Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle, Seven Thousand Cords (After Beuys), 2014, SAIC Sullivan Galleries. Photo: Tony Favarula

Living Chicago Histories

Mary Jane Jacob

In this issue, at the invitation of Jessica Gogan and Luiz Guilherme Vergara, we are endeavoring to represent the experience of a program on social practice in Chicago called A Lived Practice. It is true that the web can only capture images of art and times past. It lacks the emotion, the real experience, we have in the presence of art and of being together which, to philosopher John Dewey’s mind, can be transformative. Such experiences enlarge our world and have the potential to bring others’ experiences into our own. In fact, for Dewey, art was the experience, not the objects or actions but what those things cause in us. So while this issue is a shadow of the real experience of the exhibition and programming curated by Kate Zeller and myself, we hope it can afford another experience.

Our research concerned socially engaged art practice and particularly why it is such an important mode of working in Chicago today. For Dan Peterman, who came to figure into the exhibition, Chicago art is “not just to represent culture, but to afford the possibility for culture in which art could be more of a social force.”1 For another artist in the show, Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle, “Chicago becomes your conscience. Practice has a particular meaning here…beyond yourself, the object, and career.”2

As we proceeded, Dewey (1859 – 1952) and his comrade-in-arms the settlement house founder Jane Addams (1869 – 1935) became historical touchstones. They are widely respected among artists and activists here, who are inspired by their sense of personal mission. Dewey and Addams’s Chicago was a modern behemoth whose population was suffering under the weight of industrial capitalism. They sought to forge this city into a modern society according to principles of equality and justice, making Chicago a model of social change for the world. Our process is one of dialogue with artists and we found that the artists we worked with shared these values. Bound by intention, they appreciated Dewey’s thought that “the clear consciousness of a communal life, in all its implications constitutes the idea of democracy.”3 And this notion gave rise to the exhibition title A Proximity of Consciousness: Art and Social Action.

Morgan Puett, HumanUfactorY(ng) Workstyles: The Motion Journals of Excerpts from the User’s Guide to Mildred’s Lane.

A costume drama of the everyday, 2014, SAIC Sullivan Galleries. Photo: Tony Favarula

In this exhibition we wanted to capture how artists live social practice now — how their research, making and being are one. Kate Zeller’s contribution here seeks to convey the vitality of their work and the many programs that took place around it, that is, the ways in which artists and community members lived the exhibition while on view. And in looking to the work of Dewey and Addams at the end of the 19th century, we also wanted to see what role Chicago’s history played in the evolution of the art that today we call social practice.

Morgan Puett, HumanUfactorY(ng) Workstyles, with replica of Jane Addam’s desk at the Hull-House, 2014, SAIC Sullivan Galleries. Photo: Tony Favarula

Our process of working and locating meaning took many forms. One was the Chicago Social Club, a casual enough convening that also served as a critical think-tank for local practitioners to come together over two years and, while hearing from artists, designers and curators about their projects, share space around questions of practice. I am pleased to say that Gogan and Vergara where there among the presenter-interlocutors. We also questioned, was an exhibition enough? We knew — from experience — that there had been times we had left exhibitions saying, “That show would have been better as a book.” So we pondered the need for a book that told a larger history than an exhibition could – and yet would still be a living experience — and tested this idea with four individuals in Chicago’s art community: Abigail Satinsky, Stephanie Smith, Daniel Tucker, and Rebecca Zorach. In them we quickly found a team of editors and together launched into a yearlong exchange, thinking through decades, protagonists and issues from the 1880s to now, looking at the many ways artists have worked to make change and make life better for themselves and others.

We had also observed in the field a growing international community around social practice that hungered for new tools. Some sought dialogue and solidarity to press forward; some searched for precedents to understand from where this work sprang so that it might not be taken as a passing art style. In expanding the discourse, books and on-line magazines like this one played a big part. But we also wanted to open up the discourse of social practice so that it could be seen as a rooted, sustained and necessary way in which art and society have connected over time. The resulting project — the Chicago Social Practice History Series — offers a deep contextual understanding for social practice as place-based work through an in-depth, sited study of Chicago. These five volumes became a cornerstone of A Lived Practice program.

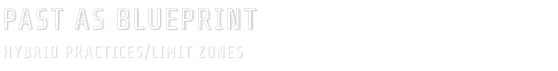

Since our story was Chicago, we needed to paint a picture of the city. Knowing there is no single Chicago, Institutions and Imaginaries, guest edited by Stephanie Smith, takes us to some idiosyncratic spaces within the city’s institutions as well as in the minds of writers — for imaginaries have the power to shape place as much or more than the built environment.

Institutions and Imaginaries. Cover from the Chicago Social Practice History Series. Design: Corey Margulis

Chicago was an act of invention: a city made out of whole cloth in the American way. In that early period Addams and Dewey were institution builders. Her Hull-House, founded 1889, provided refuge and resources of all kinds to an emerging American population that had experienced a rupture from their cultural past, along with the ravages the industrial revolution played on them and their families. His Laboratory School at the University of Chicago, founded 1896, sought to model education as child-centered learning by doing, seeking to set standards for the nation and leading the way for future thinker-practioners like Paulo Freire. At the turn of the 20th century when Dewey and Addams were venturing into their boldest undertakings, modern sociology was among the inventions they spawned, too. Their reforms of the educational and criminal justice systems, along with championing workers’, children’s, and women’s rights, were also their brand of institution-building here. Importantly, in all of this they believed in the power of art to make personal and social change. Both Addams and Dewey saw art as essential to a life well lived, a way we deepen the consciousness of ourselves and the world around us, practice empathy for others and, by cultivating imagination through art, imagine a better way.

The founding of Chicago’s museums, libraries, universities, and public schools were part of the new society they imagined, but today there is a wider ecology that extends beyond the so-called major cultural and educational institutions and which, like the clubs, associations and activities that Addams and Dewey piloted, include independent projects and artist-run initiatives. In Chicago the art world has always been about association, some formally named, others ready to access when a call is made or to find faith in by just knowing they are out there. This is the possibility of community that can come about through a supportive network.

Support Networks guest edited by Abigail Satinsky takes up this story of artists’ agency, looking at the mechanisms they have employed to realize a community of practice. It expresses the human story behind why we make art, what showing art affords to a communal dialogue, and why sharing art with a non-art-going audience matters. In many ways the same needs that gave rise to Dewey’s ideas remain present. In her introduction to the book, Satinsky evokes John Dewey’s understanding of community as simultaneously a democratic way of being and a way of continually enacting democracy. This thought finds relevance in Chicago’s social and artistic alliances today. In all the instances one encounters in this volume, the reader senses the protagonists’ drive as they live the values of diversity, equity and social justice that they hold dear. These run deep, finding their lineage in Addams and Dewey’s experiments, and like them, artists still weather tough processes to achieve their ends. Hence their purpose needs to be clear and bigger than themselves.

Support Networks. Cover from the Chicago Social Practice History Series. Design: Corey Margulis

This was the personal experience of Satinsky, who as Addams before her found like-minded doers and thinkers in Chicago, in her case, in the classroom as a student at the School of the Art Institute. In 2007, as part of a cohort of emerging arts administrators, she formed InCUBATE (the Institute for Community Understanding Between Art and the Everyday) to rethink how fundraising might operate if approached creatively. Their Sunday Soup project, a reinterpretation of the soup kitchen of Addams and Dewey’s era, has taken off with more than 60 versions worldwide.

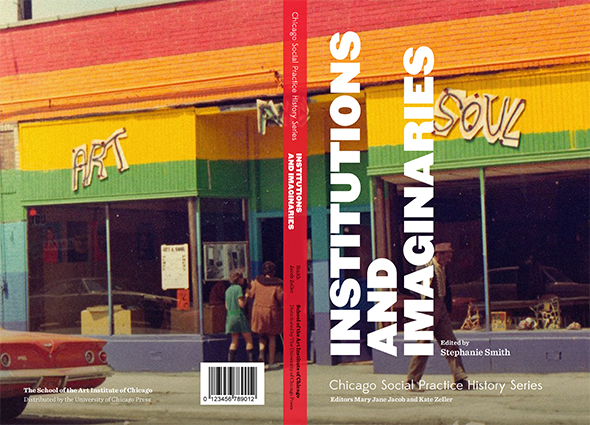

It might seem an anomaly, a deviation in its specificity, to have devoted another volume to the subject of Art Against the Law, which guest editor Rebecca Zorach put forth. It might make one wonder if there is something very “Chicago” about the subject? Or is this just a condition of our cities? John Dewey saw it in his time when he wrote in The Public and Its Problems (1927): “The same forces which have brought about the forms of democratic government, general suffrage, executives and legislators chosen by majority vote, have also brought about conditions which halt the social and humane ideals that demand the utilization of government as the genuine instrumentality of an inclusive and fraternally associated public.”4 As a perpetual social condition, Dewey would remind us that it is a continual responsibility of citizens in a democracy to challenge and correct the law and to preserve social and humane ideals. Artists, as citizens and as art makers, do just that.

Art Against the Law. Cover from the Chicago Social Practice History Series. Design: Corey Margulis

Art, law, justice, resistance, restitution, and reconciliation are all aspects intertwined in this dense and deeply impassioned volume. As a historical subject, we see it in such struggles as the 1886 Haymarket Riot, an event whose reverberations for workers’ rights live on in May Day commemorations abroad, while in the US the law distances its citizens from that moment by marking Labor Day in September. Law as an art subject finds artists working in prisons, instituting programs by which they and the incarcerated can interact, using these initiatives to further public awareness, and using the penal system for beneficial and not just punitive ends. And as Kate Zeller tells the story here, art and the law permeated A Lived Practice — from Laurie Jo Reynolds and Tamms Year Ten’s in the exhibition A Proximity of Consciousness to Lucky Pierre’s Final Meal at the Hull-House Museum Residents’ Dining Hall.

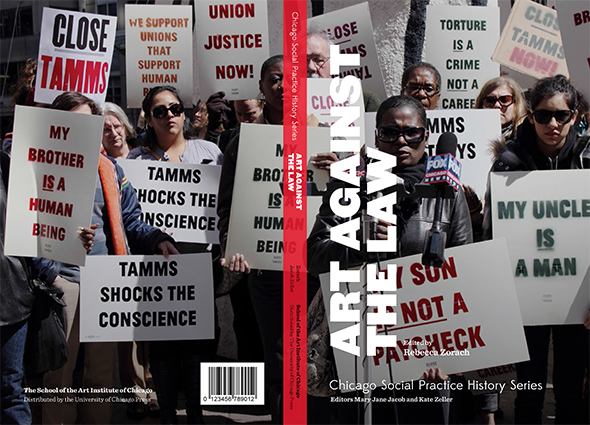

Finally, there was Immersive Life Practices, the volume proposed and undertaken by Daniel Tucker. It moves in and out of the geography of Chicago to speak of the depth of what it is to live one’s practice. How can an artist live their art when art is a life practice? Can life be an art practice for the rest of us? And if art is a social practice, isn’t life a social practice, too? These notions are wrapped up in John Dewey’s passionate mission for art as a way to achieve a life fully lived. Moreover, these questions became research meditations leading to the symposium A Lived Practice. With this effort we sought to inject some other thinkers into today’s theoretical discourse and praxis of socially engaged art practice: Lewis Hyde, Crispin Sartwell, Ken Dunn, Alistair Hudson, Wolfgang Zumdick, and Ernesto Pujol. Most of all, with the concept of “a lived practice,” we sought to engender an understanding of social practice as a way of being in the world.

Immersive Life Practices. Cover from the Chicago Social Practice History Series. Design: Corey Margulis

We live in and through experience. In the works artists create they enliven the experience of others, enabling them to find meaning — at least that’s how Dewey saw it. But to engage fully, we need to possess an open, creative mind, Dewey believed. With this symposium, being together over the course of three days, we sought to cultivate an open space in which those present might give themselves to the experience of thinking anew. To spur this on and catalyze reflection, we asked the lead speakers to help us unframe just what is art and who is the artist, while probing essential questions around the individual’s relationship to society. The vitality of the speakers’ ideas caused us to bring their ideas forward as a concluding volume and the last chapter in this Chicago project, A Lived Practice.

_

1 Artist in conversation with MJJ and KZ, summer 2013.

2 Ibid.

3 John Dewey, The Public and Its Problems (New York: H. Holt and Company, 1927): 328.

4 Dewey: 109.