Atelier public #2 Installation shot with Helen Quinn reading Peter Pan, The Silver River (2013), courtesy and © Katie Bruce

On Curating in Public: an Experiment

Katie Bruce with Brian Hartley and t s Beall

The exhibition Atelier Public #2 emerged from an enthusiastic response to a curatorial experiment, and from an interest in play and participation.1 The first Atelier Public was conceived in 2011 as a small space within Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA).2 In it, the public and a selected group of artists, makers and thinkers were invited to inform and shape an installation created by visitors over a 10-week period.

Those artists, makers and thinkers were invited because their practice included work on play and participation. Their contributions manifested through conversations with the curators Katie Bruce and Rachel Mimiec or through installations and provocations within the exhibition itself. The visiting public made works, observed and returned to repeat the process.

Atelier Public unexpectedly offered an opportunity for shared experiences by staff, visitors and artists alike. Because the response to the exhibition was so positive, there was an interest in continuing the process of experimentation that had begun. This second experiment in curating in public with artists was called Atelier Public #2 (hereafter AP2).3

The following is an edited conversation between Katie Bruce (KB) exhibition curator and participating artists Brian Hartley (BH)4 and t s Beall (tsB).5

The invitation

BH

I felt the invitation to play and create was specific to AP2 and “Scotch Hoppers”, since an open street space and a gallery space have individual contexts that frame any invitation presented there.6 The street is a public location where people can watch or take part without a sense of an institutional context, whereas GoMA, as a white gallery space, has a pre-existing institutional context. In discussing AP2, Katie and I were interested in the empathetic nature of the space, how an invitation can frame possibilities to create a multitude of ways for people of all ages and abilities to engage or interact.

KB

Looking back, the invitation was not the same for everyone. I had convinced myself that I was issuing the same invitation to the artists as I was offering to people entering the gallery. But I wasn’t. There was the issue of the artist fee, the conversations with the artists, and how each artist perceived the invitation and their role within the exhibition in relation to their individual practices.

It was more than an invitation to work with GoMA. I wanted to work with them. By working with artists whose practices and intentions I trusted, I could push the institution and the ideas further. Rather than a curator distilling the works into the essence of the exhibition, I wanted to be able to open up questions in public and develop concepts through the chaos.

tsB

I think Katie’s language here is very useful to unpack – curators often distill artworks, presenting them in a clear format with interpretation. In contrast, AP2 presented a relinquishing of these systems of curatorship, of traditional control mechanisms for the curator and invited artists.

Artist meeting 6th February 2014, courtesy and © Katie Bruce

KB

I am not sure I relinquished the systems of curatorship completely. I invited the majority of the artists before the exhibition in order to validate some of the curatorial decisions I was making.7 I wanted to take our roundtable conversations to a point where I could open the exhibition, with a strong conceptual grounding, to an unknown public.

My experience of AP the first time round gave me confidence that visitors would engage with the materials in all sorts of ways, often undocumented or unobserved by me. The invitation to artists preoccupied my time more, as I was placing them in an institutional discourse with access to me, which, unless they left a complaint or asked to speak to me directly, was rarely visitors’ experiences of the exhibition.

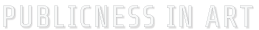

As with AP, in AP2 the recorded audience/participant voice is absent in the way that we would normally record it through comments books. There are some, but the reflections are expressed on the walls, floors and social media in an immediate and unwritten form.

ATELIER PUBLIC#2 Installation shot with visitors & comments book, courtesy and © Glasgow Museums

tsB

Acknowledging there were different levels of invitation for the different actors in the space, the invitation to artists was inherently privileging, as we were part of an existing network. We also had time to consider what we might do, and to ask questions about what was possible and/or permitted within the institution. Did the artists, makers, and curator/s push the institution further? Or did the visiting public do that without our assistance or intervention, given the system that Katie initiated? I think many of the artists – including myself – felt unsure of how to intervene without dominating the space. As a result there were many soft inquiries.

This discussion of the invitation brings up issues of specialization, which within socially engaged practice isn’t always discussed or acknowledged. There is frequently a desire for this kind of work to try and equalize, to “level the playing field”, to treat all contributions as having the same value. And while this is in many ways laudable, it is also unpractical – and naïve.

ATELIER PUBLIC#2 Installation shots courtesy and © Glasgow Museums

People came to AP2 with different expertise and/or experience, and impacted the space differently. During the exhibition there was chaos, visually. This lowered the impact of any single contribution – save that of the contribution of the overall format, the curatorial “set-up.”8 I think that one of the most interesting things for me about AP2 was what developed or emerged – a very particular kind of chaos, almost a chaotic consensus of making.

ATELIER PUBLIC#2 Installation shots courtesy and © Glasgow Museums

KB

Through those contributions and chaos I think the nature of the invitation changed. As Brian mentioned, the space was designed to be empathetic, to allow visitors to feel comfortable about contributing in an empty, almost clinical, white cube gallery space. Once the exhibition began to evolve the invitation didn’t need to be written or spoken – it was present in the aesthetic of making.

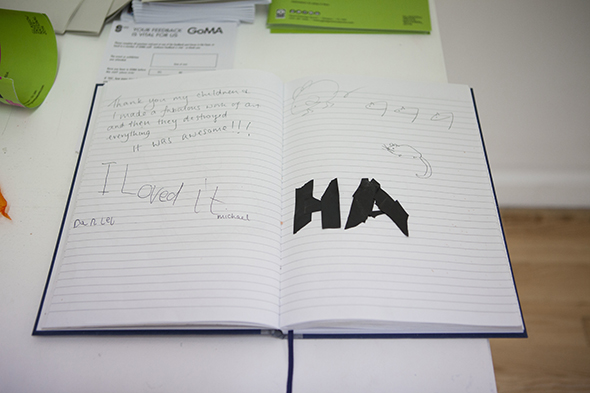

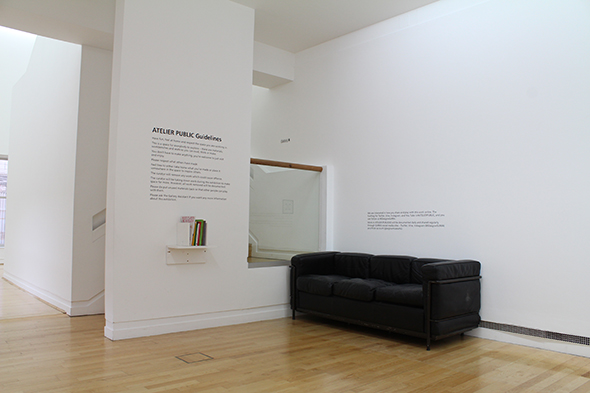

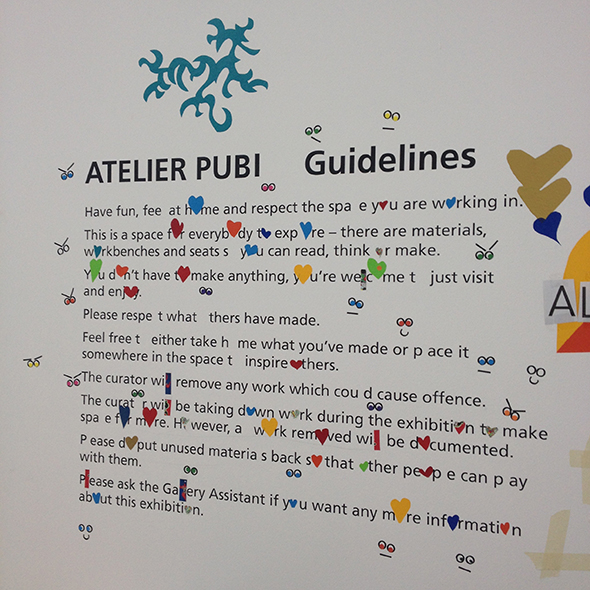

The other aspect of the invitation was the introduction of rules into the gallery. We called these “the guidelines”, and posted them at three points around the exhibition.

The rules: flexible guidelines or codified structures?

ATELIER PUBLIC#2 Installation shot with guidelines courtesy and © Glasgow Museums

KB

Having guidelines or rules became a key point of discussion. Emma Balkind suggested they were incidental and in some ways they were, as they became obliterated in the aesthetic.9 Could AP2 exist without them? Probably, but the institution could not. AP2 changed the role of visitors, from passive viewers of artworks to active agents in their creation. This in turn changed the role of the Gallery Assistants, from protectors of works to instigators of works. Because of this, staff requested some form of written guidelines in the gallery to give them confidence in answering questions.10 Along the way, “Do not write on the walls” was added to the guidelines – I think by one of the Gallery Assistants, but I am not sure.

BH

Creating guidelines framed the creative potential at the start of the process, reminding people who had attended the previous exhibition and giving clarity to new visitors. It felt important to leave space for roles to change. Once the artwork began to appear in the gallery, the work itself became part of the guidelines, giving new contexts and possibilities, adding or creating contrast, and in some cases obliterating the printed guidelines. The artwork was accumulating until the destruction event by Anthony Schrag, and then restarting and evolving again afterwards.

I wonder whether clearing the space after the destruction event had a bearing on keeping the sense of play open. Did the blank walls that appeared create a new dynamic or choice for participants?

tsB

For me there were a few key things that emerged from the guidelines – the notion of voice or attribution – whose “rules” were they? Could they be revised – and if so, how? Brian’s interest in keeping the sense of play open, evolving, is really useful here. I’m not sure how open the guidelines were intended to be once they were posted in the gallery. As a written text they did not invite editing.

But editing occurred regardless. For me, one of the most conceptually beautiful things that happened is that the guidelines were slowly absorbed into the exhibition, becoming part of a burgeoning, creative deluge. They were unraveled.

ATELIER PUBLIC#2 Installation shot with guidelines courtesy and © Glasgow Museums

I agree that the guidelines became increasingly incidental as the exhibition took shape and gathered momentum, and as words were literally absorbed into the collective creation/s. However, I do think the structure itself (in the form of guidelines) was a necessary starting point. As Katie and Brian have mentioned, there were already behavioral guidelines that underlied the larger institution, a contemporary art gallery. Posting the AP2 guidelines was a way of voicing these invisible structures, as well as clarifying to visitors what was both welcome and might be subtly expected of them.

There is an underlying assumption here that is potentially troublesome: I think we are at risk of conflating the “openness” of the invitation with freedom of creative expression. We may be guilty of characterizing openness as inherently beneficial, and restrictions as negative. All creative outputs arise or are formed by structures, limitations and/or boundaries. Without these, there is more chaos than communication. And by focusing on the openness of the invitation that was extended, we risk ignoring the substantive restrictions embedded within it.

Games and Play

KB

However hard I tried not to, there were inevitably directions in the play or creativity in the gallery. The materials were a large part of this, and in the previous edition of AP the “tyranny of the materials” was discussed as defining both the aesthetic and the play. With the introduction of new materials and work from Modern Edinburgh Film School it was hoped that the invitation to play would include changes in scale and performance.

Claire Docherty and Sonic Bothy: ATELIER PUBLIC#2 as score © and courtesy Glasgow Museums

In some ways this happened. I am however reminded of a quote from Wendy Russell at The Play Summit,11 who spoke of “control[ing a situation] by making a nonsense of it”. In many ways the play was redirected by the public, who began new rhythms of play, responding to work that was in the gallery and taking it far from the pathways that both I and the invited artists had imagined. As a curator I tried to stay back, like a playworker, waiting until I was invited into the play arena, and other times I felt like I was an alien in the play space as I knew too much to be able to genuinely play in the space. I think one of the interesting outcomes of AP2 was recognizing the dissonance between how the artists and I perceived the work conceptually, and how it was received or experienced by visitors and staff.

In initiating AP2, I wanted to explore an adventure playground model in the gallery. I was thinking about Palle Nielsen’s “Model for a Qualitative Society” at the Moderna Museet in 1968, and other permutations since.12 In talking to playworkers and researching adventure playgrounds I began to see the impossibility of this. One of the reasons was gallery cleaners, who removed work and materials daily when I was not present. This hadn’t happened during AP, in the smaller gallery. But for AP2 the cleaners tidied everything before the next day, clearing the actions of play and leaving only the products of it. Additionally, the aesthetic of the adventure playground and the shared aesthetic of AP2 was troublesome to the Gallery Assistants, and some would sanitize the space so visitors would not perceive it as messy.

It was pointed out by Gallery Assistants that the public was mostly transient, and not invested in the “playground” beyond a single visit. They left a mark and went.

BH

Acknowledging Palle Nielsen’s interest in bringing a playground inside a white cube space also highlights differences in understanding between the kinds of activities and perception in an outdoor play activity and gallery art experiences, the development of outdoor play in Scotland, a growing awareness of forest schools and outdoor learning, and reflecting the invitation and guidelines we spoke about earlier. Nielsen’s work reflects the social, artistic and political questions of its time, and these present very different contexts in Glasgow in 2014.

Infinite processes and critical review

The question I have has to do with the relationship between public participation/accessibility and what is sometimes referred to as “conceptual rigor”. The implication is that artworks and/or creative practices that involve “audiences” or are co-produced with non-specialists (in museums, or in contemporary art broadly) are inherently less conceptually rigorous than those artworks which are produced in a more traditional manner (by specialists). As practitioners working with participatory practices as a methodology, how do we negotiate these seemingly competing needs/goals? Is it true that these are oppositional? (I do not think they necessarily are, but they are often perceived to be at opposite ends of a spectrum.) Is it possible that participatory, socially engaged practices require a different set of criteria, a definition of critical rigor, even a different sense of aesthetics, than more traditional creative outputs? Are these kinds of embedded socially engaged practices in fact redefining what creative practices are/can be? The role that creative practices play with and within society?”

– t s Beall Facebook message, part of IM conversation on AP2, 13.8.15

KB

I am still working through where AP2 positions itself. I think that as part of the infinite process I have set up a work in progress for the institution. I have articulated it as an exhibition, but it could equally be described as an artwork. I could have approached an artist to bring their participatory work to the gallery like Palle Nielsen or Pawel Althamer’s The Neighbors, shown at The New Museum, New York earlier this Year, or indeed asked one of the artists involved in AP2. However, I wanted the institution to be implicit in the participation, not a temporary host.

Whether this work has truly challenged the institutional power structures remains to be seen. It certainly defied power structures, and visitors found ways to subvert the gallery experience. AP2 remained constantly in process. It was one step ahead of definition, and due to the volume of visitors, it was kept “in play” until the doors were shut.

BH

In keeping a game or activity in play, the exhibition responded to research into game play undertaken in creating “Scotch Hoppers”, finite and infinite games.13 In observing the activities at AP2, I was interested in seeing how the artwork stimulated responses and dialogue, whether an intention was to make a mark in a gallery space, create a statement.

The infinite possibilities brought artistic challenges, looking at ways to create a live movement and musical response to the artwork. In a way, the density and sheer diversity of work provided a barrier to engagement, or to bringing a sense of purpose to any response, the multiplicity of artworks presenting a feeling of impossibility, a question of artistic failure, that the spontaneous contributions somehow had more power than our subsequent interventions.

tsB

In addition to the overwhelming density of works in the space sense that Brian describes, I felt there was almost a dissonance of intention between what I am usually exploring in my work and what was happening in the gallery. I also felt that what was emerging didn’t really need my intervention – that the terms of engagement had been set and the work needed time to develop. I wondered if my artistic “input” would mostly be an insertion of my own ego or intellect into a process that had been already put in motion.14

KB

Even on the final day and public de-installation, people continued making as we, the staff, were deconstructing.

ATELIER PUBLIC#2 de-installation shots courtesy and © Glasgow Museums

The process of de-installation was not as planned, and the question posed earlier about the distance between the exhibition proposal and the practical reality is useful to consider here. In AP2 I had planned the de-installation process as a kind of ritual, where I acted as witness, acknowledging the work as it was destroyed. But for a variety of reasons, the de-installation for AP2 was brought forward two weeks. This meant that a slow process of documentation and de-installation of each work wasn’t possible.15 For me, this was an important part of the curatorial and institutional investment in the outcome of the exhibition. The distance between my understanding of AP2 as a work, the open nature of it, and the priorities of the institution it was questioning all became acutely visible during the de-installation.

ATELIER PUBLIC#2 de-installation shots courtesy and © Glasgow Museums

Following on from tsB’s question above, there may be a need for a redefined sense of aesthetics.

I am not sure if most visitors would see AP2 as a methodology, or as a form of complex questioning of ethics that surround participation in a gallery or museum. They came, they saw, they made – they ignored what they didn’t want to see and made their own contribution, often in isolation from the entire exhibition.16 For some visitors it reminded them of previous experiences, for others it was a play area for children, for still others it was a fascinating place to see politics clash with lyrics from songs, or find motivational prose and works that made you laugh. To capture all of this would have taken a large team, and turned the exhibition into something else.

tsB

Katie’s description of the de-installation process, and of visitors making “in isolation” reminds me that this method of working disallows a complete understanding of the whole. There is no possibility for curatorial distillation, or for any one person to grasp the work in its entirety.

It may be useful to consider what Paul O’Neill has called a “durational approach” to creative practice.17 O’Neill describes complex artistic projects with extended timelines, where no single participant (including the curator or lead artist) has been involved in all aspects of the artwork, where no one has a cohesive sense of the whole. The narrative or story of the artwork is therefore dispersed through multiple participants, each with specific and partial experiences.

BH

Having heard Sarah Schultz talk about Open Field at The Walker Art Center, I feel there is a methodology in the intention to create new artistic potential within a gallery context.18 Open Field is a large-scale participatory work which reframes the sense of potential and possibilities for members of the public. There is an overturning of the established “do not touch” rules of a gallery. Is this enough, or can it be rigorous enough within an artistic discourse? How does this methodology engage artistic practice around responding to an open invitation which involves members of the public, which requires a real sensitivity and respect to the work – this process in itself requires both rigor and a clarity of purpose.

tsB

Even considering these models, I think there is room to consider whether we might require a different aesthetic of participation, collaboration and co-curation. In many ways I’m looking for language that can better encapsulate these softer artistic inquiries that exist between roles and/or disciplines.

KB

For me as the curator, there are an infinite number of questions, threads to be followed, joys to be found, and difficult decisions to be made with this exhibition. I had conversations with new visitors that opened up questions around the role of the institution. I also missed thousands of conversations in the space and was told of others which were overheard, a note left in the comments book, or thoughts posted on social media. This experimental process can be defined as much by the absences as it can by what was recorded. But AP2 did provide a collective space where the nature of the invitation issued meant that people would respond, enter and encounter the work in different ways depending on their motivation for being there.

_

1 An archive of events, thoughts and reflections are on the Atelier Public #2 blog

2 For more information on GoMA

3 In initiating or representing Atelier Public for a second time in the same institution but a different gallery, there was a lot to consider. Rachel Mimiec, unable to commit time to this revisiting of Atelier Public, had given Katie Bruce permission to pursue it alone. She was interested in inviting artists that might further develop the complex conversation on democracy and participation that had begun previously. This related to some of the more complex ideas around how a public space within a public building might function ethically, and how rules and permissions define boundaries and value systems. The conversation with artists and the institution was also about exploring the distance between the exhibition concept proposal, and the emergence of these ideas in practice, and the relationship between the institution, curator, artist, and public. This is referred to in the blog post.

4 Brian Hartley is an artist who works across the disciplines of visual art, design and performance, reflecting an ongoing interest in the relationship between visual art, photography, theatre, and performance. This work takes many forms from stage design to performance and documentation, both on and off stage.

5 t s Beall is the recipient of a Collaborative Doctoral Award working with the Riverside Museum of Transport and Travel, based at University of Glasgow Theatre Studies Department. Her practice-based research investigates the use of creative events and contemporary performance practices to develop and map new strategies for visitor engagement within museums and heritage institutions. For AP2 her work involved a subtle insertion of the voices of museums staff into the gallery space.

6 “Scotch Hoppers” is a visual arts installation designed to transform the aesthetic and atmosphere of a street, inspired by street and childhood games from around the world, and playable by people of all ages and abilities. The project integrates professional dance performance responding to themes of games and play, featuring contemporary dance, parkour, gymnastics and music, and an interactive workshop program.

Scotch Hoppers was presented in Glasgow’s Merchant City, as part of the 2014 Commonwealth Games, Merchant City Festival and Surge Festival. It was initially commissioned by Unique Events in 2012 and developed with London based game developers Hide & Seek, and was presented in Edinburgh on Hogmanay 2012, and has developed through presentations at Glasgow’s Merchant City Festival and at London’s South Bank. Scotch Hoppers is conceived and directed by Brian Hartley of stillmotion working with a creative team of game developers, playground designers and theatre makers.

7 Atelier Public #2 was part of the exhibition program and the naming of associated artists presented a validation of the show. This validation through having the artists involved, enabled it to be included in the program of Glasgow International 2014.

8 By this, ts Beall is making distinction between the theoretical underpinnings of AP2 and the application of those ideas in practice. More precisely, she is interested in mapping the distance or dissonance between Katie Bruce’s vision/inspiration, her initial questions and conversations with invited artists and museum staff, and the implementation of the system that was initiated, and finally the outcomes of the overall “work”.

9 See the essay by Emma Balkind and Anthony Schrag in this publication

10 The gallery assistants were involved in writing and approving the guidelines for the first edition of Atlier Public in 2011. These were then edited for AP2 in 2014 by Katie Bruce.

11 Wendy Russell, speaker at The Play Summit, Collective Gallery, Edinburgh, 14 April 2014.

12 Lars Bang Larsen ed. Palle Nielsen: The Model: A Model for a Qualitative Society, 1968. Barcelona: Museu D’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, 2010

13 Carse, James P. Finite and Infinite Games. New York: Ballantine Books, 1987

14 For her contribution, ts Beall decided to insert, in a very subtle way, the voices and creative desires of ten Glasgow Museums staff members. She interviewed staff in different roles and asked them questions about their own creative desires for the GoMA, for Glasgow Museums, and for museums in general. These voices are usually suppressed within contemporary museum curating, and in this sense staff can be considered an under-represented public within museums.

15 This slow process of acknowledgment, documentation, and de-installation was the process used in AP1.

16 As the exhibition space was U-shaped, it was not possible to view it in its entirety, as a continuous whole.

17 Paul O’Neill and Claire Doherty eds. Locating the Producers, Durational Approaches to Public Art. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2011

18 Wide Open Public, a Velocity Talk at The Lighthouse, Glasgow, 17 April 2014.