout the country this work will have a powerful legacy. You have become and are the custodian of the stories and objects that families have donated and are slowly building a major archive. How might you see your work as an archive? With the current drive in society to digitize archives, is this something that you have given consideration to? What are your thoughts on where the archive should be based?

Seamus – As a result of the Lived Lives process unfolding an archive came into being – cloth, material objects, sounds and stories. Again this was not anticipated. The participating families were invited, following informed consent, to donate images, names, and other material objects of their suicide-deceased family member to the project. Their donations also include narratives of the deceased. These donations have become a working archive, constantly being added to, similar to what scholar Matthew Winzen refers to as “living archives,” meaning “works, which are open ended, unfinished and unfinishable.”2 Issues such as the housing and maintenance of the archive now need to be re examined. The Lived Lives archive is indeed a “living archive,” one that continues to grow as the work and conversations around the process continue. It was never meant to be a ‘white glove’ archive. It is living, breathing always changing according to context, in many ways becoming a way new of working for me. Through the process of selecting, installing, touching, and contemplating, the objects are re cast and represented in different installations and contexts at each event /showing of Lived Lives.

Visitors and invited participants to these events are encouraged to pick up items, touch them, and this act of touching provides the viewer with a pathway in. The act of touching is important. It draws on the innate quality of cloth to be communicative and a vehicle for transformative aesthetic encounters and these encounters in turn also become part of the archive via the documentation process.

Presently I house all the physical archive donations and works in my private studio, next to my home, I hold them in trust. However, I do not want this archive and future works to consumed by an institution: it should always be owned by the people whose experiences of loss it strives to articulate and be accessible to others. An alternative option would be to digitize the entire archive, return the donations to the families, and let it exist as a web presence, but then the act of physical touch would be missing. So questions and dilemmas with respect to the archive are ongoing concerns for the project.

Jessica – It’s fascinating to think about how the “living archive” reflects a living contemporary Ireland. Perhaps you could talk how the different audiences you work with in this regard.

Seamus – We aim to engage many publics: youth, of course and marginalized communities, often disproportionately impacted by suicide as well as diverse audiences by working closely with local partners on the ground. One of the iterations of Lived Lives took place in Fort Dunree, Inishowen, a rural area in Co. Donegal, in 2017. Here, the audiences we worked with were mainly 16 years olds. In this kind of research, generally researchers do not engage with under 18s about suicide because they are not adults, it’s not a done thing. But in fact 16 – 18 years are a population at high risk. Indeed the youngest person in our Lived Lives archive is Rebecca, she was 14 when she died. In one of our mediated talks at Fort Dunree one girl asked if 14 year olds are killing themselves why can’t our voice be part of this conversation. I thought to myself, yes, that makes sense, so we have started including them too, ensuring their normally unheard voice is spoken out loud. This kind of engagement involves working very closely with the schools. We visit schools in advance to ensure everyone is aware of the nature of the work before students visit. Directly involving these young people in this way seems to be a very good model of engagement. They can articulate things in language that 14 and 16 years olds can understand. Regarding suicide we tend to talk very much like adults about this, so it’s critical to create both aesthetic and ethical platforms for these young voices to emerge.

In addition to youth, in Ireland, another disproportionately high risk group are Travellers. [Travellers refer to communities that share culture and traditions predominantly marked by a nomadic way of life].3 So in 2015 a version of Lived Lives was presented at the national Traveller Resource Centre, Pavee Point, Dublin. The exhibition aimed to create awareness about the challenge of elevated suicide rates within the Travelling community. In a similar way to what I described working with youth audiences, the exhibition process also involved a series of mediated visits and discussions. (See Pavee Perspective at https://www.livedlivesproject.com/)

We were fortunate to receive funding from Wellcome Trust to support the Pavee Perspective and this was followed by a second grant in 2017 aimed at, over a twelve-month period, reaching new rural and marginalized communities in five different venues. Importantly, it was not just about working with communities on different fringes of Irish society, but critically we strove to bring these groups together and create dialogues amongst these groups with representatives from diverse institutions. Here perspectives that might be seen as geographically and psychologically opposite are brought together linked by their common experiences of suicide, stigma, and marginalization. For example, a first responder or Garda Siochana [Police] being called out to and on arriving on the scene of a suicide, LGBTI youth and community members, also disproportionately impacted by suicide, bereaved families, local media, and mental health professionals. Open dialogue that doesn’t pity, fetishize or present participants as victims or statistics can move people towards an empathic position. The goal is to create the circumstances to listen to different stories and to understand, reflect upon, and question loss without judgment. This sense of the Lived Lives project creating sites for conversation, reflection, and contemplation across different interests was particularly poignant in its iteration at the psychiatric hospital St Patrick’s University Hospital in Dublin. This iteration became known as From Tory Island to Swift’s Asylum. Art pieces were installed throughout the hospital and we gave audiences mediated tours. Importantly, we presented at the Founders Day Conference, where we were able to bring together mental health service users with providers and policy makers – a rare, if not unheard of occurrence. We also hosted conversations in the Hospital Board Room and encouraged reflections on Lived Lives from clinical staff and evaluators. It is truly moving to see how these mediated exhibitions/events have the power to engage and be relevant to diverse groups. (See From Tory Island to Swifts Asylum at https://www.livedlivesproject.com/)

But I think to explain our process it’s useful to go right back to those private engagements and viewings with the families during the first installation of Lived Lives in Galway 2009. During the first week each family was guided through the works in progress. It was a process of conversations and journeys. At this stage the families had not met each other. The idea was to do private viewings with each family separately. We were extremely careful about this and created a timetable to ensure they each had this private time. Each journey through the works took about 2 hours. We recorded all the conversations, then transcribed them and gave copies to the families asking them to block out anything that they didn’t want made public. Because you know sometimes in conversation people might mention names and stuff and think afterwards maybe I shouldn’t have said that etc. I wanted them to have ownership of how their private experiences of loss would enter the public realm. We were always very careful. We moved very slowly through what was often reliving a very tangible grief. It was a trust building exercise. This is a method in my process and reflecting on it now, I would say it’s been a key part of the research and has continued to be as we bring the works into the public domain. The entire proceedings, journeys through the art installations, reflective conversions, and discussions were documented via both still and moving image, which provides a pathway for the families to engage with their grief in documented form and, in their own time, edit what is shown to the larger public and, in so doing, critically extending the conversation beyond the immediate participants. In Lived Lives both for the families and general publics the experience as they move through the works, physically touching, and marking the art works is central to the process, and it has often been described as transformative.

Jessica – Listening to you describe this incredibly ethical and careful process, I am reminded of a comment in your recent epublication noting that in much socially engaged practice, however well intentioned and/or driven by social and community concerns, the artist, nevertheless remains “sovereign”4 which is very different from your process.

Seamus – I feel often in contemporary art the voices of the public and participants are not heard. Instead we hear the voices of artists, educators, critics, and curators. Frequently in socially engaged practice, artists who work with communities say, we are trying represent those communities. But, in fact, we often don’t involve these same communities in decision-making processes. Here, the families decided everything and this continues. At the end of that week in Galway in 2009 where we first showed Lived Lives, we called all the families together. The focus of my PhD was to explore how could we create the circumstances to release these private stories into the public realm. A big part of that was asking the families themselves, not only if, but also, how we should do this. So at this meeting, the first time they all met, the families decided they indeed wanted the works to go public and they recommended four curatorial (although they wouldn’t have said curatorial but they were) strategies as to how we should go about making the works public:

- 1st — works should always be mediated

- 2nd – not to privilege one family over another, so every time we show the works there’s at least one object from every family

- 3rd — ensure there is bereavement support on hand — so every time we have an exhibition we have bereavement counselors. You never know who is walking in off the street and how they might be affected.

- 4th – under 16 should not see this unless they are accompanied by an adult or a guardian

Once these strategies were put into place, and we have continued to work with them all the time, it really shaped how we work, but of course, it makes any exhibition a long slow process. When we show works in public I generally give the mediated tour of the works, it takes about 90 minutes.

After the journey through the works we then come back to the exhibition space and sitting amidst the artworks have a conversation about suicide in Ireland. The artworks, the physical material, are not really that important to me, but what they are important for is as a catalyst and site for conversation. Somehow, sitting among torn fabrics and threads, the conversation flows a lot easier and is much more meaningful than sitting around a table. I really see this practice as being dialogical in nature.

Another important aspect of the process is evaluation. We always invite audiences who engage with the works to give written feedback. We have thousands of completed forms, adding to the archive, by now we have shown in over twenty venues and sites. One of the questions we ask is do you think this romanticizes or glorifies suicide, which is a question whenever you have aesthetic elements involved you have to consider, but the answer we get back is no, not all, it doesn’t at all, it’s just real.

But we don’t only conduct written feedback. Now, whenever we stage exhibitions and events, evaluators are an integral part, they are there to observe. We always try to have someone from the art world and the medical world. We constantly strive to have this balance, and in doing so to also have this interdisciplinary conversation between art and science. So we have three lenses of evaluation — art, science, and the communities that we work with. (See Part III: Lived Lives: Independent evaluations, Feedback, Radio interviews and Culture Counts at https://www.livedlivesproject.com/)

Another thing that we do is to request, whenever we were working with anybody from officialdom, anyone from an institutional context, that they leave their institutional hats outside the door, and meet people as people. Often institutions suppress the goodness of people and they tend to talk from an institutional point of view rather than a human one. You have to shift out of that professional tone, in order to have a conversation about humans among humans.

Each time we do an exhibition, the first day or opening day is always a closed day, that is, only open for the Lived Lives families and those suicide bereaved families from that local community. So it’s just for them. The donating families often join us in this process. It is always very intimate, very sad, they know what it’s like, they’ve all been through it, it’s a therapeutic process, or rather, I might say it’s a cathartic experience more than a therapeutic experience.

Guilherme Vergara – This incredibly thoughtful and careful process reminds me of this Japanese film Departures (2008). A failed concert cellist, returns home to a small town and the only job he can get is as a traditional Japanese ritual mortician — a kind of embalming. He’s subject to prejudice due to various strong social taboos about those who deal with death, but he performs his job with such care, detail and love, like playing music, he brings dignity to death.

Seamus – Yes, trust, care, one thing that really struck me is that these 104 families suffered possibly the worse thing that could have happened to them in their life so far, yet, they were quite willing to share their stories to someone else who didn’t go through it and to me that’s the essence of humanity. I always try to hold that very carefully. I think when you are working with communities and individuals, there’s no point in just exposing them to an art process, you actually have to place them within it and trust builds from this. Lots of projects bring people along, but don’t let them make decisions. For us, the families have to have the say in everything we do. What’s interesting is that, in opening things up and letting go of control, they always end up adding to the process in unexpected ways.

Jessica – So it becomes an aggregative process?

Seamus – Yes. The first families we spoke to in 2006 are still involved in the process. A lot of the families have become friends among each other and with us as well. And it’s not all sadness. Our proximity to each other and the trust that exists between us has resulted in close friendships and respect.

Jessica – I’m struck by the parallels between your work in textiles and your social practice. The whole process you describe seems to me like one of cloth making — a weaving of care and conversations…

Seamus – Cloth communicates in the most silent of ways, we are wrapped in cloth when we are born, when we die, to keep us warm, people innately understand, it is a cradle to grave material. Cloth is a most intimate thing; cloth and skin, cloth as a second skin. The difference in my work over the last 15 years is a move from an object-based practice to a conversational-based practice through cloth. It’s calls on the shared materiality of cloth and humans. References such as The Whole Cloth [Mildred Constantine and Laurel Reuter] document the history of cloth in art and show us how cloth operates socially, medically, politically and so on. The intrinsic and essential characteristics of cloth’s materiality and its relationship with people have played a central role in the development of everyday language. The words text and textile come from the same Latin root textere meaning to weave, to fabricate. Textile terms and metaphors of cloth are deeply rooted in literature and everyday expressions: the fabric of society; communities described as closely knit; or, at the other end of the spectrum, unravelling; we weave and embroider stories; we spin a yarn; we embellish and fabricate the truth; life is often described as a tapestry; in marriage we tie the knot. We even have threads in websites or newsgroups that one can follow or join. It continues to amaze me that these terms are still used in contemporary communication. We have always known cloth. It has always knows us.

Jessica – These metaphors and practices of fabric making offer truly rich and textured ways of connecting art and life. You have described the textile industries in your community as a key early influence but I am also curious as to what was it that that got you into art?

Seamus – I had a very good art teacher in secondary school in Buncrana, Co.Donegal, a nun, Sister Enda. While you might expect that being a nun might have made her conservative, she was actually an amazing teacher. I was very shy then. The art room in secondary school was my sanctuary. As mentioned earlier, after secondary school, when I was 18, I went to the GMIT to study textiles in the art school. So really making art is all I ever wanted to do.

Guilherme – Going back to the Lived Lives project what did you discover in this process or rather in the ethics of the process? An ethics of friendship? New parameters between science and art? A model of care and trust?

Seamus – Empathy would be the driving word in the process, I think; empathy as opposed to sympathy. Sympathy is when you feel sorry for somebody else, but this is about empathy when you actually relate with someone else, listen and feel without judgment. Trust is essential, trust between researchers, a great trust with the Lived Lives families, many of whom gave me precious objects from their children’s lives as well as shared with me the most intimate things and details of their children’s lives. This level of trust is also about opening up the decision making process, creating the circumstances for the participating Lived Lives families to become co-producers and co-curators of transposing their private experiences of loss into the public domain. In addition to listening, inviting them to be part of the decision making process they are also part of the curatorial editing process. For example after every event we produce short documentary videos. In Lived Lives Galway ’09 we had filmed the families engaging with the work in progress and in the editing process we showed them the material, so they could edit what was to be presented and have a say and stake in that process as well. This close relationship between myself, as the artist, and the families, keeps building the trust. It is a tried and tested method.

I have always been aware of the highly emotional content in some of these small video works. So far, people rarely want to edit things out. I remember once, in the early stages, I was showing one person a very intense grieving moment, she was very emotional and afterwards she joked about airbrushing her arms, she actually said nothing about the emotional content.

There’s also a great sense of care. The families, they care for each other. Also amongst ourselves as researchers, whenever we are installing the exhibition in various locations, we care for the team. Everyone looks after one another. We all share accommodation. We eat together, talk through the events of the day. This spirit is really important, even though the wider team has been working on this project for years; there are times when we too are emotionally and physically challenged. It is so important that we look after each other.

Jessica – What about yourself? I can imagine how intense this whole process must have been for you. What do you do to nurture yourself, to take care of yourself?

Seamus – Initially when we started the process of interviewing, after every six interviews we underwent psychological supervision. My wife Orla is a psychotherapist and she really encouraged me to talk it out a lot and write it down, work through it, process it.

At times it was tough going. Of course you’re always thinking this could be my child. At the beginning I would return home, after interviews, often late at night and would go into my own kids’ bedroom and I had to see them breathe. It’s very emotional. You understand that this could happen to any child, including your own.

Jessica – I can only imagine how emotion this must have been.

Seamus – Some of the most poignant and difficult moments in this process occurred when I was together with the families in the bedrooms or outbuildings where the death took place. Often these sites of death remained unchanged, captured in time, and frozen by grief. By being present their stories seeped into my person. Personally it was challenging, difficult and at times heartbreaking to sit for hours as a parent or sibling described how their child/brother or sister killed themselves, and their personal struggles in learning how to live with that loss. It was humbling that they in various stages of grief were prepared to share their stories and give me precious items belonging to their dead children. In many of these family stories and engagements I have glimpsed the essence of humanity. By this I mean that these people willingly invited two strangers into their home and relived the horrific moment when their child/sibling hung, shot, drowned or overdosed themselves, some recounted going into their child’s bedroom and finding them dead. This is the stark reality of the terrain that Lives Lives navigates. In many of these the beauty and tragedy of human life was revealed to me. Those unique moments of interpersonal engagement illuminated to me the complexity and fragility of human existence and communication. It has been a privilege to be present to and to witness this essence of humanity, the ability to rise above personal tragedy in order to help another person. What humbled me, and this has had a deep effect on how I see the world, is how these people in the depth of their loss could actually think of others. This process has changed me fundamentally in the sense that I have learned to listen to the other without judgment. As a direct result of these experiences I have developed unexpected skills that enable me to relate empathically to people, to listen in between reality and imagination. I have discovered a capacity within myself to be entirely present to others in their sorrow and the ability to hold a safe space for their stories to emerge. This is now as important in my work practice as the making of textile artifacts. Within myself I have developed the capacity to meet each participant – and myself – where we were at that moment of life.

But perhaps it’s important to ask what do we learn from all this and what can we do? We are in a very dangerous place. In Ireland, we have this culture of awareness concerning suicide, but we haven’t moved on. If we don’t move on from a culture of awareness to a culture of knowledge and action, this process is futile in many ways. Suicide rates are still increasing with the high risk years between 14 – 23, statistics internationally are 75% male, 25% female. I think we need to teach our kids to be more resilient that despite how it feels at the time you can get through this, but also, that dead is dead, there’s no coming back. We also need to make this visible. How can we do this using the context of the art world?

Guilherme – Do you think this methodology could be applied to other issues as well? Not only suicide?

Seamus – I think this methodology could apply to any situation where stigma or shame operates and perpetuates silence. It creates a process of sharing and mutual respect, without judgment particularly amongst marginalized groups who don’t have a voice. I think that, if the methodology isn’t transferable to other areas of human life, where stigma silences action then I would have to question it. In Ireland we have a poor record of recognizing people with mental health problems, they do not have a voice, there has been little meaningful action to try and understand the beauty and power of that fragility.

Lived Lives is an exhibition about death but it’s also about life, how the families live afterwards. I don’t like the term exhibition that much, as it suggests something passive. What we do are rather events; it is a process of donating, not consuming. We have the audience touch the works, they leave their marks, they touch the artworks, hear and feel the stories, they share that experience with us on camera, in public.

As artists, we very much work in society. We need to re-frame our questions as the critic Declan McGonagle notes, in terms of not what are artworks but rather what can artworks do in society. Part of this is also about developing a language that people outside the art world can understand. The world needs artists. But we need to address elitism in particular regarding the language we use, such a complicated language has evolved around our practice.

Jessica – Science too…

Guilherme – Yes, every profession has its language…knowledge is structured by language. But perhaps via your art/science hybrid, you can deny the domain of each one, to create another one…

Seamus – I think it is important for artists and indeed scientists to speak outside their own sector/discipline, to speak across boundaries, to be heard in wider society as well as within their own culture. I would lean towards a language that is meaningful in other sectors of society but one that still articulates the value and meaning of art practice. When Kevin and I started to work together, we quickly realized that we had a shared research area but our languages and approaches were completely different. We wondered if we stepped outside the comfort and familiarity of our disciplines and language could we craft an alternative language to articulate the ominous present of youth suicide in Ireland. We knew that we shared a common research subject matter, i.e., young male suicide but we struggled to understand the official languages of art and science. This was really important for both of us. Chicago based curator Mary Jane Jacob talks about being an outlier — working outside the mainstream, yet bringing the insider and outsider into active dialogue, with an emphatic and non judgmental ear, collectively crafting a new dialogue.5 I would ague that this new dialogue or way of communication in Lived Lives comes first from an aesthetic tradition; secondly it is influenced by scientific/empirical methods; and thirdly it is rooted in “life” operating alongside theory. It is not contained within theory but seeks to open up closed down pockets of conversation and tacit knowledge. In his essay The Real Experiment Continues, Jan Estep states: “There are two axes along which art moves: towards art and towards life”.6 Lived Lives operates somewhere between these two axes, sometimes pulled towards art, other times gravitating towards life situations. Pushing in one direction, art becomes a rarefied phenomenon, separate from life and autonomous in its pursuits. Pushing in the other direction as Estep notes “art increasingly blurs the boundaries between itself and life, challenging our ability to distinguish the two.”7

My practice is dialogical in the sense that it weaves together the importance of the different conversations that flow through it, the durational time lines, the active audience participation, and participants themselves becoming agents for change. I see my work as a kind of ritual performance. There’s a physical journey, walking through and touching the artwork, — a beginning, middle, and end — and an emotional journey — feeling instead of thinking, seeing things in a new way. The works are not solidified like a proof-of concept. Nor are they scientifically proven. They are fluid moments in time, an in-between space where the tensions between the tangible material and crafting and the conceptual and symbolic meaning of cloth come into being. However, the families’ personal, and at times visceral, engagement with the works could be described as a sort of needle that pierces through that moment, or what Barthes would call a punctum, a lived action – or in Levinas’ words “the needle touches and pierces life.”8 It is the point that pricks you. It could be anything but once it is pricked, you have opened a channel or duct and you must process and act on it. The aesthetic experience of Lived Lives has the quality of a ritual or relic, but its primary quality is the manner in which it is communicative. The practice can move people towards an empathic position, creating the circumstance to understand, reflect upon and question the loss of others, without judgment in a safe and dignified space.

For further information on the Lived Lives project: www.livedlivesproject.com

***

Seamus McGuinness

Irish artist, researcher and educator. He lives and works in Co. Clare, on the West coast of Ireland and lectures in Contemporary Textiles at Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology. His practice is deeply rooted in life and cloth, encompassing trans-disciplinary research, durational social intervention, interactive installations, public conversations and collective democratic acts. In 2010 he was awarded a PhD for the Lived Lives Project, from the School of Medicine, University College Dublin. He has been awarded two Wellcome Trust Grants in 2015 and 2018 to continue this research.

Additional References:

Jefferies, Janis ed. Reinventing Textiles: Gender and Identity Vol. 2. Winchester: Telos Publica-tions, 2001

Livingstone Joan and Ploof, John eds. The Object of Labour: Art, Cloth, and Cultural Produc- tion. Chicago: School of the Art Institute of Chicago Press, 2007.

McGonagle, Declan. Passive to Active Citzenship: A Role for the Arts, Bolgona in Context Conference Dublin Ireland, 2010.

Parker, Rosaline. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. London: Women’s Art Press, 1984

1 Ian Sample. “Is there Lightness After Death? Guardian, 19 February, 2004, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2004”/feb/19/science.science [Accessed 10.07.2020]

2 Matthew Winzen, Living Archives in Matthew Winzen and Ingrid Schaffner eds. Deep Storage. Munich: Prestel, 1999, p.44

3 In Ireland, communities sharing this nomadic way of life are known as the Roma community consisting of persons from a range of European countries and Travellers. Both communities have suffered a long history of multiple and intersectional discrimination including poverty, unemployment, lack of educational opportunity, decreased life expectancy, cultural bias, and social stereotyping. Since its foundation in 1985, the Pavee Point Traveller and Roma Centre has recognized the need for solidarity between Roma and Irish Traveller communities based on their shared experiences of racism and social exclusion. For more information: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/31029/1/National_Traveller_and_Roma_Inclusion_Strategy_2017-2021.pdf [Accessed August 2020] https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/31029/1/National_Traveller_and_Roma_Inclusion_Strategy_2017-2021.pdf [Acesso em ago. 2020]

4 Lived Lives: From Tory Island to Swift’s Asylum (2017-2019) Epub, 2020, p69 [Accessed Lived Lives website www.livedlivesproject.com October 2020]

5 Mary Jane Jacob in conversation with Seamus McGuinness. For a brief overview of Mary Jane’s practice see Monika Molnár and Tanja Trampe. “Public Art: Consequences of a Gesture? An Interview with Mary Jane Jacob” Oncurating “On Artistic and Curatorial Authorship” Issue 1, 2013 https://www.on-curating.org/issue-19-reader/public-art-consequences-of-a-gesture-an-interview-with-mary-jane-jacob.html#.XzrvE5NKiuW [Accessed August 2020]

6 Jan Estep, “The Real Experiment Continues,” Art in the Life World Research Papers. Ballymun, Dublin: Breaking Ground, 2008) p.7

7 Ibid.

8 Barthes, Roland. Mythologies, translated by A. Lavers (London: Vintage, 1993) p.23

and Emmanuel Levinas. Outside the subject, translated by M.B. Smith (Californa: Stanford University Press, 1994) p.38