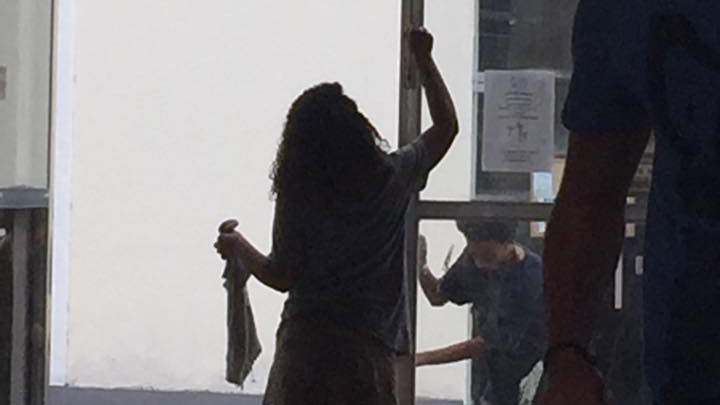

Students cleaning the school during the occupation of the High School Colégio Pedro II. Source: Ocupa CP2 Real Available: https://www.facebook.com/ocupaCP2real. [Accessed October, 2018]

Corridor-School: Toward a Poetics of Occupation (in Two Voices)

Isabella Dias

Luiz Guilherme Barbosa

As long as I write and talk I have to pretend that someone is holding my hand.

Clarice Lispector 1

I think about how much more seductive it is to continue in the hallways where I chat informally with staff about what they did over the weekend, which buses they get, and stories of their teenage years. Here they are like me. In the hallway, I humanize them and now, when I stop to analyze these exchanges, I see poetry in them.

*

School happens more in the hallway than the classroom. It can often be like this, when talking and living together seems at once a pair that is an enemy inside the classroom and a friend outside of it. In a hallway between classes, in a hallway before or after school, in a hallway during the break, any informal conversation can reveal something in common between a student, teacher, inspector, or principal, the same bus line they take to get to school, the movies they saw on the weekend, some childhood memory. In these astonishing dialogues, it’s somehow delightful to realize that the teachers, like the students, eat strawberries for breakfast. Each one prefers one route to another, one song to another, one banality over another. The hallways, symmetrical to the classroom, liberate a pedagogical energy that the classroom has bureaucratized.

But even this is not enough because when we get together and talk, it becomes clear that we need to work with urgencies. Janitors, security guards, cooks participate less in the hallways of a school, which make up a frontier between the knowledge of the classroom and the knowledge that does not circulate in the hallways. The school hallway is a boundary between curricula, between knowledge deemed worthy of being taught, and those who are left out of the learning process as instituted by society and the state. The knowledge that does not participate in the school curriculum nor frequent the hallways comprises practices of care: care of food and nutrition, care of cleanliness and hygiene, care for property and safety. Cooks (almost always women), security guards (almost always men) and janitors are almost always black. Former Pedro II College student, currently at university, Mariana Oliveira, named these know-hows and knowledge practices as “the black pillars.”

*

Criss-crossed words and speech taught me very early on that school is the hallway, with its encounters, dynamics and interactions. At the same time I remember that it is the spring of knowledge – if you want to bustle, go out there. Here is the classroom. In my day, it did not work like that, in my day there was respect, in my day – and I blame my time for not being like that other time that adults refer to. Back in day, I do not know which, where things were better, when surely I would not feel this enormous desire to make of this space nothing other than the stage for my dances, reflections, songs, and touches distributed among those that share this space. I think about how much more seductive it seems to me to continue down the hallways where I converse informally with staff about what they did over the weekend, about the buses they get and their teenage stories. In these astonishing dialogues, I find myself completely delighted by the prospect that they, like me, eat strawberries for breakfast.

*

I began to realize the importance of the school hallways after I became professor at Pedro II College and, two years later, when I met Isabella Dias. Isabella was not my student. We met via a special junior academic initiative: she was competing for a scholarship to join a group of students who were part of a training project that I helped organize alongside other fellow professors in 2016 and 2017. Throughout the year, Isabella and fellow colleagues participated in a course organized around different genres of text and modes of academic research: workshops focusing on how to write or review a text, to put together a bibliography, and to write an academic article, and to consider the elasticity of the essay format according to the research they wished to perform. For the project, Isabella suggested the idea of researching the secondary school occupations as a form of cultural production, and from there on we began to study together.

Since then we have established a relationship that has been woven in the hallways and in the courtyard, between one class and another. Such research activity in a school context represents the recognition of the hallway as a frontier space of the curriculum. It is in encounters outside the classroom, yet still in the school, in the context of a pedagogical relationship freed from the temporality of learning that a classroom requires, such as via a long-term research project, that another school may emerge. And this became even more the case when, at the end of that year of 2016, the students, in assembly, and resisting the proposed cuts of Michel Temer’s sad government, decided to occupy the Realengo campus of the Colégio Pedro II. The occupation did not just postpone the research work we had been developing, it rather brought the object of research into the everyday of school life, and Isabella participated actively in the two months of school occupation.

*

It was in samba sessions, funk choreography and rap festivals that my generation experienced a re-encounter with their subjectivities. This re-encounter awakened in young people the prospect of a pleasurable life, transforming us from an expressionless and subordinate figure to an autonomous figure in charge of him/herself. The opposite of practices of punishment, silencing and violence, the bonds established through affective experiences cannot be acquired in the sterility of schools or universities. On the contrary, they promote the autonomy and liberation necessary to return to the process of discovering one’s identity. The awareness promoted by subversive affectivity is that self-recognition will only be possible as a joint trajectory, one of respect and preservation of the other’s singularities.

The composition of an identity becomes real when, through love, equilibrium is established. Art as demonstration also signifies manifesto and assumes a maternal character, one of orientation: like a mother, art reveals the paths without, in this way, taking us away from the elaboration of our own course. Through art and free from the bonds of rationality, we seek to know in places, with people, via touch, experiences that discourse is not capable of conferring alone. In this way, we do not separate ourselves from the world to understand it, we rather live in the world so that within it, we can feel and narrate it.

Engagement through the work of art – and the work of love – is the most democratic way of learning. We love the other because it is inevitable, we love him or her because there is exchange and love is the only way to respect and value. This love is as much about giving as receiving, without this exchange exhausting one or the other. Here, there are no hierarchies. With this affective (and as such) revolutionary perception, the occupation of schools – of public spaces, without the organized routine promoted in the house of the parents – removed itself from a utopian possibility to become a real proposition, constructed daily by the students.

*

Fig. 1 Creating banners and other various productions in the school space. Source: Ocupa CP2 Real Available: https://www.facebook.com/ocupaCP2real. [Accessed October, 2018.]

Word spread. Different forms of spoken communication circulated the secondary school occupations of 2015 and 2016. There were bands, interviews, hair stories, fake news, sentences, fractures, games, speeches, songs. Or songs of war. “Mum, dad, I’m in the occupation, and just so you know I’m fighting for education.” Songs for a community affiliated to the school, for mothers, fathers, myself, hymns filmed by a social networking community, funk parodies that we wanted to demonstrate. “The governor says he has no money, you can bet it’s in the contractor’s pocket.” An occupation is performative. For this reason occupations need a chorus of voices and bodies. A school occupation also produces curriculum: teachers and others offering classes, workshops, assemblies, public lessons. This opens up via etymologic lesson of the word “curriculum” and the word “course,” a path for learning catalyzed by the erotic urgency of the choir: to produce and affirm black, feminine, transgender, and peripheral bodies against terrorist explosion of bodies, against the state implosion of bodies.

An occupation lasts based on knowledge practices and know-hows traditionally exiled from the classroom, knowing how to clean the school, how to feed the school, how to keep the school safe. They are black pillars, functions more often than not performed by black people, underground know-hows that, in the gesture of occupying, loom large and urgent, demanding students act as security guards, lunch organizers, general service aides. And an occupation lasts while know-hows alienated from teaching become an uncontrollable demand: how to care for the school, its institution, its community. There, students are part of the school body, and produce – as the indigenous peoples are part of the body of the land, with the forest – the right to occupy it.2 What an occupation lays bare: such know-hows are untranslatable to a body, which for this reason occupies, or rather: such know-hows are what is an untranslatable quality of bodies.

*

The students only got to know who served lunch when, not as part of the established daily routine, but in the day-to-day of the occupation, they were taught to cook. They only got to know the cleaning staff when the students took care of cleaning the space. They got to know the gardeners were when they were taught the name and function of plants and flowers, a knowledge that they did not acquire in school, nor university, but through work. The intersections of these knowledge practices and know-hows spurred interest and the search for what had not yet been discovered. Paths foreign to artistic expression built the struggle of resistance in that territory. The care of space was cultivated by esteem, which substituted daily duty. In an inaugural way, the school carried out peripheral and popular social practices in a teaching-learning context. Talks about candomblé, workshops of poetry and jongo [T.N. Afro-Brazilian oral storytelling tradition], debate sessions on sexuality and samba, rap improvisation, parties, funk fairs, all happened right there in the school, a context that often marginalizes all these manifestations. The body. Art included repressed and invisibilized bodies, in a profound and inescapable process of humanization. The oddity of seeing a student without their uniform in the school environment had the force of a street protest. The community. In a secondary occupation – as well as in university occupations – the entire surrounding community moves with it.

*

An occupation speaks about bodies because an occupation also connects to social networks, the new modes of communication in digital media. The occupations were sustained by those who were born digital, for whom the intimacy with the image of the body of the other, and of their discourse, seems out of date with the social norms of erotic relation in the day to day of the present body. It is necessary to understand the defense of occupation as the production of a political subject alongside other political subjects, one among others, where each one, is “an ‘each’ who turns into one but is still each”, to use the formulation of Mariana Freitas, another student of the Colégio Pedro II. One text that was very important to us in our research, a reference to which at times we drew ourselves closer to and at others, distanced ourselves from, but with which we agreed when the subject was the analysis of social networks in the context of political resistance:

Before you can actively communicate in networks, you must become a singularity. The old cultural projects against alienation wanted the return of you to yourself. They battled the ways in which capitalist society and ideology have separated us from ourselves, broken us in two, and thus sought a form of wholeness and authenticity, most often in individual terms. When you become a singularity, instead, you will never be a whole self. Singularities are defined by being multiple internally and finding themselves externally only in relation to others. The communication and expression of singularities in networks, then, is not individual but choral, and it is always operative, linked to a doing, making ourselves while being together.3

The tactic of high school occupation produced a context similar to an early political warning. This century is another, cry the young people born in this century. And from there, this cry inscribed itself within social networks as if a song of war (it was to protect themselves that the occupations maintained committees responsible for the social media of the movement), these musical forms echoed, singing funk, for example, as if the funk had been composed in an occupation. Like the actors from Martins Penna State Technical School of Theater, Rio de Janeiro, performing on the steps of the Legislative Assembly of Rio de Janeiro, on March 9, 2016, who sang “Baile de favela” [Favela Dance] by MC João, with reworked lyrics “You want to read books, you think you deserve it, you want to go to the theater, you think you deserve it, you want to go to the movies, you think you deserve it”, over the part: “She came hot, today I’m on fire”, which is almost the same as “You can come hot as I’m on fire” from 1967, sung by Erasmo Carlos. From translation to translation, the text remains provocative, in favor of the voice, of assuming voice as a taking on of culture, occupying them, like the Jovem Guarda [T.N Literally Youth Vanguard – 60s pop music followers] of the occupations, mediated by funk, but with a difference: the occupants’ war song stages an enemy voice. In chorus. It’s a problem of translation, one might say.

*

The occupation eventually fell victim to the expected exhaustion. However, the return to routine proved to not only be harrowing but also frightening. Its unpredictability turned into anxiety. After numerous bureaucratic processes in which the institution recorded the changes made on campus by the occupants – from the painting of a room to the installation of a stove – , it was necessary to think of ways to translate the transformations experienced during the months of political-pedagogical experimentation into the established routine of the school space. “Translating is like looking right and left at the same time,” as Caio Phillipi, a college student, defined when he was challenged in the first post-occupation class to literally translate Bartleby’s formula: I would prefer not to.4 A kind of post-occupation exile was established next to the new order, at least new in theory. We heard from the director, the dean and representatives of the school’s big bureaucratic positions that we must find suitable ways to translate the learning of occupation to the reality of the College, which sounded enormously offensive to us. We tried to take on this translation as a possibility, but we know that translating is almost impossible. Bodies become language. We communicate with bodies because they produce knowledge that does not fit in textbooks. I do not want the occupation to become exclusively the object of university theses, running the risk of burying these phenomena as they analyze them, connecting them to the past. We won’t give up.

As occupants, we insist on not giving up because there is no middle ground when discourses are antagonistic. We were accused of utopia, and we listened impassively. We laughed and we exiled ourselves, but in this immaterial community we shared the power of what we were living. Here, exile becomes an experience of de-eroticization. Bureaucrats tried to turn exile into guilt, without efficacy. Stifled know-hows, ones without curriculum, came to the surface, and in turn expanded. It is not possible to point toward a way back. There is no turning back. As a young person, I think about democracy, I think about education, I think about politics and I think about affection, and the ideas do not seem very organized, but they sound reasonable when I talk to other people at school. This is how a thought encounters an unexpected collective recognition, by speaking. And this is the first gesture of an occupation.

***

Isabella Dias

Isabella is a student of the Pedro II Campus Realengo Campus and was active in the occupation of her school. Since then, it has been proposed to think of students and their relationships from a affective, in an attempt to understand their relationships as a pedagogical process.

Luiz Guilherme Barbosa

Luiz Guilherme is a poet and teacher at the Pedro II School of Realengo. He actively supported the occupation of the school by the students and his currently developing an outreach and research project related to the occupations.

______

1 Clarice Lispector, A paixão segundo G.H. Paris: Association Archives de la littérature latino-américaine, de Caraïbes et africanique du XXe. Siècle; Brasília: CNPq, 1988., 13. (Coleção Arquivos; 13).

2 Writing based on the secondary school occupations Alexandre Nodari draws a parallel with the students’ tactics and the rights of Indigenous peoples’ occupation: “It’s not about a relation of property but reciprocity, a reciprocal property: if, as Eduardo Viveiros de Castro affirms, ‘Indians are part of the body of the Earth’, they participate in the earth’s body, and for this they have the right to occupy it.” Alexandre Nodari, “Ocupação e cuidado” [Occupation and Care], 2016. [https://partessemumtodo.wordpress.com/2016/10/09/ocupacao-e-cuidado/)

3 Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Declaração – Isto não é um manifesto. Translation Carlos Szlak. São Paulo: n-1 edições, 2014, 57. From original text Declaration: This is not a Manifesto as cited: https://redefineschool.com/michael-hardt/ [Accessed 19 october, 2018.]

4 In Bartleby, The Scrivener (1853), Herman Melville’s story features the refrain, “I would prefer not to,” which is repeated by Bartleby with variations, such as “I prefer not to,” responding to his employer’s demand for labor. The (un) translatability of the proposition was studied by Gilles Deleuze (“Bartleby, or the formula”, 1993) and tested in a paper proposed to high school students at Colégio Pedro II, who proposed solutions such as: “I would rather not” I would appreciate not doing it,” “I would opt not to,” “I’d choose not now,” and “I would like not to. “