Casa Museu Rancho Verde: An Idea, A Utopia, A Field under Construction

Priscila Grimberg e Maria Ignês Albuquerque

Our civilization is in crisis. Clearly visible in the health crisis laid bare by Covid-19 and in the ecological crisis, now surpassing several planetary limits,¹ especially with respect to the loss of biodiversity, and fully manifested in climate change.² A “policrisis,” as noted by the philosopher Edgar Morin³ that is primarily a crisis of values4, originating in ruptures of various orders between man and nature, economics and ethics, and the objective and the subjective.5 Notably, these dichotomies are not compatible with the complexity and urgency of contemporary challenges, especially when it comes to the natural lottery in which the citizens of the Global South6 find themselves, like us here in Brazil.

Sociologist Enrique Leff, one of the leading Latin American intellectuals with respect to environmental issues, argues that dealing with the complexity of the planetary crisis requires a complex rationality.7 Similarly, as a counterpoint to paradigms of modern science8 Edgar Morin proposes the paradigm of complexity as a new way of establishing bridges and articulating connections between different areas of knowledge.9 Understanding the complexity of humanity and the world today, means understanding the interconnection between the one and the multiple,10 as the Latin term complexus indicates: what is woven together, a reality where everything is related, starting with our common home – the Earth. In Morin’s words, Homeland Earth, where:

The awareness of the community of earthly destiny must be the key event of the new millennium: we are in solidarity with this planet; our life is linked to its life. We must fix it or die. To assume terrestrial citizenship is to assume our community of destiny.11

To assume the terrestrial citizenship proposed by Morin12 – one that increases our social and planetary awareness – is in line with the notion of sustainability as being a field under construction, as an idea that mobilizes, and as a necessary utopia.13 For him, the transition or the metamorphosis will only be possible resulting from a change of conscience and behavior. Here, sustainability is also necessarily situated as a counterculture14 and, naturally, as an arena of disputes and conflicts.

It is in this sense that the Casa Museu Rancho Verde [Green Ranch House Museum] operates as a collective socio-environmental project and as a complex micro resistance to fragmented rationality. The Casa Museu [House Museum] developed from the encounters and assemblies at Rancho Verde [Green Ranch], the home of Seu Hernandes Jose de Silva [Seu or Mr is frequently used in addressing elders and tradespeople] located in the Morro de Bumba favela in the Niterói, a suburban city on the other side of Rio de Janeiro’s Guanabara Bay. A home that Seu Hernandes lovingly fills with recycled objects and waste that he transforms and paints green. Just as in the physical and spiritual practice of “do-in” [acupressure points] – a word of Japanese origin that literally means “the way home”, where home is the body, the home of the spirit and ki, of vital energy – we embrace together with Seu Hernandes a microgeographic practice of “do-in”. A practice advocated by musician and former Brazilian cultural minister Gilberto Gil in his political and socio-cultural vision for a national cultural policy as a form of “anthropological do-in”, that is a systemic “cellular” practice that nourishes and catalyzes existing and “hidden” potentialities in peripheral locations – outside large city centers. The collective and poetic “do-in” at Casa Museu Rancho Verde over the past ten years has led to numerous transformations at the Rancho itself, in the life of Seu Hernandes, and in ours. In the following essay, we explore these transformative trajectories and point to possible paths of existential, social, and environmental restoration via the co-creation of healing practices as a kind of “do-in” within the social fabric. In activating awareness and moving away from individualism towards a “community of destiny,” as suggested by Morin, it is possible to inspire thoughts and practices for transitions aimed at ordinary people, in common places, especially in peripheries, as is our case at Morro do Bumba favela in Niterói.15

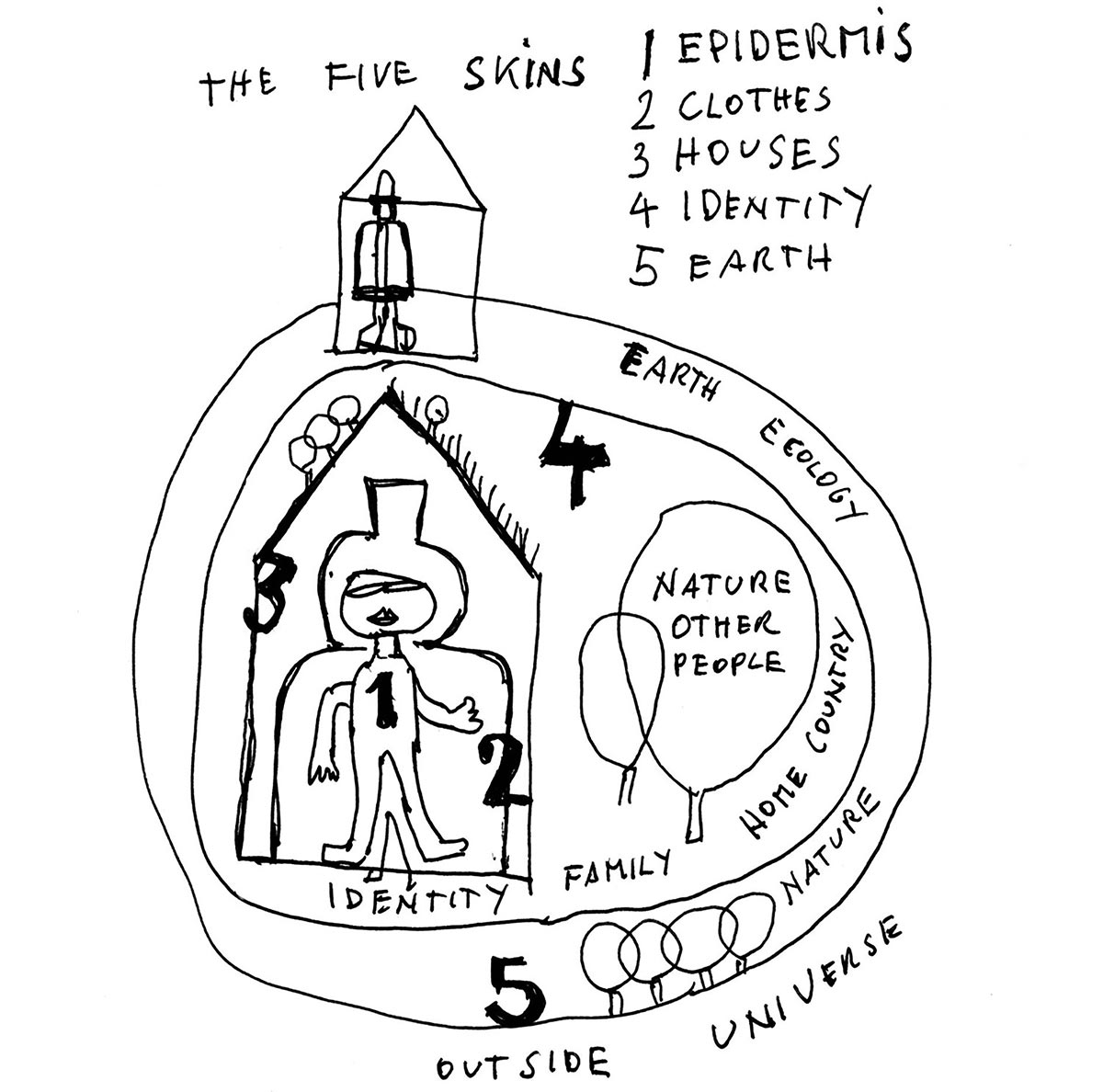

Care is our driving principle and practice, unveiling a vision that brings together different dimensions of relationships – the individual, the other, and the planet – as synthesized by the Austrian artist, architect, and activist Hundertwasser, in his design of the theory of the five skins16 (represented in the figure below). Over the past ten years we have been integrating the achievements of the Casa Museu Rancho Verde project and the knowledge learned together with a network of partners that have gradually transformed reigning modes of thinking and working (our own included). This has largely been the result of an axis of articulation of artistic and sustainable practices, merged via diverse care intiatives – micro movements of assemblies and confluences – that work against fragmentation and toward complex rationality.

Having touched upon some of the key concepts that inspire us and situated the locale from which we speak, the following briefly outlines the historical-political genealogy of the Casa Museu Rancho Verde including our trajectory up until this point, the web of initiatives developed, and collaborators with whom we have worked, and offers a small magnifying glass on how we care for our backyard. Finally, we share some reflections on the challenges, dreams, and opportunities for the future for this affective laboratory process, which we call Casa Museu Rancho Verde or, simply, Casa.

Genealogy

One day, in 2010, we crossed Guanabara Bay to meet a special person. At the time, we did not know is how much this encounter would generate experiences and convivialities, connecting people and institutions, transforming lives, and creating a network of affections and mutual care around a small green house. The Rancho Verde [Green Ranch] is a house in constant transformation where the 92 year-old Hernandes José da Silva (HJS or Seu Hernandes) lives in Morro do Bumba, Niterói. Seu Hernandes tells the story that the color green was inspired by a dream in which he flew over an immense green area and a voice said:“the green you see is the green of your hope, go home, there you have everything you need.”17 That was how the color green became part of his imagination. Painted everywhere it is a radiant magnet on the walls and all the furniture that Seu Hernandes gathered and restored and on the recycled objects and garbage found in the streets around the Rancho. Some object series can be noted such as chairs of different types, fans, watches, dolls, bottles, lights, mirrors, wooden pieces, and even toys. As you walk through this living house, you can see its aura of enchantment / painting / baptism everywhere, a ritual of entering the HJS’s world, in monochromatic harmony with the surrounding green vegetation, full of Atlantic Forest species, a botanical microcosm preserved right in Morro do Bumba, in this small backyard where we also started to dream of dreams in the form of art as resistance and social engagement.

[…] dreams open up the possibility for us to connect with collective solutions and dare a great matrix of imagination. If people don’t dream, they don’t see a future. If we see no way out, it is not because science is lacking, it is because dreams are.18

May the green the Seu Hernandes saw also be the green of our hope.

The first encounter with Seu Hernandes took place following a suggestion of his neighbor19 who, at the time, was participating in Family in Transit program, organized by Maria Inês Albuquerque (co-coordinator and co-founder of the Casa Museu Rancho Verde project) as part of museum outreach iniatives of the Núcleo Experimental de Educação e Arte [Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art] (2010-2013)20 at the Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, (MAM) in partnership with the Central de Penas e Medidas Alternativas [Alternative Penalities and Measures Center] (CPMA). The Nucleus aimed to develop strategies to foster new relations between the museum and the city and address questions such as: how to build and establish new links and affections between the museum and diverse sectors of society; how to advance or expand the sense of education beyond the modes of service traditionally provided by museums; how to access people and groups considering real life events as a privileged space for such activity?

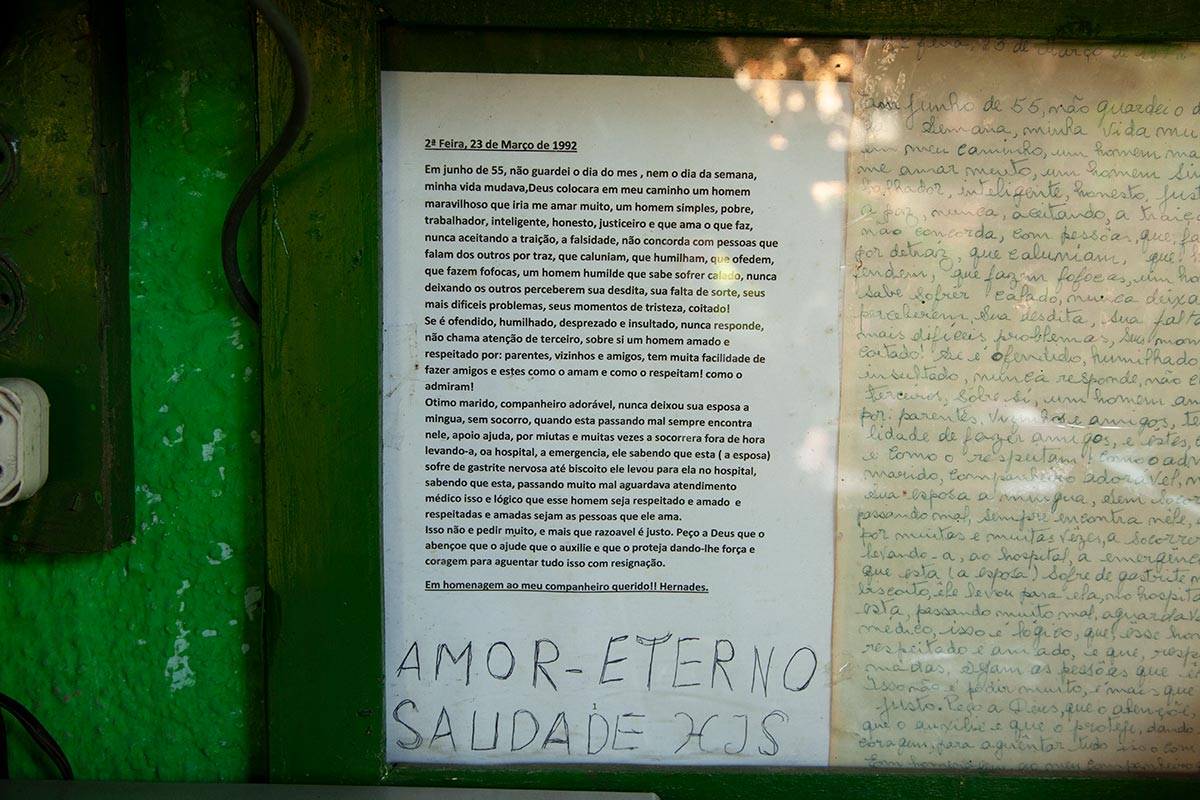

Working with CPMA, the Family in Transit program began with an experimental partnership with alternative penalties ordered by the Justice Court for a group of approximately 25 people who had lived a moment of crisis and vulnerability and were now hoping for restorative justice. As part of the collaboration between Núcleo-MAM and CPMA21 a special program of visits and dialogues were organized with the aim of exploring the meaning of the museum, collections, and collecting together with exercises for the production of new narratives and shared memories. It was in this context of conversations about memory, affections, and reliquaries in our lives that the group decided to visit Rancho Verde, following Seu Hernandes’ neighbor speaking about him, the Rancho, and a special love letter – a letter discovered by Seu Hernandes from his wife after her death that he often cited. The group visited the Rancho taking with us the pedagogical and therapeutic practice of the conversation circle. From that moment on HJS, his life of isolation, mourning, and loneliness were reconfigured and reborn. He integrated into the program and its agenda and the Rancho became one of the meeting places for the group.

The program continued until the Nucleus project ended in 2012. At the same time Ignes teamed up with Priscilla Grimberg (co-cordinator and co-founder of Casa Museu Rancho Verde) and together we inaugurated a more transdisciplinary approach, interconnecting practices of educational curating, social museology, and participatory poetics with those of sustainability, drawing attention to the socio-environmental context of Rancho Verde. We continued the conversation circle opening it up to the co-participation of new people and institutions, with a view to building a new cycle of terrestrial citizenship. With the action “Can a House become a Museum?”22 Rancho Verde began its metamorphosis to becoming Casa Museu [House Museum] that is today an award-winning local action in the city of Niterói (2019).

HJS – Seu Hernandes

Seu Hernandes was born in 1931 in Teresópolis – a rural town in the state of Rio de Janeiro. In 1942, at the age of 11, fascinated by the radio, he took a train to Rio de Janeiro to make his first dream come true: to get to know Rádio Nacional and what at the time was the country’s first radio soap opera, “Em busca da Felicidade” [In Search of Happiness] which was broadcast from a warehouse near his home. He fell in love with Rio de Janeiro at first sight, and a year later, at the age of 12 he took the train again to the city, but this time to stay permanently. When disembarking in the “cidade maravilhosa” [marvelous city – a well known moniker for the famous city] in a ritual of autobaptism, he asked for the blessing of the city so that it may adopt him as a son. It was in 1955, as he says, that his life would change forever when he met Dona Edinéia de Matos Silva, from Belo Horizonte, with he whom woud marry and live until she passed away in 2009. When she left after 56 years of a beautiful LOVE story, revered to this day by HJS through the living memory of her that he brings to his works, such as O berço da saudade [The Cradle of Longing] and so many others.

In his Mold Manifesto against rationalism in architecture, the Austrian artist and architect Hundertwasser radically states that, only the project in which the architect, the bricklayer, and the occupant form a unit can be called architecture, that is, when the same person integrates all three roles.23 This is the case of Seu Hernandes, who dreamed of, designed, and built his own house.

In the year 2000, after turning seventy and retiring from his job as a building janitor, where he had also lived for most of his life, he suddenly found himself homeless. So he found that he had to sell his only asset, an old Opal 1975, to buy a small piece of land in Morro do Bumba. Thus, according to him, the greatest task of his life began: the construction of his own house, when he had nothing.

Yet he managed to connect to the memories and simplicity of his childhood home, expressed in the model made by him during the self-taught construction process, building with few resources and using recycled materials. The land needed to be grounded and that was how he started the practice of collecting materials around the community, initially wood and tires, which were filled with sand. After two years of construction and seven years of living with his beloved, HJS found himself immersed in mourning, seeing no sense in anything, until one day he found a love letter to him, written by Dona Edineia, that although not delivered when she was alive, offered a balm, somehow making it possible for them to meet again.

Love, Art and Justice

It was precisely at this point in his life, in 2010, that we met Seu Hernandes, drawn to him by his neighbor describing the Rancho Verde, his collecting of things, his story of mourning, and in particular, the love letter. Reading and rereading the letter became vital for Seu Hernandes, especially when dealing with other people with whom he could share his pain, memories, longing, and his many life stories. It can be said that the meetings and conversation circles organized by the Family in Transit program and other initiatives of integrative community therapy, complemented the love letter, as a kind of magnet for a series of encounters that we would experience together for almost two years, inaugurating Rancho Verde as a collective and curative space that intertwined art and restorative justice.24

It is important to note that Brazil and the world have been discussing the need to avoid incarceration by investing in alternative penalties and measures to imprisonment. According to Rossana Xavier, CPMA social worker, alternative sentences are an opportunity for those who have committed minor crimes to avoid segregation and, at the same time, to get society involved in the subject’s (re) socialization process. It is believed that the period of compliance can be an opportunity to interrupt the cycle of violence, reduce judiciary measures as the sole means of conflict resolution, and demystify the practice of justice as one of punishment only. In addition to such alternative penalties, the CPMA program in Niterói introduced in a pioneering way an initiative called “Roda de Terapia Comunitária Integrativa” [Integrative Community Therapy Circle] a model hat was also adopted as a preventive health practice by the Ministry of Health, in the same year of 2010. The conversation circle approach with its focus on therapy without hierarchy, welcoming all participants equally, where everyone learns through the sharing of life experiences, contributed not only to the humanization of the alternative penal program proposed by CPMA, but also opened up an area of confluence for possible cultural citizenship, where art museums and other cultural contexts and workers could act as agents, offering restorative social practices and policies and fostering collaborations between public institutions of art, culture, and human rights.

Tragedies, Earth, Embryo

Earth and Tragedies

The socio-political and global context of the first decade of the 2000s promoted a willingness to reflect on so-called development models. The world debated “sustainable development” as a common and central theme of humanity.25 Twenty years after its insertion on the global agenda, the world environmental conference, RIO+20, held in 2012 named after the historic global meeting held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992,26 was key to mobilizing these discussions at the international, national, and local levels such as in Bumba, a favela in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Europe, for its part, having long begun to understand the generation and management of waste as an exemplary expression of the failed linear production-consumption-disposal model, started to promote a week of discussion and reflection aimed at changing predatory practices known as European Waste Reduction Week (EWWR).27 In Brazil, however, this issue was still in the Stone Age, given the lack of political guidelines and the attribution of waste management responsibilities, visible in the hordes of informal garbage collectors and scavengers and socio-environmental degradation.

In Niterói, municipal governments had demonstrated both pionnering and contradictory attitudes toward wase management and environmental concerns. On the one hand the city had been a pioneer in the country with respect to selective collection in the 1980s.28 On the other the municipality became a symbol of socio-environmental irresponsibility as evidenced in the tragedy that occurred in Morro do Bumba, a direct result of permissiveness and neglect with regard to the construction of favela settlements on top of former garbage dumps. In April 2010, the tragic landslide and explosion that occurred in Bumba left up to 60 houses buried and at least 46 people confirned dead with an estimated 150 missing residents – a further tragedy of hidden deaths, and countless others homeless.29

The devastation of those who experience a landslide such as that of Bumba may be paralleld with that of surviving a shipwreck, as in the harrowing description portrayed in Edgar Alan Poe’s short story “A Descent into the Maelström”:

We were now in the foam belt that always surrounds the maelstrom; and I thought, of course, that in an instant we would be engulfed by the abyss … It was like an immense wall writhing between us and the horizon.30

Deployed as a starting point for the work Tale as a Tool by the artists Aurélien Gamboni and Sandrine Teixido, the story is used as a tool for healing – paralleling feelings of the impending shipwreck and strategies of survival with environmental disasters and the preparation for contemporary climate challenges. First presented in Brazil at the 9th Bienal do Mercosul (2013), the artists, Sandrine in particular, became involved with our work at Bumba and lead community workshops six years after the tragedy.31 Tale as a Tool exemplifies a mode of working that organically and naturally articulates networks, enabling a metamorphosis, connecting micro actions with possibilities of unimagined scales.

The Embryo

The Bumba tragedy and the international debate surrounding outdated development models were important catalysts in promoting, at the beginning of the 21st century after a decade of discussion, the Brazilian regulatory framework for solid waste management.32 Around the same time, we met through our children, marking the embryo of this joint journey as one of many commonalities between the two of us, ranging from social work in favelas to our mutual desenchantment with society and its negative impacts. With solid waste as a primary interest, understood as one of the most dramatic aspects of the destructive linear production-consumption model, we had a starting point to think together about the need for urgent change toward practices embracing a new planetary consciousness.33 In addition to deciding on where to start, we intuitively sought, in our many conversations, how we were going to do it. In this sense, meeting with HJS at his Rancho Verde home in Bumba, illuminated the possibility of a dreamed metamorphosis, initially made tangible by that hidden life and dwelling. According to HJS, he re-encountered his flame of life in garbage, scraps, and objects from abandoned areas, each finding new form and expression recycled as a lamp or mug made out of reused paint.

Our long conversations tuned our dreams and utopias (of actions representing a terrestrial citizenship) with those of HJS (of sharing his life story, his inventions, and his interplanetary faith in the “system” with more people). Rancho Verde, which had been configuring itself since 2010 as a place of encounter, became no longer just an address, but, also, at that moment, an open space to think about and promote new worldviews – alternative designs based on critical and affective reflections and the reframing of practices from those of a fragmented toward a complex rationality. A place of learning and multiplication, anchored in care practices, embracing those who have suffered, turning their memories and pains towards love. Over time, bottles, flowers, old toys, and so many other creative series appeared. These were cataloged and arranged in installations, transforming a mere collection of things into an artistic reliquary.34

Over the years we have observed that the main asset of this sustainability laboratory, named Casa Museu Rancho Verde, is the e/affective relationship of this triad – casa, museu, rancho – marked, above all, by the synergy of affinities that continues to this day and that has become a network, an array of points of green light irradiating in several directions, as briefly described below.

Germinating, Flowering, Bearing Fruit: The Expansion of Knowledges and Practices

How to build a “community of destiny” that draws on the experience of everyday life? Striving to respond to this question, we organized the 1st Week of Waste Reduction in Niterói (SNRR), with the goal of: putting this issue on public agendas, to raise awareness, and to mainly engage the common citizen in these global discussions, similar to the European ones, with the mantra that the best waste is that which is not generated.

Promoted together with the European Union we organized three editions of the SNRR (2012 to 2015), effectively mobilizing a critical and informed approach with regards to the prodution of waste and facilitating a platform for actions and actors in the city working toward a new rationality.

The program was divided into two axes of activity:

1. Interventions, workshops, films, and debates with a socio-environmental focus, such as the Observatório da Varanda – MAC 360º [Museum of Contemporary Art, NIterói (MAC) 360º Veranda Observatory] addressing marine waste and pollution in Guanabara Bay.

2. Emphasis on local models and practices in favelas, with representatives of the 1st edition of Rancho Verde from Morro do Bumba, Maquinho [Community Art, Cultural and Technical Center] in the favela opposity MAC, Morro do Palácio and the Family Architect Project from Morro Vital Brazil.

When we included Rancho Verde in the agenda of the 1st SNRR, we had as a conviction, and at the same time a dream, that sharing the experience of the rebirth and resignification of garbage as lived by HJS could reveal other ways of doing, and, who knows, inspire more transitions to forms of complex rationality.

The years 2012 and 2016 were watersheds for us. Beginning with the establishment of our organization C3 (Collections, Collecting, and Collectives) Sustainable Actions and followed by subsequent repercussions for Rancho verde, both from the point of view of: (a) scale and scope of the practices of socio-environmental agencies, as well as (b) a curatorial selection of the emerging collection of HJS works. Both these modes of working began in 2012 and became key to the celebatory year of 2016, on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Niterói (MAC), when Rancho Verde/Seu Hernandes were invited to participate in the exhibition Guanabara Bay: Hidden Lives and Waters35 and we organized a series of fora on socio-environmental issues as part of the museum’s MAC Forum program, culminating with the launch of the international short film The Discarded36 timed for the context of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, and featuring an interview with HJS recorded at Rancho Verde.

This socio-environmental focus was defined at that time by the director of MAC, Guilherme Vergara, as a critical site-specific curatorial practice for the museum:

Culture, environment, and society come together [literally and metaphorically in the museum’s circular] form and [as a] symbol for the visitor’s appreciation.37

Our work on curating selections of Seu Hernandes’ works had started in 2012 with the question: “Can a house become a museum?” In turn leading us to reflect on the resignification of his wife’s love letter as the beginning of a collection and on the recognition of art in the daily creation of HJS. It was also a question for us with a view to experiencing the potential of the confluences between our worldviews and the exchanges between lives and knowledges that had been happening at Rancho Verde.38 This provocation triggered the construction of a living sculpture – an aesthetic, existential, and therapeutic reinvention of day-to-day living – as a key characteristic of this sustainability laboratory.39 In 2016, in presenting Rancho Verde/Seu Hernandes’s work at MAC, we had already embraced the Rancho Verde as a Casa Museu, as an irradiation project contributing to activist and artistic processes related to the environmental issues of Guanabara Bay and the city of Niterói. This understanding woult be further emphasized in our participation in subsequent exhibitions such as MADD (2017) and the Museu Bispo do Rosario Arte Contemporânea (2019).40

All these modes of working nurture and are nurtured by awareness and affection, as Cristiana Seixas notes, in her essay in this case study, linking the poems of HJS with those of the Brazilian poet Manoel de Barros.41

I returned several times … to make room to experience and learn another logic of reading and inhabiting the world.42

Casa Museu Rancho Verde Today: Care Practices and Metamorphoses

The last pre Covid pandemic events that took place in collaboration with and at the Casa Museu in 201943 celebrated municipal accolades – special awards44 and certification45 as a local cultural center – effectively integrating the Casa into the municipal network of local actions and the public school system. For us this was an illustration of how dreams can be realized and a demonstration of how efforts by multiple actors in collaboration can point toward a socio-cultural and environmental transition based on care and complexity.

Today the Casa Museu acts especially as:

A. Meeting point and place for experimentation working toward reconnecting and promoting terrestrial citizenship through new museological practices;

B. Sustainable practices model, making the Bumba project tangible, a possible reality that is accessible to all, by all.

In this way, the communities start to find micro-solutions instead of problems, where a seed of hope may be sown, making the Casa and its network “green” focal points, generating new e/affetive mutations and the awakening that another life may be possible.46

Taking Care of the Backyard

As a critical point of coherence between our actions and reflections on our practice, we have since the beginning been concerned with simultaneously promoting and continuing the legacy initiated by HJS (particularly with respect to the continuous supply of green paint)47 and with expanding the potential of the key environmental aspects of the Casa. In this regard, we focus our efforts on our own backyard. This included reducing our environmental impact and self-generating energy, fostering practices of better waste management, and the use of eco technologies, be it water heaters or in treating effluents.48

Some of these Casa initiatives are featured in two of the thirteen web TV episodes of the 21st Century Survival Manual.49

With particular attention to and care for the social dimension of these interventions, we adopted the basic principle of the transfer of knowledge and income in our focus on training and the hiring of local labor. Here, the goal was two-fold: to form local social agents as multipliers of eco-technologies and to support local suppliers and employment whether in providing meals for the workshops or in clearning or building services.

Additionally, any funds received through prizes, donations, and partnerships are used to preserve the heritage of the house and surrounding land.50 These range from construcing retaining slopes, renovating the roof, building a back wall, and creating a multipurpose space, which made it possible to show films and hold workshops and shows sheltered from the rain.51

The Uncertainties and the Possible Futures of a Micro “Community of Destiny”

In this brief overview, we have outlined some of the ways the Casa comes close to Morin’s notion of a micro “community of destiny” in its day-to-day operations and in its modeling and multiplication of everyday modes of working. The Casa’s success and what happened in Bumba seem fundamentally due to a shift from an individual and hidden experience to one of networks and community, bringing with it the potential of being an agent for metamorphosis.52 A key dimension here is the mutual affinity in the encounter between Seu Hernandes, the Casa, and the profile of the social agents involved and the ideas mobilizing collective action including: motivations and dispositions, shared stories and histories, empathies, and utopian hopes for other realities that allow human survival on Earth. Another vital element has been the effective articulation of networks, a process that has led to exemplary micro actions irradiating a “community of destiny” at the local, national, and international level. A final aspect, very particular to the birth and life of the Casa, drawing on the inspirationg behind the spirit of Rancho Verde, concerns the wise, loving, inventive, and welcoming figure that is our dear and unique partner, HJS,with whom we are honored to share this process and laboratory, and whose history we narrate here, an eleven year project that in 2021 now moves into full adolescence.53

In putting together this report of the germination and flowering of the Casa, we also reflected on the enormous difficulties of the ongoing management of this metamorphosis, due to both internal and external factors. The latter mainly involve: (1) violence and other problems, typical of a peripheral environment in Rio de Janeiro that compromise our security, the space itself, and that of visitors; (2) the establishment of a remunerated structure to maintain the activities of the Casa that has been running primarily on voluntary investment by its organizers and collaborators for more than a decade; and (3) the fact that the Casa is a private environment and home, whose owner is now approaching a century of life.

The challenges arising from the external environment are mainly related to the current moment of paradigm54 shifts and “polycrises,” still in the transition from a fragmented rationality to a complex rationality. These shifts are evident in the gaps between still emerging sustainable models of micro-resistence with current business strategies and capitalist world systems that limit the collaborative capactity of the Casa. Despite our drive to revise current models since the beginning of the process (be it the reuse of paint cans for HJS series of mugs and lamps or via waste management week workshops (SNRR) that we ran in 2012), it has only been in the second decade of the 21st century that we have begun to see companies examine their waste production proceses, as in for example the internalization of circular economy concepts in their actions. It is from the perspective of embracing complex rationalities that the Casa’s activities point the way forward, such as, for example, serving as a context for resignifying waste production via workshops and exhibitions in Bumba, or by organizing cooperatives and training, or even as an initial part of this chain by being a selective collection point, as in the case of partnerships with paint and material supply companies Akzonobel and Tetrapak.

However, all these difficulties do not hinder our dreams or the ocean of possibilities that we see unfolding at all times. Fueled by the love and hope that are renewed with every action and every encounter, there are many dreams that we still cherish. At the heart of this utopian project of metamorphosis is the expansion of the scale of education for local actors and the consequent expansion of their horizons and conditions, be it in the training for the implantation of new eco-technologies in the Casa (such as the still non-existent rainwater capture devices and those of photovoltaic energy), or in the training of teachers for sustainable practices.

However, the conduct of the current Brazilian federal government threatens the strengthening of partnerships and expansion of the Casa. The official response to the Covid-19 crisis had at first included an emergency income program. However the subsequent interruption of the program has caused great distress. Together with the dismantling of environmental and cultural policy, this has dealt additional challenges in the struggle to overcome structural inequalities and modes of valuing human beings who “have” over “being”55 especially in those of “subnormal clusters” such as the Morro do Bumba, the favela base of the Casa. However, from a more positive perspective, the municipal government of Niterói points to the possibility of expanding our actions following the Casa’s recent award (2019), such as being a space for the training of multipliers and students in collaboration with the city’s Secretaries of Education, Environment, and Culture, as well as the city’s private education network.

We also see future possibilities together with long-term community organizations, non-profits and civil partners, where, for example, we dream of establishing in Bumba: a music group (partnering with the social NGO Orquestra de cordas da Grota [String music group in the Grota favela]), and the formation of community ecoagents (IAM’s Ecomagente Project).

Documenting and preserving the work and life of HJS, particularly as he will soon be 100 years old, has been a very important and key challenge for the project. To share his wisdom and legacy, what we sow also needs to be perennial, a practice beyond being solely grounded in individuals. It is in this sense that the Casa can be seen as a public, living, timeless, and impersonal heritage for the use of the communities of Bumba and Niterói. This may take place either physically, in the continuation of the Casa as a place of hope and as part of the city’s socio-cultural offerings or virtually, via other formats, such as a Casa book comprising photos, details of our actions, texts by HJS and invited partners (a project we have long dreamed of doing). One such initiaive is a virtual museum-house tour, “Virtual Casa Museu Rancho Verde Virtual,” a new project that we have been working on, drawing on the Casa’s exponential potential to generate connections and dissolve geographical barriers to participation. We understand that by leveraging a specific location, we can impact its surroundings and beyond.

In a universe of so many unknowns and amidst present uncertainties, we are concerned about the future of the Casa Museu Rancho Verde as an agent of life and metamorphosis and a space for a micro “community of destiny.” We constantly ask ourselves: how to remain united, creative, and hopeful to face challenges projected for the post-pandemic world? How can we direct the Casa towards independence from our agency?

These questions resonate for us. They challenge but also pool our strengths. It is an endless struggle, where we are certain that there are more “hidden lives” and potential to be unveiled in other subtle layers of this story. In addition to HJS, the Casa Museu Rancho Verde project, the many encounters, and the practices developed over the past ten years, we would like to thank here some vital presences, without which we would not have this story to tell. According to family therapist Bert Hellinger56 everyone is part of a constellation. Exclusion and invisibility is what makes living systems sick, whether in the family or in society, and it is no different within a job. The act of recognizing strengthens the sense of belonging and the strength that each of us represents within the systems.

Our list of thanks begins by going back to the beginning of the beginning, to the genealogies that (co) inhabit this system, suggesting a constellation of hidden lives that came together at one momen in time and place: Guilherme Vergara and Jessica Gogan who believed and supported the fragile and uncertain initial ideas of the Family in Transit program; Rossana Xavier who agreed and made the partnership with CPMA feasible; our friend F. who connected us to Seu Hernandes; the HJS himself who opened his home and heart; Dona Edmeia, who left before leaving a love letter that would unite everything and everyone; and, finally, the creative force that united us (Priscilla Grimberg and Maria Ignes Albuquerque), and connected us to this virtuous and ascending flow of light and unimaginable collaboration.

The list extends to our web, composed of:

Museums, such as Bispo do Rosário, MADD and the MAC, Niterói, Environmental Action Art Program; Audiovisual producers such as Provisório Permanente, Amorim Filmes, Útero, Sound off films and Faz Digital; Universities, such as the UFF Extension Program – Museum Laboratories without Walls; NGOs such as Engineers Without Borders – RJ, Instituto Mesa, Casa Museu Eva Klabin, Instituto Ambiente em Movimento – IAM, Social Educar Project, Non Stop musical group, incubated by the Grota String Orchestra, Ponto Org, Makers Meal Project; Bem TV, Grael project; Companies such as Icarahy Canoa Clube, Solarize, Ampersand design, Brettas bike, AkzoNobel – Everything in color, Tetrapak; in addition to the Niterói municipal government, PRODUIS and its Culture Secretariat with the recent network of local actions. Among contemporary artists and activists from different fields, we have the collective Re Afrodite (Cyprus), Sandrine Teixido (France), Daniel Marques, Leandro Almeida, Marcia Campos, Agrade-se and Henrique Viviani, Diana Kolker, Maria Joâo, Robson Lemos, Josemias Moreira, Gustavo Stephan, Silvia Pires, Marcus Vinicius Fattor, Duda Mattar, Breno Platais, and Marcos Palmeiras,57 in addition to the local and primordial support of Henrique, Flavio, Seu Antônio and family, Felipe, and our dear Angelica.

This is an evolving list always open to new collaborations and developments – thanking everyone who supported this local planetary “do-in” and also launching a call for more magnets and love letters to be used as awakening devices for the sense of belonging, so necessary to overcome the current crisis in civilization. Belonging is the same as surviving, and since there is no individual destiny that can survive in isolation, we need to come together. As Sorokin says:

Love can provide a vital “social glue” to keep us together when facing challenges. If we split up, an evolutionary meltdown seems guaranteed. If we come together in an authentic way, however, we have the real potential to make an evolutionary leap. And, to unite, we need to reconcile the many differences that today divide us. We need to find harmony where today there is discord. We need to cultivate respect and consideration for others which, after all, is at the basis of love.58

***

For more information:

Casa Museu Rancho Verde

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Casa-Museu-Rancho-Verde-1780444935503933/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/casamuseur/

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCDoEY4C9ONpuYgSbgGIug7A

Priscila Grimberg

Designer, 50+, mother, curious and interested in everything that works toward bettering itself. She is a member of the Environmental Justice Laboratory at the Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF), the council of NGOs, and is co-founder of “Casa Museu Rancho Verde” and a metamorphosis enthusiast for a community of destiny, based on the broad scale collective action of societal actors as a way to make survival possible in the third millennium. She holds a masters in sustainable development and is a doctoral student in public policy, strategy and development both at Universidade Federal de Rio de Janerio (UFRJ). She has over fifteen years of experience working as a consultant fostering relationships between business and society, especially in extractive, infrastructural, and housing sectores in peripheries. She is specifically interested in the territorial approaches to development.

Maria Ignês Albuquerque

50+ mother of 4, pedagogue, and sustainability designer (Gaia Education), she has over twenty five years experience in art educational project and curatorships at: Museum of Contemporary Art in Niterói, Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro, and Oi Futuro) and internationallly at the Metropolitan Museun of Art in New York in their programs “Parent Child Workshop” and “Doing Art Together” in collaboration with the public school system in the city. She developed the Family in Transit program together with the Núcleo Experimental de Educação e Arte at MAM Rio. Over the past ten years she has been working on environmental issues as co-founder and manager of the Casa Museu Rancho Verde project. She is an artist / environmental activist with a focus on marine waste.

1 Johan Rockström. et al. Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society, v. 14, n. 2, p. 32. 2009.

2 PRATES, IRVING, 2015, p. 30

3 Edgar Morin and Anne-Brigitte Kern, TERRA-PÁTRIA (Porto Alegre: Editora Sulina, 2003).

4 Serviço Social do Comércio, Para um pensamento do sul: diálogos com Edgar Morin (Rio de Janeiro: SESC – National Department, 2011).

5 Ricardo Abramovay, Muito além da economia verde (São Paulo: Editora Abril, 2012).

6 Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Una Epistemología del Sur. La reinvención del conocimiento y la emancipación social (Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores, CLACSO, 2009). P. 160-209.

7 Enrique Leff, Epistemologia ambiental.5th Ed. Tradução de Sandra Valenzuela (São Paulo: Cortez, 2010), pp. 23-108

8 In Thomas Kuhn’s view, science is made up of paradigms – accepted model or standard. Thomas Kuhn, A Estrutura das revoluções científicas. 5th ed (São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva, 1970).

9 Edgar Morin, Os sete saberes necessários à educação do futuro. 2nd ed (Brasília, DF: UNESCO, 2000).

10 See more at: Edgar Morin, Introdução ao Pensamento Complexo (Lisbon, Piaget Institute, 1991).

11 Edgar Morin and Anne-Brigitte Kern, TERRA-PÂTRIA, p.178

12 Edgar Morin, Os sete saberes necessários à educação do futuro.

13 Marta de Azevedo Irving, Sustentabilidade e O Futuro que não queremos: polissemias,controvérsias e a construção de sociedades sustentáveis.Dossie Sustentabilidade, Rio de Janeiro, no. vol. 9 n.26 ed. Soc signs, p. 1–4, 2014. https://doi.org/10.15713/ins.mmj.3.

14 Marta de Azevedo Irving and Elizabeth Oliveira, Sustentabilidade e Transformação Social (Rio de Janeiro: SENAC Nacional, 2012).

15 Edgar Morin. Target community. (…) “We need to base human solidarity no longer on an illusory earthly salvation, but on the awareness … of our belonging to the common complex woven by the planetary era, on the awareness of our common problems of life or death, on the awareness of the agony situation from our beginning of the millennium In. Edgar Morin and Anne-Brigitte Kern, TERRA-PÂTRIA, p. 179

16 The five skins: 1 Epidermis; 2 Clothes; 3 House; 4 Identity, Family, Nature, Country, Other People; 5 Earth, Ecology, Nature in Pierre Restany, The Power of Art Hundertwasser: The Painter-King with the Five skins (Cologne: Taschen, 1998), pp. 10-11

17 Seu Hernandes had different references to that voice. The System as its own thought, at other times as the voice of God or angels. Depending on the narrative, he alternates or merges these perspectives in his recounting.

18 Sidarta Ribeiro in Bruna Vargas and Sidarta Ribeiro, If people don’t dream, they don’t see a future, MENTAL HEALTH, 2020. Available at https://gauchazh.clicrbs.com.br/saude/vida/noticia/2020/07/sidarta-ribeiro-if-people-don’t-dream-don’t-see-future-ckcqd85v4001o013gx3n50nnf.html (Accessed March 2021)

19 We maintained the anonymity of the HJS neighbor, respecting the CPMA secrecy code.

20 MAM, blogspot. Despedida: O Núcleo Experimental de Educação e Arte, 2017. Available at https://nucleoexperimental.wordpress.com/ (Accessed March 2021)

21 After a 3-year cycle (2009 to 2012), the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro ended its work and efforts that explored and reflected the search for new possibilities and meanings of art museums for education in the 21st century.

22 Detailed later in this document.

23 Wieland Schmied, For a More Human Architecture in Harmony with Nature (German, Hardcove. 1997)

24 Milene Zanoni da Silva, Adalberto de Paula Barreto, Josefa Emilia Lopes Ruiz, Silvana Philippi Camboim, Rolando Lazarte and Maria de Oliveira Ferreira Filha, O cenário da Terapia Comunitária Integrativa no Brasil: história, panorama e perspectivas. Temas em Educação e Saúde, [S. l.], v. 16, n. esp.1, p. 341–359, 2020. DOI: 10.26673 / tes.v16iesp.1.14316. Available at: https://periodicos.fclar.unesp.br/tes/article/view/14316. Accessed on: 8 mar. 2021

25 From member nations of the United Nations (UN)

26 The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, known as RIO + 20.

27 See more at EWWR, European Week for Waste Reduction. Available at: https://ewwr.eu/project/ (Accessed March 2021)

28 The first systematic and documented Brazilian experience of selective collection started in April 1985 in the neighborhood of São Francisco, in Niterói (RJ) with professor Emilio Eigenheer from UFF.

29 See more in Morro do Bumba: sad symbol of the garbage problem, (Revista em discussão, 2010), Available at, https://www.senado.gov.br/noticias/Jornal/emdiscussao/revista-em-discussao-edicao-junho-2010/news/morro-do-bumba-triste-simbolo-do-trash-problem.aspx (Accessed March 2021)

30 Edgar Allan Poe, Contos de imaginação e mistério (Tordesillas; 1st edition, 2012), p. 111.

31 Sandrine Teixedo “A short story as a tool” MESA Magazine no.6 “Hidden Lives”

32 Through the National Solid Waste Policy (PNRS) – Lawnº 12,305 / 2010

33 Edgar Morin and Anne-Brigitte Kern, TERRA-PÂTRIA.

34 A lot of HJS texts started to be written at the time and today, there is a profusion of them, subject for a dreamed-of future publication.

35 Cultura Niterói, Guanabara Bay, Waters and Hidden Lives, 2012. Available at: http://culturaniteroi.com.br/blog/index.php?id=2294&equ=macniteroi (Accessed in January 2021)

36 Annie Costner and Carla Dauden (directors) The Discarded, 2016. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rb23MGDsQ2c&feature=player_embedded

37 Guilherme Vergara in: Maria Inês Albuquerque e Priscilla Grimberg, “Como nasce uma idéia?” (Report of the 1st Niteroi Waste Reduction Week, 2013), p.3

38 Leandro Almeida, Como nasce uma experiência (2016). Available at https://youtu.be/dDKMFtG_lBg (Accessed March 2021)

39 In the dimensions of care for the individual and the planet and as a metamorphosis, understood as a change in consciousness and behavior In Serviço Social do Comércio, Para um pensamento do sul: diálogos com Edgar Morin (Rio de Janeiro: SESC – National Department, 2011).

40 Bruno Alves, Casa-Museu Rancho Verde integra exposição no Museu Bispo do Rosário (2019). Available at https://brunoeduardoalvesmultijornalista.blogspot.com/2019/09/casa-museu-rancho-verde-integra.html (Accessed in March 2021)

41 Psychologist, bibliotherapist, specialist in art therapy

42 Cris Seixas “Poetics of Rescue” Revista MESA no.6 “Hidden Lives” 2021

43 GOVSERV Niterói, Casa Museu promove tarde especial na próxima sexta-feira (04), no Morro do Bumba! (2019). Available at: https://www.govserv.org/BR/Niter%C3%B3i/2139912266147347/Cultura-Viva-Niter%C3%B3i#location (Accessed March 2021)

44 Daniela Kalicheski, Ações de trabalho voluntário em Niterói ganham prêmio de apoio à cultura (Jornal O GLOBO, 2019). Available at https://oglobo.globo.com/rio/bairros/acoes-de-trabalho-voluntario-em-niteroi -with-culture-support-prize-23609725 (Accessed March 2021)

45 As a Ponto de cultura [Culture Point a network of cultural and community centers drawing on Gil’s idea of “do-in” points of culture.

46 Lívia Neder, Em Niterói, projetos locais promovem a defesa do meio ambiente:Atitudes simples promovem o despertar da consciência ecológica e são exemplos positivos para esta e futuras gerações adotarem boas práticas sustentáveis (O GLOBO, 2019). Available at: https://oglobo.globo.com/rio/bairros/em-niteroi-projetos-locais-promovem-defesa-do-meio-ambiente-23710754. (Accessed March 2021)

47 Fruit of partnership with Akzo Nobel.

48 With reuse of workshop materials, selective collection and composting). See more at: Jay Marinus Nalini van Amstel, Oficina de Compostagem (Blogspot Ecomagente, 2017). Available at http://ecomagentegrota.blogspot.com/2017/10/visita-tecnica.html?m=1 (Accessed in March 2021)

49 Manual de Sobrevivência para o Século XX, Episode 10, 2018. Available at https://youtu.be/zVCRtXzvPWk (11:40 minute) (Accessed March 2021)

50 SOLARIZE, Doação da Solarize na campanha para reforma do telhado da Casa Museu Rancho Verde (2020). Available at https://www.solarize.com.br/site-content/11-blog/435-doacao-da-solarize-na-campania-for-renovation-of-the-roof-of-the-house-museum-green-ranch (Accessed in March 2021)

51 Leonardo Sodré, Grupo se mobiliza para reformar museu de artista popular no Morro do Bumba, em Niterói (O Globo, 2020). Available at https://oglobo.globo.com/rio/bairros/grupo-se-mobiliza-para-reformar-museu- de-popular-artist-on-the-hill-of-bumba-in-niteroi-1-24788053 (Accessed March 2021)

52 Edgar Morin and Anne-Brigitte Kern, TERRA-PÁTRIA.

53 Leandro Almeida (dir) Documentary feature film about the life of Mr Hernandes in the process represented in this edition as a photo essay. http://institutomesa.org/revistamesa/edicoes/6/portfolio/leandro-almeida/?lang=en

54 See more in Arilson Favareto, Multiescalaridade e multidimensionalidade nas políticas e nos processos de desenvolvimento territorial – acelerar a transição de paradigmas. Desenvolvimento Regional: Processos, Políticas e Transformações Territoriais. (São Carlos: Pedro & João Editores, 2020).

55 Marta de Azevedo Irving, Sustentabilidade e O futuro que não queremos: polissemias, controvérsias e a construção de sociedades sustentáveis(Sinais Sociais, Rio de Janeiro, vol. 9, no. 26, p. 11–36, 2014). p.15

56 Bert Hellinger and Gabriele Ten Hövel, Constelações Familiares – O Reconhecimento das Ordens do Amor (Cultrix, Brazil.2001) p.59

57 Casa Museu Rancho Verde, Ei, você! Sua presença é bem vinda! Junte se a nós também! (2016). Available at: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1807775302770896 (Accessed March 2021)

58 Pitirim Sorokin (1967) apud Maddy Hasrland and Wiilian Keepin, A canção da terra: Uma visão de mundo científica e espiritual (Rio de Janeiro, Roça Nova, 2016) p. 210.