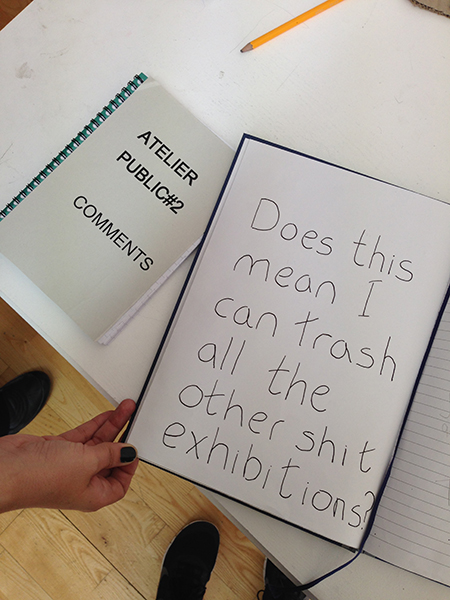

Discussion for Make Destruction event as part of Atelier Public #2. Photo: Stuart Armitt

The Negotiation is Not Over: The Institution as Artist

(The public was only an artist for three months)

A Discussion Between Emma Balkind and Anthony Schrag

Artist Anthony Schrag’s current research explores the relationship between the artist, the institution and the public within participatory settings, looking particularly at how institutions set-up/guide/support participatory projects. His contribution to Atelier Public#2—an experimental studio in an art museum context—explored how the institution framed the creative, participatory experience from its marketing and public invitation: “A space for looking, thinking, exploring and making… [Where] everyone is invited to come into, to make artworks that will become part of the installation” seemed to place an emphasis on the positively productive and “nice” aspects of expression.1

Doctoral candidate Emma Balkind’s research deals with the notion of the Commons, which has been a popular concept for curators in recent years. The Commons is understood to be the means by which we organize around a shared resource. Sometimes the resource itself is referred to as a Commons, but it is the relation by which it exists that is the important factor that defines it as commonly available. The idea of creating a Commons within a public institution is something like putting a square peg into a round hole. The sharp edges have to be rounded off for it to work, and so an acceptance from the beginning that the concepts do not easily fit together is necessary.

Much like the invited public, we were invited to participate in the exhibition in whichever way we chose. The organization of the exhibition was unlike any other show either of us had participated in up until this point. There were a very large number of people who had been consulted for their input into how the space would work, how we would invite the audience, and what events would happen. The exhibition space itself was provided to the public, empty, on opening night save for some sticky back vinyl and a few video and poster works by Modern Edinburgh Film School.2

Image 1: Vinyl Artwork (unknown author) as part of Atelier Public #2. Photo: Emma Balkind

Image 2: Young artist defending her work at Make Destruction event. Photo: Stuart Armitt

As a civic institution managed by the Local Authority and a publicly funded, policy-enacting agency, Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA) is legislated to provide inclusive and respectful art projects that do not exclude or offend any of its diverse citizens.3 Anthony was interested to test how far this “state aesthetic” could be challenged and so proposed an intervention into the Atelier Public #2 context with a work entitled Make Destruction that aimed to question the “nice” art-making gesture by inviting anyone to come to the gallery and to “destroy” artworks, rather than create them. Anthony hoped that the specific invitation to “destroy” rather than “create” could act as a provocation that might raise questions about how the institution was placing value on a certain form of expression (i.e., creation) rather than its equal and opposite force (i.e., destruction), as well as speak of the value systems at play that praised one way of expression but disavowed others and how this problematized the very notion of participatory artworks (i.e., works developed collaboratively and collectively).

We decided to have a conversation about our experience of the exhibition, emphasizing our particular interest in the ideas of ethics and commons within the show.

Like the experience of Atelier Public #2, we enter into a conversation already in progress…

The public studio: who was the artist?

A: …and even when you walk in, the making or the doing space is around the corner

I don’t think it was ever a public studio though.

E: I think it was in the first version of it, because we talked quite a bit about how differently it turned out this time. I asked her [Katie Bruce, Curator/Producer of Atelier Public #2] whether she thought it’d have been any different (aesthetically) if she had not invited any artists. She first said no, and then she said… apart from the artists’ works, which were in the space.

I said what would happen if you did a third run of the show and you didn’t invite any artists? What would be different about that, and what would that highlight in what we did? Because I feel like all that we did was talk, because we were always trying to deal with what had (just) happened. There was a timeline of events and nobody could be there for all of the events or all of the things that would happen in that timeline, so we were always trying to wrestle with what had happened. Where, if it was a studio, ideally you would go in and nothing had happened since the last time you were there.

Image 1: Page of Comments Book of Atelier Public #2. Photo: Emma Balkind

Image 2: Vinyl Artworks (unknown author) as part of Atelier Public #2. Photo: Emma Balkind

A: Is there also something about that feeling of a lack of control? Everything was constantly finished in some sense. Someone had already finished a work. Someone had already come in and done something, and you came in and you’d go: “Well alright, I could change a work, but it’s already done.”

Image of Atelier Public #2 After Make Destruction event. Photo: Stuart Armitt

E: I think the thing that I felt was that the public was obviously comfortable with moving other people’s work around and changing it, and when you had the destruction event, ripping it off the walls. But then I don’t think that anybody who was actually invited to be an artist for the project felt like that was okay for them to do that. There was never really a space to do it, because I think that the expectation for the space to be like any other space that you would normally use was always superimposed onto this situation. So because it didn’t meet with that, you felt you didn’t want to get rid of someone else’s work, because if you were in any other situation with someone else’s work you wouldn’t just take it away or move it around or something. The only other person who did something with someone else’s work was Alex, and he ended up copying works and then taking them somewhere else (out with the main space). I don’t feel that we ever challenged what was happening there.4

A: I don’t think we did. And even those people that did “destroy art”, there was never any value placed to it anyway.

E: No, because you were just acting like any other member of the public might do in that situation. I felt bad enough about it that I didn’t do anything. Obviously there was that group that came in to save stuff. But, do you think it’d have been any different if there’d been no artists?

A: I think nothing would have happened in terms of trying to challenge that space, but nothing that we did challenged that space. So in some ways, I think: no it would be exactly the same. I suppose there were all these efforts to change, efforts to think about it, efforts to negotiate it differently, but they all ultimately failed.

I wonder if the failure proves something about the power of the exhibition, or the impetus of the artists? I don’t know. If we’re still talking about it and it’s still interesting, then obviously there’s something about it that’s still resonant and still interesting to talk about. So in some ways, it was an exhibition or a proposition that was too much for the artists to deal with. Maybe not too much, but it erased the artists to such an extent. I find that quite exciting about it. I’m thinking about the idea of removing the artists.

E: I just think it’s a strange position to be in. I think there’s a lot of anxiety at least within the academy, if not within museums and exhibition making, that things should be visual—and visible—and I think that we allowed the public to be the visual and visible element in the show and disallowed ourselves to be part of that in our insistence to just continue discussion the whole time.

A: Because they were active, and we were quite passive. The public made the stuff; they were performing constantly and were actively enacting the making of it. Whereas we didn’t do anything! (laughs) But that’s interesting, because maybe that is the critique. As artists if that is our role to be critical, that’s where our “power” lay, is actually not to act.

E: I feel like our ethical imperative with this has changed from “is it right to give a public space to people and let them do what they want in it?” to “is it right that we all sat on our hands and just talked about what was happening… instead of doing something?” (laughs)

A: Yeah, you’re right it’s a total shift because in some ways we—speaking as artists “we”—we denied being part of the public. Not that we ever were, but in some ways if we’re saying, “Okay we’re going to make you, the public, active artists”, but we deny that we would be equal to them.

E: Yeah, completely deny it! But I think that the institution sets that up, and if you’re talking about a traditional notion of a Commons or a public, that split is evident within that anyway. A Commons is not really for everyone: it is given as a contained thing. To that extent, maybe it was common, and we were just outside of the scope of the benefits of it. I suppose maybe part of the question is: “Why would artists want to be like the public… in this situation?”

A: (laughs) Isn’t that… it goes back to the idea that artists are special.

E: That’s exactly why everybody didn’t want to do anything! We said, “Oh, the aesthetic is bad” or “Oh, it’s too busy and noisy”. I think we were just being precious because we’re used to a particular circumstance…

A: We’re used to being treated as special.

E: …and we couldn’t direct the circumstance, so we had to just do what we knew how to do, which was talk amongst ourselves!

A: That and deny that what the public was doing was actually valid. Which is what we do all the time anyway. It’s just that this time the public was doing art, so we said, “Well, we’re not going to do art!”

E: I think that’s what happened! I don’t know that that was necessarily a failure on our parts; it’s just a very weird situation to be put in.

Image of Atelier Public #2 After Make Destruction event. Photo: Stuart Armitt

A: What does it say about the artists? Imagine if Katie chose artists that weren’t like us, and [they] actually decided they were going to paint and be completely egalitarian and equal to people. Would it have been anything different? If the artists in good faith said, “I am equal to the public, and the public are equal to me”.

E: I think it’s possible, but I think the result would have ended up as a pastiche of what was there already. I think there was probably an anxiety of being confused with the public, and confused with that anonymity.

A: Do you think that the public was afraid of being confused as artists?

E: No! The public loved it. They thought it was brilliant because they were being given an opportunity that they would never normally get. I think the thing with artists is they want to get a good deal out of whatever they do (laughs) and so if you get put in a shitty situation…

A: It’s the same with all people, everyone wants to get a good deal.

E: But I think it wasn’t a good deal for the artists, this situation.

A: It’s interesting because the deal was given from the institution, for the art.

E: We were invited in a very different way than the public was. The public was sent a flier and we were sent emails and a promise of a fee.

A: Do you think the public knew that there were artists doing projects about the work?

E: Uh… I have no idea! The 2014 Glasgow International (GI) Festival program had the names on it, but you could take anything from that. You could think that they (the artists) did it, or you could think that they were behind the idea.5

A: I also think that most people that went into that space didn’t read the GI program.

E: No, I think an art-going audience was not who was going to go and see that. I have friends that are interested in music, and they go to the GoMA quite regularly, but they are not artists and they really liked the show and took a lot of photographs. I really feel that it was about the experience of the space, people liked that; they didn’t go for art. Maybe some of the public went to make what they felt was art, but they were on a very different plane than what the artists were on in that circumstance.

A: I think that we at this point, by writing something, we are claiming ownership of it in some way, or we’re writing our way into it. We’re making ourselves have agency.

E: I feel that I am trying to make sense of what happened, to say to myself that I have finished this and it’s done.

A: So this is your completion of the Atelier Public experience. Can I ask what the completion needs to be? Does it need to be about resolving what it does?

E: I think I just need to give something back to GoMA so that I can then stop feeling bad that I just kept turning up and saying, “I don’t really understand what’s going on here”.

A: Isn’t that enough? I mean, you were contributing.

E: It probably is, but I am not used to accepting that situation.

A: I still really think that it’s about the negotiation of the exhibition itself.

E: Do you think it was an exhibition though?

A: I do, because it did what exhibitions do. It had all the criteria of an exhibition. It was a public space in a white cube, art happened inside it, and now it’s gone. It was the proposition of an idea, quite a cohesive proposition of an idea.

E: Do you think that it is problematic for the institution to set up situations like that if artists find it impossible to produce within them in the traditional sense.

A: No, I think that’s the best thing.

E: Do you think that they should always do that?

A: Not always, but I think that if an institution has any thought of what art could be for the future, then I think that it has to occasionally challenge the artist. If that is actually erasing the artist, it is making the artist work harder because if the institution merely existed to serve the artist, then I don’t think that it would work.

E: I think that for Katie, it seemed like she felt very aggrieved that she had done that erasing, particularly with regards to Modern Edinburgh Film School. Yet at the same time I think that she really likes the project, and would happily run it again.

A: I think that’s fair though.

E: Which is interesting, that she wasn’t anticipating that tension before this started because they didn’t get the same outcome last time in the set-up that they had.

A: Yeah it’s interesting that she should feel aggrieved about the erasure of the artist, but not necessarily (although she does) about the public’s work.

E: Oh, she did. I think it’s just the public wasn’t speaking to her about it. If the public had been turning up at her office every morning and crying…

A: I think that says a little bit about the Interpretive Policy Analysis aspect of the institution. The public was only an artist for three months (or however long the exhibition was), but they stopped being an artist as soon as the exhibition came down.

E: Can we call it that: “The public was only an artist for three months?”

A: Sure! Yeah, because then they stopped and the institution said, “No, no, no, you’re not an artist any more! You can go back to being a human”. I like those problematic things, where it says something that isn’t actually that nice.

Image of Atelier Public #2 After Make Destruction event. Photo: Stuart Armitt

E: I said to Katie that I did think it was productive to do all of that talking; it was just also frivolous in not involving the public at all. I mean the only person who came along to the roundtable that was not “us” was somebody who knew Tara. So, obviously that fed back into what Katie feels about the show, but what does it do other than that?

A: For the public? Or for anyone else?

E: Yeah, just generally. It’s a very unusual situation to be in, and I also was saying to her that I felt it was funny. Last summer I was invited to do a residency on Raasay, and there were 18 of us. In that circumstance, we got there, we were not given any studio spaces or private space, we were staying in dorms. We were eating together; we were spending every minute of the day together and every day was full of activity. Then we were forced to leave it ‘til we came home to come up with something that was then given to the public through an exhibition or whichever way we wanted to mediate things.

So I was saying that I felt like these experiences were remarkably similar, that there was no space for contemplation or production outwith your own home and your normal day-to-day experience after the fact. It wasn’t engineered that way, and I was wondering whether that is a way that curators will continue to do things or whether it just happened like that.

A: There’s an assumption about how artists work: “Oh yeah, you make stuff, it just happens!” There’s not an understanding of the practicalities of how that happens.

E: Yeah, so there’s not any catering to what is needed in that circumstance. Or at least the artist is going to have to work that out for themselves, which is an echo of the way everyone needs to be freelance and work on all aspects of what they do by themselves now. If an institution commissions a circumstance like that…

A: So then it becomes about institutionalizing an artist, if you were to say, “This is what an artist does, we will give you that, that’s what an artist needs”. Then, it’s like: here’s this amazing studio; here’s your facilities, “but I don’t make art so this studio is useless to me!”

E: That was one thing: Katie was there virtually the whole time, for everything!

A: Yeah, but she is the main artist. That’s something that would be interesting to talk about, the institution as artist. We were secondary artists to her in some ways.

E: Yeah, I can see that. So, do you think that what she did was not curation in this circumstance, then?

A: I dunno, because maybe she’s not the artist, maybe she is the curator… No, I would say she is the artist because, you know, the whole idea of the artist and art being a question, of proposing difficult questions.

In The Aesthetic Unconsciousness, Jacques Rancière describes Oedipus and Hamlet as the classic “fools” who both “know and do not know” who “act and do not act”. He goes on to suggest that the aesthetic realm therefore is a “thought that does not know”, where there is a “logos in pathos and a pathos in logos”6. In this sense, Atelier Public #2 formed an ideal Aesthetic Realm, as it did not complete itself but rather stayed unfixed in its pluralities… In some ways, that is what Katie was doing with the exhibition, problematizing what “public art” was and was not.

E: Yeah, though she never outwardly did it.

A: No. And, if that’s the case, if she was the artist and not the curator, does that position it more problematically, because we just became materials to her artwork?

E: Ohh! You were going to be equated to the sticky back plastic?

A: If that was Katie’s work or the institution’s artwork, the artists became just another mechanism to produce for them. We had no agency in and of ourselves. If that’s the case, then maybe that’s why it was so problematic.

E: I think I would look at it in a less pointed way than that. There are parts of that, that I definitely would agree with, but I think it was just genuinely a development from a previous project and there wasn’t a lot of consideration as to how differently it might turn out, being in a new space and not involving the artist Rachel Mimiec, who was assisting Katie with the first one. Maybe you are right, maybe in the absence of Rachel, Katie did become the artist.

A: Maybe it’s the institution as an artist rather than Katie herself, because it was the institution that was making the gesture, the provocation, the spaces. They instituted themselves through Katie; she was the one pushing it through.

E: Okay, I would be more inclined to agree with that.

A: That is an interesting thing to think about, how can the institution be an artist? I don’t want to think about that, that’s too complicated!

E: Well, it was very institutional the way that things became. The way that work was farmed off to other people repeatedly. So that would be quite a convincing thing to say.

A: Maybe I will start with that. I will probably still want to think about the institutional approaches.

_

1 The first Atelier Public was conceived in 2011 as a small space within Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA). In it, the public and a selected group of artists, makers and thinkers were invited to inform and shape an installation created by visitors over a 10-week period. Because the response to the exhibition was so positive, there was an interest in continuing the process of experimentation that had begun. This second experiment in curating in public with artists was called Atelier Public #2

2 Modern Edinburgh Film School – the title of artist Alex Hetherington’s ongoing project was one of the first featured works of Atelier Public # 2. See Alex’s essay in this publication and for more information

3 For more information on GoMA

4 Counterscript Alexander Stevenson 31 April – 27 May 2014

5 Atelier Public #2 was part of the Across the City program of Glasgow International – a biennial festival of contemporary art.

6 Jacques Rancière. The Aesthetic Unconscious. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2010, p. 6