Cultural Action “El pueblo tiene arte con Allende,” Salvador Allende Presidential Campaign, 1969. Photo: Luis Poirot. Fundación Salvador Allende archive collection.

An Unprecedented History: Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende1

Claudia Zaldivar

The Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (Salvador Allende Museum of Solidarity – MSSA) was an unprecedented cultural and political gesture both in its historical beginnings and its philosophy. It is atypical when compared with other types of museums in that it was fundamentally motivated based on political policies and ideas, not however, in a partisan manner.

The museum’s evolutionary process has been shaped by the history of governance in Chile and the political and ideological currents that marked the world in the last 40 years. The museum carries the history of a country inserted into an international context and, above all, is a space of/for political art in the broadest sense.

Formation of the Museo de la Solidaridad

The idea of creating the Museo de la Solidaridad was born in the course of what was called Operación Verdad (Operation Truth, Santiago, March 1971) just a few months after the government of the Unidad Popular took power. President Salvador Allende invited different international figures – intellectuals, journalists and artists – to observe the transformations that the country was experiencing in the “Chilean road to socialism.” The Spanish art critic José María Moreno Galván and the Italian senator Carlo Levi, among others, participated, proposing the initiative as a means of promoting within European artistic circles donations of artworks that would allow the Allende government to create a museum for the people of Chile and in this way, coordinate a united mobilization of the world’s artists to express their support for this political process.

Mario Pedrosa, a leading Brazilian art critic and organizer of two São Paulo biennials (1953 and 1961) was appointed Chairman of the Executive Committee of this initiative and became the main administrator and founder of the Museo de la Solidaridad. Pedrosa, who was exiled in Chile because of the Brazilian dictatorship, was well suited to lead this project, a renowned expert in visual arts who had diverse contacts with prominent figures in the international art world. The Uruguayan filmmaker and consultant to UNESCO’s Department of Fine Arts Danilo Trelles, also residing in Chile at the time, was named as executive secretary.

At the end of 1971 the International Committee of Artistic Solidarity with Chile (CISAC) was formed comprising leading artists, art critics and museum directors from different European and American capitals: Louis Aragon, French poet and director of Lettres Françaises; Carlo Levi, senator, Italian painter and writer; Jean Leymarie, director of the Museum of Modern Art of Paris; Giulio Carlo Argan, former president of the International Association of Art Critics; Edward Wilde, director of the Modern Art Museum of Amsterdam; Dore Ashton, critic of American art; Sir Roland Penrose, English art critic; Harald Szeemann, artistic director of Documenta V; Rafael Alberti, Spanish poet; José María Moreno Galván, critic of Spanish art; Aldo Pellegrini, writer and critic of Argentine art; Juliusz Starzynski, professor and critic of Polish art; Mariano Rodríguez, painter and deputy director of the Casa de las Americas in Cuba; Mario Pedrosa, also vice president of the International Association of Art Critics; and Danilo Trelles. In all 12 countries were represented on the committee: Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, Spain, United States, France, Holland, England, Italy, Poland, Switzerland, and Uruguay.

Pedrosa discussed the formation of CISAC noting that, “our first resolution was that the committee should be composed entirely of foreign personalities. Donations were to serve to organize a new museum in a new Chile. So the spontaneity of the idea of solidarity was highlighted. Danilo Trelles and I, not being Chilean nationals and living in Chile, immediately formed the core of the committee. Without delay we made several international calls to relevant art world figures to invite them to be part of the committee. We received the enthusiastic support of those who are today committee members.”2

The objectives of CISAC were to promote the idea in respective committee member countries and make contact with artists around the world so that they would support the political experience that Chile was going through and collaborate by donating their works for the creation of a museum in Chile.

At the same time, President Allende appointed Miguel Rojas Mix, director of the Instituto de Arte Latinoamericano (IAL – Institute of Latin American Art), and José Balmes, director of the Escuela de Bellas Artes (School of Fine Arts) – both affiliated institutions of the Universidad de Chile – as Chilean coordinators of the Movimento de Solidaridad Artística (Artistic Solidarity Movement) with Chile. The IAL was the center that housed the executive committee and also operated as the administrative entity of the museum until it was legally constituted. In turn, the Departamento Cultural de la Presidencia de la Secretaría General de Gobierno (Cultural Department of the Presidency of the Governmental Secretary General), through Miria Contreras, coordinated the transfer of the works to Chile, together with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The members of CISAC worked hard in their respective countries and called upon a very representative selection of artists to commit themselves to this solidarity work on behalf of Chile, which was seen as a unique case in the history of the contemporary world. The idea took shape, spreading very quickly in the art world, and a lot of people joined in the project. Pedrosa contacted most of the personalities engaged in art movements around the world, achieving the commitment of important artists.

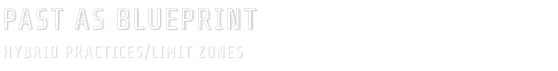

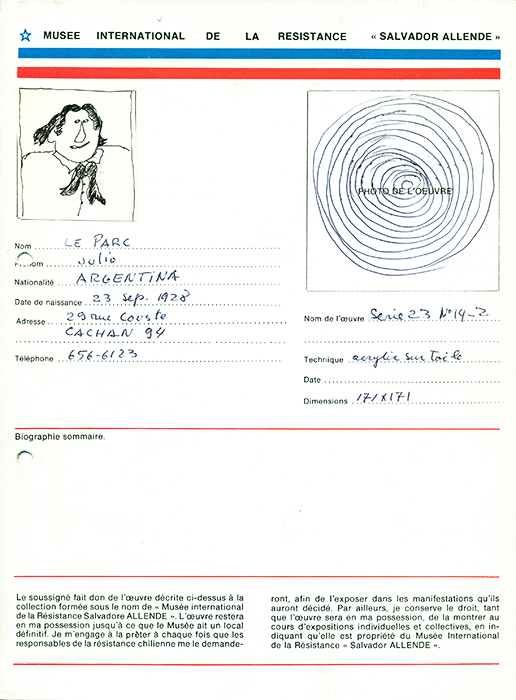

Donation forms of Latin American artists in France. MSSA archive collection.

In a very short space of time, the project was organized and implemented. “The response to the call was fabulous,” noted Pedrosa. “(…) Letters and telegrams arrive daily offering more paintings and sculptures. In some countries it was necessary to make a preliminary selection of works in order to send the best to Chile.”3

In early 1972, the first shipments were received coming from France, Spain and Mexico.4 Among them, the work of Joan Miró, who, especially for the Government of Chile, made an oil painting that represented the cock of victory.

Joan Miró, Sin título (Untitled), 1972, oil on canvas, 130 x 195 cm. Photo: courtesy MSSA. © Successió Miró/ AUTVIS, Brasil, 2015.

The works were usually sent to Chile by the Chilean embassies, via diplomatic pouch, and received by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but, at other times, they entered through customs, or the artists personally sent them directly to IAL or through acquaintances who were travelling to Chile.

Most of the time the works lacked their gift certificates, which became a problem for the legalization of the museum in the 1970s and later in the 1990s, with the return to democracy. Inventories made in Chile were just basic lists, which to date has hindered the documentation of the works.

On May 17, 1972, the official inauguration of the museum was held at the Museo de Arte Contemporaneo (Museum of Contemporary Art) at Quinta Normal, in conjunction with the Encuentro de Artistas Plasticas del Cono Sur (Meeting of Visual Artists of the Southern Cone) organized by IAL. The event was led by President Allende, who in his speech noted: “The artists around the world know how to interpret this profound Chilean-style sense of struggle for national liberation and in a unique gesture in cultural history, decided to spontaneously offer their art as a gift for a magnificent collection of masterpieces to the delight of citizens from a distant country that otherwise would hardly have access to these works. How not to feel, along with a deep emotion and profound gratitude, that we are taking on a solemn commitment, the obligation to respond to this solidarity?”5

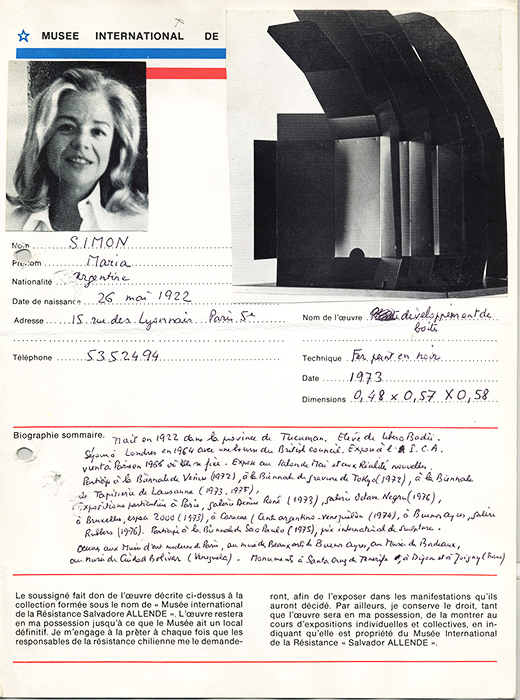

La Nación, May 18, 1972. MSSA archive collection.

In the months after the inauguration new shipments continued to arrive from France, Poland, Cuba, Argentina, Uruguay, United States, Ecuador, Spain, Mexico, Italy, and Brazil.

The Museo de la Solidaridad was nourished by the great ideological adhesion of the artists around the world to the Chilean socio-political process at the time. That’s why MSSA needed to break with traditional notions of the museum, evident in its visionary conception: to belong to the state but to be autonomous; and because of its objective and unique philosophy it could therefore not act as an expansion to the art collection of another institution. In addition, the museum would have to remain as an independent entity with its own exhibition space. It was also proposed that it should not only be artistic. Since it embraced political and ideological ideals, the museum should also seek out new cultural models to respond to the historical changes that were driving it. It should be a living museum, dynamic, in the service of the Chilean people, for cultural and educational purposes, with total participation and access to the community. As donations were for the people of Chile, a foundation should be established run by popular representation.

The Museo de la Solidaridad was projected to be the most important modern art museum in Latin America and, in keeping with the curatorial understanding of time, it was to be divided into two parts: one focusing on modern art and the other on Latin American art. This mode of acquisition would be permanent in the future as the museum expanded with new donations.

However, for this it was fundamental to legally establish the museum as an independent entity and to create its own headquarters, as Pedrosa expressed in a letter to President Allende in September 1972: “It’s already been five months since the beautiful party of the first exhibition at Quinta Normal, attended by over 100,000 people, and not a step forward has been made in the realization of the museum, but the commitments made with the artists the world over remain unfulfilled and increase (…). I feel suffocated by the commitments we have assumed, and I don’t not know how to continue taking them on indefinitely. If, until now I have worked with undaunted courage, it has been because I have trusted solely on your word.”6

In early 1973, the government committed itself to creating a legal solution for the museum, but this was not enough to either create a foundation or to establish the work as a national heritage. Lautaro Labbé, then director of MAC, said: “Things were so contingent that no one was concerned with legalizing (…). Mario Pedrosa (…) thought to establish this foundation with legal character and, then the coup came, everything ended.”7 Certainly, there was a lack of foresight, in that they thought there would be more time to create the museum.

In April 1973, the second opening of the Museo de la Solidaridad was held. Labbé explains: “When the strong fascist attack against the Unidad Popular came about, we decided it was necessary to revitalize this international aid effort and chose to re-inaugurate the Museo de la Solidaridad (…). It opened with a selection of works that had already been displayed at the first opening and others that had arrived later. The inauguration in parallel with MAC and UNCTAD, this was in early September 1973, was suspended by the coup.”8

In the period of the military coup most of the works were in storage at the Gabriela Mistral building, with the exception of those that were on display, in customs at the Pudahuel air terminal and the port of Valparaiso or in Chilean embassies abroad. After September 11, 1973 the Gabriela Mistral building (formerly UNCTAD) and the MAC were closed; both become military precincts.

After that point, all public traces of the Museo de la Solidaridad were lost. The military regime did away with the IAL documents, which contained information on the artworks that had been offered and that were to be withdrawn from customs.

The Underground Museum

The Museo de la Solidaridad was marked by the explicit relationship it had with the sociopolitical context in which it came about, and as such was seen by the military regime as a threat, a strong political opposition, holding the memory of a defeated past. But, at the same time, there was the need to safeguard this heritage, which was of great symbolic and material value, given that it included works by some of the most notable international artists, undoubtedly constituting the most important art collection in Chile.

With the military coup, the Museo de la Solidaridad came to an end and was hidden from the public for 17 years. A few days before the coup, the museum’s collection came under the auspices of the Faculty of Fine Arts of Universidad de Chile.

At the end of 1973, the staff of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (MNBA) withdrew four shipments of works destined for the Museo de la Solidaridad from customs at Pudahuel airport and entered them into their inventories. Ernesto Muñoz then responsible for public relations at MNBA described the situation: “I went to the Institute of Latin American Art and checked throughout the museum. In this catalog there was a part that said, ‘to come’ (…). I went to customs and started to ask questions, a man by the surname of Moraga answered me, we began to look for and find things. I took four customs shipments (…) got appropriate official stamps and signatures, and we withdrew them because otherwise they would have been lost.”9

Also we do not know the fate of collections that were in Chilean embassies, with the exception of the English donation, which included works by Kenneth Armitage, Eduardo Paulozzi and Henry Moore and that were returned to the artists.

The result was a fragmentation of Museo de la Solidaridad collection that even today is unknown. The different inventories that exist are contradictory, in addition there remains uncertainty about the works that disappeared or were destroyed.

Since the coup occurred, some of CISAC members tried to recover the works, and Pedrosa, in asylum in Mexico, also made steps to ensure that these were relocated to the Museo de Arte Moderno de México until the Museo de la Solidaridad could find a definitive solution: “It is crucial (…) to recover all the works donated by artists from around the world. These works (…) were in Chile in three places: in the Gabriela Mistral building (formerly UNCTAD), where about 40 works were on exhibit and another 300 were in storage. Representatives of the military junta decided to store them in the warehouse of the Museo de Bellas Arts of Parque Forestal. Another 300 works were exhibited at the Museo de Arte Contemporaneo at Quinta Normal (…), a third group was at the Maritime Customs of the Port of Valparaiso. Some individuals, close to the military junta and placed in positions of artistic leadership, are malevolently maneuvering to claim these works, not so much for reasons of cultural interest, but to neutralize the purpose of solidarity of artists from around the world with the Chilean people. We must avoid this at all costs, because I’m sure that all the artists who supported democracy in Chile would repudiate the interference of the fascist military in this matter. With this concern I write to you, to say that I will offer my help to manage the recovery of the works, in order to carry out the project of the Museo de la Solidaridad with the Chilean people, this time from outside of Chile. Given that the works entered Chilean territory as temporary importation, the donation was not appropriately documented, and the purposes for which it was collected already no longer exist.”10

The museum collection, having no legal status, was in no man’s land, and as such was vulnerable to endless irregularities, transfers of works, loss, etc. On the other hand, this created a limbo that also paralyzed any possibility of intervention and changing tutelage. It was a kind of paradoxical immunity.

Already in 1974, the cultural advisers of the military junta began to take explicit interest in the works. In a letter addressed to the director of MAC, Ossa Nena, then Secretary of Cultural Affairs of the Government General Secretariat, claims: “We were promised that soon we would receive the list of names of paintings that several countries donated to the Chilean government during the recent Allende administration. Because this is a patrimony belonging to the state of high value, we now insist that you provide us the list (…). Our Department cannot continue to ignore the requests we have made, as we have to report on these matters to the Excellency of the Junta, who are concerned about the current and future activity of Chilean museums (…).”11

Although during the military regime it was decided to hide the collection of Museo de la Solidaridad, a series of public appearances of the works were made in different exhibitions, where the provenance was not noted but rather attributed to other institutions. This is the case of the exhibition Donaciones año 1974-1975 (Donations 1974 – 1975), held in 1976 at the MNBA, with the works that had been removed by the institution from customs in 1974. In 1982 MAC of the Universidad de Chile was re-opened with an exhibition of its collection, which included works from the Museo de la Solidaridad as part of their bequest. In 1985 Exposición internacional de plástica contemporánea (International Exhibition of Contemporary Visual Art) was presented at the Instituto Cultural de Las Condes, in which the works from the collection appeared as assets of the Universidad de Chile.

Starting with this last exhibition the press began to report on the situation of the collection. They interviewed Fernando Cuadra, then Dean of the Faculty of Arts, regarding the origin of the works, to which he replied, “I discovered the existence of these works. Ninety percent are part of the Museo de Arte Contemporaneo collection and have never been displayed.” They pressed: “Acquisitions or donations?” The Dean’s response: “Acquisitions.” Further pressure: “The Joan Miró painting is also an acquisition?” Answer: “I think it is as well.”12 What seems incredible is that most of these works survived the dictatorship, both in their precarious conservation situation in MAC’s storage and in that they did not disappear.

Museum of the Resistance

The military coup did not totally break with the Museo de la Solidaridad project. The personalities that made up the Museo de la Solidaridad Organizing Committee in Chile went into exile. This same group was reformed abroad and organized themselves to continue the idea of creating the museum, but this time as a form of resistance. The museum was renamed and called the Museo Internacional de la Resistencia Salvador Allende (International Museum of the Resistance of Salvador Allende).

The idea of continuing with the museum emerged in France in late 1975, where the Secretariado Internacional do Museo (International Museum Secretariat) was formed, chaired by Mario Pedrosa with the participation of José Balmes, Pedro Miras, Miguel Rojas Mix, and Miria Contreras, its executive secretary, who worked as the coordinator while being at Casa de las Americas in Cuba. Rojas Mix notes: “We continued working for the museum in circumstances of great ambiguity of responsibilities; we did this because we had created it. Alternately Pedro Miras, José Balmes and myself were part of the Secretariado Internacional do Museo; before we were the national coordinators of the museum, then we repeated the same scheme abroad, no one assigned us, rather we were recognized by the artists from abroad and for this reason they trusted us.”13

Committees were created in different countries – Colombia, Cuba, United States, Spain, France, Italy, Mexico, Panama, Sweden, and Venezuela – set up by local intellectuals and politicians, as well as donor artists and Chilean exiles. Thus, they began to mobilize to make contact with the art world and get donations from artists in support of human rights and the repudiation of the dictatorship. The proposal was to keep alive the idea of solidarity and raise awareness about the current situation in Chile. Pedro Miras explains: “[The Secretariat’s] purpose was to do exhibitions to confirm and promote this solidarity, and with the goal that the museum would come to Chile once democracy was restored (…). This project was developed in several countries where, supported by a national committee of well known figures and thanks to the solidarity of artists, they managed to get a considerable number of works of art that were exhibited in various locations in different countries of origin, which gave rise to diverse political acts in solidarity with Chile.”14

The Return to Democracy in Chile

The committees of the Museo Internacional Salvador Allende in different countries promised donor artists to bring the collections to Chile once democracy was restored.

Under the government of President Patricio Aylwin, the newly formed Fundación Salvador Allende (Salvador Allende Foundation) started the transfer of approximately 1,300 works to Chile. So notes Carmen Waugh, first director of the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (MSSA) from 1991 to 2005: “When in 1991 works began to arrive in Santiago donated in solidarity by so many artists from so many countries around the world, the thrill of everyone involved with the MSSA was as great as receiving a loved one who was returning to Chile, because we welcomed paintings and sculptures that had accompanied and encouraged us to firmly believe that democracy would come, and that it would be possible to return to and live in our country.”15

That same year an exhibition on the museum was held at MNBA, inaugurated by President Aylwin, in which, for the first time works from all the stages of its inception were exhibited as a single collection, which undoubtedly had a national impact as a symbol of returning to democracy.

During this time period of institutional planning and reuniting collections, more than 650 works of the Solidaridad period were transferred to State patrimony. In 2005, the Fundación Salvador Allende donated to the State the Resistencia collection and the Fundación Arte y Solidaridad (FAS – Foundation of Art and Solidarity) was created. The foundation became the legal entity for the collections and assumed the responsibility for managing, disseminating, researching, and protecting the patrimony of the museum, which since 1990 continues to grow and now numbers more than 2,600 works.

It took 34 years for the Museo de la Solidaridad to fulfill its original idea and commitment. Currently, it is one of the most important modern art museums in Latin America, with one of the most representative collections of a historical epoch.

_

1 This text is an updated version of the essay written for the exhibition catalogue Compromiso y transformación: Centro Cultura de España (Commitment and Transformation: Spanish Cultural Center) Santiago, July 2011.

2 Virginia Vidal. “Museo de la Solidaridad no tiene precedents.” El Siglo, March 31, 1972, p. 10.

3 “Mañana se inaugura el Museo de la Solidaridad.” Puro Chile, May 16th 1972, p. 9.

4 The French donation included works by Carlos Cruz Diez, Roberto Matta and Victor Vasarely, among others; from Spain works by Manolo Millares, Grupo Crónica, José Guinovart, Eduardo Chillida, and Jorge Oteiza, among others; and from Mexico works by José Luis Cuevas and David Alfaro Siqueiros, among others.

5 Catálogo de la Primera Inauguración del Museo de la Solidaridad. Ed. Quimantú, April 1972, pp. 1 – 2.

6 Letter from Mario Pedrosa to Salvador Allende, September 1972, p.1. MSSA archive collection.

7 Interview with Lautaro Labbé, director Museum of Contemporary Art (1972-73), Santiago, October 13, 1990, Tape no. 11, MSSA archive collection.

8 Ibid.

9 Interview with Ernesto Muñoz, Santiago, October 22, 1990, Tape no.14, MSSA archive collection.

10 Letter from Mario Pedrosa to different members of CISAC: Dore Ashton, Ronald Penrose, Giulio Carlo Argan, Harald Szeemann and E. De Wilde, October 25, 1973. MSSA archive collection.

11 Letter from Nena Ossa to Eduardo Ossandón, Santiago, September 13, 1974. Museum of Contemporary Art archive collection.

12 Saúl Ernesto. “El Museo extraviado,” Rev. Pluma y Pincel, no. 16, July 1985, p. 20.

13 Interview with Miguel Rojas Mix, Santiago, September 13, 1990, Tape no. 6. MSSA archive collection.

14 Report by Pedro Miras on the Museo Internacional Salvador Allende, 1990. MSSA archive collection.

15 Exhibition catalogue: “Museo de la Solidaridad”, Ilustre Municipalidad de Viña del Mar, 1994.