On the Fringe: Art, Community, and Healing on Achill Island, Ireland

Dialogue with Doutsje Nauta, Willem Van Goor and Revd Val Rogers

Yet when I arrive at the far side of the island

And peer down at the outport on the rocks below,

The Atlantic Ocean rearing raw white knuckles,

Although I am globally sad I am locally glad

To be about to drive down that corkscrew road.

Paul Durcan, “The Far Side of the Island”1

Dutch artist Willem van Goor and his wife Doutsje Nauta emigrated from the Netherlands with their daughter to Achill Island in 1997, buying Bleanáskill lodge, a one-story home with three acres of gardens situated on the island’s dramatically beautiful Atlantic Drive. Remote and isolated, off Ireland’s west coast, Achill’s rugged and barren landscape is prey to the winds and salty air of the far-reaching edges of the Atlantic Ocean. Yet its dramatic setting, wilderness light, and spectacular skies have drawn many an artist and writer to its shores including the American painter Robert Henri (1865-1929) and writer Graham Green (1904-1991), German author Heinrich Böl (1917-1985), the painter Camille Souter (1929- ) and more recently Irish poet Paul Durcan.2 Despite the inordinate challenges of the island’s fierce weather conditions, various Bleanáskill lodge owners, over its hundred-year history, in particular the artist/writer Alexander Williams at the turn of the 20th century, challenged the wilds and strove to establish a sheltered tree grove and garden. Van Goor and Nauta more than continued this tradition, transforming the lodge’s acres into Achill’s Secret Garden, restoratively integrating sculptures, diverse plant species, and vegetable and herb gardens with surviving trees and shrubs, in parallel with various curative community initiatives.

One initiative in particular, created in collaboration with Revd Val Rogers featured a reconciliation interdenominational faith Service at St. Thomas Church, Dugort, on the island’s far north. Born out of the Protestant Achill Mission’s concern for the backwardness and poverty on the island in the 1830s, St. Thomas Church, finally completed in 1855, was part of a settlement that included a medical clinic, orphanage, schools, housing, and several churches. Presided over by the contentious figure of Revd Edward Nangle from 1833 – 1851 and spanning the years of the Great Famine, the missions’ evangelical zeal was a counterpoint, not without irony, to the very “impoverishment due in large part to the colonial policies of a Protestant ascendancy.”3 The mission’s fervor also ran up against an intransigent opposition of the Catholic Church where Archbishop John McHale decried the mission with the damning phrase: “There is no place outside of Hell which more enrages the Almighty than the Protestant colony.”4 Telling the mission’s story means revisiting the history of conflict between Protestants and Catholics in Ireland, one that is long and painful, entrenched in colonial politics, poverty, fights against British rule, and civil war. Held on September 24th, 2011, the service featured interfaith readings, music played by Van Goor on St. Thomas Church organ, and a commemoration of unmarked graves of both Catholics and Protestants buried in the church grounds.

The following dialogue is excerpted from conversations held at Bleanáskill lodge in July 2017 updated for this publication and interspersed with images of Achill Island, the interfaith service, visual essays of Van Goor’s artwork, and the couple’s Secret Garden.

Editors – Jessica Gogan e Luiz Guilherme Vergara

Reconciliation Service

Willem Van Goor – The story of St Thomas Church starts before Nangle. Why did he come to Achill Island? There was a reason. He got millions at the time from the United States and England, all invested in this settlement in Dugort, in the northern part of the island. At the beginning of the 1800s, amongst Protestant clergy in Great Britain, there was a wave of interest and newfound awareness focused on missionary work inside their own worlds. Instead of Africa and other far-flung countries they went in search of hidden pockets in their own country and there were many of them. Under British rule at the time, Ireland was one of them, especially in the West, and Nangle was part of this movement. A son of minor aristocracy that a generation further back had been Roman Catholic, he was a fanatical evangelical protestant. He visited the island and fell in love with two things – the landscape, which he found stunning, and the social cause. There were 8000 – 9000 living here in terrible poverty and horrible circumstances with no schools, no churches, and no hospitals. A series of small famines had already devastated the island even before what would be the big famine in 1848. There was nothing here. Just rocks, bog, seaweed… The people here had to eke out a life for themselves. Such survival instincts are core to the DNA of this population…

Doutsje Nauta – It’s still present, you can still feel it; a kind of anarchism that people really carry within themselves. Here people learned to do things their own way; it’s ingrained. For a long time they were not looked after. There was no reason to trust any authority whether church or government. You can only rely on each other, your family. Nothing more Irish than knowing who is your second cousin once removed…

Willem – You have to know who your relations are, because they are family and you can count on them. I spoke to a lady who told me that in a particular graveyard on the island that there are 36 headstones of 36 different families on the island all related to her. So when you count all the offspring together you’re talking about a small town and you were safe within that framework.

Doutsje – This doesn’t mean that it’s insular. For example, it’s really interesting to note, something I read recently, that 95% of the children going to school here end up going to university or college. I mean 95%! It’s amazing.

Willem – The Dutch photographer Con Mönnich came here in 1974 and shot in the region of 150 photographs of Achill Island. Then almost 40 years later when sifting through his stuff he found all these negatives, so he decided to come here again and see if anyone was interested in them. The photos have been presented in a number of exhibitions and soon will go on view at the National Museum of Country Life in Castlebar. In the photos you see both an Achill that has not changed and one that has changed drastically. Interestingly, there is one photograph, taken on the road out in front of our garden depicting 7 boys. According to a neighbor five of them are now multimillionaires living in England, USA, and Dublin, all from this little bunch.

Many of the big houses built here in recent years belong to people like them. This is just one story to show the enormous potential of the brains and entrepreneurial spirit on the island and of course, will power. I don’t know if this is only specific to Achill but I think in all those places on the fringe you find this spirit – people who had to flee from oppression and survive.

Doutsje – Survival and spirituality – however that is understood in different times – are deeply interwoven. I’ve heard many stories at our small table gatherings. For example, my friend Maebh O’Herlihy, formerly Roman Catholic, now studying for Church of Ireland [Anglican] ordination and of wide sympathy for all honest searching and spiritualities, speaks of family histories of hiding the statue of 5th– 6th century St Gobnait in the time of Oliver Cromwell’s brutal 16th century invasion of Ireland. Named after one of the Celtic goddesses, Gobnait was connected to many trade and craft people who asked for her protection as well as fishermen, miners, beekeepers, and farmers. Recently the small parish of St.Thomas’ Church bought Nangle’s old schoolhouse in Dugort, aimed at interfaith spirituality of all sorts, which will be hosted by Maebh, who is strongly embedded in Celtic spirituality. Such stories have come to the fore via ecumenical work on the island and particularly led by those residents (actual and former) that seek to reconnect to Celtic histories of the land and spirituality, like Maebh and previously Anne Tyrrell (who moved to midlands years ago).

Willem – There’s so much history here and many stories to tell. Returning to Nangle and the Achill Mission, they bought a piece of land in Dugort and started what was called the Colony. This included the first school in the West of Ireland for ordinary folk, a mill, printing press (The Achill Herald and Missionary Times), post office, coast guard, bakery, orphanage for girls and boys, clinic, and agricultural school. Most of the buildings are still there. It feels like some kind of small English village. There’s even a village clock. It was quite exceptional. The Mission acquired large land holdings and employed those who were starving. They built roads throughout the island and also the buildings of the Colony itself. A bleak, dark, and empty landscape was wholly changed. Facing starvation many became Protestant because they could get sustenance there. The Protestant Revd Nangle was present and providing for the community, while the Catholic priest was living in Newport, a two-day ride on horseback.

So the presiding Catholic Archbishop, John McHale of Tuam, became very angry as he saw part of his congregation becoming Protestant and an aggressive theological debate and vicious verbal attack ensued between Nangle and him.

There’s a telling phrase from the time of the famine that reflects this Protestant-Catholic conflict. People who turned to the Protestant missionaries for food and help were said to “Take the soup.” You would go to hell if you took the soup according to the Bishop. Although others say that people were welcome to come in and take the soup. Nevertheless terms such as “souper” – the one who provided food for the hungry in exchange for church adherence [or allegedly did so] – and “jumper”, one who switched denomination like some kind of traitor, or accepted help or employment from the Mission, were used – and in some case still are – to describe people in a pejorative manner.

While things have certainly changed, even when we first arrived here and hosted a party for my birthday people said, “Willem you can’t have all those people in the same room.” That was 1999. Only through our innocence! It was suggested that they didn’t get along at all. Yet there was singing and clapping! Like an American friend who in Belfast set up the Meals for Peace program that brought Protestant and Catholic youth together, it is possible to bring people together – music and food are good ways to do that.

I first got to know St. Thomas Church through a visit of a family member who is a scholar in early Christian literature and liturgy. Shortly after we moved here, he visited and we went around the island visiting churches. I remember him saying, “What’s that one over there? Let’s have a look.” It was open and we went in.

There was a harmonium there and I opened it and started to play. It had been built in Rotterdam and was more than a century old. Woodworm was creeping in all over but unbelievably it was still in tune. So I offered my services saying that I could play the harmonium instead of them having to listen to a tape recorder. They were very enthusiastic and from that day on I played every Sunday. I remember my uncle and grandfather played the organ every day for 70 years in the same church in the Netherlands. Suddenly I realized I was an organist and keeping the tradition going. Coming from the Netherlands I had not gotten involved in the Church of Ireland till that point. But when you go to a church and keep going they consider you to be part of it. You are seen as a member.

In addition to the harmonium, we were also able to acquire a pipe organ. One that was originally purposely built for a church in Newport and then lovingly restored by a former Bishop. When he had to move to England he sent an email around to the diocesan network asking: “Is there anybody interested in my pipe organ?”

I responded right away: “Did you ever consider Achill?” So we got the pipe organ free as long as we could assume the costs of removing it from his location in Crossmolina. The only thing we had to do was to find an organ builder who could take it apart and reinstall it. There are now only 7 organ builders in the country. The cost was 2800 euro. We did a fundraiser. Catholics and Protestants alike chipped in. This church is part of island heritage, also for Catholics. People said: “Whatever you need, whether a roof or an organ we will support it.” Authenticity, quality, and craft, their investment was palpable, understanding craft as a fundamental sense of gift. Music creates and motivates a common goal and brings people together.

This possibility was what inspired the reconciliation service. After Nangle there were three Protestant churches on the island – Inisbiggle, Achill Sound, and Dugort – the latter the only one still in operation. This means that even though the former churches may not be in use for religious services, their graveyards nevertheless still need tending. So St Thomas’ congregation shares responsibility to maintain them. One time I was visiting the overgrown Achill Sound graveyard with Tim [Stevenson], our Church Warden and I remember him saying:

You see all those little hillocks. They are all graves. They are in the hundreds and there are no records. They date back to the famine. Given the circumstances nobody knows if they considered themselves as Protestants or not, and as Roman Catholics can only be buried in a sacredly ordained Catholic graveyard, it’s very possible that many of them are buried in the wrong place.

We spoke about the unease related to this and the history of Nangle on the island and we thought that it might be a good idea to offer those buried a prayer service led by both a Catholic priest and Protestant minister. So we approached our minister, Revd Val Rogers, who both recognized that it would be too big an event for him alone and the opportunity of creating a larger event and he suggested approaching our Bishop, who in turn involved the Roman Catholic Bishops. On the day we had 250 people in the church with 30 priests at the altar, people from the island and various official representatives including from the office of the President of Ireland and police forces. Both Bishops addressed the congregation and then after that we placed 1000 wooden crosses on the graves. In that moment, I felt that that little tiny congregation had landed in the community after all those years.

Doutsje – St. Thomas Church seems to be able to facilitate these connections. Yet, in its position facing the wildness of the landscape, on the fringe of the island and the larger community, it is also always on the edge of just disappearing, so maybe what intrigues is also this struggle, an authenticity that captivates and makes things possible.

Willem – Where else would you be able to find a church that, when you are playing the organ, you can see the waves. The church gave me a kind of framework, one that enables you to adapt, but also, provides structure. Through it I was brought back into the fold of my beliefs. Church, religion, music were so much part of my life growing up. This didn’t happen because of the words of a preacher, but because I was playing the organ there. St Thomas Church has become very important to me in my personal spiritual life, because of the church itself, not any particular teachings.

Revd Val Rogers – It’s so interesting to hear Willem tell the story. I’d love to claim some credit for the interfaith service but I can’t, the instinct was already positive and strong in this tiny congregation to put crosses on unmarked graves in the church graveyard. They were confident that in a less belligerent time than the mid 19th these people would have been buried in Catholic cemeteries had the times not been so aggressive.

Willem mentioned earlier that the relationship between the Catholic Archbishop of Tuam, John McHale and Nangle was deeply polarized at the time. Like Nangle, McHale was a man of strong opinions, bluntly expressed. He resisted the establishment of primary schools in his diocese and province for many years. Education, he thought, would only give people notions. But Nangle wanted schools so that the people could read the scriptures – not hidden or corrupted by clergy – and no effort was spared to make people literate. To counter Nangle’s Protestant influence, McHale at last sent a Catholic priest to the island and set up a Catholic primary school there.

Those who came to Nangle’s church, whether out of conviction or because their children were hungry, or who took employment from him, all seemed to be lumped together as people to be shunned by the Catholic clergy. So it was certain that there were people buried in our churchyard who ought to have had a Catholic burial. We had a list of all the names of those probably buried there but no exact sense of who was in what grave. And it was Willem, Doutsje, Tim and Dorrie [Darlington – Church Secretary] who came up with the idea of a Service that would show love and respect and be a token of prayer and recognition of the lives of those unmarked graves in their existence past and present. I had not long arrived to preside over the parishes in the region at the time and I just ran with it another little distance and said, look, we must make a bigger deal of this.

In Achill you step into history up to your armpits and into a bog hole at any tick of the clock. It seemed past time to get our Catholic and Anglican/Protestant Bishops together with all the islanders, and to be indiscriminate in expression of love, and of regret for past belligerence. So we gathered a fine crowd, and spoke and prayed within the church building and out in the churchyard among the remains of the dead. There were reckless, generous, healing hugs and handshakes for friend and foe.

In worthwhile Services, in all helpful ritual, things happen in the psyche and the spirit that are change-making and, please God, encouraging and healing. It’s one of the major purposes of church life. From the leader’s point of view, the simplest gesture or word of love, formal or informal, facilitates the magic, the graced development of persons. It’s not just the robe or the stole, but the way you wear your heart and your body, and what they say and do. It invites people to step forward within or from their present reality into, please God, richer reality to allow themselves to be loved, to allow themselves to love each other and to let their guard down, and become more whole together thereby. I think that is very much what all of the rituals of the Church are about. All the decorations of the Church should be about the same thing – the physical artworks, the configuration of the building, the robes or whatever of the person up the front. All should be working to that end, to help people grow more real, mature, compassionate, and affectionate toward themselves and one another. And I think you could see and feel the healing happening on that particular day. I was grateful that it was so well attended and worked so well.

Trust, courage, humility, and self-knowledge are required while we do these things. Far from having all the answers I am living the questions myself. Those that were there that day came from many different perspectives. Forced by poverty to frequently become migrants, Achill islanders nevertheless maintained a love of home. There’s a history of a people embracing worldly experience, broadmindedness, but also, being down to earth. Like Robert Grave’s honest housewife, they have “a nose for fish and an eye for apples.” Worldly but also very practical and realistic, many made the most of themselves far beyond any of these old prejudices. Education was and continues to be valued both as key to making a living but also vital for their being and there’s a strong love of the humanities, music, and art. I wouldn’t expect any Achill person to become a cog in a technological machine. So when we pray, we pray in union with the faith, hope, love, and longing of all men. It is crucial that this speaks to a broadened sense of a Christian community, not always with happy, explicit or clear-edged faith but also in deep need or unknowing. Such space for each other brings us onto common ground in faith, trust, and love.

I was absorbed in these issues as I put the service together. I borrowed and adapted shamelessly from the Church of Ireland and Irish Catholic prayer books as well as other sources. I composed several of the prayers of the formal address. They had to be just right; I polished and polished them. It had to venture onto what might be painful ground for some of the descendants present, and it had to be somewhat conservative in its outlines because there is great respect for the better sides of established order here as there is great disrespect for established order that is oppressive or moribund. It was a process of discovery.

I love some phrases, one from Picasso, at least I think it’s from him, “If you know exactly what you are going to do, what’s the point of doing it”, and the other from Dorothy Parker, “How can I know what I think till I hear what I say”. Sometimes things happen in the moment, the right word happens in the moment, the clarification of issues and process and the ability to articulate it can happen in the moment. I deeply appreciate the general structure of the set rituals as well and I would not have the emotional energy to be doing fresh things every time. I have been a priest for 45 years and I don’t know how many Eucharists I have celebrated. Yet you hope it’s new every time even though you don’t change a word of it. So the Eucharist leads me as much as I lead the Eucharist, and the same for morning and evening prayer. It is a fresh event every time. Now if I were still a Roman Catholic priest, I might not be able to say that to you; ordained 45 years I might have run out of steam. But I am lucky in that I only have two to three Eucharists a week as compared to a Catholic Priest in this country who may have to say mass everyday, and two or three times over a weekend. Maybe my psyche has space and time to come fresh to the Eucharist so that it remains astonishing to me still. I am nourished and I hope to nourish my brothers and sisters. It is a vibrant event every time, emotionally and psychically. A particular joy for us in this impossibly tiny Dugort congregation is that we have Willem, a fabulous musician from whom glory pours out. He surely channels his ancestors.

Being on the Fringe: Bridging, Barges, Hospitality, and Gardens

Willem – “Being on the fringe” is a phrase I use to describe my interests and what has moved me – literally and metaphorically. There’s escapism, yes, I wanted to be away from the big city, the continent. Before living here, we were part of a community of over 400 households that lived on barges and houseboats in the Netherlands. Doutsje loved city life; I didn’t very much. I am more into nature. But I love to be with other people. Because we had a certain intimate knowledge of the law, we were asked to become representatives for the “floating community” in dealing with the government.

Doutsje – I was able to advise them on strategies. It had been my profession to organize communities to work toward changes to better their lives. I coordinated and developed social work initiatives including working with church organizations, running community centers, and developing and implementing police force sensitivity training. I had also organized conferences on local and national levels and knew people (nowadays called influencers) in local government. But at the time I had a full time job so Willem was more involved, I was only able to support/ facilitate when necessary.

Willem – Along with a few others we assumed the responsibility to represent the group’s voices and opinions to the authorities and point out wrongdoings and unconstitutionalism. It was all over the newspapers. Prior to that those that lived on barges and houseboats were seen as backward, illicit, and untouchable, on the fringe in the most negative sense. We tried to change that and very quickly public opinion was with us.

I had been living on the fringe in this way since leaving home and going to art school, on a small houseboat that was 10 meters long 3.5 meters wide, a house floating in the harbor with many other ships. People looked down on those who lived there. I had come from a very protected background. I remember my father came to visit me and he told me that the taxi driver when he asked to bring him to the harbor said: “Are you sure you want to go there?” He didn’t want to bring him there. My father was a very tall and elegant gentleman, he wore a suit and tie, and a hat and on the day he arrived it was washing day on the dyke. I can still see it! There were blankets, sheets, everywhere! [Laughing]

But to live there brought closeness and a sense of shared experience and you got to really know your neighbours. All kinds of people, from all walks of life; wonderful people on the fringe, so I love the fringe, and still do. You can draw on what’s best of both sides of a border and build a bridge between worlds.

Doutsje – To bridge has never been a goal but looking back at our lives we have done it a lot, we have connected different classes, different religions, different political parties, it just happens, it’s a kind of thread of our lives…

This also informs our work with “Wwoofers,” mostly young people who come to live and volunteer with us in the summer as part of the World Wide Opportunities Organic Farming network (Wwoof).5 They come here from far and wide in search of meaning, a broader experience, perhaps adventure. Often the people who come to us are at an important turning point in their lives. They too seem to be on the edge of something. We respond to this to the best of our knowledge.

Living, working, and talking with these young people greatly enrich our lives. We mainly do the latter during meals, around the table. The table is a symbol of togetherness.

Willem – The most important thing is the table, it is where you meet and eat, and sometimes it is extremely tiring and I wish I was under the table!

Doutsje – Here in Achill we find ourselves connecting all the time – everyone from the Wwoofers, garden visitors, those that stay in the Bed and Breakfast that we run in the house, the community…

Willem – When we came to live here I wanted to have a garden. But we didn’t have money to sustain it, so we opened up the garden to visitors. It was the same with our B&B. It was not my idea. I didn’t want it but I began to see the pleasure in giving people the opportunity to experience the house and garden. Hospitality has become about the simple things, cleaning the dishes, doing the floor, making the bed…

The landscape here is very harsh indeed, but being confronted by its beauty, it opens up possibilities that you never dreamed of being possible or even likeable. So, I find you are able to overcome and even cherish these challenges. When you go out on the fringe you find that there are so many other people living on the fringe and that there are all kinds of possibilities that you never thought of. Many people here escaped from somewhere…

Guilherme Vergara – The metaphor to go to the fringe, is about meeting the other…

Doutsje – Yes but living on the fringe also demands a different kind of survival. It’s not easy. Among other things we tried running a plant and shrub nursery. I have cooked and baked homemade goods to sale at a local market. Nothing made enough money. Willem said he didn’t want all these strangers in the house. But we got to the point that to run a B&B was the only possibility left, so I said well it’s either we sell or open the place up as a B&B.

Jessica Gogan – This question of survival and how to stay true to the fringe spirit is key. There’s an apt passage in the American naturalist and philosopher Henry David Thoreau’s classic book Walden, based on his experience of living isolated in a cabin in the wilderness for several years in the 19th century, where he talks about how the means of survival such as making baskets out of weeds are often turned into supposedly lucrative proposals. For him the challenge was how not to sell the baskets.6

Doutsje – I think the key word is love. Being on the fringe is making baskets, primarily meeting the other, “bridging,” and connecting. The only way you can do it is by love. How do we get more in touch with our humanity whether through simple tasks of hospitality or community work? Being open is key as is being without prejudice. For example, our daughter is gay, she was going to school in Castlebar when she came out and it was very revolutionary at the time. I attended a conference organized by the church and there were small groups of people talking about the topic. In one group I listened to a terribly worried mother who was so against gayness and was devastated that she had a gay child. You cannot say, “ah come on…” This is not how it goes. The pain and sincerity of this woman were real and not made up. It was because of her fear; fear for her child in those little communities where everyone knows how hard it is. So you have to hold who they are even if you don’t agree with them, you have to hold them. A love that sees people the way they are and accepts.

The Secret Garden

The 3 acres of gardens that belong to Bleanáskill Lodge were established around 1870. Situated on a peaceful oasis on Achill Island, along the Atlantic Drive, the lodge can be found in a quiet hamlet, two miles from Achill Sound. From here you have a view over to the Curraun Peninsula and the waters of the Sound. Although constantly challenged by fierce winds and salty air, over a century of various owners, has resulted in a mixture of mature trees and colorful borders, art features, and vibrant wildlife. Willem and Doutsje, in residence at the lodge and garden caretakers for over two decades, transformed the gardens into what is known as Achill Secret Garden. The slide show follows Doutsje as she walks around the gardens where we see tree groves, sculptures, ornamental and vegetable gardens, bridges, meditation areas.7

Willem Van Goor: The Artist and the Fringe

I was always interested in nature, mostly in insects and plants. Between the age of 15 and 17, I became kind of annoyed with the way plants were presented in general guide books that illustrated all of the flora of the Low Countries. The illustrations were all done in black and white. So I started to make botanical drawings of plants and I did microscopic work because at the time I wanted to be a biologist, I didn’t think I was going to become a painter. But then I ended up in art school. You are formed in an environment, swimming around in it like a fish. There were abstract pieces, sculpture, wood and metal work, and I did ceramics. I did that work for years and years, after a time recognizable subjects started creeping in, images influenced by nature – grasses, clouds, visual worlds – shimmering through the abstract work. I also did a series of portraits of women. After my last exhibition in the Netherlands we emigrated and soon afterwards I began to reconnect with nature. I started to look at the landscape again and it’s one of the reasons I am here. Driven by an interest in what’s behind the scenery, I started to immerse myself in our surroundings. I did a whole series of houses and of weather systems approaching, not romantic pictures of the rustic village, but rather, the barren shot, the strange colors of Achill and County Mayo, especially in winter, when there are no tourists.

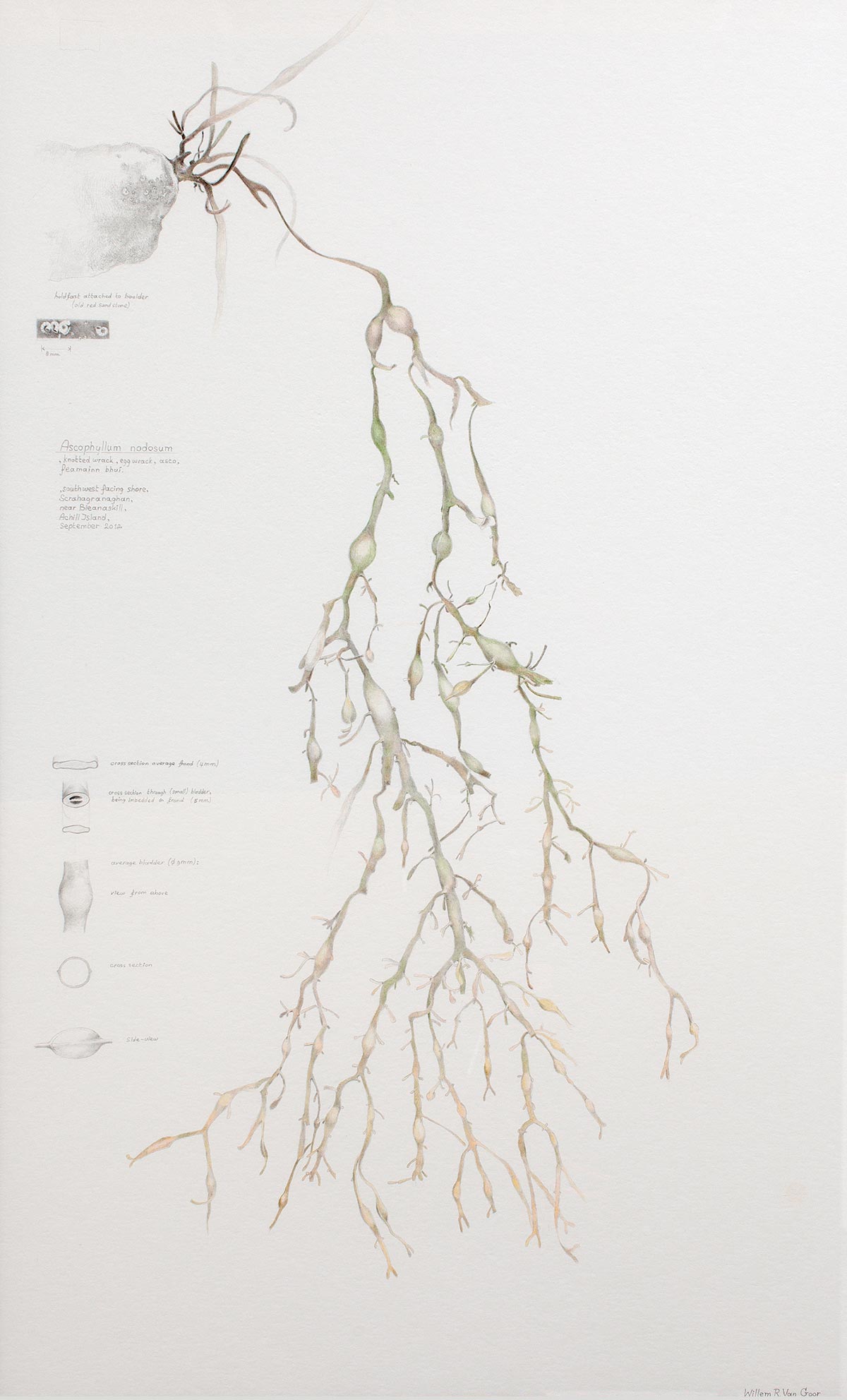

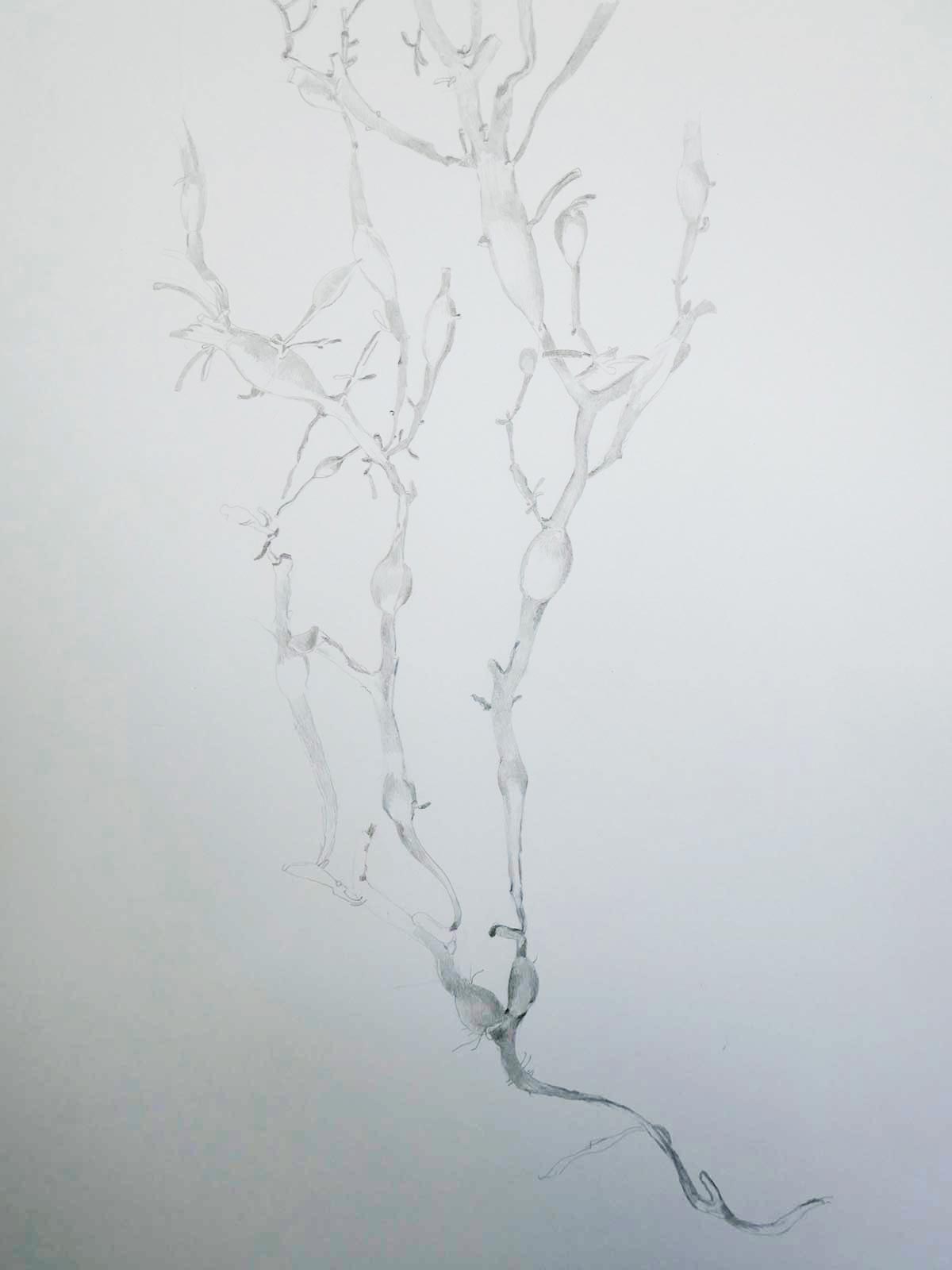

After some time, I noticed my focus was broadening. The surfaces of things and their hidden patterns captured my interest – the soil, seaweed, and the myriad of plants in the garden. These surfaces brought me back to a kind of abstraction. For example, you can redefine grass in an abstract way or see that seaweed has a certain structure that repeats itself in a particular way. This in turn brought me back to the botanical drawings.

Such work often leads to commissions. For example, the great great nephew of Alexander Williams, the artist and writer that once owned Bleanáskill Lodge, who established the Water Lily Society, specializing in water gardens, and is a founding member of the Gardening and Landscape Society of Ireland (GDLA), asked me if I could do a drawing of a particular water lily.

I also did one of seaweed that I sold to a biologist. I do them on order. I love to do these works as they bring back my love for nature.

I am most interested in exploring what the landscape is doing, being on the fringe of the landscape, where the ocean meets the land, where seaweed is washed ashore, and what happens when a river runs havoc in a valley. For example in Morocco where in the winter the current brings plastic and rubbish from the villages and towns and leaves it hanging in the willow trees and when the river dries in summer you get a kind of border of plastic at a certain altitude amidst the flowering and blossoming trees.

People don’t look at seaweed, it’s slippery, you avoid it if you don’t want to eat it, and we don’t want to see the plastic in trees in a river valley in Morocco. For me it is a special thing, human interference. On the fringe of what is nice and not nice has my deepest interest. What’s visible and not visible, how to make it visible and to see the beauty of it, effectively you are back in the structure, back in abstraction, and it can go everywhere.

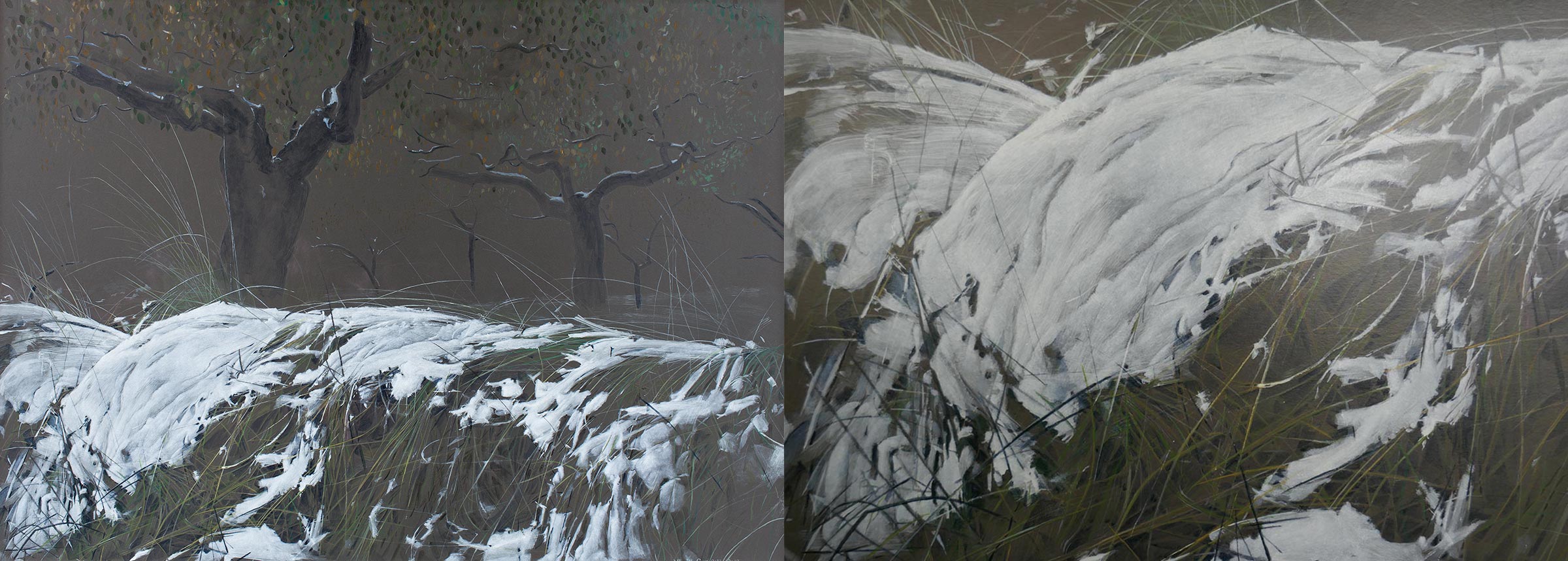

The same goes for snow. I’ve always been mesmerized by snow, to see what it does on grass, on stones, on the beach, on seaweed. It’s a process. I look for a focus point, where it comes to a standstill, where it broadens, both in the same frame of development. They are zones of liminality where abstract and concrete thinking come together. It’s in music, rhythms, maths….

When you look at grass what you see is a bunch of green blades, a mostly upright and short species, but on a closer examination you can see an abundance of forms. When you do that you have to find the commonality, the pattern, maybe it’s the wind that is creating that pattern. There are thousands of species of grass. They each have forms – attached to the blade in a certain way – each species is different. They have strong genetic patterns. When you have 20 of them together you can see there is an architectural and mathematical structure, that is abstract and you can bring it into relation with music.

I have a strong interest in these mathematical orders, in rhythm and rhyme, and commonalities. Often what’s in common is not what people expect. Being in a certain place, stirs my curiosity. I always try to find out about underlying structures, yes again, the rhythm, deep, be they stones, plants or human beings, the layers of biology, geology and history. However, there’s always one big fat but: if you go too deep, you can get lost and end up with empty hands…Whether an artist or businessman, you need focus, to know the ins and outs, the bolts of things. I want to know about the bolts, where they are, and what people do with them.

I can dive into the world of blades of grass for weeks on end and I’ve done that my whole life. I don’t depict people. I talk, invite, and can be with people from early morning to late at night but I don’t paint them.

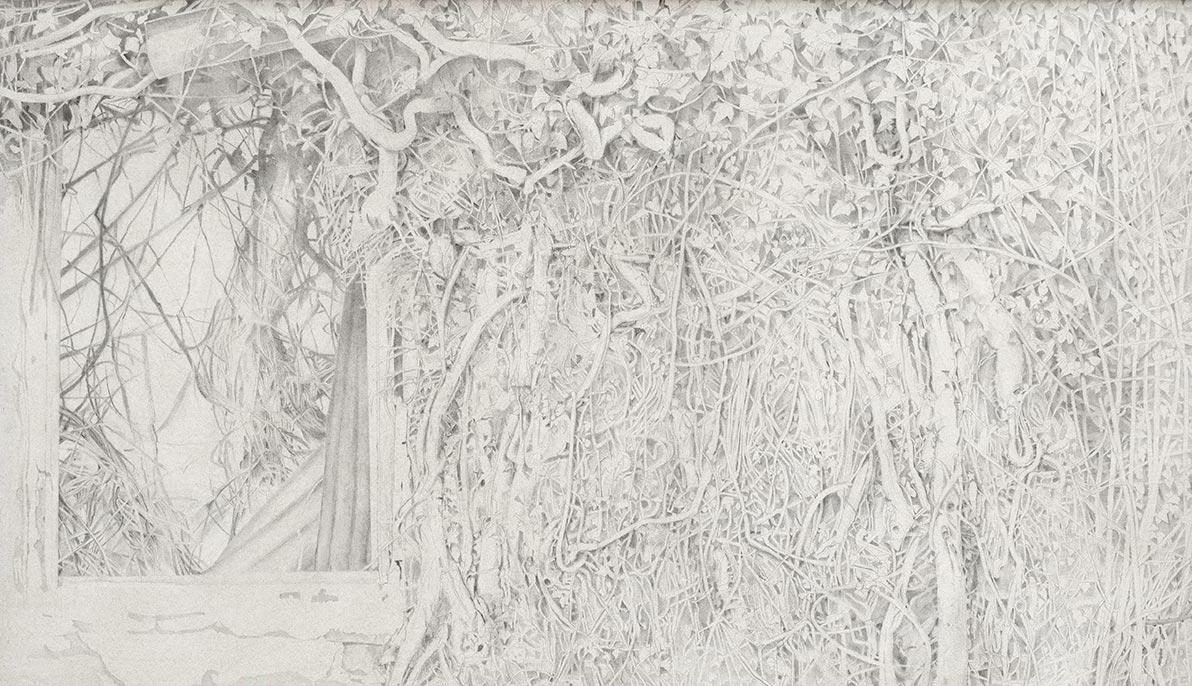

Jessica – When I look at your landscapes they feel “peopled” to me.

Willem – I don’t know. I know they have their own characteristics and I love them. For example, the kingdom of the wren, the little brown very Irish bird that lives in shrubbery or a cottage overgrown with ivy, a creeper with glossy green leaves that covers, climbs everywhere, the stems can crush stones, like the world of the wren. In depicting that particular world, I look at how the ivy attaches itself; this mass of structure – ivy structure – only ivy can do that. Drawing, painting, this process is like a jigsaw puzzle, a kind of relaxation, or musical rhythm, and an abstract repetition of forms. This is what I am drawn to, the structure of ivy, the formal patterns of ice and snow, grass or seaweed, there’s always something happening…

Jessica – An encounter.

Guilherme – The rhizomatic spreads. It’s horizontal. It doesn’t create deepness, rather its structure embraces constantly moving, shifting, and multiplying surfaces. Like fractals. It is both a mathematical process and entirely random.

Willem – Look at this example of seaweed. I also collect seaweed. Here’s another one. See the structure and the randomness together…

Jessica – Oh that’s so beautiful!

Willem – Yes, very beautiful. I have many more studies. You need all these studies to do a piece on a real scale. Another example, here is a willow, you can see the willow structure, it has a certain language. I make a choice to work in greens and olives, with sparkling blue and white. I draw while studying and sorting out forms, working in different directions and colors. The tulips are so white and shiny, I leave them untouched, to make a point. These things are not photographs. How to draw or paint snow? Snow is white, so keep it simple, you leave the snow white and you do the rest. It’s a choice you make, you build the clarity of the picture in a graphic way, playing with the snow and the shadows, than with paint, and you discover ways to depict snow on grass, with different emphases.

Guilherme – Understanding of structure is key.

Willem – Yes, but you only find it by doing it. Forms, colors, studies…

Guilherme – A universe of difference and structure.

Willem – You have to focus on one thing at a time, then on another thing. When I was young I studied the piano and organ about 2 hours a day. After that I did my homework. Then I was drawing plants. Then feeding my seawater aquarium.

Jessica – Music seems to inform everything for you, a generative force.

Willem – Music was first, I was even playing rubbish on the organ when I was about 3 and managed to start making tunes when I was about 4. Music came first, then insects, then painting and drawing.

Guilherme – Musical structure and abstract thinking come together. Perhaps this is fringe thinking. The complexity of different species living together, in your paintings you can grasp that encounter, that we are part of the grass.

Yes, we are made of the same “stardust.” I want to focus on things that people never look at tWillemhat they should look at.

Jessica – The fringe maybe is holding that consciousness, seeing something normally not seen, of holding that awareness.

Willem – Maybe it is a feeling for the fringe…Mud, stand, and stones are not very fashionable, but you have to paint it before people recognize that there’s beauty in it. I’m not a preacher man. I’m just doing it because I love it myself. I’m interested and connected to it, that’s the reason I paint it.

Guilherme – Art offers new approaches to everyday life.

Willem – Fringes with an “s”.

***

Doutsje Nauta

Was born on a stormy night on January 31st 1953 in IJsbrechtum, The Netherlands as the second child and first daughter. Reviewing her working life, she has spent most of the time organizing and writing in (semi-) governmental institutes. Innovation has been the common thread in her work. She has been living on Achill Island since 1997, a place that while isolated from major world events is nevertheless an integral part of them. This positioning feels characteristic for how she sees herself in society. She is a long-time member of the Achill Writers’ Group and has been studying to play the cello since autumn 2017.

Willem van Goor

Was born the 4th of November 1948 in Zwolle, The Netherlands. After secondary school he studied for five years at the Art Academy in Groningen and specialized thereafter in lyric abstract painting. His work has developed since and become more diverse, comprising botanical art as well as landscape painting. His botanical work is grounded in a lifelong love for nature. The landscape work, with its focus on hidden structures, parallels the rhythm and chords found in music, another lifelong passion, improvising and playing both piano and organ.

Revd Val Rogers

Is from Sligo in the West of Ireland and became a Roman Catholic priest in 1972, serving in Fiji and Sydney until 1984. He married Josie in 1985 and resumed his calling as priest with the Anglican community in Melbourne until returning to Ireland in 2009 as Rector of four Church of Ireland [ie Anglican] parishes in West Mayo, including St Thomas’s Dugort on Achill Island. He and Josie retired locally in 2019.

1 Paul Durcan, “The Far Side of the Island,” The Art of Life, (London: Harvill Secker, 2012 (First published 2004) p. 11.

2 Conversations with Willem and Doutjse and also noted in Patrick Comerford, “Under Blue Skies Achill is Like an Aegean Island in the Sun,” St. Thomas’ Church: Dugort, Achill Island, Co. Mayo, Ireland (Dublin: Society for Irish Church Missions c.2012) pp13-16, p.15-16.

3 Tom Gillespie, “Starving Achill Families renounced the Catholic faith for food handouts” Connaught Telegraph, January 9th 2021, available online: https://www.con-telegraph.ie/2021/01/09/starving-achill-families-renounced-the-catholic-faith-for-food-handouts/

4 Ibid.

5 For more information see: https://wwoof.net/about-2/

6 Henry David Thoreau, Walden; or Life in the Woods (First published 1854) (New York: Dover Publications, 1995) p.11

7 For more information on the Garden and a selection of photos and videos see: http://www.achillsecretgarden.com/