Identity Essay 2005-2020: Mayra Martell

To miss: To be away from who inhabits you.

Text: Joana Mazza

The intimate life captured by Mexican photographer Mayra Martell in Identity Essay (Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. 2005-2020) presents preserved vestiges of the existence of missing girls and young women from the notorious city of Juárez in Mexico. This city bordering El Paso, Texas, USA, is known for major international makeup factories and gender-based violence. Despite the lack of reliable sources on the number of victims, according to data from the integrated women’s network Mesa de Mujeres de Ciudade Juarez, between 1993 and 2015, a total of 1,459 cases were documented. Of these, the largest concentration occurred between 2007 and 2013, totaling 70% of those missing. Among the cases that Martell has keep track of, only 30 bodies have been found and less than 10% have had the culprits identified. According to the Argentine anthropologist and activist Rita Laura Segato:

The city of Juárez, in the state of Chihuahua, on the northern border of Mexico, is an emblematic place of women’s suffering. There, more than anywhere else, the saying “cuerpo de mujer: peligro de muerte” (woman’s body: danger of death) becomes real. Juárez is also, significantly, an emblematic place of economic globalization and neoliberalism, with its insatiable hunger for profit.1

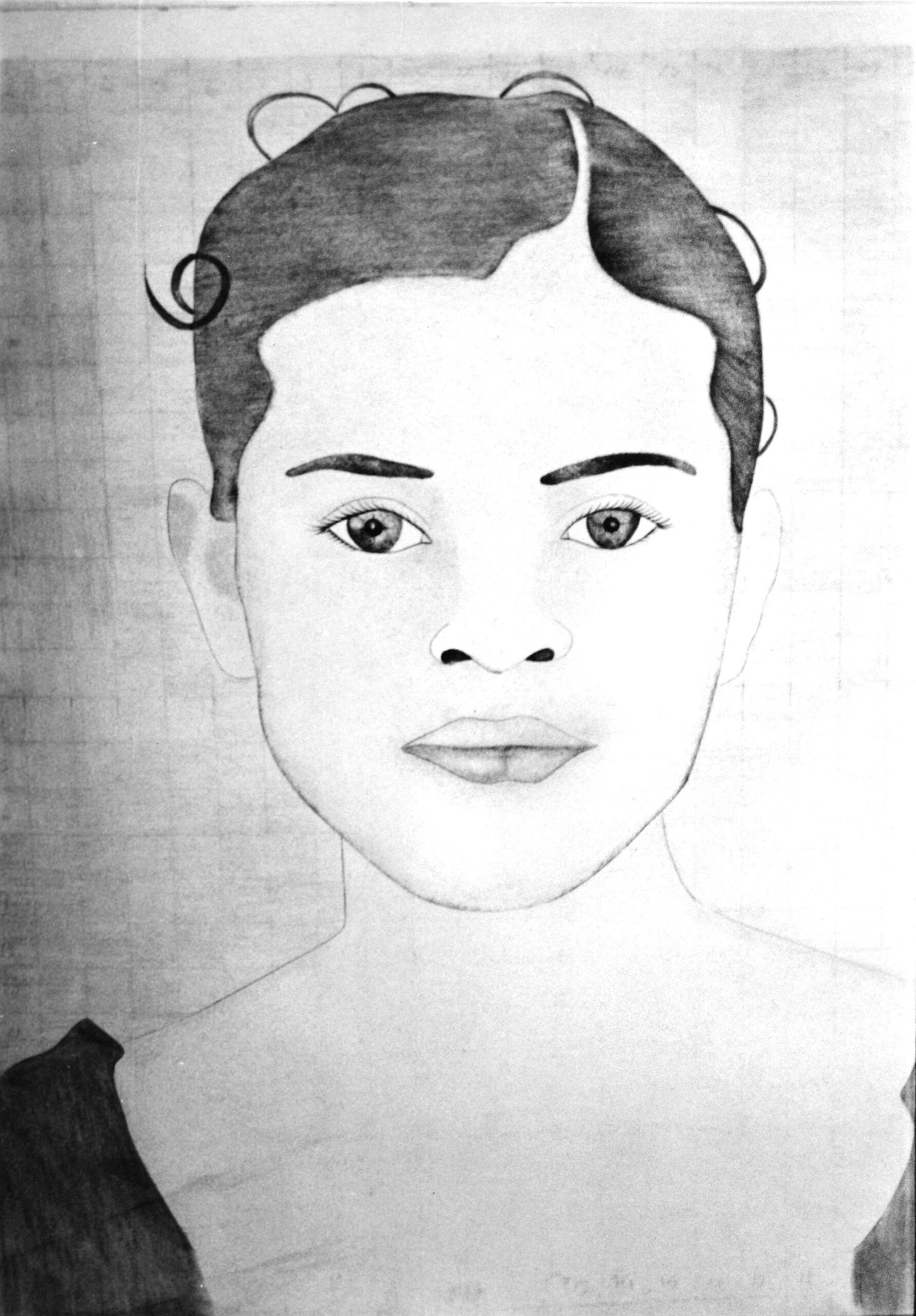

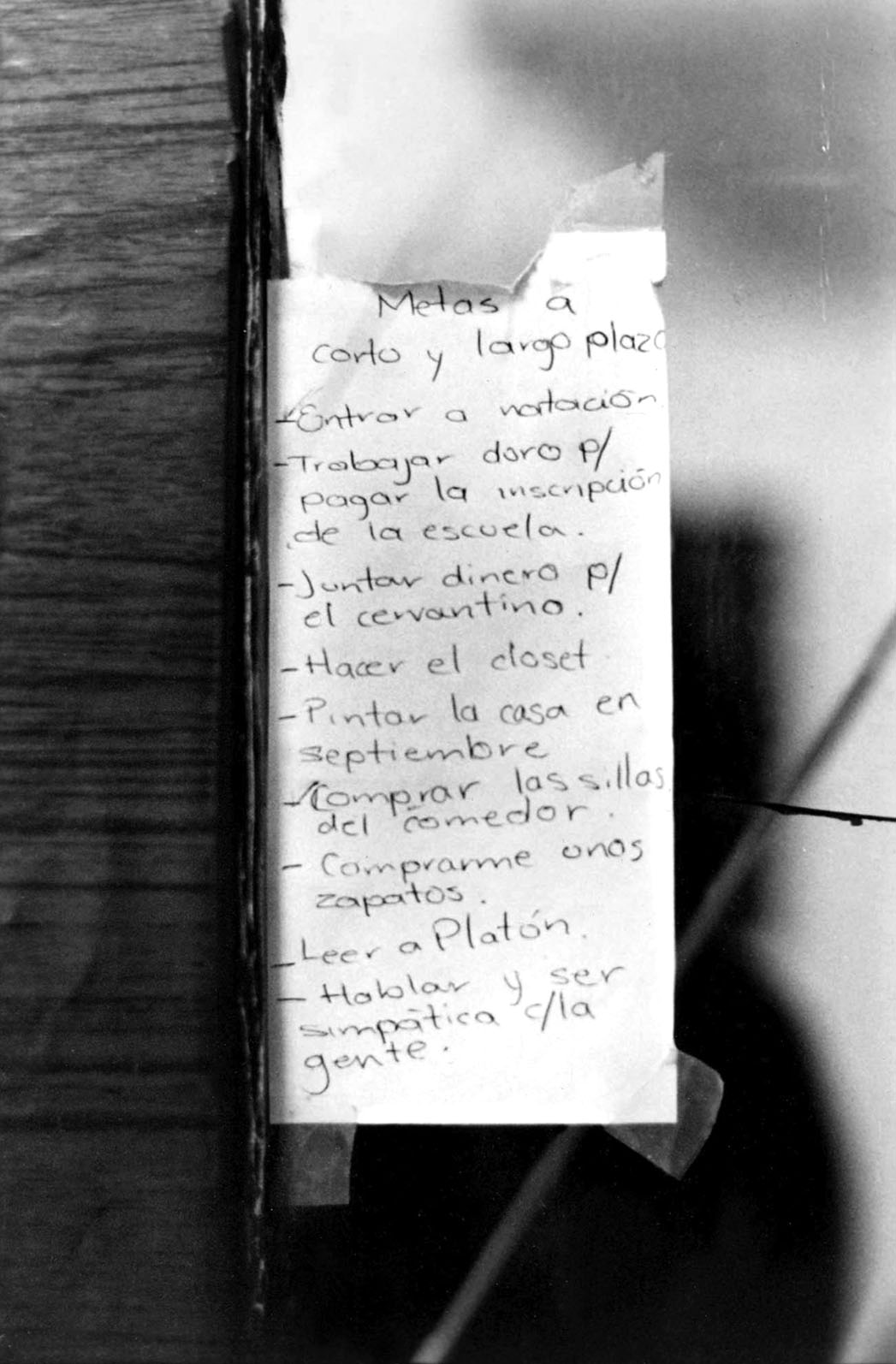

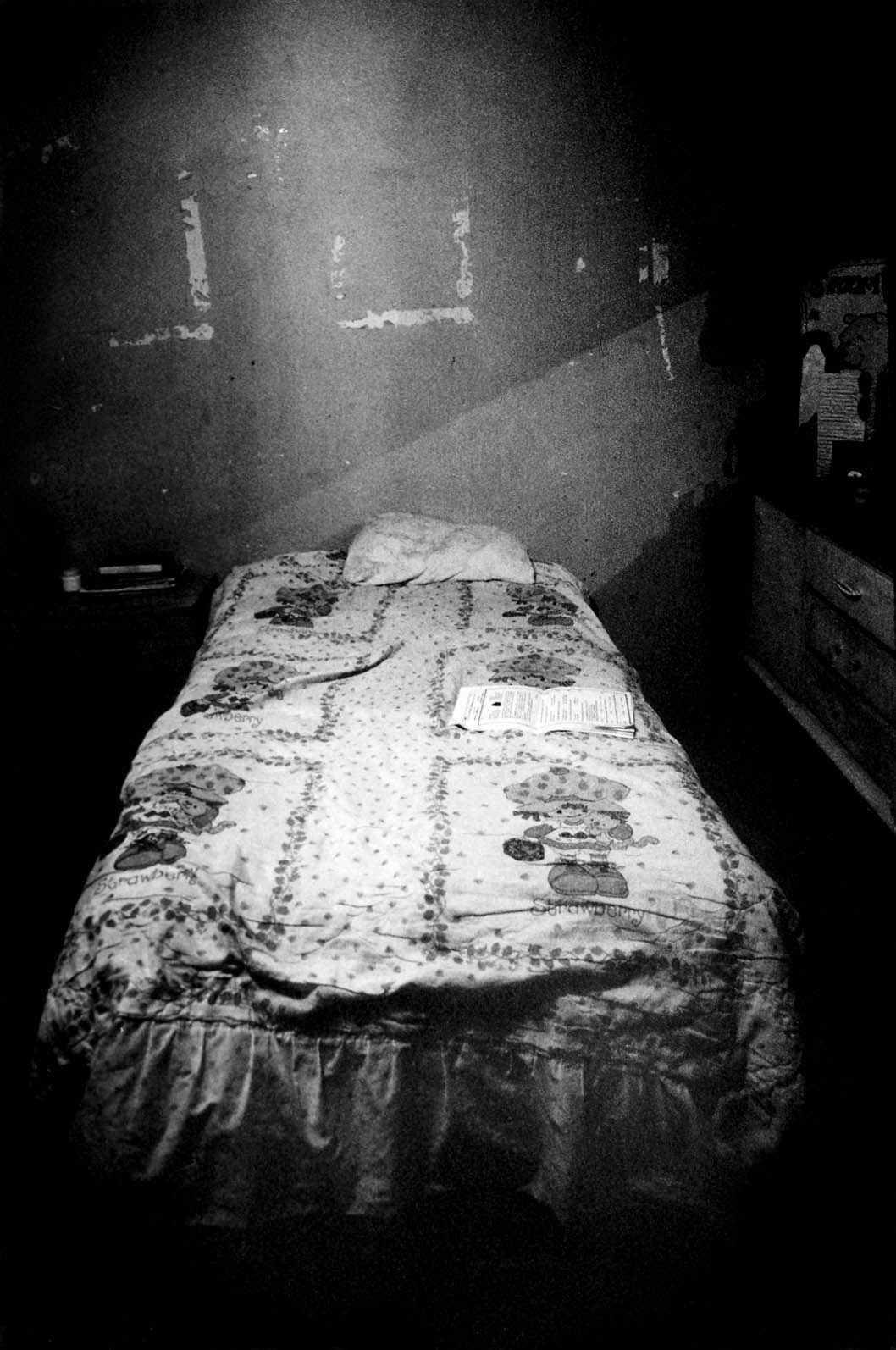

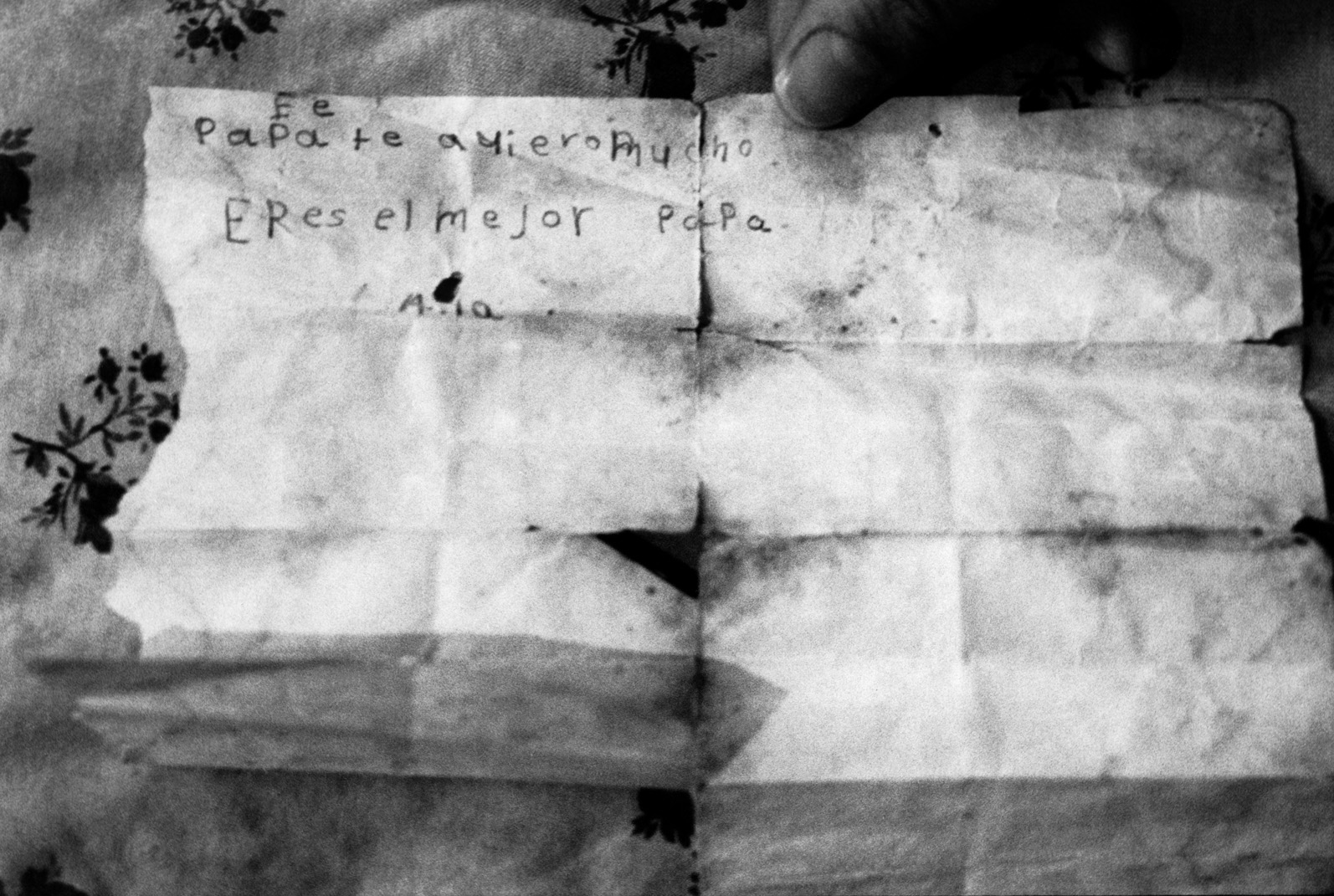

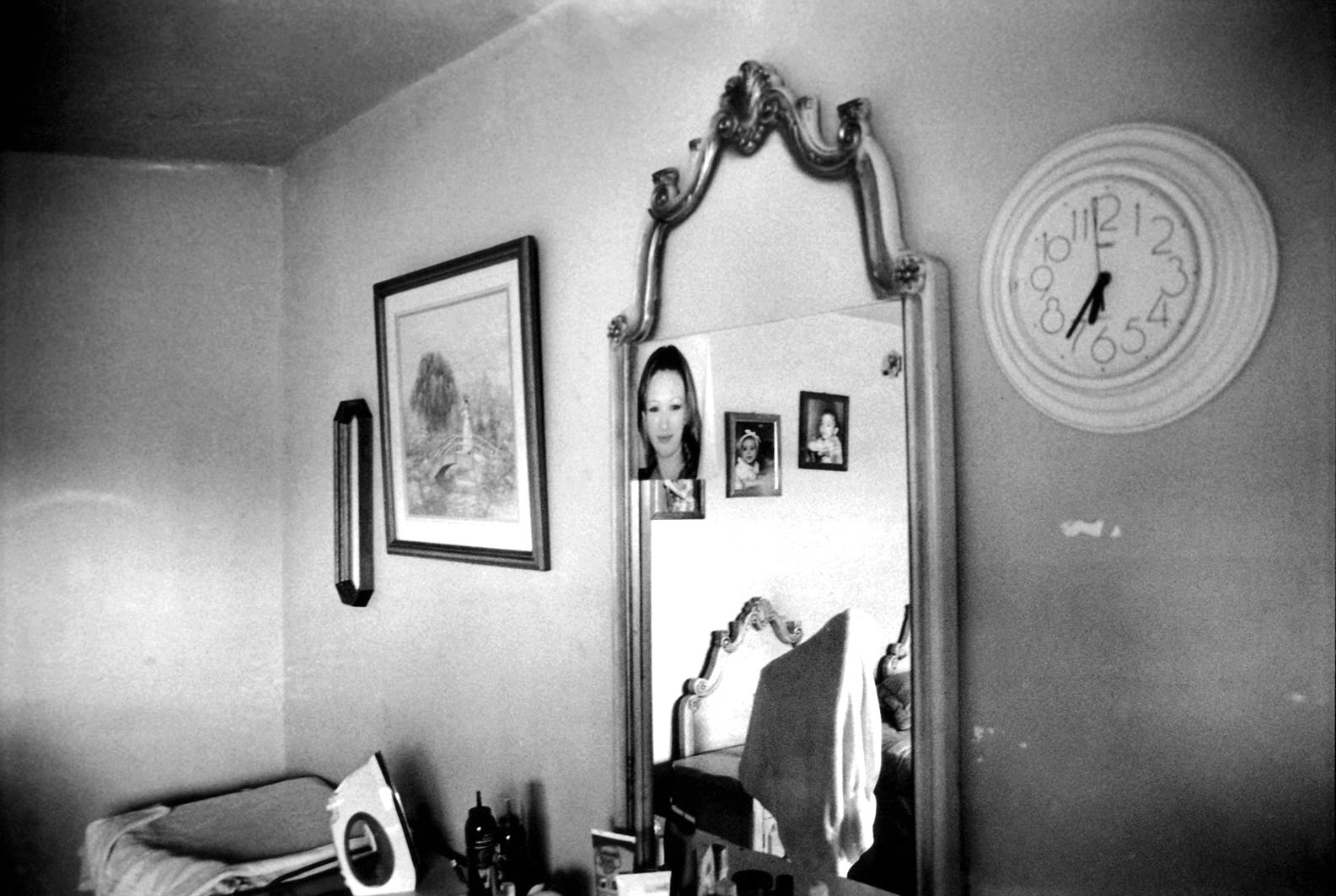

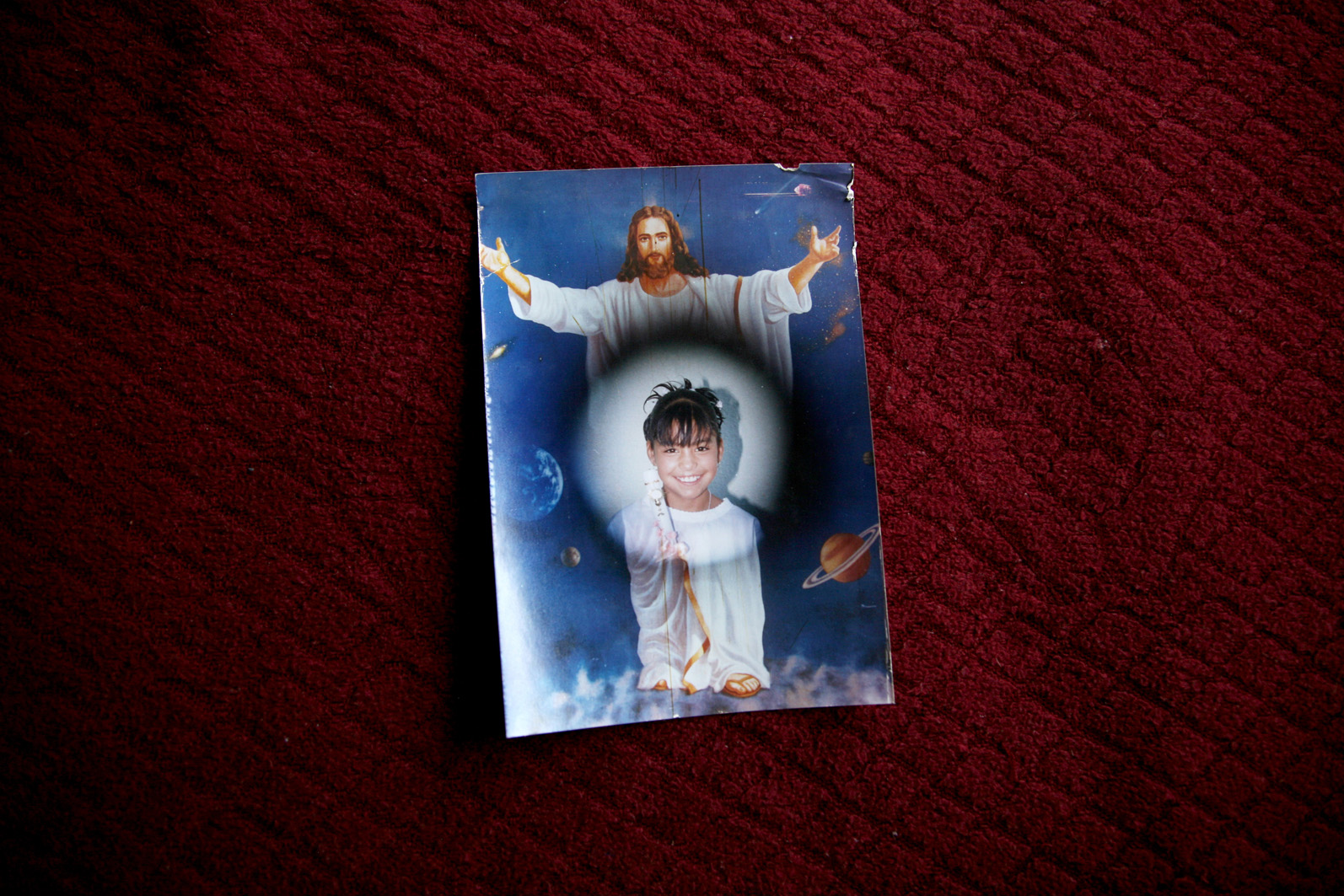

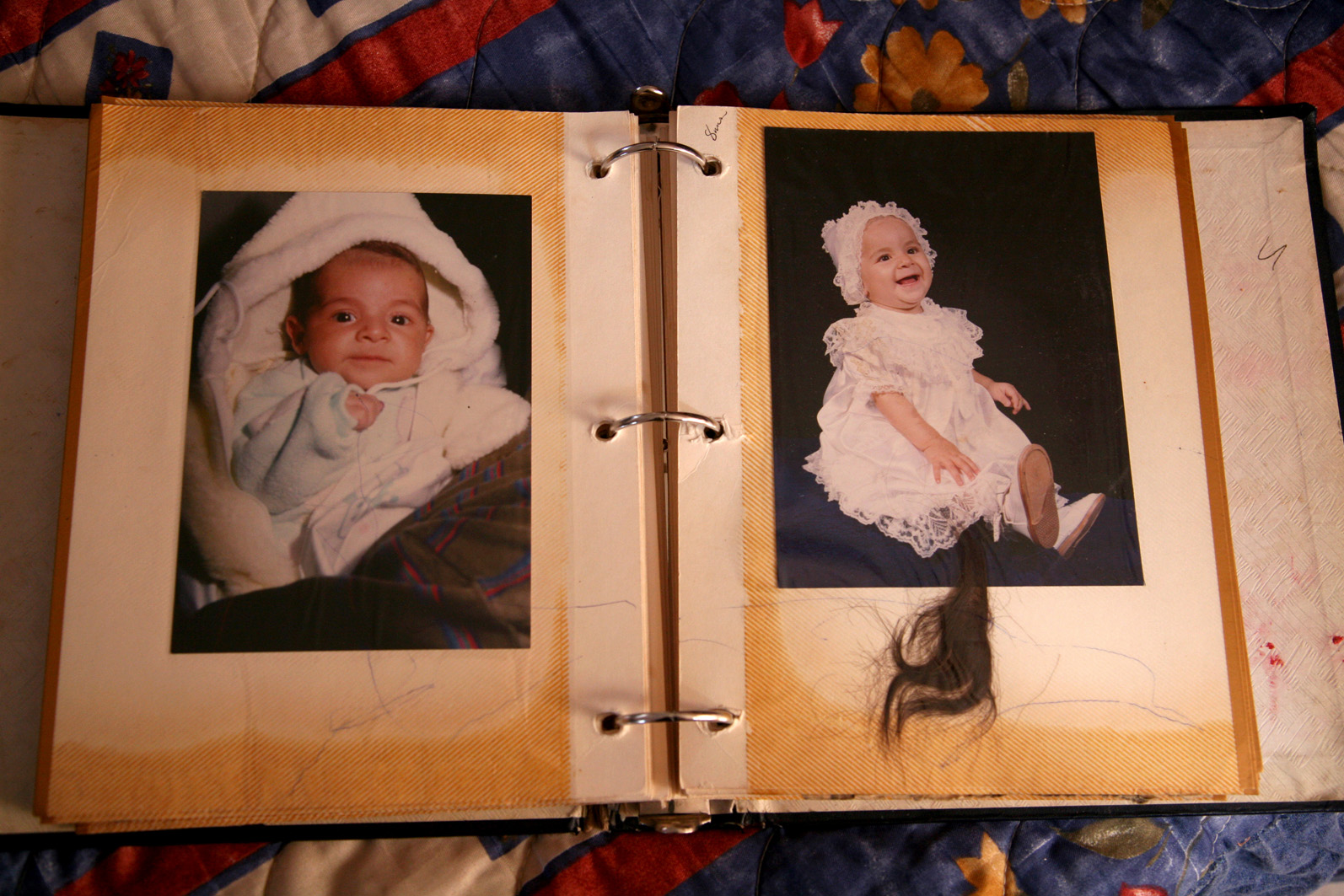

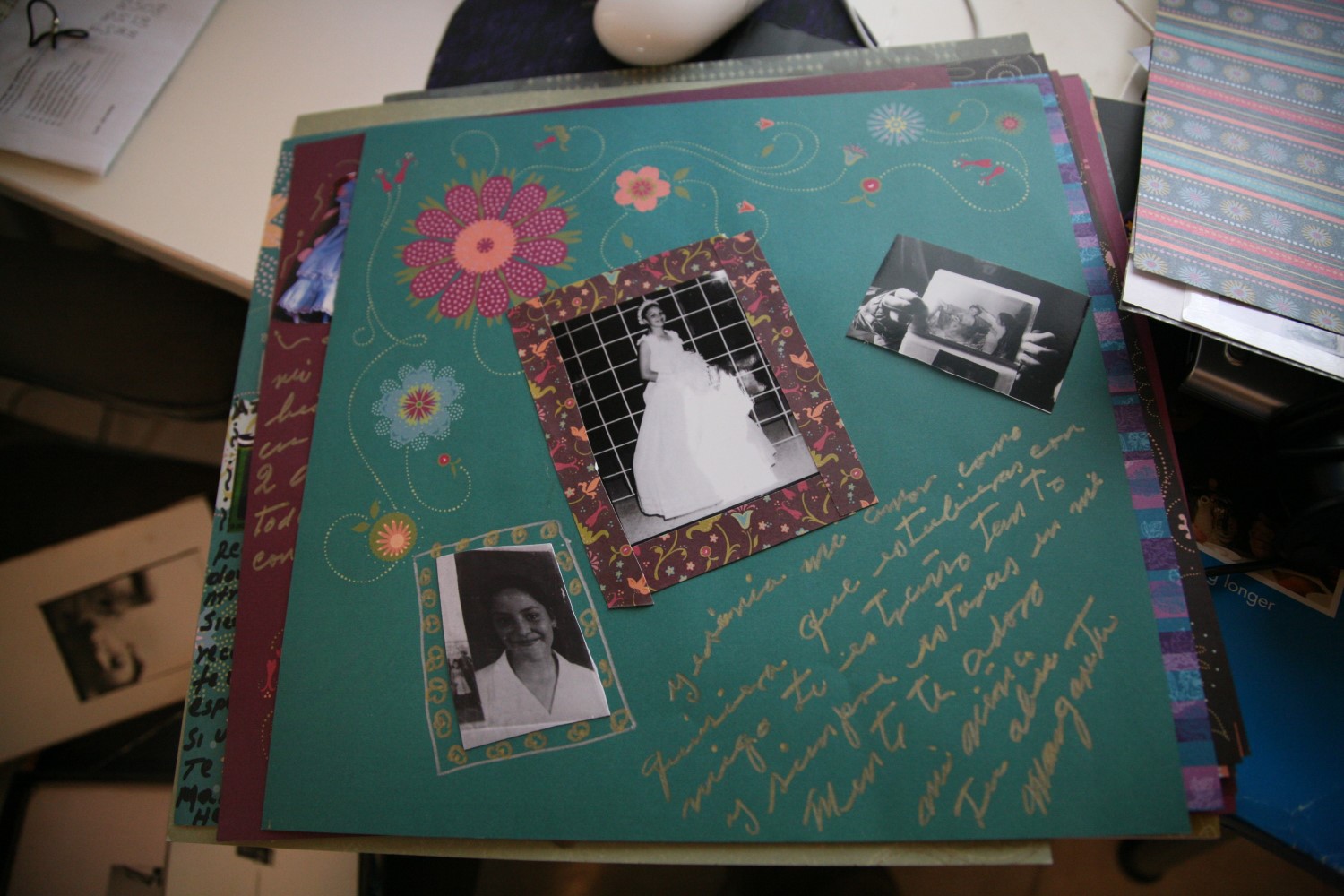

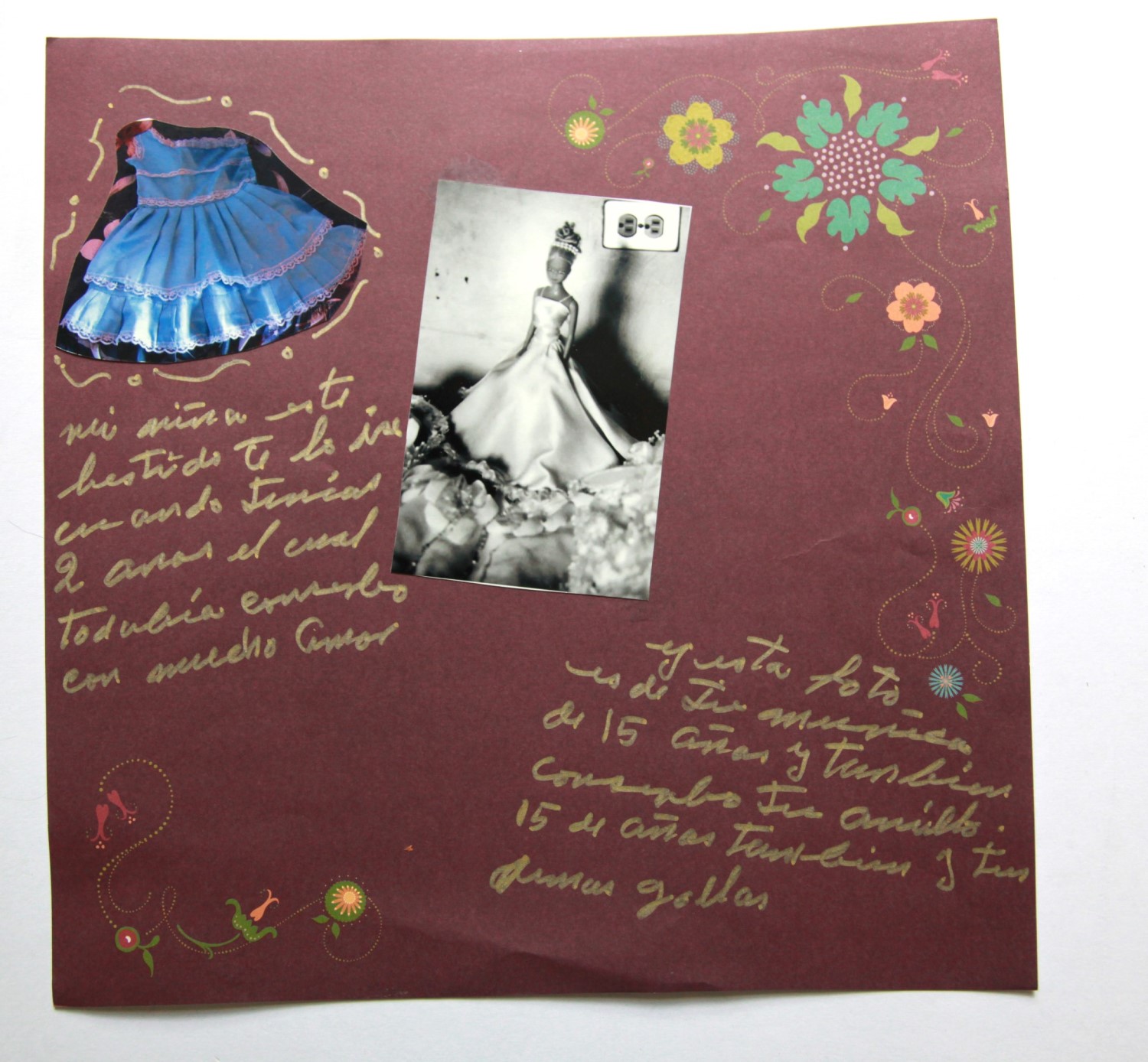

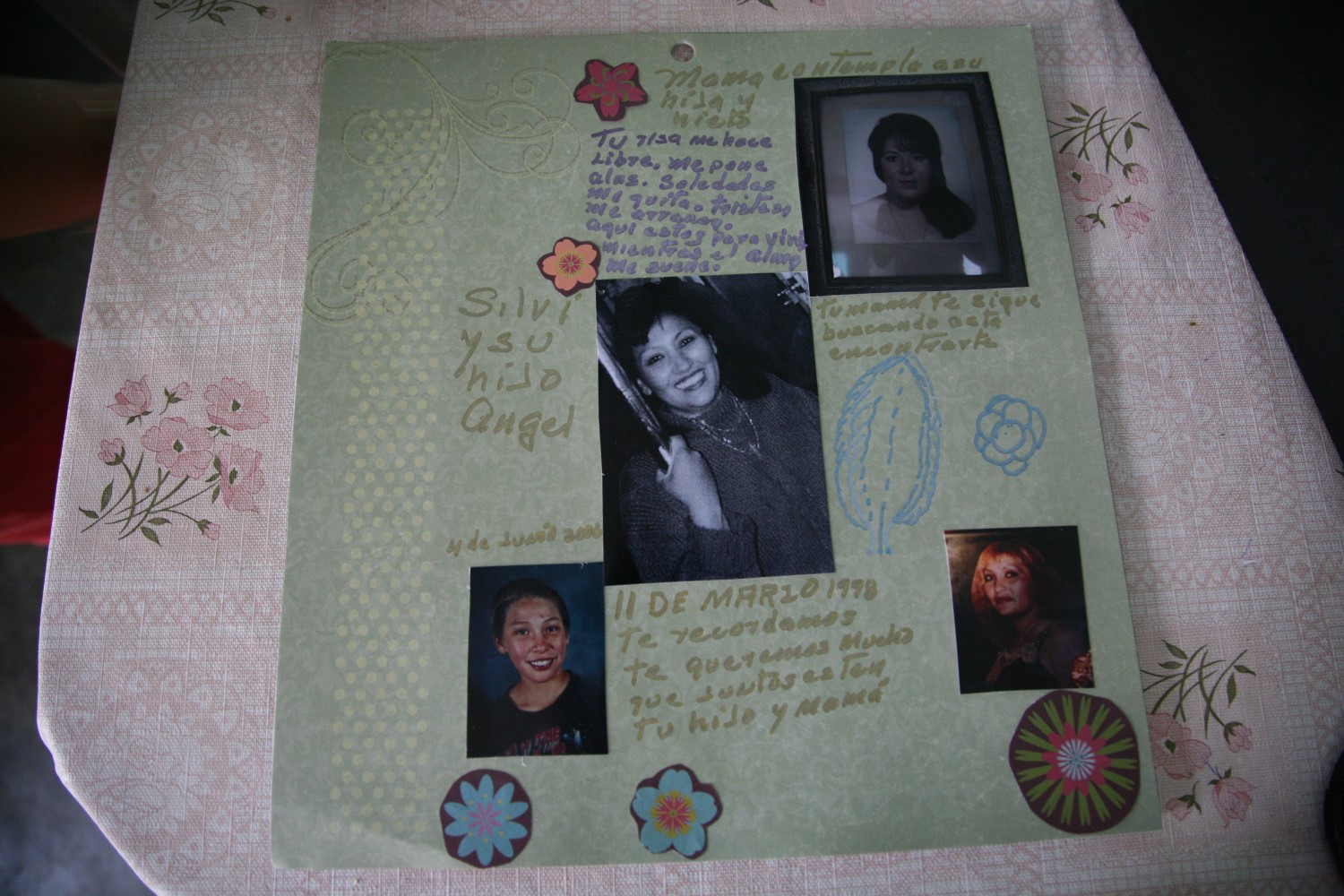

Countless families are not only plunged into heartbreak, dealing with the pain of missing their loved ones, but also the knowledge of the assured violence of their loved ones fate, not knowing if they are alive and suffering terrible trauma, or dead. Making matters worse, they are further impacted by the continued cruelty of the authorities’ inadequate response. Unequal extremes: On the one hand are these families, hidden in the vulnerable areas of the neighborhoods far from the center of Juárez, on the other society’s complicity in these tragic destinies. Martell’s intimate portrayal of absence both exposes this violence and also the resistance against it. These rooms are not empty. They are full of memories, traces of personalities, and the last vestiges of each victim’s existence. The careful safeguarding of these spaces is [the only] means of perseverance against the destruction of these lives.

Mayra Martell is from Juárez. Returning to visit in 2005, walking in the city center, she notice the walls covered with missing person posters, portraits and messages from relatives desperate to find their missing daughters, sisters, and granddaughters.

The first women whose cases I documented were curiously my own age. Visiting their rooms reminded me of myself a few years ago. Their mothers looked at me for a long time and spoke of their daughters as if I were an old friend. I was attempting to create an image, to reincorporate memories of them so I could know them.2

In her photo essay, Martell sought to recover the few existing vestiges of these victims from the most vulnerable strata of Mexican society. Despite the passing of time following the victims’ disappearance, the preserved environments not only present the portrait and history of its residents, but also the result of a violent and corrupt society.

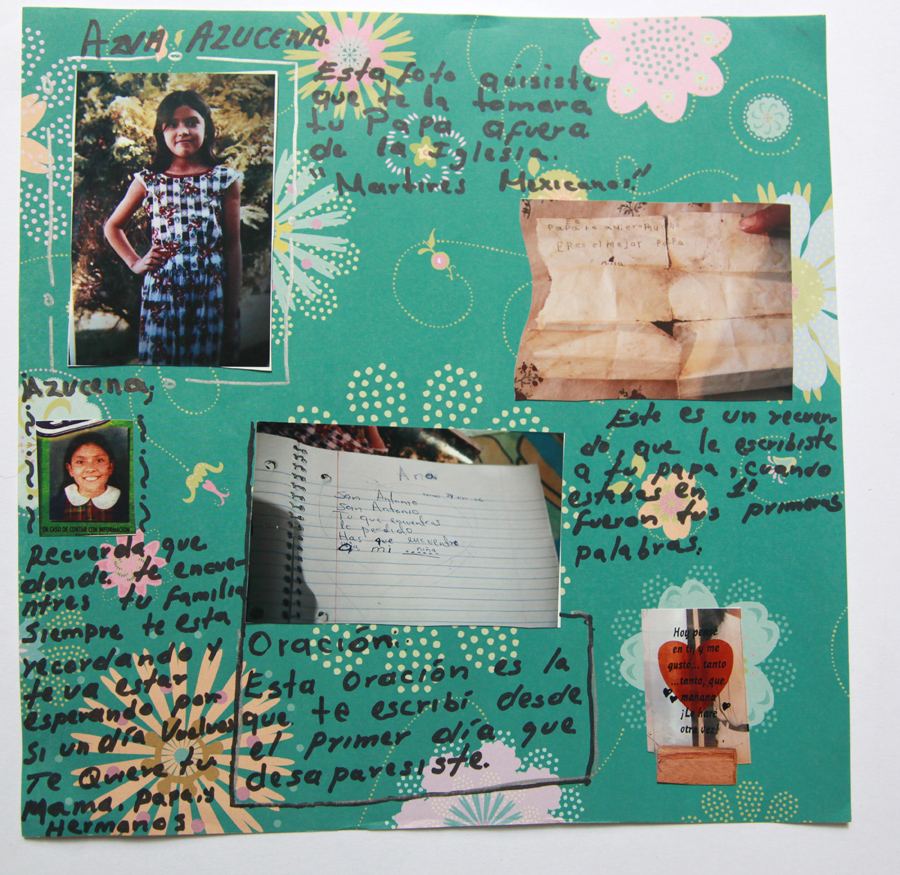

“At what point will these women become fictional?”3 Martell here questions the tragic invisibility of these disappearances. The missing posters wheat-pasted on the walls throughout the city center do not seem to have had any impact on raising awareness or drawing attention to these disappearances that continue to increase each year. In response, combining her photography with activism, in 2012 Martell founded Diário Latinoamericano [Latin American Diary] an initiative that draws on the resources of art and culture to transform the experience of pain, reconstructing life stories both as narratives told by those affected and as instruments of denunciation.4 Among the actions Martell carried out is the artistic workshop with the mothers of the disappeared in Juárez, where they worked on their memories through photographs and texts.

The case of Juárez has been researched and questioned by authors such as Rita Laura Segato. In her book La guierra contra las mujeres [The War Against Women] Segato analyzes these disappearances, particularly addressing why their continued re-occurrence seems to have little impact on social mobilization.5 Segato outlines a complex game, where the women’s bodies are used as a space of social and political dispute. Not only victims of kidnapping, rape, torture, or trafficking in persons or organs, these young girls and women are made to bear the extremes of a society that uses the female body as a territory of power. Alive or dead, these bodies are instruments used in a nefarious escalation of power that annihilates their will, uses and discards their flesh as an object, carried out by executioners beholden to the actions of a sovereign power. This wanton disregard for human life has been widely characterized as femigenocide, a charge applied to this city since the 1990s, in which controversial police investigations have so far failed to uncover the causes and the true culprits of these crimes, even though they have numerous elements in common. Part of the radical extremism of a para-state male fraternity, the weak, raped, and tortured are ploys in their power games.

In 2009 Martell was forced to leave the city and move to México City. To this day, her return to Juárez is complex and requires much caution. Despite this, she continues to accompany the families, assist in investigations, and register new cases.

Martell’s committed practice combining photography and activism is not an isolated one. Latin American artists and photographers are increasingly working in a transdisciplinary way, mixing politics, activism, poetics, and history in their work among other possible approaches in their striving to reformulate the social and cultural structures that oppress existence, resistance, and diversity particularly as experience by women. These artists see their work as necessarily activist and as a response to the urgent need for paradigm transformation. Because hope is not enough, we have to do something to change what we want to change.

***

Mayra Martell (b. 1979) is a documentary photographer from Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. She works primarily in Latin America and Africa in territories subjected to political, social, and economical turmoil. In 2019 she was nominated for the Joop Swart Master Class contest. In 2016, she received a grant from the National System of Creators of the National Culture Fund of Mexico, for a project focusing on the daily life of violence and drug-culture in the north of the country. Martell has received many distinctions and awards and published several books. On 2012, she founded the Non governmental Organization, Diario Latinoamericano.

Joana Mazza (b. 1975) is a researcher, curator, cultural producer, and photographer. She is a doctoral candidate in the Postgraduate Program of Contemporary Studies of the Arts (UFF-Brazil) and is part of the Posthuman Latin-American Network. Mazza has a master’s degree in Art, Thought, and Latin American Culture from the Instituto de Estudios Avanzados (Universidad de Santiago de Chile). Project highlights include: the coordination of FotoRio exhibitions (2003 to 2009), the coordination of the program Imagens do Povo (2010 to 2103) at Observatório de Favelas, assistant curator at MAC de Niterói (2013 to 2015), and curator of the Festival de Fotógrafas Latinoamericanas (2021).

1 Segato, Rita Laura. La Guerra Contra las Mujeres. Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños, 2016, p..33.

2 Martell, Mayra. “Ensayo de la Identidad, ciudad Juárez 2005-2020”.

http://mayramartell.com/en/portfolio/ensayo-de-la-identidad-ciudad-juarez-2018-2005/ [Accessed April 30th, 2021]

3 Martell, Mayra. “Quiénes Somos”. Web. 30 2021.

http://diariolatinoamericano.org/english2 [Accessed April 30th, 2021]

4 Ibid.

5 Segato, Rita Laura. La Guerra Contra las Mujeres, op.cit.