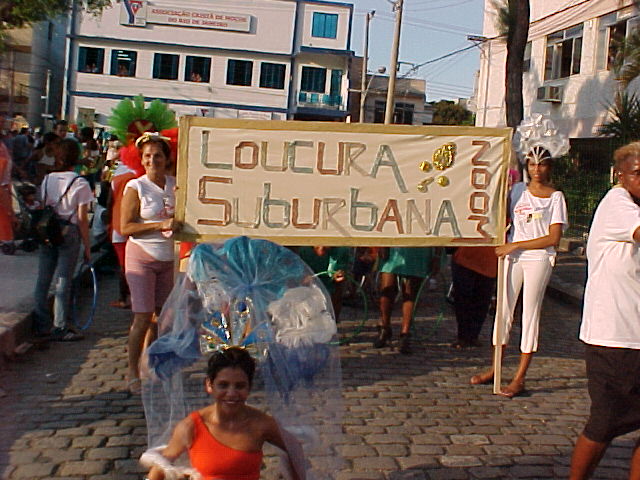

Bloco Carnavalesco Loucura Suburbana [Carnival Block Suburban Madness], Parade, 2015. Photo: Fernando Maia

Loucura Suburbana [Suburban Madness]: “Let’s get going!”1

Ariadne de Moura Mendes

When I was 16 I visited one of Brazil’s largest asylums, a huge deposit of people, whose smell, misery and abandonment left a lasting impression on me – from this moment on the idea of being a psychologist was sparked, I wanted to fight for this population.2 Shortly before graduating in psychology I read in the newspapers about a protest movement that was occurring a well-known asylum in Rio that had been started by a young doctor who was denouncing maltreatment and terrible working conditions. I was really curious to get to know this hospital. I had heard that they were also developing a therapeutic community experience and a democratic management of the operation of a psychiatric ward. So I went to visit. On leaving that place, I felt I wanted to work there one day. It was the 1970s and the hospital was the Pedro II Psychiatric Center (CPPII), in Engenho do Dentro suburb of Rio de Janeiro, what is now the Nise da Silveira Municipal Institute of mental health.

Decades later, in the early 2000s, after working on the institution’s reconstruction process that had begun in the 1980s, I took over the directorship of the Ambulatório Central [Central Outpatient Clinic] where the Art Workshop was created.3 And it was there, in a reversal of the proposal to hold a carnival party for the patients inside the institution, that the idea arose of “breaking” the walls and of creating a carnival bloco that took to the streets, as an important initiative in the promotion of social integration and the struggle against the stigma of madness [T.N. Blocos are neighborhood carnival celebrations combining music, street parades and festivities]. Thus was born the artistic and cultural work of the Bloco Carnavalesco Loucura Suburbana [Carnival Suburban Madness Bloco] and, later, the Ponto de Cultura Loucura Suburbana: Engenho, Arte e Folia. [Culture Point: Suburban Madness: Mill, Art, and Folie. T.N. Pontos de Cultura are community cultural centers throughout Brazil supported by government funds inaugurated by former Cultural Minister Gilberto Gil (2002 – 2006) with the goal of fostering local “points” of culture. The idea was to work against centralizing and traditional practices of “bringing culture to the peripheries,” and to operate more like acupressure points, that is to invest in the cultural energies already present in the locale and build a network of support that would further enrich/work on what was already in place locally].

Loucura Suburbana is part of the political and historical context of Brazilian Psychiatric Reform in two significant ways. As an organization operating within the Instituto Municipal Nise da Silvera, the first of these is as successors to the legacy of the pioneering work of the psychiatrist Dr. Nise da Silveira in the intersection of art, culture and mental health. A true landmark in psychiatric reform, Nise radicalized treatment with art therapy workshops in the late 1940s, creating the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente [Museum of Images of the Unconscious] in 1952 in the actual asylum itself, both to house and study the body of work developed in these workshops. Her work demonstrated to society the possibilities of an artistic approach as being extremely beneficial to patients’ mental state. However, existing as a space of freedom and promoting a new understanding and approach to the question of madness, the museum was nevertheless like an oasis in the desert. The hospital structure up until the 1980s was still a totalizing institution, in which hospitalization was the method of treatment par excellence. Patients attending the museum’s therapy workshops continued to be hospitalized, returning to their “prison” hospital pavilions after their sessions in that vanguard sector of the then Pedro II Psychiatric Center (CPPII).

The second significant aspect influencing the work of Loucura Suburana and facilitating our leap into the world of art and culture was the movement of the mental health workers at the Instituto Muncipal Nise da Silveira, at the time still CPPII, which began in the 1980s, continuing through the 90s, in which I include myself. This movement enabled a whole restructuring, a true revolution, so that the institution would lose its contours of imprisonment and move towards an opening up to the outside that would in fact be the end of the asylum itself.

Another Form of Care: Institutional Care

Fig 1. Bloco Carnavalesco Loucura Suburbana, Parade 2018. Photo: Marcelo Valle

If today art and cultural initiatives in mental health have independent spaces or operate within social assistance services themselves, it was because there was a care of the institution. Mental health workers did not make art, but they took care of the institution – another kind of care, in which great transformations in social assistance were promoted so that, a few decades later, art could expand, so that there would be more and more spaces in which culture and art in mental health could thrive.

The work of restructuring social services and the changing of the logic of the asylum happened slowly, bringing about a new order in the conquest of freedom that sought out new spaces of work and new institutional practices. One of the fundamental aspects of these changes was the creation of multidisciplinary teams, where professional roles, previously subaltern and secondary, now became protagonists, constituting a collective knowledge in the place of the ever hegemonic, medical discourse of centuries past. Thus, psychologists, nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, and other roles gained equality in teams that also included doctors and as such were able to promote the restructuring of services with in a more humane manner, working amidst the daily struggle against violence and disrespect that is a characteristic of asylum life.

Taking shape over the course of a decade, this movement, made possible due to the forming of multidisciplinary teams, was able to break the dominant cycle – hospitalization / readmission / chronic illness – with the gradual and collective construction of a work practice that simultaneously embraces and takes a calculated risk with the anti-hospital model. This featured the creation of the Central Outpatient Clinic and the concomitant gradual reduction of beds, the creation of the internal living situations, and a network of distributed Psychosocial Care Centers (CAPS), etc. Within these contexts creative workshops began to be offered along with services were introducing art and culture.

Our History: The Bloco and its Historical Importance

Fig 2. Bloco Carnavalesco Loucura Suburbana, Parade 2018. Photo: Archive Suburban Madness

It was exactly in this context, in the early 2000s, through a process of institutional transformation that had already been underway for some time, that it was possible to embrace the idea of a carnival bloco that, instead of reproducing intramural asylum parties, as had been practiced for decades, would take to the streets. Here, “the bloco” would be part of Carnival, Brazil’s biggest popular festival, involving music, dance, costumes, and creativity, indelibly linked to Brazilian roots and as such, deeply connected with people’s identity.

Created in 2001, and it is worth emphasizing again – as part of the process of deconstruction of the asylum model of the Nise da Silveira Municipal Institute – the Bloco Carnavalesco Loucura Suburbana broke open the walls of the mental health hospital and in so doing became historically important in three aspects. First the bloco revitalized the street carnival of the neighborhood of Engenho de Dentro, secondly, it represented an alternative of cultural occupation in a poor area with few cultural institutions and with high rates of violence and thirdly, by foregrounding mental health as a protagonist of these actions and also in creating the first mental health carnival bloco in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Bringing together mental health users, family members, and employees of the public mental health network, as well as residents of the neighborhood and surrounding neighborhoods, the “bloco” created a movement toward community integration energized by Brazil’s largest popular party. Ever since the “bloco” opens Carnival celebrations for the neighborhood, drawing many “foliões” [Carnival merrymakers]. Over the years what we have seen is the transformation of prejudice against madness into admiration, respect and desire to support integration. The big annual parade through the streets of Engenho de Dentro takes place every Thursday before Carnival and is accompanied by the drum battery known as A Insandecida e Amigos [T.N. neologism of insanidade = insanity and decida = decided “decidedly insane” and Friends] and welcomes about 1000 “foliões” from all over the city. The parade is a great mobilizing force, beginning months beforehand featuring: musical workshops; the design, making and recycling of costumes; general rehearsals; creating samba compositions and the choice of Samba Enredo [T.N. an award winning samba chosen each year for the parade]; preparation of the costumes of the Bloco’s mestra-sala and porta bandeira (adult couple and child) [T.N. A key role in Carnival parades is the mestra-sala and porta bandeira, literally master of ceremonies and standard-bearer, assumed by a male and female couple in full fantasy costume who lead the parade in a dance, one showing off the other – there is generally both an adult and child couple]; the making of the year’s T-shirts and banners; organizing the reservations and loans of costumes in the Barracão [T.N. while literally meaning “barn” the Barracão is the traditional name for the large gathering places (often barn-like structures) were Samba schools create Carnival and is synonymous with multi-disciplinary creativity and collectivity]. A very singular feature of the Bloco Loucura Suburbana allows for the loan of costumes and free make-up session hours before the parade.

Over the course of its trajectory the Bloco has received various awards for its parades and its work of integration. Such as: the Prêmio Cultura e Saúde [Culture and Health Prize] awarded by the Ministries of Culture and Health (2008 &2010) twice; the Prêmio Serpentina de Ouro [Gold Serpent Award] awarded by the newspaper O Globo – in the category Highlights in 2013, and Organization in 2016; o Prêmio Ações Locais [the Local Actions Prize] conferred by the Municipal Department of Culture in 2015; and in the same year the Prêmio Cultura de Redes [the Network Culture Prize] granted by the Ministry of Culture (MINC), positively evaluating our practice of acting through partnerships and networks as apparatuses of art and culture and mental health; and most recently in 2017 the Rio de Janeiro Legislative Assembly’s Motion for Recognition for its contribution to the Anti-Asylum Struggle.

Workshops and the Ponto de Cultura Loucura Suburbana

In 2009 the Ponto de Cultura Loucura Suburbana: Engenho, Arte e Folia was created. It was the first “culture point” in mental health in the city of Rio de Janeiro and had the support of the Rio de Janeiro State Department of Culture. From then on Loucura Suburbana presented regular workshops, offering permanent activities open to the population, free of charge, that draw on the memory of samba and carnival, as well as supporting other educational, cultural and income generating initiatives, which had previously been isolated endeavors. These funds along with other financial support enabled us to hire professionals in the field of music, cultural production and fashion design. These workshops facilitated the growth and the indisputable improvement of the quality of the parades, also representing a key cultural space for both the mental health network and the neighborhoods around the hospital.

A key initiative in this process has been the Oficina Livre de Música [Free Music Workshop] that had been taking place since 2007 at the CAPS Clarice Lispector – a social assistance and psychiatric treatment center service close by to the Instituto Municipal Nise da Silveira and a partner in the creation of the Ponto de Cultura project. The musician Abel Luiz whose life story is intertwined with the neighborhood and with the institution coordinates the Oficina.4 Born and raised in Engenho de Dentro, Abel attended the sports grounds of the Nise da Silveira Institute as a child. He had begun to develop a volunteer music workshop at the CAPS Clarice Lispector, which was then incorporated into the Ponto do Cultura, when the project was started. In addition to musical composition Abel also teaches guitar and cavaquinho [T.N. a Portuguese four string instrument of the guitar and lute family of instruments]. Happening weekly, it is a permanent space that aims to give support to composers throughout the year and especially during the months leading up to Carnival. Classes turn into musical events in the form of saraus [T.N musical, poetic and performative gatherings], opening spaces for apprentices of music, composition and song.

This musical activity is one of the initiatives that has discovered the most talent over the years – many composers emerged through the encouragement of participating in the Bloco’s samba storytelling contest each year. We hold a samba school, an annual event that selects the winning samba, that receives an average of 20 competing sambas – the majority from mental health users – and, undisputedly, the quality of the compositions has improved a lot. The Loucura Suburbana archive features some sambas that have made history and are sung in all the parades and are have presented on the CD Sambas Campeões [Samba Champions] recorded in 2012. Sample some of these via the following link:

Recordings of Champion Sambas

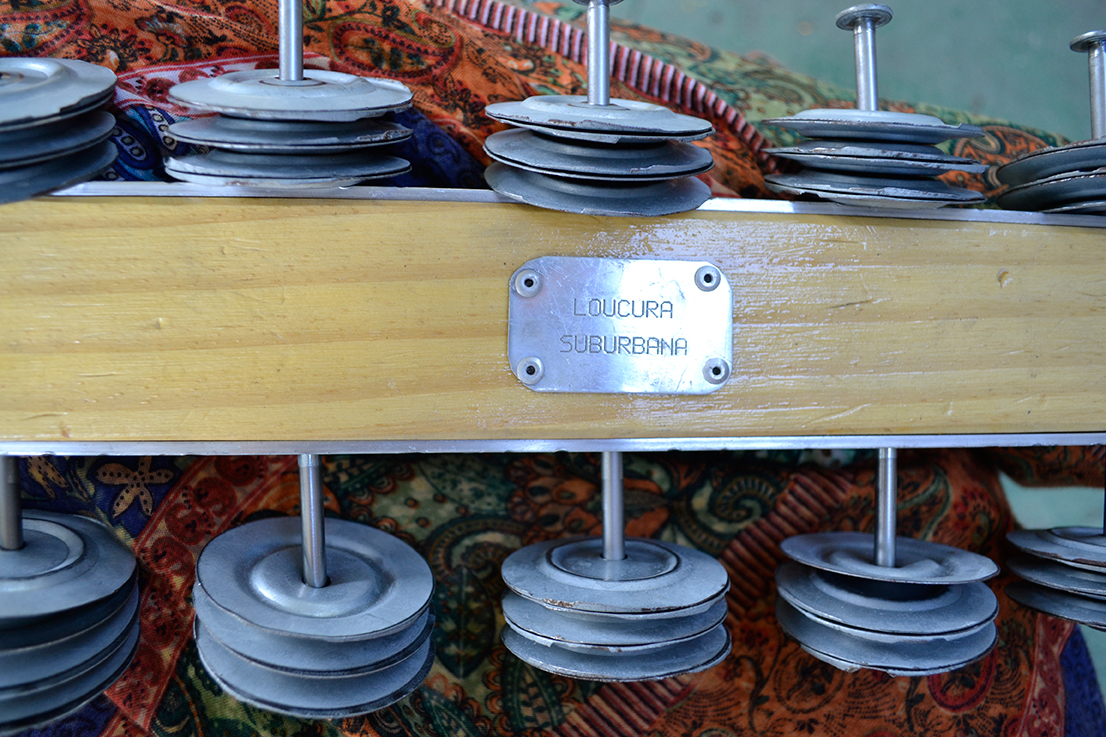

If today the Bloco has its own drum battery, Insandecida, it is only because we hired drummers and developed a persistent practice of twice-weekly lessons via the Percussion Workshop. Prior to 2011, the year of the battery’s debut, the Bloco paraded relying on the partnership of drum batteries of several Rio de Janeiro samba schools. The current master, Fernando Mesquyta, began his activities as a student of the musical workshop.

From that musical nucleus other activities emerged like the Rodas de Samba [Samba get-togethers], Oficinas de Música Itinerantes [Traveling Music Workshops] and the Encontros de Oficinas [Workshop Encounters]. The “rodas” became an important cultural occupation of a public square in the region – Rio Grande do Norte Square – contributing to the revitalization of this public space and integration with the local community. Many of the encounters featured special guests and key characters in the history of Carioca samba [T.N carioca = moniker for someone from Rio de Janerio] and at one point had bimonthly meetings. There were 25 “rodas” [T.N. rodas literally “in the round” sessions of samba are informal music gatherings with various musicians/singers]. Some took place inside the Institute and others in neighborhood bars. Unfortunately, they have not been happening for some time due to the Ponto de Cultura’s lack of resources. A number of the traveling workshops bring together members of the two musical workshops and are held one of the CAPS in the center of the city. While the Encontros de Oficinas occur monthly proposing musical artistic manifestations, film projections, and literary expressions, combining all the various workshop themes and other network services.

Another important nucleus of activities is the Ateliê de Fantasias, Adereços e Moda [Costume, Props and Fashion Studio] which is a space for the creation and recycling of costumes and the making of props for the Bloco and items for income generation and the Barracão, where more than 1000 pieces of carnival costumes and props donated by samba schools may be borrowed during the annual parade and other parades throughout the year.

Caring for Work and Citizenship

In addition to these workshops, Loucura Suburbana has created a number of other initiatives not only for art, but also for education, digital inclusion and literary expression, here embracing the importance of broader understanding of care that includes fostering citizenship and job and income generation. With these objectives and responding to a social demand, the Nise da Silveira School of Informatics and Citizenship and Encantarte Editora [Publisher] were created.

Fostering opportunities to develop citizenship and job generation are an important aspect of our work. We live in a country of inequalities dominated by an elite that does not provide access to culture and art, and those that attend public mental health services are generally poor and disadvantaged without access to culture, work, education, and health. Our work is a complex composition, not only of culture and art, but also that which, when structured with the objective of promoting the experience of work, citizenship, and social inclusion, greatly contributes to the acceptance of patients both by their families and in society. This was demonstrated by the success of the School of Informatics and Citizenship (EIC), which provided access to computers and job opportunities, training more than 600 people among these mental health users, their families, Institute employees and residents of neighborhoods close to the hospital. The project effectively promoted social integration and reversing hierarchies, as the teachers were psychiatric patients, unfortunately lasting only until 2013 when the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Health Department withdrew their support.

It was with via the mental health users trained by the EIC that the Encantarte Editora was created – another pioneering project that offered the possibility for users to express themselves through literature. Writing and publishing inaugurated another space to give meaning to their life histories and their poetic-literary talent. It also gave them professional editorial training. The users themselves are responsible for all the editorial process from writing to final publication. Currently they have more than 40 publications, most by users of the mental health network. Encantarte became a laboratory for project development and related fundraising enabling us to maintain these activities to this day. It is important to point out here that, while cultural actions have been recognized as playing an important role in the transformation process of Brazilian mental health with its objective of asylum extinction, they have not yet been incorporated into the public health budgets. So the role of Encantarte has been very important. Beginning in 2003 and officially inaugurated in 2005, Encantarte executes, in addition to the publication of books, projects and graphic pieces that publicize the carnival Bloco, the activities of the Ponto de Cultura, and events held in partnership with other organizations.

Paper-making workshop. Photo: Archive Suburban Madness

As part of Loucura’s ongoing practice of experimentation and collective construction, which can be characterized as our methodology, the Oficina do Papel [Paper Workshop] began as means to, like the Encantarte Publishing House, generate income and jobs by making stationary. In 2012 the Cyber Café was established offering free Internet access to the general public and, as part of the café, the Espaço de Leitura [Reading Room] that works with a library of about 900 volumes, donated, sanitized and cataloged by mental health users that are part of the Loucura Suburbana team.

Integration: “Who is crazy? Me or you?”5

This work to combat stigma allows people to feel happier, offering solidarity and open arms, where pathologies do not matter – no matter what the diagnosis. Our day-to-day embraces social integration, welcoming patients are part of our team. Working with us a person suffering from mental health problems can feel freer, get rid of the weight of stigma, and be more creative. Here, they can develop their potentialities in the area of the creative expression and work opportunities, one or the other, if not both, which is what often happens. There are people who work with us who are poets and who develop projects for the Ponto de Cultura.

Art, culture and income generation here come together to promote social inclusion and the exercise of citizenship. People are helped to develop their potential to in turn develop other potentialities that is the possibility of work, of being useful to society and to oneself, because people have real difficulty in surviving.

Our work is open to the general public and serves as an adjunct to therapeutic treatments, featuring innovations that promote inversions in traditional therapeutic hierarchies such as the EIC where mental health users are fully integrated into the team and see themselves as equals. There is a daily conviviality where there is a naturalization of madness, which is no longer seen as a pathological matter, but a state of being. We are there to live with it, to exchange. Opportunities are offered so that patient potentialities can be developed in various fields: in the musical field of percussion, in the creation of songs, in singing, in learning an instrument like the cavaquinho, and in the field of literature. In the latter literary workshops promote the writing of texts and the possibility to turn these into books, thus marking something very important that is the story of each one, the opportunity to tell society about their lives and what they feel and think.

In an innovative manner such practices make it possible for people to naturalize their madness within an environment that is not based in social assistance, but rather one that emphasizes openness and culture. You are not here as a patient who needs to treat yourself, you are here as a person who is equal, and who is here exchanging with the whole world what he has to give. And this serves to take away the burden, to lessen the burden of prejudice, the burden of carrying that label of the madman as a dangerous, abominable and useless human being which the popular imagination here in Brazil instills.

Through this coexistence and openness to exchange with society new identities emerge. As the stigma of madness is reduced, people feel lighter because they find solidarity, joy, receptivity, and a welcoming of who they are and their potential, so then the possibility of developing potentialities enables the production of new identities, which is key in the field of mental health. The identity of the crazy person is exchanged for that of the crazy artist (as in the time of Nise of Silveira). In this way the person already feels something else, they can say of themselves: I am a passista [T.N. Brazilian samba dancer] a writer, a painter, a standard-bearer, not for the title, but for the wealth of meaning that these activities bring in themselves.

Video with footage and interviews of the Bloco Carnavalesco Loucura Suburbana, 2012. Dir: Júlio Stotz [Portuguese only]

Retraction and Resistance

Beyond mental suffering, which already positions the individual in a context of difference and incomprehension, there are various forms of social exclusion that cumulatively make the life of a patient of the public services of the city very difficult. For example: prejudice toward madness, belonging to a sector of society in social need, living in poor conditions far from the center of the city. Exclusion is not only because of insanity – it is also a social exclusion due to the conditions of a social class with limited resources and poor quality of life.

In addition to all this, failed State and municipal systems no longer offer possibilities of daily access stipends to health services. These, often fundamental stipends, enable a patient to circulate within the city. This in turn almost promotes a return to the situation of “hospitalization” where mental health users become house bound because, without their public transport pass, they do not have the money to pay for their transport around the city. This has been a setback and has led to a decrease in attendance to cultural activities and even to care services, both by restricting free passes and because, in the crisis of mental health, many daily and integral care services (e.g. CAPS) have seen a decrease in their supplies of medicine and even food. And there are also threats of retrogression in the mental health policy by the Ministry of Health, privileging the financing of the private sector, to the detriment of the functioning models of disseminated territorial psycho-social services that are the CAPS system.

The main source of sustainability of the Bloco and Ponto de Cultura has been our ongoing participation in competitive public funding opportunities at the municipal, state and federal levels, and very rarely through sponsorship or donations from the private sector. The public health sector supports the infrastructure and a small part of the team.

Nowadays, due to the lack of cultural funding opportunities within the last two years, Loucura Suburbana is experiencing the worst crisis in its existence, not only due to the lack of resources for sustainability of the team, but also with respect to the deconstruction of the public health sector, with real effects, as I already noted above, in people’s lives. Because of all this, for the first time recently, we had to resort to collective funding to get the Bloco on the street for the 2018 parade.

Networks

Standard-bearer of Bloco Carnavalesco Loucura Suburbana Elisama Arnaud welcoming people to the poetry-music Sarau Hoje é o dia do sonho [Today is the day of the dream], October 5, 2017. Photo: Denise Adams

Our daily struggle for resources for the survival of the organization parallels the daily struggle of mental health users for survival and for a dignified life. It also shows us the path we have taken and the way we have worked since the creation of the Bloco and all other services of the Ponto de Cultura: collective construction and working in/with/through networks. We only function because we work with networks, be it the health services, the cultural facilities of the city, local commerce, or the neighbors of the territory where the Institute is based. These are the webs (connections, affections, understandings) that sustain us. And it was this work of networks that made possible the exchange with the Art_care project and its encounters Care of Method # 1 and # 2, which in turn inspired and propelled us to reestablish and fortify Instituto Municipal Nise da Silveira’s internal network of cultural services, as well as collaborate with the Museu Bispo do Rosário Arte Contemporânea of the Juliano Moreira Institute, in the production of the beautiful poetic-musical Sarau held as part of the Care as Method # 2 encounter.6

The very resistance of Loucura Suburbana, recognizing our force and ability to cope with the difficulties that constantly threaten our very survival and capacity to reinvent ourselves, nevertheless bring its own stability. There are signs that this has been recognized by the Municipal Health Department and this gives us the hope of establishing negotiations via the Instituto Nise da Silveira to ensure that the culture is even more contemplated in its mental health policy, in concrete form, through the financing of part or all of the project.

The Bloco, as well as the Ponto de Cultura Loucura Suburbana remain active, mainly due to the great dedication of its participants, both users of the public mental health system, the community, and even general public who volunteer in various capacities and have not only provided a means to keep the initiative alive, but also avenues to increase its work.

This daily struggle for survival is very harrowing and very tiring as well. Sometimes we do not see possibilities for resources in the short term, but we trust in the work and in each other, and this is what has given us the strength to date, to overcome the really difficult periods we have been through many times. And so we keep going! And as our master drummer says, “let’s get going”!

***

Ariadne Moura Mendes

Ariadne is a psychologist and specialist in public health and also holds a health education specialization from Fiocruz. She coordinates the Carnival Bloco and organization Loucura Suburbana. She has worked in the field of psychology and mental health for more than thirty years including posts as professor of psychology at Celso Lisboa University (1977) and psychologist at the Ministry of Health in the following sectors: National Mental Health Division (1982), Colônia Juliano Moreira (1988), Head of Planning Nucleus (1989), and Outpatient Clinic at the Pedro II Psychiatric Center (1989). From 2002 – 2009 she was consultant to the director’s office at the Nise da Silveira Municipal Institute. In addition to coordinating the Carnival Bloco she also oversees the Nise da Silveira School of Informatics and Citizenship and the publishing unit EncantArte (since 2002).

______

1 “Vamo que vamo” is a popular expression that suggests the determination to keep going without giving up in the face of difficulty. T.N. “Let’s keep going” or “let’s get going” or “let’s go for it” are all possible English translation.

2 Thankfully today this asylum in the city of Paracambi, in the state of Rio de Janeiro was closed as part of an intervention of the State Public Health Department and Municipal Health Department of Paracambi.

3 Ambulatório Central [Central Outreach Clinic] was created in 1984 bringing together various clinical outposts that had been established in the various hospital wards with the goal of offering clinical appointments to the adult population and becoming the entry point for patients into the institution with the simultaneous goal of trying to avoid hospitalizations over long periods.

4 [Editors Note E.N.] See the essay of Abel Luz in this issue [link]

5 The sentence if from the Samba Loucura Cultural by André Cabral and Elisama Arnaud, winner of the Samba School competition in 2016.

6 [E.N.] For more information on the Sarau see the photo essay by Denise Adams, vídeo by Pamela Perez and text by Izabela Pucu in this issue [link]