Lívia Flores. CARRO-CORAÇÃO: Bloco Império Colonial, 2017. Still

CARRO-CORAÇÃO (HEART-CAR) a videoexperience

Livia Flores

1. CARRO-CORAÇÃO is a videoexperience with Clovis, João Wladimir, the members of the Bloco Império Colonial [Colonial Empire Bloco], and myself [T.N. “blocos” are neighborhood Carnival festive musical groups]. The images were recorded in February 2017 at the Colônia Juliano Moreira* in the days running up to the opening of the exhibition Lugares do delírio [Places of Delirium] held at the Museum of Art of Rio de Janeiro (MAR) that coincided with pre-Carnival events that year. A year later, at Carnival time again, I write this text. Completed in October 2017, the video work presented here for the first time includes the projeto carro alegórico [allegorical car project – understood as both a car and a reference to allegorical floats (carros in Portugues) of Carnival parades] as a kind of dislocated excerpt and, at the same time, as a pulsating-percussion. The idea is that it reverberates.

*[T.N Colônia Juliano Moreira – Juliano Moreira Colony known as “Colônia” is a mental health complex dating from the early 20th century in Jacarepaguá, a northwestern suburb of Rio de Janeiro. It is the asylum where the artist, Arthur Bispo do Rosário, was interned and his namesake museum, Museu Bispo do Rosário Arte Contemporânea is now located.]

A VIDEOEXPERIENCE, is not intentionally experimental, neither in its conception or fundaments of making, but rather because it is impregnated and constituted by the word experience itself, being of special interest to the work as a whole. EX PERI ENTIA meets the outside (EX) and the boundary (PERI) in the act of learning-knowledge (ENTIA). I understand it as the moving and orbiting desire of the outside, of what escapes, of what was, EX operating in two vectors, the spatial and the temporal. It interests me to think of the implicit topology of the word being crisscrossed by forces and tensions, conferring on the periphery a necessarily reverse centrality, which inhabits the margins, pulls towards the edges, makes one travel across vast confines.1

“The images appear every now and again in the city, on the fringe.”2 CARRO-CORAÇÃO is a slow motion videoexperience with a lot of delay. It requires re-seeing.

2. The eye lands on Clovis’s pieces without being trapped by them. They are there as if they had not been informed that they should adhere to the camera frame, as if the camera failed to lure them into the picture.

“Is it for time this here?” Asks Clovis with the camera in his hand.

To the praise “this camera here is good,” Clovis continues his movement. “Just one more there, the last one.” The eye turns (the body turns), seeks, points, escapes being seen. The landscape becomes chronicle: it comes loaded with the pieces (cars), with everything that was there and passing by at that moment. A small square frame inside a small square courtyard. By reaching the boundaries of the frame that transports it to the field of the image, the landscape passes with everything that goes on in it, bringing with it the sounds of its own making. Landscape presupposes windows. The framing operates the image’s chronic field – of Cronos, the lord of the cut. Of time. Of the chronological and of the stopwatch. Of the film and the filmless, of the video.

Videoexperience permeates filmless cinema, sinks into its bloodless heart that at this very moment expires, wheezing cold air. This, in turn, merges with videoexperience producing mist. One or the other (Videoexperience (VE) and filmless cinema (CsF)) thus remain, by reciprocal friction, at a constant boiling and evaporation point.

3. Filmless cinema can be an effect of listening to the noise around us, to music, to voices; or an effect of reading produced by written words or images. Captions and titles can be abbreviated forms of filmless cinema.3

In this way, perhaps, it is as an effect of film or of video that enables filmless cinema to become an experience.

Attention: You may be reading filmless cinema in these paragraphs.

A film is like a poem.

KINETIC POEM

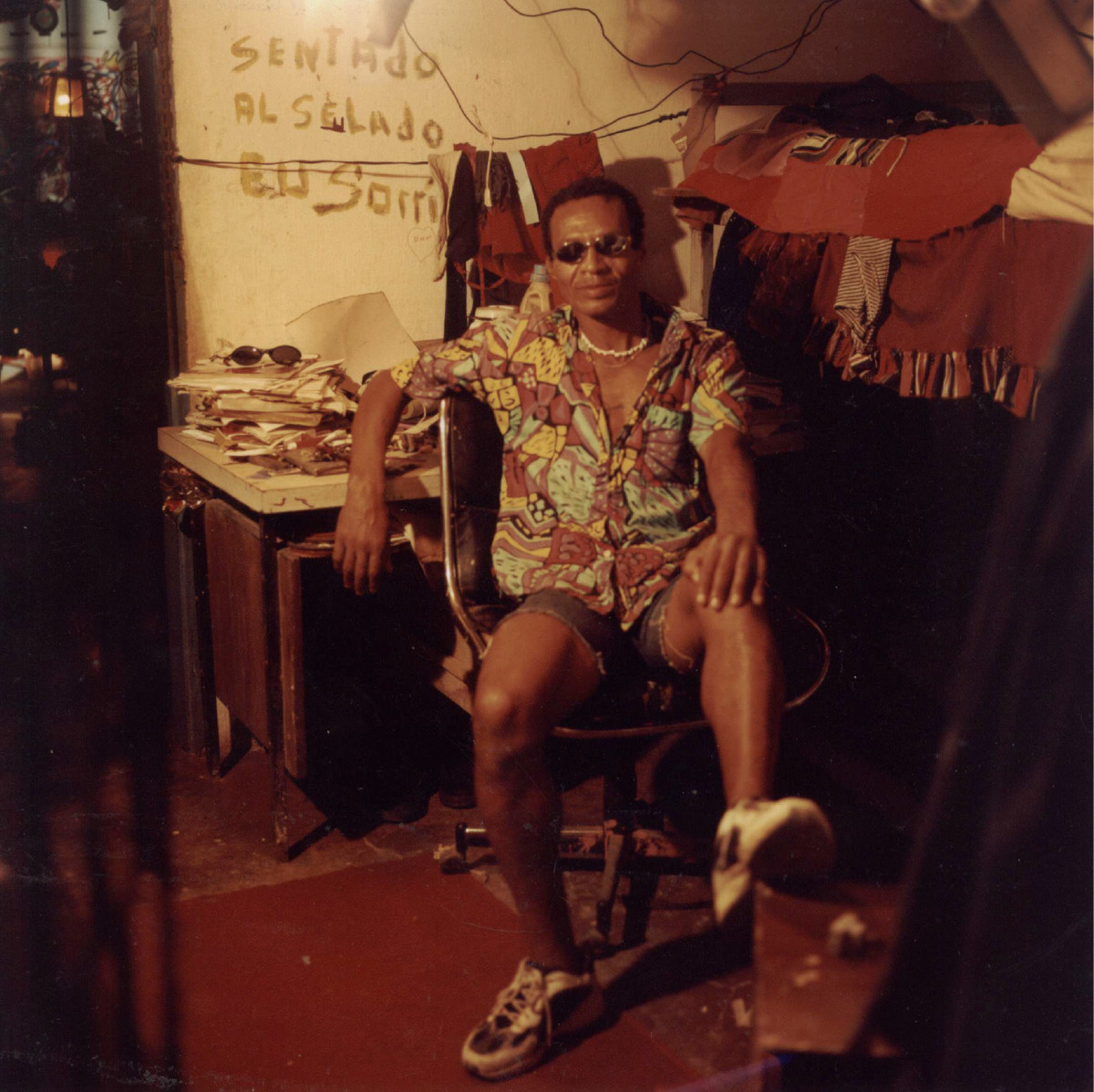

The poem varied according to the amount of clothes hanging on the clothesline in front of it. Depending on the day, I read: SENTADO: AL SELADO* I (who am I?), ALONE (at your side), SMILE, in doubt about the present or past tense. I AM SMILING, SMILED? The intense nostalgia of sitting next to you. Although this at-your-side was problematic. At your side implied the saddle, the figure of the horse, and in it taking turns with the positions of mounting and being mounted. An enigma proposes itself in this concomitance of positions. It was: I SMILED.

*[T.N. SENTADO (Seated): AL SELADO (Al Saddle) – “al selado” in Portuguese rhymes with “ao seu lado” meaning at your side.]

Fig 1. Clóvis at the Fazenda Modelo [Model Farm] 2004. Photo: Wilton Montenegro

4. Like a “wagon drawn by five donkeys, carrying coffee”, Clovis’s cars, also in songs, come loaded with landscape. Or rather, they do not disconnect, but pull it with them.

But WHAT LANDSCAPE?

Cars make us give in to a superior condition. They divert us from the grasses and the “stone in the middle of the road”4 in favor of a broad horizon that our Renaissance mind-set organizes as landscape. We travel around in movable capsules as if we were comfortably installed in a camera obscura of transparent tin, like detached bodies in suspension and speed. The contemporary hyperkinetics described by Sloterdijk is only disrupted when cars are immobilized in traffic jams or any other type of obstacle to their redemptive automobility.5 Then we return to the ex peri entia: “everywhere where the unleashed automovements cause bottlenecks or turbulence, rudiments of experience are born: in them the active modern transforms into a postmodern passive,” says Sloterdijk.6

The automobile, and I would add cinema, first cousins as seen by the Fordist logic that produced both, contributed to the full realization of this unique utopia of modernity that has in fact gained consistency. Precisely through their close co-laboring, kinetic forms of imaginary and corporal sensation seek to reproduce themselves on concrete spatial coordinates. Their correlate is the city, understood as a place of projection and reflection of images. In the neoliberal version, the dispute between the imaginary and the territorial will intensify. But it’s enough to think of Brasilia to understand its genealogy. “From this arises the fundamental link between movement and architecture as the two fundamental factors in the construction and self-representation of the polis as a political-kinetic fantasy of contemporaneity.”7 This fantasy, observes André Lepecki, corresponds to the idea of man destined for free transit, the lord of his/her will, free to move according to their destinies. It is then up to the city to play the role of emblematic image, appearing as a spectacular stage for such fiction.

Clóvis’s cars are vectors, shot through with a kinetic power that manifests itself in the multiple representations of its motor-sensitive scheme. However, they tend to get stuck. They are prototypes of a new manufacturing to be assumed by contractor-assemblers. They weigh. Mortar, cement, stones, brick. They need to be loaded – or removed. They claim ground.

They are stones in the middle of the road.

Fig 2. Car under constrution or in process. Clóvis, Fazenda Modelo, 2004. Photo: Wilton Montenegro.

Fig 3. Car under constrution or in process. Clóvis, Fazenda Modelo, 2004. Photo: Lívia Flores.

5. Auto-immobile.

Contains in itself the allegorical terms that nourishes the projeto carro alegórico.8

In the middle of 2016, fourteen years after the first visit to Fazenda Modelo [Model Farm], where I met Clovis, I revisited it in the hope of finding still intact what I had long understood as a counter-monument. An opportunity had presented itself to try to rescue the object and the project.9 At issue, were possible answers to curator Tania Rivera’s invitation to “retake the gesture” that was realized in Puzzle-pólis II (2004). In that year 58 pieces of Clovis’s – many buildings and some cars – left the art and craft barn of the Fazenda Modelo for the 26th São Paulo Biennial in order to create a kind of city hallucination.10 At least that was my intention.

The cement car was built on the eve of the definitive closure of the institution that for almost two decades had been a homeless shelter for those on the streets of Rio de Janeiro (1984-2002)11 – the largest in Latin America. The pieces left, Clovis was provisionally housed in a downtown hotel, but the car stayed. Its dimensions extrapolated any door wedge or window through which it might pass. In order for it to exit would require the partial destruction of that municipal patrimony building. Maybe the projeto carro alegórico should be called Puzzle-pólis III.

We follow the footsteps of Clovis in Rio’s sub-urbia between the Fazendo Modelo and Colônia Juliano Moreira.12 Two rural areas that hold in common a history reconfigured by hygienist policies. The territories of the former 18th century Fazenda Engenho Novo [New Mill Farm], originally the Engenho Nossa Senhora dos Remédios [The Mill of Our Lady of Remedies], were transformed into the Colônia dos Psicopatas-Homens [Colony of Male Psychopaths] between 1912 and 1918, eventually becoming Colônia Juliano Moreira in 1935. Today, the Colônia designates the neighborhood that houses the ruins of its history, a hospital complex with several pavilions, the Museu Bispo Rosário Arte Contemporânea (mBrac) [Bispo Rosário Museum of Contemporary Art], FIOCROZ facilities (Fundação / Foundation Oswaldo Cruz – a national institution of science, health and technology affiliated with the Brazilian Ministry of Health13], some commerce and new apartment blocks of Minha Casa, Minha Vida [My House, My Life – a government home buying assistance program]. Some of the residents dislocated from the Rio suburb Vila Autódromo also live there now.14 In 2016 the territory of the Colônia was split, now crossed by the Trans-Olympic Highway.15 A new historical layer cuts off old paths.

The surroundings delineate the context. The city is transformed by the imperatives of the alliance between public power and capital interests of contractors and image dealers. A global kinesthetic aesthetic is imposed on the inhabitants of the marshy labyrinths of the Jacarepaguá region. The concrete car in the shape of a large Volkswagen Bug, of dimensions similar to those of a pickup truck, expands its phantasmagoric potency. While it stayed on the abandoned Fazenda Modelo for many years, it was no longer there. I proposed to Clovis to build it again.

Tania Rivera’s invitation came as part of her curatorship for the exhibition Lugares do delírio together with a artist residency proposal at the Polo Experimental (a project of mBrac) known as “Polo” – a cultural community center for mental health users and families administered by the museum including the Atelier Gaia an art studio/collective.16 The residency program was agreed upon by mBrac and MAR for the purposes of the exhibition. The proposal commissioned new works to be created in an open format, elaborated by the invited artists (Solon Ribeiro, Gustavo Speridião and myself) drawing on our coexistence and collaboration with the artists of the Ateliê Gaia (themselves former asylum interns): Patrícia Ruth, Clóvis dos Santos, Arlindo de Oliveira, Leonardo Lobão, Luiz Carlos Marques, Pedro Mota, Alex, and others, who participated more episodically during the period of residence. We became repercussive channels of that productive context.17

I walked through the Colônia in order to map possible locations for the car. I sought among the many lands tilled along the road a place of visibility for drivers and passers-by. Clovis responded by proposing more sociable uses: a car-bar around which people could meet to talk and make music, his greatest interest. The car began to move.

Its principle construction, based on an automobile chassis, was the same as an allegorical Carnival car. The mobility varied in relation to the weight of the car, from land settling difficulties, to the possibility of making the wheels spin, or not. It could circulate towed, pulled or pushed. With the approach of Carnival dates and the opening of the exhibition, the name of the project and the intended object became confused. In this disjunctive tautology, what escaped was the allegorical character of the car-house. It gained more festive airs as a more feasible strategy, migrating from a mound-like state to a skeletal one.

We lacked carnival technology, Clovis and I, although the tambourine and a song always resounded. But his songs are not of Carnival; they are nomadic songs, modulating themselves to the local cadences of many outsides,18 memories of the singer: Master Verdelinho.19 I track listening traces. The more I hear, the more I (re)cognize clues from a vast musical geography rooted in time. Appearances of a repertoire. Songs, critters, plants, things, corners, I see/feel affections of Brazil and situations-cinema. As in the paintings of Antonio Bragança.

Wednesday was the day of meetings at Ateliê Gaia. I looked at artworks, talked, listened to stories, accompanied discussions and projects. People, movements, events, spaces, and relationships were reverberating. When I returned to the city, it was Colônia that had expanded its territories.

Fig 4. Lívia Flores. CARRO-CORAÇÃO: Colônia Juliano Moreira, 2017. Still.

In the Ateliê, the question revolved around the chassis: whether of car or canvas. I think of the artistic circuits in which I participate – or not, including that one. I observe transmission and control systems, accesses, invisibilities, discourses, my own. Gaia is a sounding board, amplifying questions about art and the city. I asked them about the Colônia – what it was like, what they remember, what the word “colônia” [colony] meant to them. The answer came in the form of Carnival music for the Bloco Império Colonial. “Art is in the musical / it’s in the mosaics and paintings / Let’s fight for an ideal / decolonize this carnival.”20 The allegorical car as pulled by the boat/float – CAR NAVALIS.

Fig 5. Lobão. Standard. Bloco Império Colonial, 2017. Photo: João Waldimir Bernardes

Fig 6. Arlindo. Mask. Bloco Império Colonial, 2017. Photo: João Waldimir Bernardes

Fig 7. Luiz Carlos. Costumes. Bloco Império Colonial, 2017. Photo: João Waldimir Bernardes

Fig 8. Preparations for the presentation at MAR. Bloco Império Colonial, 2017. Photo: João Waldimir Bernardes

Visits intensified until they became daily in the two or three weeks preceding the only public presentation of the allegorical car, in the process other actions and agents were added.21 With the arrival of the chassis, we began to work in the blue shed, next to the maintenance workshops of the Colônia, the locale of some deactivated former senzalas (slave houses) originally part of Mill operation and the plantation/homestead. Every May 13 the space hosts a feijoada [T.N. Brazilian national stew with beans/meat of Afro-Brazilian origin] in memory of the slaves and the Law [Lei áurea in 1888] that promised to free them. Under the eye of “preto velho” [T.N. literally “old Black man” – an entity of Afro-brazilian religions evoking ancestral traditions and life at the time of slavery] the oven, sink, tables, and benches await that day. In the silence, everything buzzes. By closing the doors at the end of work, a hail of chestnuts on the zinc roof seems to be the sound carrier of the energies that accompanied us.

Clóvis views it as a service to be rendered (as well as the other artists, and myself). He asked me one day, annoyed:

-“You do not have to make this car, just go to Volkswagen and buy it.”

-“Yours is art.”

-“If you want a car, why don’t you go to a store and buy it, it’s art.”

-“They are all the same.” I replied: “Yours is different, unique.” No resonance.

Figs 9-10. Lívia Flores. CARRO-CORAÇÃO: Clovis with the carro-coracão and a car made with paper maché, 2017. Still

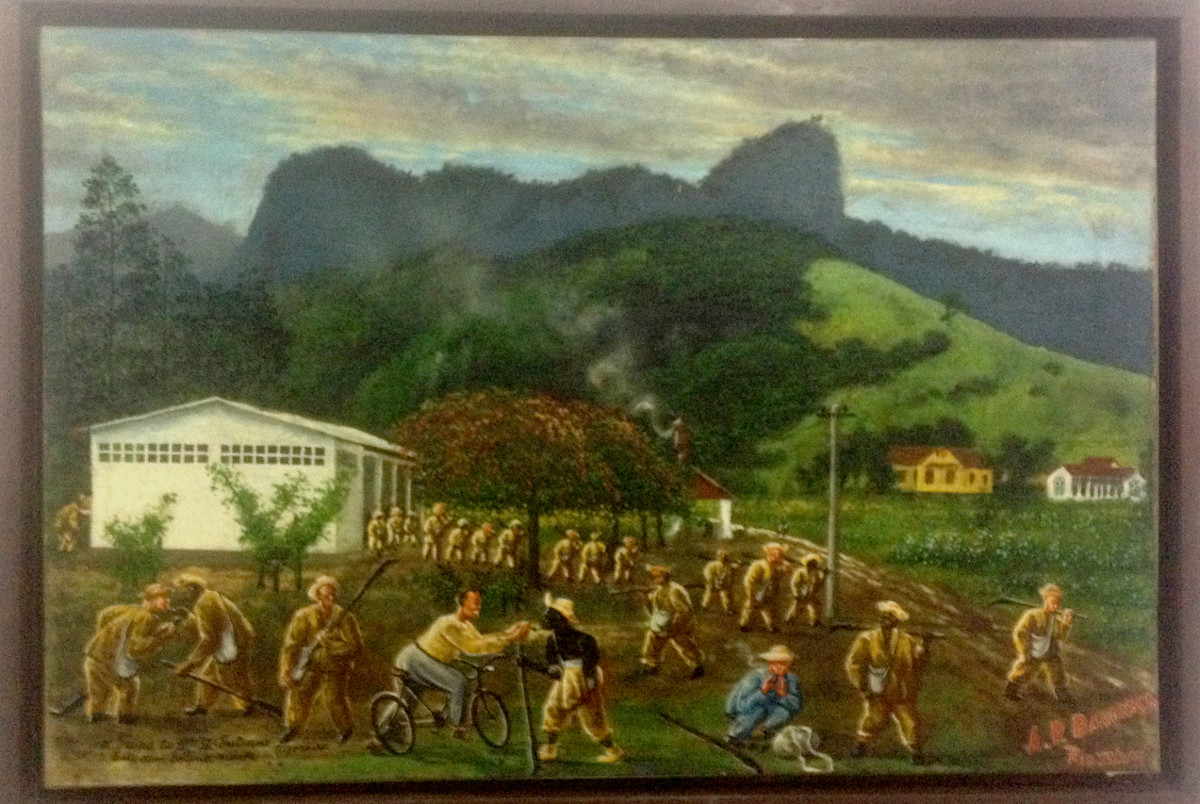

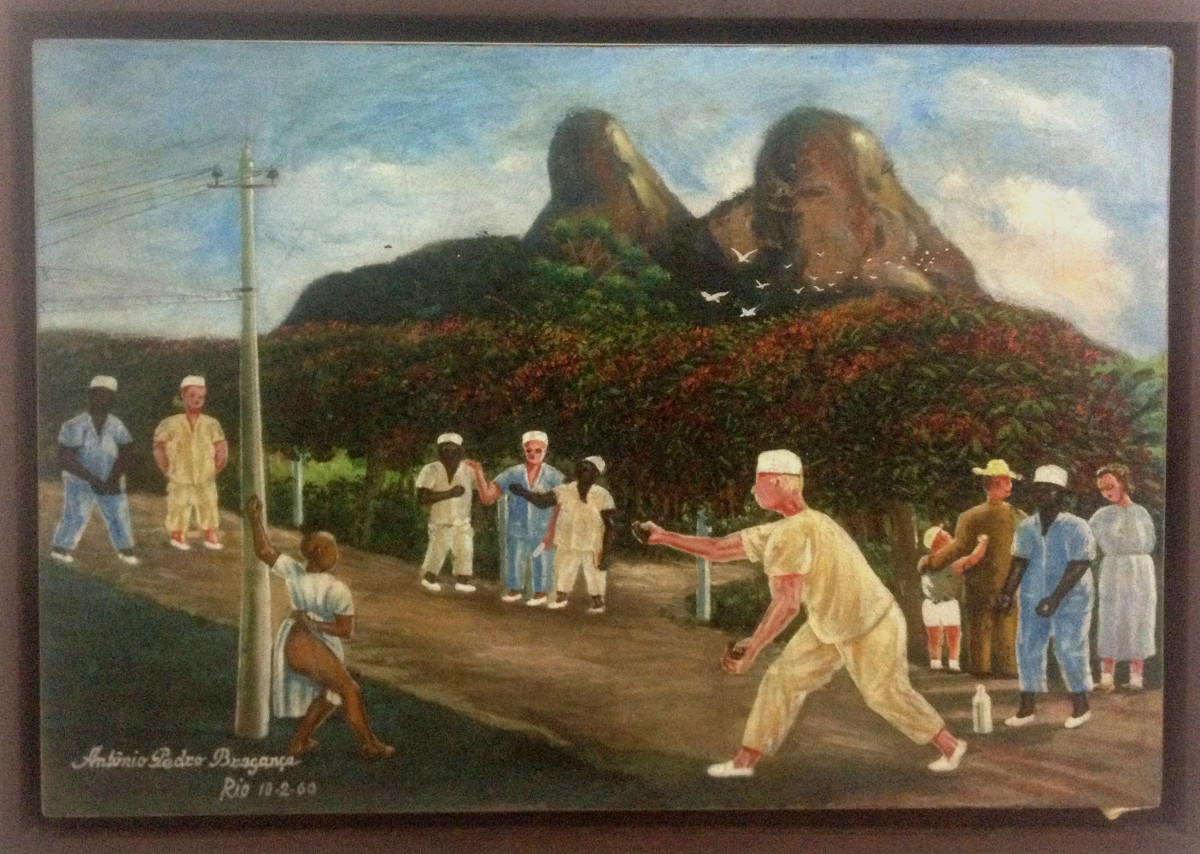

7. Months after the completion of the project, I visit the mBrac. In the entrance hall, the car and banners that accompanied the presentation of the car/float are being exhibited. On the second floor, there are works by the Gaia artists and a gallery with the paintings of Antonio Bragança, recovered from the archives of the Colônia.

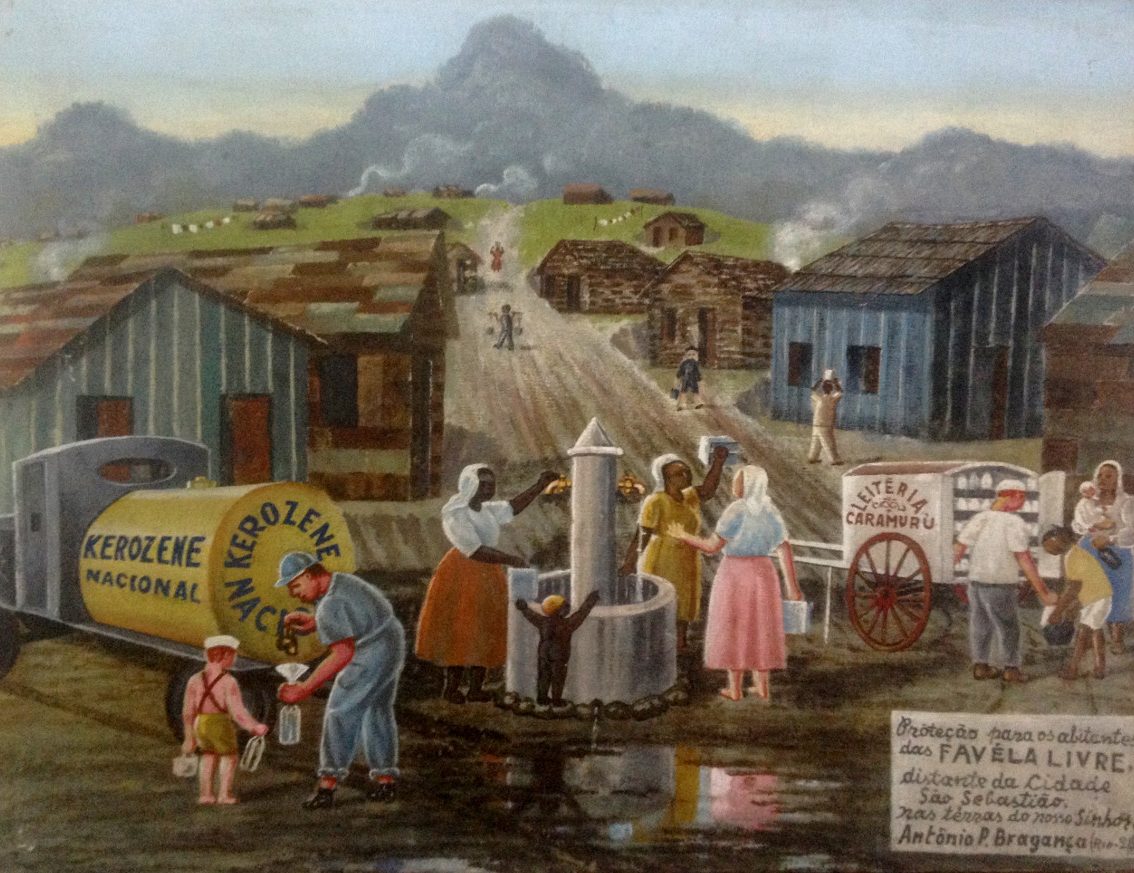

I recognize in his paintings the landscape of the Colônia marked by the stone wings that hang over it and also a certain map of the city in which imagination and reality interpellate each other. There is the dream of the free favela, protected and with supplies; milk, kerosene and water spouting in the foreground, smoke in the shacks signaling food preparation, clothes on the clothesline, children, men and women freely circulating, entertained with their chores, their lives (Proteção para habitantes das favelas livres [Protection for inhabitants of the free favelas] undated).

Fig 11. Antonio Bragança. Proteção para habitantes das favelas livres, undated.

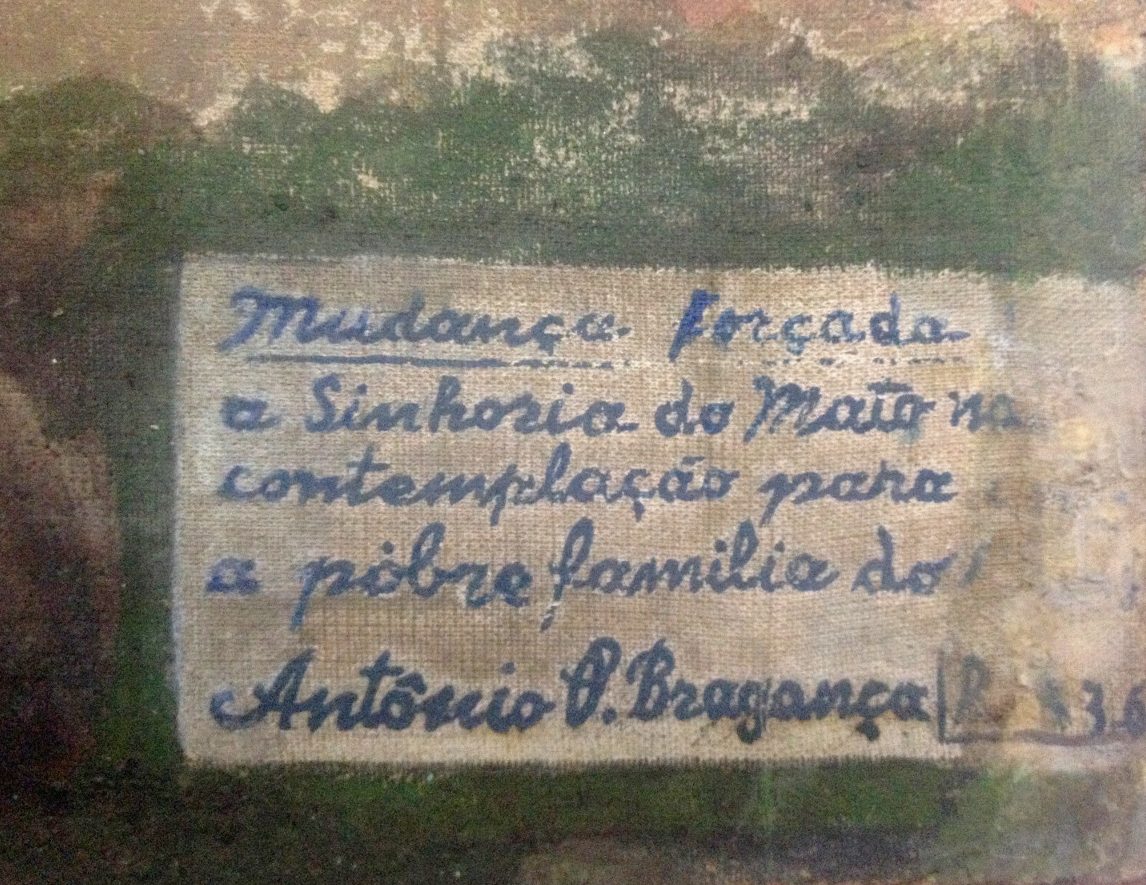

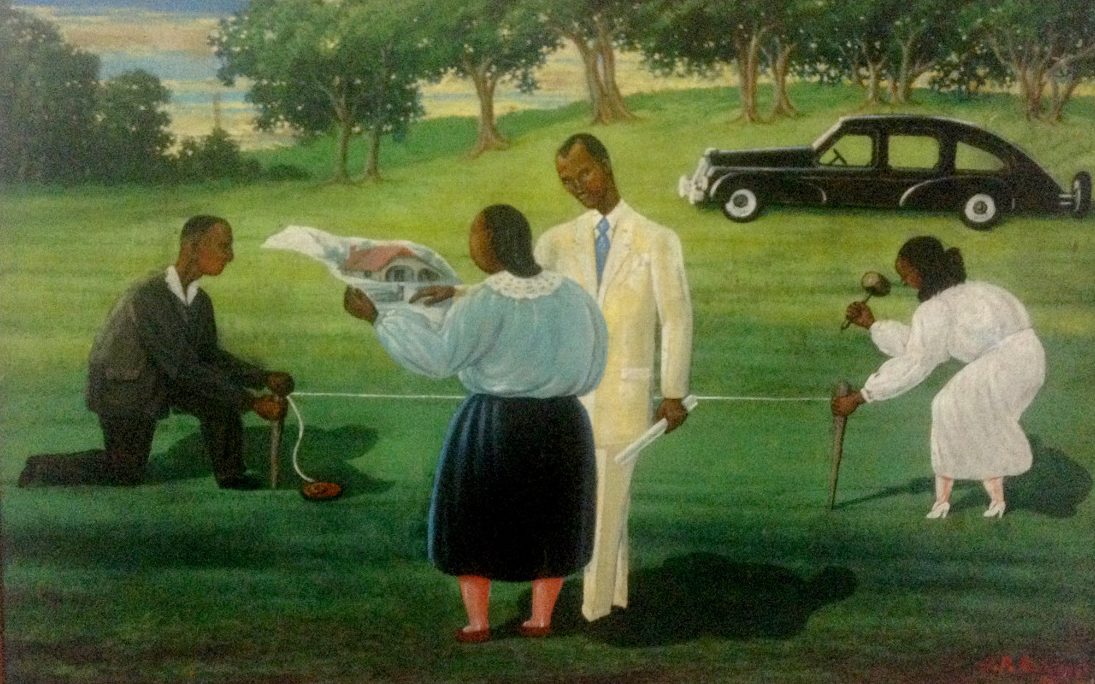

There they are linked as if by a common nexus, the scene of the withdrawal of the “poor family” being contemplated by the “Landlord of the Bush” (Mudança forçada [Forced Change] 1936) and the elegant citizens who conquer land, house and car in a black society (Sem título [Untitled] 1968).

Fig 12-14. Antonio Bragança. Mudança forçada, 1936.

There are pavilions; still with the same colors in A tropa do Sr. Dr. Luciano Moreira está com botina nova [The Troops of Mr. Dr. Luciano Moreira Have New Boots] 1961. Could they be the troops of Dr. Juliano Moreira – the psychiatrist that give the Colônia its name? Are the male psychopaths the ones that are marching like soldiers and turning into peasants armed with sickles? Could the artist and former Colônia intern Arthur Bispo do Rosário be among them? Could Brazilian pianist and composer Ernesto Nazareth, also an asylum intern, have passed similar ranks? The detail of the new boots could only be ironic if they had not been the distinctive footwear in the times of slavery. In the painting Sem título [Untitled] undated, who is having a fit? A black man or woman. Color matters. Is it really a fit? The proximity of the figure to the post suggests the memory of the pillory. Who helps, really helps?

Fig 15-16. Antônio Bragança. Sem título [Untitled] undated.

It might be that the polis contained inside a coconut from Bahia is sweet. As Clovis’s song muses. We do not know. Its thick bark protects it from the light of day and from our gaze. “The sun does not rise but the moon and the stars do every day,” sings Clovis, poet-singer. “That she laughs, father, that she laughs, father, I want to smile, father” – that she laughs.

8. The question of names. Proper, anonymous, and appropriate, perhaps improper. CARRO- CORAÇÃO is an allegorical name. It insists on the metaphor of heartbeats: “he who threw at us has erred.” Always.

Lívia Flores. CARRO-CORAÇÃO: Bloco Império Colonial, 2017.

***

Lívia Flores

Lívia is an artist and researcher. She holds a PhD in visual arts from EBA /UFRJ. She is an adjunct professor in the School of Communications and the Postgraduate Program in Visual Arts at the School of Fine Arts at UFRJ. She has held various solo exhibitions including at the Progetti Gallery (Rio de Janeiro), MAMAM (Recife) and the Santa Mònica Art Center (Barcelona) and has participated in collective exhibitions in Brazil and abroad, such as Lugares do Delírio (where she was one of the artists in residence at the Museu Bispo Rosário de Arte Contemporânea); Passagens: Serralves Collection, Prêmio Situações Brasília and 26th São Paulo Biennial. The book Livia Flores (ArtBra collection, Rio de Janerio: Automatica, 2013) is an important reference on her work.

_____

1 These were regions dominated by the ancient goddess Artemis. Reading Jean-Pierre Vernant allows us to locate the question of the peripheral in relation to the city, to the polis, the center point of work. I adopt the author’s caveat that it is not a matter of taking the Greeks as a model but of trying to understand, from the distances that separate us, how a society approaches the question of otherness. The “sovereign of the margins,” he says, is present where the boundaries between water and land, cultivated and agricultural space are imprecise: “borders where the Other manifests him/herself in the contact that regularly stays with him/her, in truth living the wild and the cultivated in opposition, but also in interpenetration.” The hunting and war divinity is mobilized whenever savagery threatens to bestialize men, whether in dealing with their fellows or with animals. Protector of childbirth and babies, she watches over all life, no matter how fragile or strange, and accompanies adolescents in their transition to culture. She prepares passages and at the same time preserves frontiers, “reserving a place for what is not itself, for the xenos” – being that she herself was a goddess considered foreign by the Greeks. By adopting as its own this “barbarous, savage and bloodthirsty” deity (as one of the original versions of Scythian origins cites, a people that does not know the laws of hospitality), the Greek city “constitutes, from the other, with the Other, its own Self.” The question refers to the philosophical problem of identity, which cannot be conceived and defined except in relation to difference, “to the multiplicity of others.” An invitation, therefore, says the author, “to give due importance, in the idea of civilization, to a spiritual attitude that has not only moral or political value, but a properly intellectual one, and which is called tolerance.” I tend to believe in an attitude that goes beyond tolerance, towards attention, exchange of glances, listening. Jean-Pierre Vernant, Com a morte nos olhos. Figurações do Outro na Grécia antiga: Ártemis, Gorgó (Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1988) 15-37. Original title: La mort dans les yeux: figures de l’Autre en Grèce ancienne by Hachette (first published 1985)

2 Livia Flores, Como fazer cinema sem filme? [How to Make Filmless Cinema?] Doctoral dissertation (Rio de Janeiro: PPGAV-EBA-UFRJ, 2007) 155.

3 The Theogony of Hesiod is for me one of the earliest records of filmless cinema* that is shared through listening / reading. The poem opens with an invocation to the Muses. With their singing power, they maintain (sustain) the cosmos-world that will come into existence/be narrated through their songs: its geographical accidents, mountains, islands, rivers, gods, primordial forces. They are the nine daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (memory), who burst forth in the thick of darkness, shrouded in mists, singing and dancing, unveiling it at their pleasure. Manifesting themselves through the singing of the poet to whom they grant their language powers, their voices, and dancing bodies have the prerogative to bring multiple manifestations of beings into presence. The condition of luminosity, therefore, does not guarantee, by itself, any sustenance to being. To show, you have to listen first. By silencing, they let all things and beings fall into oblivion, this vast domain of non-being shared with the night and with the abyss (the bottomless Tartar). “We know how to speak many false things as though they were true; but we know, when we will, to utter true things”(as translated by Hugh Evelyn-White). Hesiod, Teogonia: a origem dos deuses. Translation Jaa Torrano (São Paulo: Iluminuras, 2007) 103.

* In addition to a certain dramaturgy of darkness and light (including mist as a zone of liminality), for which film and light projection serve as a model, it is of interest here the regime of intermittency that is established between manifestation and language, completely eliminating any stability of being. In the field of art, such stability (of the “art” object) is denied when Duchamp speaks of “apparition of appearance:” the configuration given by a person who hears, sees, reads (apparition) to a skeletal information (appearance) of which the guarantee of a link with a supposedly true or original form is non-existent or impossible to establish. “The spectator makes the picture,” says Duchamp (it may also be a ready-made object produced in series): something called “art” in an “art” environment is enough to produce the art effect, a sensation of art? With this, in my view, Duchamp demonstrates the working conditions of filmless cinema: 1. it mobilizes spaces; 2. it works with the continuum, but does not dispense with the cut, on the contrary, the cut is its working condition – or as the poet Wally Solomon says, “Memory is a film editing station;” 3. it can be shared; 4. it is inseparable from a discursive condition.

4 “In the middle of the road there was a stone / there was a stone in the middle of the road / there was a stone / in the middle of the road there was a stone.// I will never forget this event / in the life of my so fatigued retinas. // I’ll never forget that in the middle of the road there was a stone. // There was a stone in the middle of the road / in the middle of the road there was a stone.” Poem by Carlos Drummond de Andrade “No meio do caminho” [In the Middle of the Road] published in 1928.

5 “Because in modernity the Self (Soi) can not be thought without its movement, the I and its automobile constitute a metaphysical unity, as soul and body of the same unit of movement. The automobile is the technical double of the transcendental subject, active on principle. (…) It is the reason why the automobile is the sacrosanct object of modernity, the cultic center of a universal kinetic religion, the sacrament on wheels that allows us to participate in what is faster than ourselves. Whoever drives a car approaches the divine, he feels his diminutive self expanding into a higher Self which gives him the homeland of the whole world of fast roads and which makes him aware of the fact that he is destined to a life superior to the semi-animal existence of the pedestrian.” Peter Sloterdijk, La mobilisation infinie: vers une critique de la cinétique politique (Paris: Christian Bourgois, 2000) 38-41. Free translation.

6 Ibid.

7 André Lepecki, “Coreopolítica e coreopolícia,” in: ILHA. Revista de Antropologia (Florianópolis: Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina -UFSC, 2011) 48. https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/ilha/article/view/2175-8034.2011v13n1-2p41/23932 [Accessed November 2018]

8 Two important artistic references concerning autoimmobility for me are: Milton Machado’s Edifício galaxie (sobre a mobilidade), 1975-2002 and Wolf Vostell Ruhender Verkehr, 1969, definitively installed in one of the Colônia’s avenues in 1989. Cf. https://nararoesler.art/artists/52-milton-machado/#top_nav https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruhender_Verkehr_(Plastik) [Accessed Februrary 2018]

9 In the mid-2000s, beginning with policy debates about sculptures in the public spaces of the city of Rio de Janeiro, I began to formulate a proposal, never completed, to install Clóvis’s car near the large intersection of Av. Americas with Av. Salvador Allende, on the boundaries of Barra da Tijuca. It was to be installed in one of the flowerbeds that divide the high-speed tracks. For a long time I had observed there the anonymous cultivation of a small flower garden, just as crosses and flowers mark the memory of their dead on Brazilian roads. A counter-monument (in contrast to the landscape of buildings and avenues of Barra da Tijuca) in honor of the victims of traffic – in a double sense: those who suffer there because of the speed of cars and/or displacement processes due to urban/road networks.

10 For more information on this and other works by Clóvis see: Livia Flores, “Sentado al selado eu sorria: os trabalhos e os dias com Clóvis” in Revista MODOS – História da Arte: modos de ver, exibir e compreender (Campinas: Unicamp, May 2018) https://www.publionline.iar.unicamp.br/index.php/

11 Closed definitively in 2004, I do not know if it was by irony or the hand of Ártemis, [the Model Farm/Fazenda Modelo] re-encountered its vocation as a shelter for mistreated animals in 2008.

12 This trajectory follows that of artworks and not one of psychological diagnosis. In 2005, when I became acquainted with the mBrac’s project of integration with contemporary art, I contacted the then director Ricardo Aquino and curator Wilson Lázaro, who were interested in hosting the works that had been exhibited at the São Paulo Biennial. These remained Clovis’s [artworks] (I chose at the time to divide the fees instead of acquiring them) and unfortunately “got lost,” according to Ricardo Rezende, the current curator.

13 For more information see FIOCRUZ website: https://portal.fiocruz.br/en/foundation

14 [Editor’s Note E.N.: Vila Autódromo – a former fisherman colony and small village were approximately 500 families lived at the edge of the Jacarepaguá lake which was expropriated and used for what today is part of the Olympic park. For information on the struggle of families to remain in the area see the dialogue section of this magazine: http://institutomesa.org/revistamesa/edicoes/5/portfolio/maria-da-penha-macena-luiz-claudio-silva-e-luiza-andrade-en/?lang=en]

15 [E.N.: The TransOlympic Avenue was constructed for the Olympics and Paralympic Games of 2016. Its construction caused the destruction of 200,000m² of Atlantic Forest at the limits of Pedra Branca State Park, the second largest urban forest in the world. It cost about 270 million dollars and in a violent and arbitrary way divided the territory of Colônia Juliano Moreira into two parts. Under the avenue, today, a small tunnel is the only link between mBrac and the Polo Experimental.]

16 [E.N.: Administered by mBrac, the Polo Experimental is a community, educational and cultural center, that via the idea of togetherness, integrates cultural actions in the Colônia in an old remodeled Pavilion transformed to house: the activities of Escola Livre de Artes [Free School of the Arts – ELA]; Casa B [Home B – artistic residency]; Atelier Gaia; the income generation project Art and Garden Company and the leisure program Pedra Branca (White Stone). http://museubispodorosario.com/polo-exp/o-polo-experimental]

17 Amongst the Ateliê Gaia artists only Clóvis, Arlindo and Luiz Carlos had works in the Lugares do delírio exhibition. Their works were presented independently from those produced by the artists in residence.

18 I borrow here the use of the word “outside” as a synonym for meaning far away from the city, as I often heard the family from the interior of Rio Grande do Sul refer to their house of origin in the Pampas Gauchos [region of grasslands in the southern most Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul]. But it also encompasses a sense of being “outside” of the city even when being in it. The life of the cars. “With your headlights on, I think it’s so beautiful.”

19 Verdelinho is the name of a bird adopted by a musician from Alagoas known as Mestre Verdelinho (1945-2010). Clovis sings of “verdelinho” [T.N. verde in Portuguese means Green and “inho” is a diminuitive meaning little] which I have tentatively deciphered as the “little green man” and as a reference to the musician Verdelinho.

20 Excerpt from music composed by Leonardo Lobão, with the collaboration of Leandro Nunes and Emanuel Flores.

21 In the context of the exhibition Lugares do delírio, Clovis’s car, the standards of Patrícia Ruth (2), Leonardo Lobão (4), Pedro Mota (1), Clovis (1), the hand props of Luiz Carlos Marques, Arlindo’s mask and the clothes prepared by the Polo Experimental sewing studio, were integrated into the project carro alegórico. All were combined for a special Carnival presentation under the pilotis (covered patio) of MAR on February 11th, 2017. This event brought together two Carnival “blocos” linked to anti-asylum struggle: Império Colonial from mBrac and Tá Pirando, Pirado, Pirou [You are having a crazy fit, are crazy, had a fit] from Instituto Philippe Pinel. The car/float left the shed where we had been working up until February 10th and returned there the next day, along with the other works and objects to the mBrac / Polo Experimental. This ensemble remained on exhibition in the entrance hall of mBrac over the course of several months.