Euan & Jim: Sensory Workshop, 2017. Photo: Steve Hollingsworth

One of us. One of us: Finding Equality Within Difference

Alison Stirling

I have a distant memory of walking up a steep hill towards a large dilapidated hospital.1 I think I am around eight-years-old. My memory becomes foggy. Shifts. I’m in a large room, lined with what appears to be small cages on legs. I’ve come in from the sunlight and the room is dark. My eyes acclimatize and I see that there are children about my age with twisted bodies lying in these cages. I move from cage to cage, leaning in to touch a hand, a face to offer some form of comfort, to all of us.

The cages were actually hospital beds with the bed rails pulled up. From the perspective of a small child, looking up at the children as they pushed their hands through the rails, the beds looked like cages.

It’s 2016 and I’m in Rio, on the grounds of a psychiatric hospital. A man in dirty clothing staggers towards me with a tattered doll in his hand. His elderly mother is not far behind him. He extends his arms, enveloping me in a cuddle. His mother smiles.

I’m in Glasgow. This is an enduring memory, from 45 years ago, eight years ago, five days ago, yesterday. Across from me sits a woman in a wheelchair. Her hand is in her mouth, her body leaning to the side. She is rocking, lost in the rhythm of her movement. She giggles. She reaches out. We hold hands. Between us there is no difference.2

In caring, my being with the other person is bound up with being for him as well; I am for him in his striving to grow and be himself. I experience him as existing on the ‘same level’ as I do. I neither condescend to him (look down on him, place him beneath me) nor idolise him (look up at him, place him above me). Rather, we exist on a level of equality.3

Care is not something that exists in isolation, it is not something that happens to someone else and as such we need to look at care and caring with a more open mind, as something we all inevitably have in common.

Within caring environments, such as elderly care homes and units for people with learning disabilities/mental health issues etc, respecting the many different lived experiences, listening and learning from each other can fashion much needed change in how care is provided. Here, art can be a powerful tool, creating ‘a space’ devoid of hierarchies, in which all involved work towards a combined creative goal, merging experience, art and knowledge to build a new and more relevant understanding of ourselves and each other.

Art is…a genuinely human medium for revolutionary change in the sense completing the transformation from a sick world to a healthy one.4

Artlink is an arts organisation based in Scotland. Over the last thirty years its practice has evolved in response to the needs of service users, care providers, and the ever-changing political and social climate of the United Kingdom. Artlink works within systems of care, in collaboration with individuals with profound cognitive disabilities, and enduring mental ill health. Despite the efforts of care providers and institutions, many of these individuals are marginalised, their voices overshadowed by the complexity of the care they require. 5 In addition, for those who care, the low status afforded their vocation often results in poor pay and stressful working conditions.

Artlink supports a diversity of arts programming within care institutions and communities, ranging from long-term collaborative projects, to single events and weekly workshops. In 2010, Artlink launched The Ideas Team to explore the use of contemporary arts practice to address the specific needs of people with profound cognitive disabilities. The Ideas Team is based at Cherry Road Centre, a publicly run day centre for adults with complex developmental, cognitive disabilities and autism.6

Fig 1. Staff Training by Miriam Walsh – Who Do You Think You Work With? 2014. Photo: Alison Stirling

Fig 2. Staff Training by Steve Hollingsworth. 2018. Photo: Steve Hollingsworth

The aim of the Ideas Team was to challenge hierarchies within care services for people with profound cognitive disabilities and search for solutions outside of traditional care and therapeutic models. We sought to establish a more level ‘playing field’ where those who care and are cared for are respected and valued for their knowledge and lived experience.

Typically an Ideas Team is led by an artist, a care staff member and family member working closely with the person with profound cognitive disabilities. Together they identify a goal, something simple and achievable that they can work together to solve – for example, identifying what captures an individual’s attention and encourages them to sit and concentrate for longer than a minute.

In the past as ideas have formed, the ‘team’ has opened up to include psychologists, engineers, anyone and everyone who to provide very different answers to questions arising from this new learning.

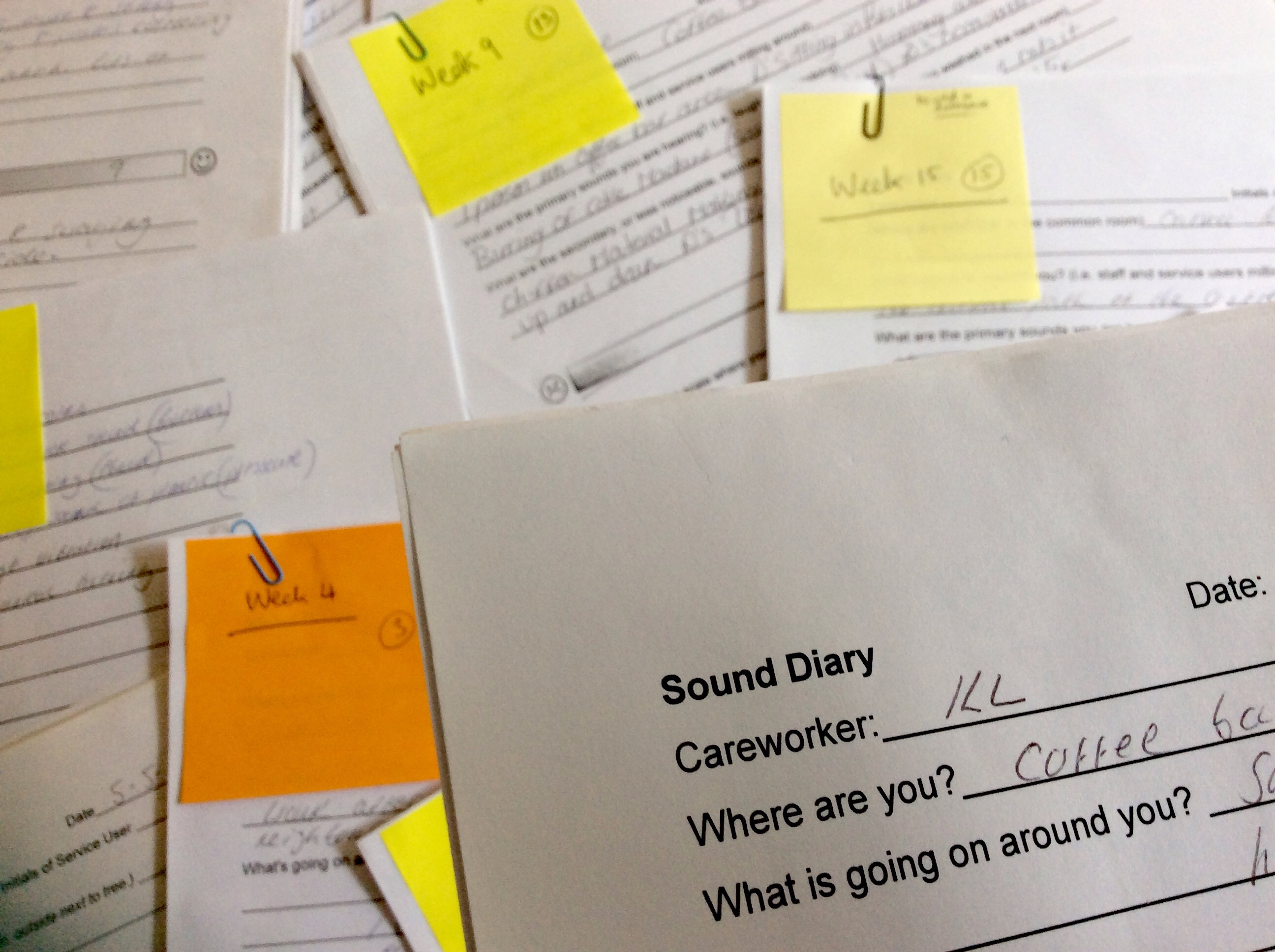

The world of the individual with complex cognitive disabilities is often dictated by the people who care for them, with almost every aspect of their lives determined by someone else, such as what activities they get involved in, where they sit, when they eat and sleep etc. From the beginning our main problem was not how to involve the individual with profound cognitive disabilities but how to involve the over-worked care workers that supported them. As without one we could not properly involve the other. Firstly, we had to alter their preconceptions of art and open their eyes to the role creative thinking could play in forming a greater insight into the person they worked with. We began with a series of (ongoing) training events that allowed care workers to take on different perspectives, for example: we encouraged care workers to slow down their actions and voices to allow those they cared for to better take in what was happening around them; we put on relaxation classes which allowed staff to get lost in the moment; we created sound diaries where care staff described the detail of the sounds that surrounded the person they worked with.

Artists worked with the individual slowly introducing new sensory based experiences, all the while including the care worker in order that they could observe and discuss the tiniest interactions, looking for the moment when a real connection is made.

Fig 3. Sensory Diaries – Wendy Jacob, 2015. Photo: Miriam Walsh

Fig 4. Playing With Detail – Fiona, Fran & Kevin 2015. Photo: Kevin Hutchison McPhee

The more they learned from the individual, the more it informed the training we gave to care staff. Very slowly change began to happen. Change in how they all perceived ability; change in confidence; change in self worth; change in relationships between all involved informing a growing respect for each other’s ways of being.

The Ideas Team became a space for collaboration and creative experimentation, developing new work in response to this new learning, one that now spans years.

The individuals’ independent enjoyment was found within the detail of sensory actions and interactions – i.e. the sensation of scratching a finger nail on a wheelchair arm, of a whisper, of the intensity of light cast on the back of a hand. As confidence grew, the artists had a greater freedom to explore these details and nuances with the individual, entering into sensory worlds that communicated a new and very different understanding of each person – eg one young man was viewed as “unable to learn.” With the artist working closely with him, trying new ideas, talking with his care workers and family, working with engineers, the young man over time began to navigate his way around an installation built for him, using a joy stick to move around and through sound-sensitive images. Over time his interpretation of his physical movements became more focussed, it became clear he was communicating an identity that went far beyond limited preconceptions of his abilities. Understanding of actual abilities began to change.

Fig 5. Sensory Workshops with Lauren Gault, Laura Aldridge, Laura Spring. Photo Laura Spring

The act of taking the time to collate these details becomes emancipatory for the individual, their carers and the artists. For the carers, purpose is created where dull routine previously existed. For the individual, a greater sense of identity is formed when actions and reactions are understood and respected. For the artist new perspectives inform unique arts practices. For all, difference is learned from and valued.

As Liz Davidson7, Cherry Road Centre manager puts it: “it’s an exploration of human relationships built upon mutual trust and equality. All parties involved are learning and exploring their environment and sensory world, listening and observing together for the first time.”8

We have found that by opening up alternative conversations around detail no matter how small and seemingly insignificant, we expose new possibilities. Being given the space and the time to think creatively, to listen to and understand each other’s perspectives, encourages curiosity and from that, new learning.

You learn about someone in an unconventional way as exchange and communication is often through other means than spoken word, so the slightest gesture can become of great significance. It is often about working instinctively and Artlink allows for the time and space for this to develop that isn’t always possible in other areas of life for the people we work with.9

This is not something that happens overnight. To consolidate any change within these complex environments means that relationships and artwork have to be realized within slow time. Artist, Wendy Jacob puts it best in her description of working in Cherry Road Day Centre: “Time is understood very differently here. Progress is measured in minute increments. Moving quickly is not possible. In order to do anything meaningful in this context, it is critical to have time for ideas to slowly incubate and develop.”10

Through slowing down time, we are discovering new vocabularies that don’t involve words or symbols. Quite simply, the act of working together has formed its own communication, releasing people to use their imaginations and work in ways that they have never tried before. This new “language” talks of a radically different view of the world, one that we are only just beginning to understand.

We began to establish our own sensory vocabulary, it became our lingua franca […] People with (complex disabilities) are perfectly capable of learning new experiences if they are given the time and are motivated through sustained interactions. Ben has rewritten his personal narrative and those around him see him in a more positive light.11

Fig 6. Light experimentation with Natalie, Wednesday Sensory Workshop2017 (Lauren and Natalie). Photo: Lauren Gault

Fig 7. Light experimentation with Natalie 2017.Photo: Lauren Gault

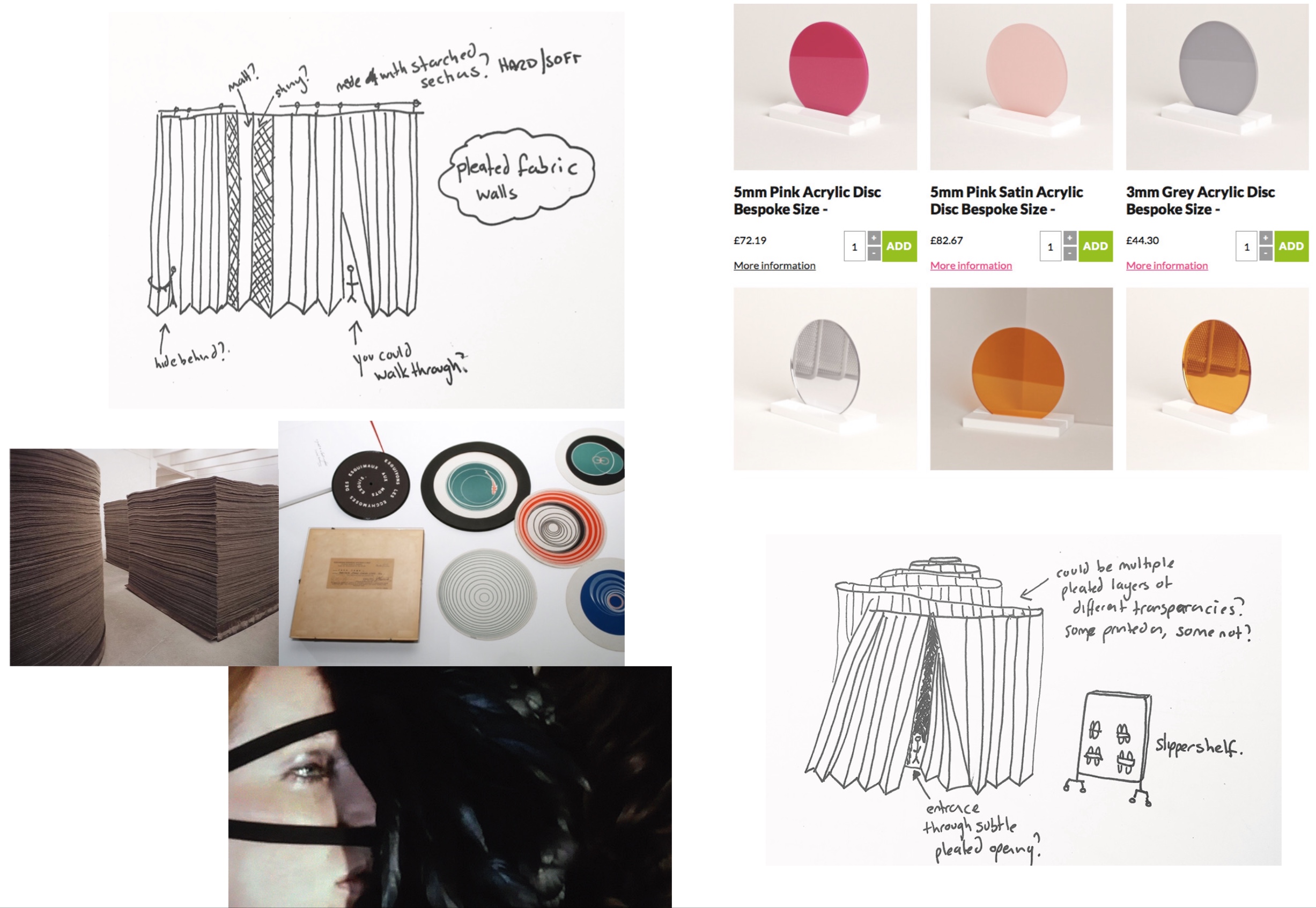

The learning emerging from this work will be taken onto a very different stage. A large scale exhibition planned for Spring 2020. This will challenge us to extend the work to a wider audience all the time ensuring the continued involvement of people with profound cognitive disabilities. Artists from Scotland and USA will work with different sensory ways of being, creating artworks into which audiences will be immersed. Our intention being to “integrate” audiences, bringing people with complex cognitive disabilities together with people from all walks of life. We want to create a place of many delights and intimate perceptions, in which everyone is equal, where the sensation of being in a space and interacting with it becomes an “every body” experience.

To achieve this, the work will be shown in an entirely different way, stemming from the very particular ways of being of the individual with complex cognitive disabilities. What results will a place of freedom, of quiet, touch, sound, light, vibration. It will be a place where the physical experience of the artwork is a language shared – the culmination of over thirty years of work.

There is much we can learn from the experiences of the most marginalized members of our society. Firstly we must free ourselves from the distinction of “us and them.” If a society is ultimately judged by how it treats its most vulnerable, then it is imperative that we take the time to look for equality in our differences and join forces, as together we have a much louder voice.

Fig 8. Ben, 2017. Photo: Steve Hollingsworth

After all.

We are the woman in the wheelchair.

We are the man in the hospital grounds and the children in the beds.

They are us.

We are them.

One of us!! One of us!!12

Fig 9. Study for exhibition. 2018. Image: Adam Putnam

Fig 10. Study for exhibition. 2018. Image: Laura Aldridge

Fig 11. Study for exhibition. 2018. Image: Claire Barclay & Laura Spring

***

Alison Stirling

Studied at Glasgow School of Art and the Royal College of Art, London. As artistic director of Artlink, she has created innovative projects in the public sector for over 24 years. Her current focus is arts practice within The Ideas Team (Artlink initiative) that will culminate in a large-scale exhibition in 2020. This ongoing work aims to draw attention to and change preconceptions of and ways of caring for, some of the most marginalized in our community.

__________

1 Craigrownie Castle was donated to the Scottish Society for the Mentally Handicapped (SSMH now Enable) by Miss Ella Stewart and became the Stewart Home for children from 1958 until 1983, Scotland’s first short-stay home for children with learning disabilities. The particular ward I visited as a child, as part of an annual family trip run by SSMH, was for children with profound physical and learning disabilities.

2 The woman is my sister.

3 Milton Mayeroff, On Caring: Caring for Other People (London, Evanston, New York, San Francisco: Harper & Row. 1971) 31.

4 Joseph Beuys. In: Quartetto. Joseph Beuys, Enzo Cucchi, Luciano Fabro, Bruce Nauman (exhibition catalogue) edited by Achille Bonita Oliva (Milan: Arnoldo Mondadori, 1984) 106.

5 The advances made in services for the wider group (people with physical or sensory disabilities) have often failed to benefit this minority group (people with complex disabilities) who are typified by powerlessness and low status with their families and staff often sharing in this lack of power people and status. Kieron Sheehy & Melanie Nind “Emotional Well-Being For All: mental health & people with profound & multiple learning disabilities,” British Journal of Learning Disabilities (London: BILD, 2005) 35.

6 Cherry Learning Centre offers tailored and personalized experiences supporting adults with learning disabilities and adults with autism. Formerly based on a more traditional model of care, the service recast itself in collaboration with leading arts and disabilities organization, Artlink. This enabled the service to develop imaginative and enriching experiences for people and has significantly improved how the service supports people with very complex needs, leading to sustained positive change and contributing to reduced use of health and care services.

7 Without open and creative management at Cherry Road day centre none of this work would be possible. They have worked in partnership with us throughout the Ideas Team project.

8 Liz Davidson. Presentation as part of Edinburgh University Disability Research Group. The Ideas Team blog, November 2015 https://ideasteam.org/2015/11/13/liz-davidson-day-centre-managerpresentation-as-part-of-edinburgh-university-disabilty-research-group-november-2015/ [Accessed March 5th, 2018]

9 Laura Spring. Artist Laura Spring on her Artlink Practice. The Ideas Team blog, August, 2015 https://ideasteam.org/2015/08/20/artist-laura-spring-on-her-artlink-practice/ [Accessed March 5th, 2018]

10 Kirsten Lloyd. Uncommon Ground: Radical Approaches to Artistic Practice (Edinburgh: Artlink, 2016) 16-17.

11Joanna Grace. Sensory-Being for Sensory Beings: Creating Entrancing Sensory Experiences (London: Taylor Francis Ltd., 2017) 33-34.

12 In Tod Browning’s Freaks, made in 1932, circus performers join ranks chanting “one of us, one of us” as a show of acceptance of the “normal” outsider. As a young adult watching this film I was drawn to the idea that difference could draw us together. That we were in fact all the same. Unfortunately their camaraderie is short lived descending quickly into different camps, bullying and power struggles. The chant in this spectacularly un-politically correct movie still resonates today, as sadly do the separatist attitudes it ultimately portrays.