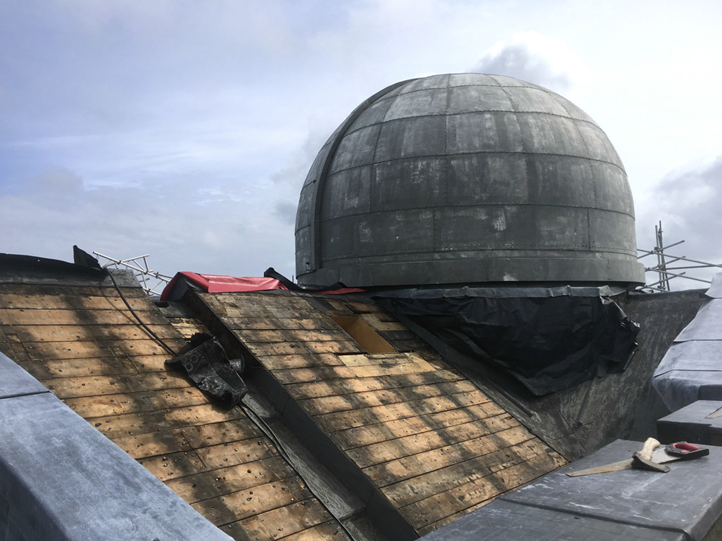

Restoration of the City Observatory begins and the foundations are laid for the new gallery, 2017

Instituting for Collaboration and Care

Kate Gray, Director of Collective, Edinburgh

Collective is a small visual art organization based in Edinburgh, Scotland, whose primary role is bringing people together to produce new work with and for artists. This entails much “backstage” work with artists, groups, constituencies, specialists and communities as well as the “on stage” work of presenting these initiatives to publics through exhibitions, events, workshops, and other projects formats. We are currently instituting a new iteration of the organization, through the redevelopment and reimagining of the iconic Old City Observatory on Calton Hill – an Edinburgh landmark overlooking the city.

During the process of redevelopment, we have set out to re-evaluate our organizational methods. This text will look at the organization’s move to the City Observatory and recent co-authored and collaborative projects including: Satellites Program; Constellations Program, specifically a current project between Petra Bauer and a local charity called SCOT-PEP; hosting the Social Reproduction Reading Group; and experimental evaluation projects with artist Shona Macnaughton, as well as touching on other artists’ research projects. I will trace our organizational learning and how we seek to collaborate with artists and other constituencies to develop it. Through this, we have uncovered a relationship to care by articulating the value and specific capacities of small-scale visual art organizations’ that employ care as a method.

Connecting Backstage & On Stage: Care as Practice

Care is often referred to as being devalued in contemporary society. As art is a reflection of society, perhaps it might be extrapolated that care is devalued in art organizations. At Collective, care is the opportunity to host and to listen. We are actively engaged in a conversation about how a new iteration of our art organization might actively institute with care as a value. How might the organization provide the context in which care is valued and fostered as a precondition of attentive listening and trust?

This is not the kind of care which might be represented as over cautious or as carefulness, but the kind which aims to value concerns of others and asks what might be done, what might we host or produce together. Collective is an organization that reflects on and values the ‘backstage’ of all forms of production and the inherent link between what happens ‘backstage’ and what is visible to publics in the ‘on stage’ of the exhibition space or other contexts of making public. Things can be invisible because they are structurally undervalued. As an organization that makes things visible through presentation, one of the things we feel the need to particularly reflect on are these ‘backstage’ areas.1

Histories: A Complex Panorama

Collective was initiated by artists in 1984 to address their need to see, show and take part in the world beyond their studio walls – to be a platform for artists. There was an impetus to embrace change and learning, through both making art and making ideas public. This artist-led DNA is still at the core of the organization. However, Collective has grown and changed, responding to the environment in which it finds itself. Never standing still, learning is at the heart of what the organization delivers. Through many structural iterations, numerous artists and staff teams, the organization has responded to change and developed to meet the needs of different times. I have been Director at Collective since 2009, and in this time, we have evolved again moving to the City Observatory on Calton Hill, a site which is best known for being a great vantage point to view the city of Edinburgh.

Built between 1800 and 1880, and sitting within a walled garden, the Old City Observatory was once a working astronomical observatory, initially used by mariners to set accurate time to navigate the globe. It is a significant icon of the Scottish Enlightenment and resonates with complex, entangled histories conceived in this period, including arguably the birth of capitalism itself. In 2010, it was in a bad state of disrepair and under threat of utter demise with no clear plan for its future. Collective became involved in the development of the City Observatory after producing a site-specific project with artists in this site in 2010. Conversations began about how this location, which is held in the common good by Edinburgh City Council, might be reimagined to become a new kind of observatory for the city.

Our challenge is to redefine the City Observatory that historically housed telescopes to observe the stars, mark time and facilitate effective trade routes. What would a new kind of observatory look like or do? How could Collective create a space imagined as laboratory in which to follow experimental, creative or academic pursuits orbiting around visual art? Calton Hill is an enigmatic site woven into multiple times, spaces and narratives. For example, 18th century painter Robert Barker conceived the concept of, and the word, panorama in 1787 while walking on this hill. These complicated layers of history underpin it as a place for artists, constituencies and audiences to view, to reflect upon the city, to draw people together, to research, and to make work.

Through the production of new art work and drawing people together around mutual concerns in our contemporary socio-political landscape, we will ask: How can the organization foster and value care? This becomes especially challenging when we understand the site’s links to colonization. Can Collective decolonize this site, which is entangled with an often white, male, scientifically legitimized system of thought that was born from the Enlightenment and Imperialism? This question was addressed by curator Simon Sheikh when he wrote the text ‘A Contemporary Observatory for the City’ in our 2017 publication Towards a City Observatory: Constellations in Art, Collaboration and Locality: “Our current task, then, is to decolonize the observatory, precisely by making its foundations unstable, its production of knowledge a zone of contact. The observatory must engage in uncertainty rather than scientific assessment, or bureaucratic benchmarking.”2

Exchange of Method: Decolonization, Learning and Unlearning

Embarking on the cross-cultural initiative An Exchange of Method, between Rio de Janeiro and Edinburgh, was an opportunity to reflect on how this exchange might have meaning for Collective and our wider interest in decolonial practices, learning and unlearning. As an organization, we find ourselves drawn to institutions and individuals who actively reflect on the context in which they are operating and embrace the uncertainty of this. There are also added complexities of thinking about decolonization within an exchange project between Britain and Brazil, which if studied deeply here, could create a whole other text.3 This exchange sought mutuality between organizations that engage with their locality, by either drawing people towards them or looking outside their walls. To me, this holding of space and uncertainty is a mark of caring for both individuals and organizations and their localities.

On an initial research visit to Rio de Janeiro in 2015, I was introduced to the work of the collective Norte Comum4 through their residency at Centro Municipal de Arte Hélio Oiticica.5 Norte Comum (Common North) brings together artists, cultural producers, videographers and others from different areas of Rio mainly operating in the North Zone of the city, with the primary aim to promote circulation in and use of public spaces as a zone of contact. They aim to create possibilities for exchange that are not ruled by capital and power relations. By using public space to hold meetings and provide different types of cultural events and artistic interventions, particularly outside of traditional prescribed cultural spaces, they develop new connections.

Norte Comum at Hotel Loucura, Rio de Janiero, Brazil, 2014. Courtesy the artists and Hotel Loucura.

Norte Comum’s projects have been carried out as an independent collective, but has often been facilitated by institutions such as SESC, Instituto Municipal Nise da Silveira or small organizations such as the Hélio Oiticica Municipal Art Center. This demonstrates the importance of small-scale art organizations and the producers, curators and directors who work within them of spotting and supporting grassroots movements with care. Collectives like North Comum need to maintain a position outside the institution. However, it is arguable that there needs to be an element of support –and small-scale organizations may be able to offer a community of ideas that can give stability without colonizing the group.

Many of the collective members met through working as producers in the NGO Observatório de Favelas [Favela Observatory], an organization which focuses on research, consulting and public action dedicated to the production of knowledge and policy proposals for slums and urban phenomenon. This first visit to Rio and meeting the Norte Comum collective was, in many ways, an initial backstage encounter that grew to be a larger project.

We were honored, along with Artlink, to host Jefferson Vasconcellos from Norte Comum and Izabela Pucu former director/curator of Centro Municipal de Arte Hélio Oiticica in Edinburgh in November 2015, where we continued a dialogue and exchange between artists and organizations initiated a month earlier in Rio de Janeiro. Our interests coalesced around those who explicitly or implicitly work with practices and methods between people, groups and bring into focus individuals or narratives that are often invisible through habit and assumption. This we broadly understood as care. The aim was to, by exchange, develop our understandings of our own method and that of others, and the particularities of these methods to work towards a different way to embody an institutional habit of care.

An Exchange of Method ran in parallel with Collective redeveloping the City Observatory to be a new kind of observatory for Edinburgh. A vital aspect of this building project was to also document and evaluate the process. Collective has an ongoing interest in experimental evaluation and had previously commissioned an evaluation of a major public project called Somersault by Julie Crawshaw,6 a Lecturer in Art and Design History and an art anthropologist. Julie’s evaluation was produced uniquely from her perspective as a researcher who works in tandem with artists, planners, community members and others. Her research explores human and non-human relations towards making future plans.

Evaluation is often directed at participants in projects undertaken by marketing and development departments of organizations to record both quantities of participants and the quality of the experience. These are often recorded through leading questions that target the “self-confidence” or “employability skills” developed. However, artists and others have used “institutional critique”7 as a touchstone to an alternative understanding of evaluation. Andrea Fraser’s important work Museum Highlights, 2005, identifies that “if there is no outside for us, it is not because the institution is totally closed… it is because the institution is inside us.” This has led to approaches and interventions, performative gestures and language intended to disrupt the otherwise transparent operations of galleries and museums and the professionals who administer them.

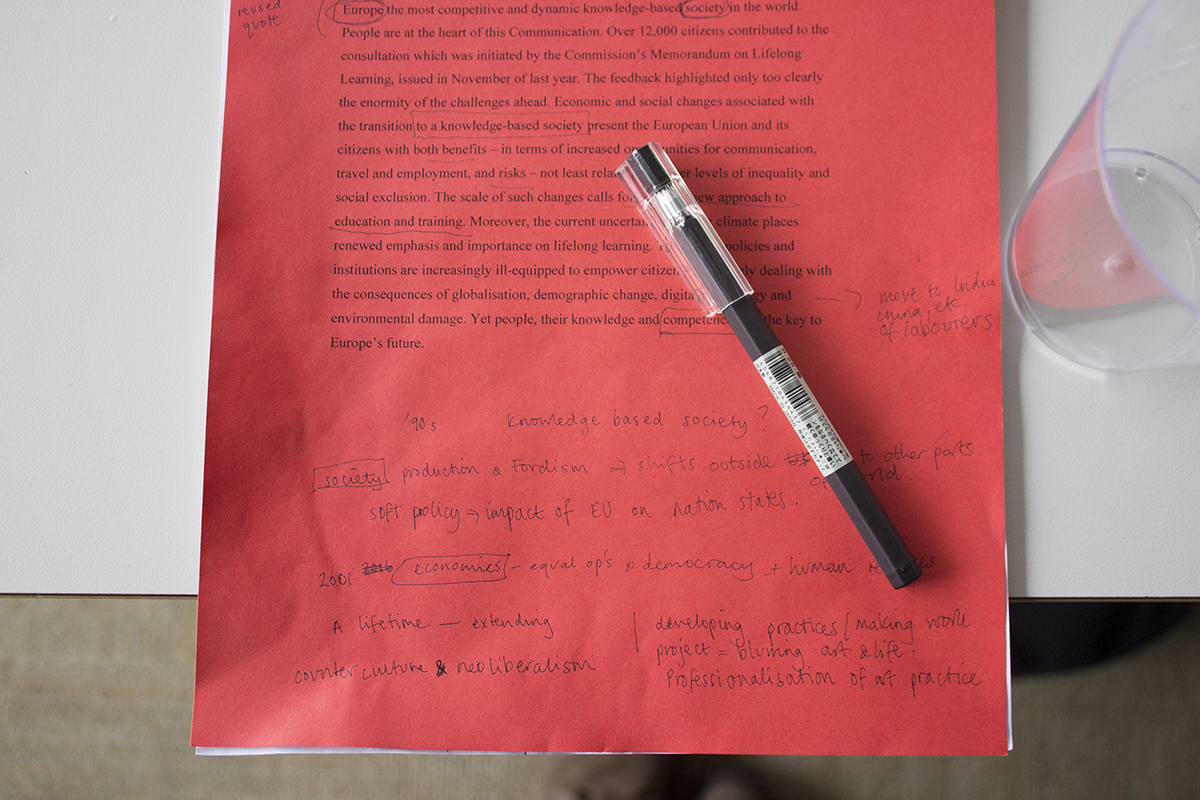

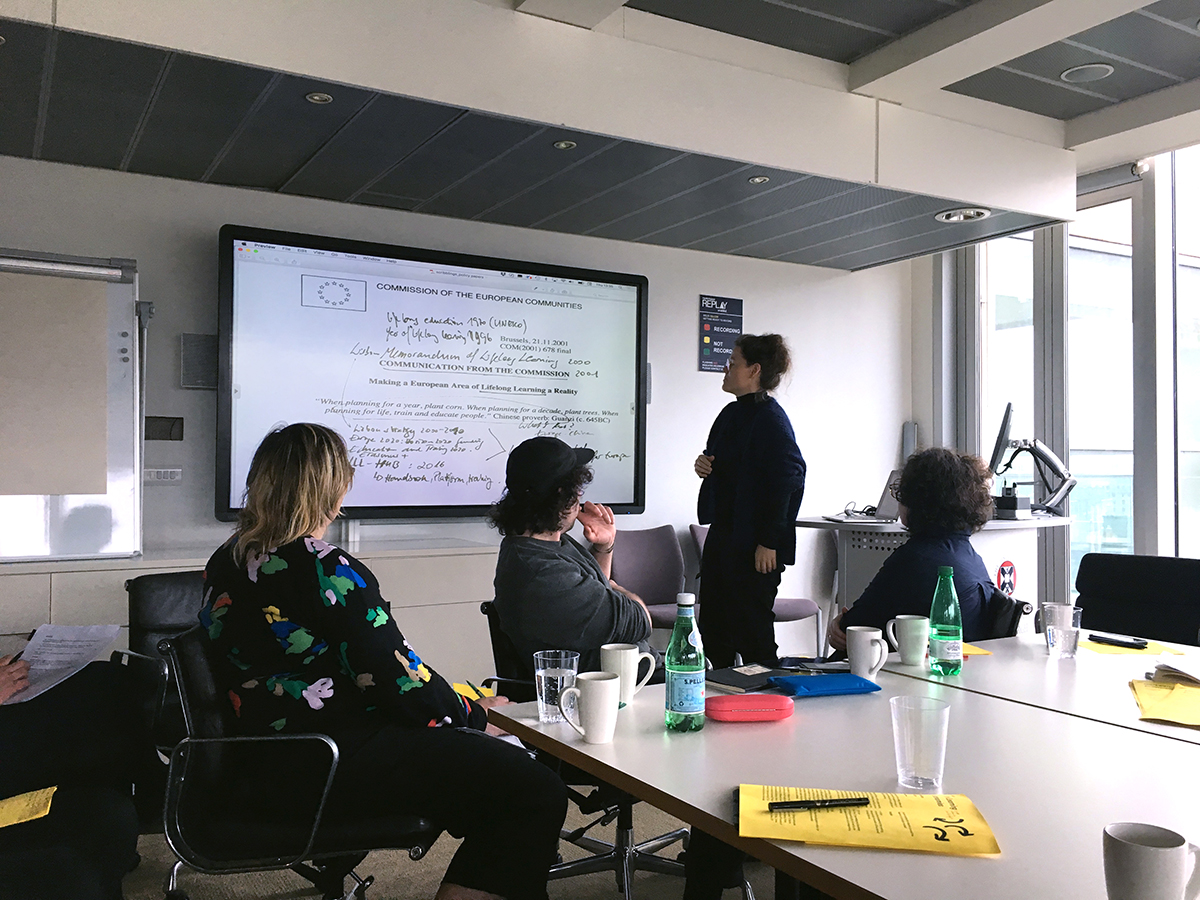

How do we understand evaluation in this context? Collective planned to commission a new experimental evaluation of the redevelopment of the City Observatory, drawing both on past evaluation and institutional critique. We approached artist Shona Macnaughton8 whose practice is rooted in performance, writing and film. Her practice questions technology, subjectivity and labor, often involving staged re-enactments, performative scripts and actions set up to confront an audience. She uses a method of reframing texts relating to the site of display, transferring them from their original context onto present political and technological conditions.

We commissioned Shona to perform an experimental evaluation of the organization as it progressed through the structural changes of instituting a new space. Her work, which is responsive to specific political conditions and architectures, and both physical and virtual space, has been devised to question how the changing language and design of Collective relates to notions of care. As part of this process, Shona was invited to take part in An Exchange of Method as the two projects were seen as linked and provided an additional opportunity to reflect on organizational practice. She produced a text, a version of which is included in this publication, which speaks for itself.

Shona’s participation in An Exchange of Method in Rio in late 2017 also brought together notions of social reproduction, the performance of care and institutional reflection. Shona was pregnant with her second child when she was in Rio and this interestingly highlighted issues that have been made explicit by social reproduction (which I will address later) and implicit in practice-led enquiry that draws on subjective, interdisciplinary methodologies. It is perhaps therefore, unsurprising that Shona found a strong connection with Millena Lízia, an artist based in Rio who critically addresses her Afro-Brazilian roots, the legacy of slavery and how it continues to manifest itself in domestic labor. Using ordinary objects and everyday situations to think about the connection between the subject and the environment, Millena uses her body (and its subjectivities) in performances with environments where habits are performed or displayed. Exploring the relationship between micro and the macro, the organic and the inorganic, it makes explicit the passing performances of daily life.

Together Shona and Millena began an exploration of their interconnected work and methods. Cleaning, bearing children and their relationship to social reproduction, instituting and colonization is an area which is explored by the exchange between the two artists, also published here as an email conversation. Between these texts and approaches, we can see in action the practice-based enquiry and shifting methods of artists who highlight the habits of care, especially in organizations. In relation to gender and race, these practices underpin informal or tacit knowledges which we perform every day. These works and conversations provoke us to reflect on and question our everyday performance of care, and the values that underpin it.

Embracing the Uncertainty of Unlearning

What has grown out of many of the encounters within An Exchange of Method is a need to reflect on education, both formal and informal, and how we embody it through performance and gesture. Reflecting on the process of learning in the context of decolonization, a necessary relationship between learning and unlearning emerges.

Artist Annette Krauss9 has developed a research practice based on her understanding of the possibilities of unlearning. In her work Sites for Unlearning Annette speaks of “a series of collaborations, experiments, and conversations that have at once grappled with and shaped the material, artistic, and political dimensions of unlearning processes.”10 Her work understands the term “unlearning” as coming from social movements, alternative education, feminist, post-colonial and decolonial theory and in particular the work of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, in relation to “check your privilege.” The phrase has become ubiquitous in online debate, but aims to address the need to positively unlearn privilege, its gestures, performances and institutions, in order to learn a new way to perform in the world.

Annette’s research has informed Collective’s learning program, articulated by James Bell, who also took part in An Exchange of Method as a producer from Collective. As unlearning is at the heart of our interest in decolonization, Collective have developed an approach through seeing learning and unlearning as intertwined. An invitation to Annette Krauss to visit us to help develop our understanding of our institutional practices and the relationship between unlearning and collaboration is ongoing. Our program values are concerned with how learning and unlearning go hand-in-hand and how we can bring different forms of knowledge into education environments, which can be hard for teachers in formal education to address. Furthermore, our learning program aims to provide a different route to generate new understandings and forms of knowledge through the production of artworks. It is because of the strong connections we seek between learning, collaboration and care that James Bell took part in An Exchange of Method. The exchange process fostered engagement with the shared practices and methods of learning and unlearning, and the resonance with the concern of decolonization.

Artlink speaks of changing learnt behaviors between staff, clients and artists. James reflects on the resonances between his own work within Collective’s schools program and the reflections of Rio-based high school teacher Luiz Guilherme Barbosa and student Isabella Dias and their engagement in the 2016 ‘occupation’ of their school. His essay also touches on ways which Annette Krauss’ on-going project The Hidden Curriculum has helped inform our work. In The Hidden Curriculum, pupils work with Annette to address tacit forms of knowledge and habits in learning, pushing the boundaries of the participants and organizations’ through experimental gatherings aiming to unlearn collaboratively.

The connections between artists, institutions, methods and practices initiated and sustained through An Exchange of Method are strong. Our shared experiences form new understandings and habits, though we are conscious that our histories are very different. I have been very aware of the European dynamic; Brazil was colonized by Portugal and Britain is/was a colonizer. The very funding which allowed for this exchange, from the British Council, might be described as complicit within this history. Therefore, it was important to have a focus on how collaborative unlearning might facilitate a negotiation of these different histories. There are interesting parallel histories of radical pedagogy between the two countries including Paulo Freire, the Brazilian educator and philosopher who was a leading advocate of critical pedagogy, and Scottish thinkers such as R. D. Laing, a psychiatrist who wrote extensively on mental illness.

Laing’s views on the causes and treatment of mental health were greatly influenced by existential philosophy and ran counter to chemical methods.11 He took the expressed feelings of the individual patient as valid descriptions of lived experience, rather than simply as symptoms of mental illness. This has been influential to the development of patient centered work. Freire is best known internationally for Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which has become a touchstone of critical pedagogy.12 His notion of the “practice of freedom,” as a means by which people deal critically with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world is pertinent in many current practices, including those of artists involved in these exchanges. Equally, Freire drew attention to informal/tacit knowledge and the importance of the interrogation of the systems of dominant social relations, which he posited created a “culture of silence” – a practice that leads to what we now be understood as a culture of invisibility. Many of these histories and discussions are important to the organizations involved in An Exchange of Method.

Commissioning Artists in a Context

Collective commissions new work from over nine artists per year, working with and for artists and constituencies to produce and present each project. We work with international artists to commission their first project in Scotland and a cohort of emergent, Scotland-based arts practitioners each year through our Satellites Program. Selected from an open submission by a new panel each year, Satellites Program has been specifically developed to facilitate practitioners at a pivotal, emergent point in their career. Once on the program, artists and associate producers are supported through a structured program of retreats, workshops, studio visits and group discussions, currently facilitated by the artist James N Hutchinson along with Collective staff members Frances Stacey and Siobhan Carroll.

Informational video about Collective’s Satellites Program.

The analogy of the “backstage” and “on stage” is useful to describe this program; the small publically visible “on stage” exhibitions are public, but the far the larger invisible “backstage” of workshops, discussions and retreats leading to an experimental peer-led development program is an important invisible platform. It is often the case that this intensive concentration of resources in a few artists per year is unsustainable, but this is the very foundation of the organization and generative core of the program. Through the process of getting to know artists’ practice so intimately, there are often repercussions in following years. It is not a coincidence that Shona Macnaughton was one of the cohort in 2013, as the care which is inherent in this program informs all others. Collective broadens out our working practices to connect to constituencies, schools and other parties. We aim to draw people together, but always with attention to the specifics of each encounter. We do not claim to always get things “right” and failure is an opportunity to unlearn mistakes. So we aim to consistently challenge ourselves and others, to understand what might be possible, through making these opportunities open.

The possibilities of developing meaningful, mutual ways of working within our locality has led us to develop a strand of programming which we call Constellations. This series of off-site, research-based commissions aims to bring people together to develop ideas and partnerships, and has included discussions, screenings, and walks. Each encounter and public outcome provides opportunities for artists and audiences to engage with our locality. Our current Constellations projects illustrate how this strand of programming offers long-term, thoughtful connections and diverse ways to address mutual concerns, which may also be described as care.

One of these projects includes a commission by Petra Bauer, an artist and filmmaker based in Sweden who explores film as a space where political negotiations take place.13 She has been commissioned and supported by Collective to undertake a project in collaboration with SCOT-PEP,14 a charity based in Edinburgh dedicated to the promotion of sex workers’ rights. For over three years, Petra has worked with SCOT-PEP, leading a series of closed workshops exploring filmmaking strategies and the daily challenges and struggles of this sex worker led organization. Through an ongoing process of listening, sharing knowledge about labor rights and film production, the group asks: “How do you act politically when stigma prevents you from being public?”

These discussions have generated a film script with performance and gesture at its heart. This ongoing project developed with close support from Collective’s producer Frances Stacey will be shown at Collective in 2018. We aim through this project to create stronger ties and solidarity and create useful tools for SCOT-PEP and those who now form a constituency for the organization. The act of care in listening and developing mutualities has also encouraged all involved to think through what visibility and invisibility offers, as we negotiate the specific needs of the group and the specific risk implicit for them.

Artists’ projects have enabled Collective to engage with the complexity of our panorama, both the ground that we are working in (our locality) and the horizon we are striving to meet (the possibility of addressing shared concerns) or to imagine different panoramas through their eyes. Through the practice of working with artists, engaging in both tacit and explicit forms of unlearning, we come together to think through making and to discover many forms of speech and visibility. We open up ways to consider how art can act as a lens to bring things into focus that are hard to locate or make visible. By making room for a generative process of production rather than presentation alone, our expectations necessarily need to remain flexible. This can create challenges for an organization, but ones that have proved useful for discussing the aims and intentions of artists, citizens or constituencies. The challenge of meaningful collaboration in this context and speaking through art is at the heart of Collective’s commitment to the possibility of mutual confidence.

Towards a New Kind of City Observatory

Robert Barker’s concept of the panorama was specific to visual representation. We now find ourselves perched on a hill, trying to unlearn many things with which the site has become entangled since his coining of a phrase. These include pseudo-natural notions of sight, speech and culture and who can be seen, who will be heard and who can produce culture. We aim to begin to both complicate simplistic received histories and unpick complex narratives in order to make them visible to audiences.

Considering always how Collective might care through our repurposing of Edinburgh’s City Observatory, we ask, how will it perform this role? How can it be engaged with? How does it articulate its complex nature through the connecting of a multitude of voices? And what might it mean to our contemporary socio-political landscape? An Exchange of Method gave us valuable tools to reflect, discuss, broaden our panorama and acknowledge the connections between different actors within that specific panorama, both contemporary and historical. In this new kind of City Observatory, how will Collective support artists and others to stretch and weave between actors in the landscape, whether people, architecture or objects? And what can be produced between artists and other people within this global panorama?

Small Arts Organizations and Common Practice

The notion of care and its relationship to art organizations is emerging as a shared concern with many organizations in the UK. Common Practice,15 founded in 2009, is an advocacy group working for the recognition of the small-scale contemporary visual arts sector in London. This group is an example of the focus on care and collaboration that develops thought and practice in the understanding of care. Common Practice aims to promote the value of the sector and its activities, act as a knowledge base and resource for members and affiliated organizations, and develop a dialogue with other visual art organizations on a local, national and international level. The group’s founding members were Afterall, Chisenhale Gallery, Electra, Gasworks, LUX, Matt’s Gallery, Mute, The Showroom and Studio Voltaire. Collective is one of the affiliated organizations outside of London.

Together, the project represents a diverse range of activities including commissioning, production, publishing, research, exhibitions, residencies and artists’ studios. Common Practice has commissioned research papers including Practicing Solidarity, written by London-based artist and researcher Carla Cruz, which An Exchange of Method relates to. This paper built on the conference Public Assets, which Common Practice organized with Andrea Phillips in February 2015.16 It expands on notions of meritocracy and solidarity that have been examined by Phillips and members of Common Practice, including Collective, in public discussions. The paper reviews the increasingly competitive nature of the arts sector and questions the consequences of ‘opting out’ of this competition in favor of more mutuality. Finally, it highlights the emergence of cooperation and solidarity as strategies to overcome the competitiveness, individualization and the precarity of those who work in the arts, as well as how this might develop in the wider economy.

As part of the conference “Public Assets,” Kodwo Eshun, an artist from The Otolith Group,17 spoke about the possibilities and capacities of small-scale visual art organizations to foster care as a value. This is as opposed to large-scale organizations who may not have the capacity (or habits) to do so, possibly because they lack the ability or flexibility to unlearn. Kodwo believes care is performed and that perhaps the platforms on which care can take place are important to reflect on. Platforms, he reminds us, are structures on which performances of care can take place. Small organizations, such as Collective, Artlink, and all the Brazilian organizations involved in An Exchange of Method, and those involved in Common Practice London, may be the very structures needed. These small-scale organizations connect artists and actors within communities and localities and reproduce care through performance and gesture, creating important testing grounds.

Kodwo Eshun from The Otolith Group at Public Assets, a conference organized by Common Practice, London, 2015. Video via AQNB Productions.

Kodwo mused during his address to Public Assets that the etymology of the word curator, as coming from Latin agent noun curatus, as in “to take care of”, originally pertained to those put in charge of minors, those with mental illness, etc. This word has transitioned to one who cares for objects in museums, and more recently, one who is the conceiver, overseer and guardian of an exhibition or program. Small visual art organizations may have metabolized this idea (that of taking care) until it has become an attitude of caring and living production with artists and others drawn to the vision, project or method. A community of and for the work. Ideas as well as people need nurturing or caring for by the structure or organization who has the ability to take responsible risk. The capacity to nurture, the adventure of a process, with and for others, and supporting the production of work is at the heart of both Collective’s Satellites and Constellations programs.

This willingness to be a platform for living production is reflected in An Exchange of Method and all the artists and organizations involved in both Scotland and Brazil. At Collective, through experienced and thoughtful producers, we believe we have the care needed to connect and facilitate a broad range of conversations which may open out from, but not be directly related to, exhibitions or public outcomes. The value of the projects we engage with rests mostly in the “backstage” of the project, that which is instrumental to production, but is not presented to a public. In this way, the organization is a platform for both practice and production and “making public.”18 In developing practices, holding durational conversation and making public, care is central.

Through projects like Common Practice and An Exchange of Method we see that small organizations do nurture and make public with and for artists, groups, and constituencies. They can hold spaces in which to listen to each other or listen together. To learn and unlearn; to recognize care at work through projects; and to reflect on the roles we perform and ourselves. These processes enable us to focus on nurturing ideas that bring people together and provide a platform for shared concerns. Through the Brazilian-Scottish exchanges of this project, the reflection it has offered and the ‘thickening’ of thought that many minds and practices bring to the topic of care, we have learnt much and we continue to evolve.

Collective will work on the possibility of a new kind of City Observatory, a collective challenge, a mechanism for bringing different things into focus, making the invisible visible. We are proud to collaborate with so many dynamic, considerate and thorough artists and organizations that help us to reflect on our role and develop through unlearning. The production of different types of knowledge is incremental but crucial to our shared futures. By supporting the potential of art to make significant contributions to our complex times, we are all caring for the future.

Social Reproduction: Care as Method

There are many complex challenges in setting out to unlearn within the City Observatory. The sharing and consciousness-raising of particular theories and methods forms part of this, as Collective often host groups which have shared concerns or paths of enquiry. A group we are currently hosting is the Social Reproduction Reading Group, which was founded by Kirsten Lloyd and Victoria Horne in 2014.19 This group has always functioned semi-autonomously from any institution, although the founders have connections to academia. It is very much driven by the members and responds to their collective research interests. We are lucky to have a text by Kirsten within this publication that connects An Exchange of Method with her own research into social reproduction.20

In hosting this feminist reading group, Collective articulates an interest in methods of sharing and mutuality. The concept of social reproduction often underpins the discussions we have around hidden labor and habits implicit in our organizational practices. Much of how we aim to engage in and reflect on art production and how it takes place centers on our belief that art practice can be a tool to begin to loosen, and perhaps even unravel, the habits which are unconscious in the way we operate. These structures and habits transmit inequality from one generation to the next. Therefore unraveling and re-thinking them can be instrumental to wider shifts. Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu identified four types of capital that contribute to social reproduction in society: They are financial capital, cultural capital, human capital, and social capital. These types are intertwined and affect the various forms of capital that an art organization is routinely involved with. So, we look to recent discussions to find a useful way to utilize these ideas.

The Social Reproduction Reading Group define their interest in social reproduction as having emerged as a term in feminist thinking to describe the reproduction of daily life and the labor force under capitalism. This complex work, exceeding but incorporating child-rearing and domestic labor, has historically been excluded from analyses of the ‘real’ or monetary economy and from the wage relation. The notion of social reproduction connects to both education and health in a multitude of ways, which I believe have a fundamental connection to notions of care. This is because these activities and habits, which are excluded from the monetary economy, are a crucial signpost to care. We have been reflecting on social reproduction as a way to expand our understanding of what social reproduction might mean to artists and an art organization. Furthermore, we ask how it is negotiated in the broader art field, understanding that it is transversal and connects with many other areas of study.

The reading group read texts chosen by its members. They began with Silvia Federici’s “Wages Against Housework” (1975). Narratives that are often hidden or excluded, such as those addressed through social reproduction, provide a lens through which we might understand the complex relationships between care and production. This is evident in the project Collective commissioned between Petra Bauer and SCOT-PEP as well, which points to questions of social reproduction and autonomy in institutional frameworks. This form of reproduction can make visible specific personal and institutional habits, creating one strategy that allows us to reflect on how an art organization might attempt to generate the cracks of possibilities towards a feminist decolonial practice. Collective understands that its challenge is to extend these cracks and offer transversal connections within them, while acknowledging the fierce economic regime we operate in.

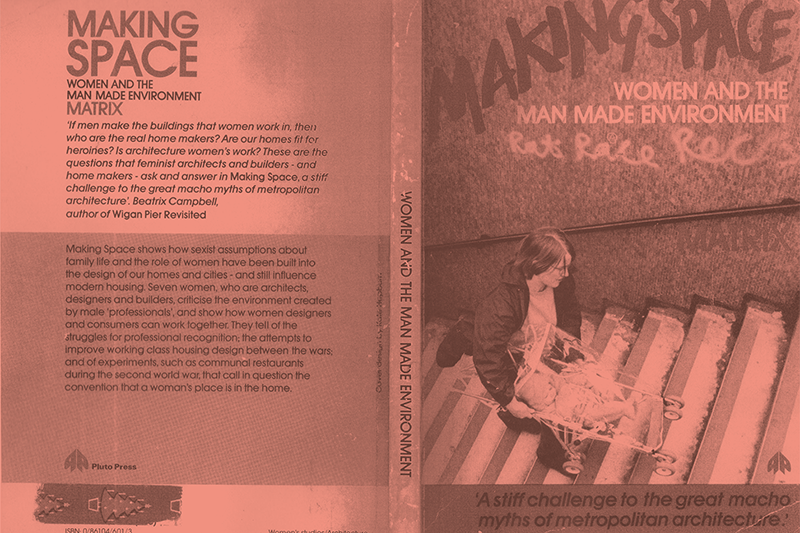

I mentioned earlier in this text the essay, “A Contemporary Observatory for the City,”. In his reflections the writer and curator Simon Sheikh raises a key question for Collective as a new kind of City Observatory: “If the institution is, then, a machine that produces specific subjects, what can be asked of transforming, not the factory into a gallery, nor the gallery into a space of immaterial labor, but the historical observatory into a contemporary gallery?” And as the artist Hito Steyerl has remarked in her essay “Is a Museum a Factory?” the museum generally does not make labor visible, but rather conceals the actual labor of installation, cleaning etc., but is nonetheless “…a space for production” and “a space for exploitation.”

This is a complex panorama with many collaborators and Collective acknowledges all the artists, groups, constituencies, and staff members that have collaborated on our ever-evolving organizational method and continue to do so. The influence of artists and others is palpable in our work and as an organization we are often holding a space, a platform for others to act upon. We need to take care not to seemingly colonize the knowledge or ideas of those we collaborate with within the process of decolonization. In this text, I have argued that perhaps, although it is a complex process, small-scale organizations are best placed to merge ‘backstage’ and ‘on stage’ and through working together, with care as method we can institute new forms of platform which also serve our constituencies better.

***

Kate Gray

Kate Gray has been Director of Collective, Edinburgh since 2009, where previously she led Collective’s One Mile Programme (2006-2009). Collective brings people together around the production of new work and Kate’s program at Collective has a focused on co-production between artists and people who would not describe themselves as artists. Recent commissions have included Dineo Seshee Bopape, Hito Steyerl, Goldin and Senneby, Jesse Jones, Slavs and Tatars, Simon Martin, Grace Schwindt and Petra Bauer. Kate has led the relocation of Collective by repurposing the City Observatory on Edinburgh’s iconic Calton Hill to be a new centre for contemporary art in 2018. She studied at Oxford and Sheffield Hallam Universities before completing an MFA at Glasgow School of Art. She was the first Chair of Rhubaba, artist-run gallery and studios (2014-2017) and is a visiting lecturer at Glasgow School of Art and Edinburgh College of Art.

_______

1 ‘On stage’ and ‘backstage’ is a concept that is discussed within the Satellites Program, specifically introduced by artist James N Hutchinson who has been the group facilitator of Satellites since 2015. He refers specifically to the text “Backstage and Processuality: Unfolding the installation sites of Curatorial Projects” by Ines Moreira published in The Curatorial – A Philosophy of Curating edited by Jean Paul Martinon, (London: Bloomsbury, 2013) in which she says, “A backstage refers, as well, to a state of incompletion, an unfinished place where ‘the making’ takes place. A backstage generates exhibitions, extends artist’s studios and creates exhibitionary structures, from spatial installations to scenographies.” 225-234.

2 Towards a City Observatory: Constellations in Art, Collaboration and Locality is a publication produced by Collective in 2017. Reflecting on the long journey undertaken to reach this point, Towards a City Observatory, invites artists, writers and thinkers to imagine a new kind of observatory, which brings people together through contemporary art. The publication represents a moment of pause for Collective on the threshold of change and considers some of its pivotal projects from the past five years to inform the future. Towards a City Observatory features contributions from Charles Esche, Lesley Young, Simon Sheikh, Emma Hedditch, Wendelien van Oldenborgh, Sharam Khosravi and many more of the peers who have helped to make Collective a plural entity since it was formed in 1984. The book is designed by Åbäke with a limited edition of two hundred including a unique bi-colour edge. A free pdf can be accessed here and a print on demand version can be purchased here.

3 It is not my project here to analyze all the complexities of thinking about decolonization in an exchange project with Brazil, as this would precipitate another text. However, some things must be acknowledged, including the complex nature of funding from the British Council and the traps of defining an organization, the individual and the nuanced relationships between them with an evolving understanding of a different context. This has been discussed many times within Collective during the course of the project and also in the editing process of this publication.

4 Norte Comum became involved, in 2014, with Hotel da Loucura (Madness Hotel), a project that emerged under the auspices of Universidade Popular da Ciência e Arte (Popular University of Art and Science) in collaboration with a division of the Rio de Janeiro municipal department of health and the Instituto Municipal Nise da Silveira, a psychiatric hospital in the Rio suburb of Engenho de Dentro named after the famous psychiatrist. The collective occupied an abandoned hospital ward opening up a wide range of activities for mental health users and patients and they began a program of activities to highlight humanitarian issues and creative expression. See video interviews with Jefferson Vasoncellos and Pablo Meijueiro in Part 1 of the video Care as Method in this magazine [http://institutomesa.org/revistamesa/edicoes/5/portfolio/cuidado-como-metodo-en/?lang=en]

5 The project at Centro Municipal de Arte Hélio Oiticica was connected to Izabela’s research and curation. Their residency was part of a curatorial initiative related to the exhibition Bandeiras na Praça (Flags on the Square) recovering the history of the art happening/protest in 1967 in Rio de Janeiro together with contemporary protest and public intervention initiatives.

6 Presented as an evaluation, Somersault is an exploration of the experience of taking part in All Sided Games (2013—15) by Julie Crawshaw, commissioned by Collective. Somersault supports the understanding of what All Sided Games meant to participants and experiments with how evaluations might better capture the complexity of the relational associations of participating in an artwork. All Sided Games set out to find new ways to work with families in their locality, seeking out areas of mutual interest by thinking and acting through the production and presentation of art. Six artist commissions by Jacob Dahlgren, Mitch Miller, Cristina Lucas, Nils Norman & Assemble, Florrie James and Dennis McNulty brought artists, individuals and groups together in and around venues built or used for the Edinburgh 1970 and 1986 Commonwealth Games and the Glasgow 2014 Games. The project also explored and expanded on ideas of the local through How Near is Here? a symposium and intensive program. The book can be accessed here.

7 Institutional critique is the act of critiquing an institution as artistic practice. In the 1960s the art institution was often perceived as a place of “cultural confinement” and thus something to attack aesthetically, politically and theoretically. There are many exponents of institutional critique including Hans Haacke. From the 1980s onwards, critical discussions have been held by curators, producers and directors within art organizations addressing this very subject, fostering what has been termed in Europe and the UK as new institutionalism. Here the institution is not only the problem but also the potential solution. It is possible to imagine that Collective, being formed by artists in 1984, when they were very aware of institutional critique, the act of instituting the organization as artists may have also been a form of institutional critique. Therefore, I feel keeping artists’ practice as the driving force of Collective is necessary to ensure the organization does not become a place of “cultural confinement.”

8 Shona Macnaughton was a co-director of Embassy Gallery. Since then, she has pursued her own art practice that has been made public via exhibitions, performances, talks and essays. Alongside this she takes part in projects with the collective Eastern Surf. Her practice is rooted in performance, writing and film, and questions of technology, subjectivity and labor, staging re-enactments of the relationships between characters, making scripts and actions that are set up to confront an audience. She uses a method of reframing texts relating to the site of display, transferring them from their original context onto present political and technological conditions. Her work is responsive to the political climate around specific architectures, which can be both physical and virtual spaces and how their design works. Her website can be accessed here.

9 Annette Krauss, Sites for Unlearning: On the Material, Artistic and Political Dimensions of Processes of Unlearning (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2019) Forthcoming.

10 Annette Krauss has a conceptually-based practice in which she addresses the intersection of art, politics and everyday life. Her work revolves around informal knowledge and normalization processes that shape our bodies, the way we use objects, engage in social practices and how these influence the way we know and act in the world. Her artistic work emerges through the intersection of different media, such as performance, video, historical and everyday research, pedagogy and texts. Krauss has co-initiated various long-term collaborative practices (The Hidden Curriculum; Sites for Unlearning; Read-in; ASK!; Read the Masks. Tradition is Not Given; and School of Temporalities.) These projects reflect and build upon the potential of collaboration, while aiming at disrupting taken for granted ‘truths’ in theory and practice. Her project websites can be accessed here, here and here.

11 R. D. Laing was born in Glasgow. He never denied the existence of mental illness, but viewed it in a radically different light from his contemporaries. For Laing, mental illness could be a transformative episode whereby the process of undergoing mental distress was compared to a shamanic journey. The traveller could return from the journey with important insights and may have become a wiser and more grounded person as a result. In his first and best-known book, The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness (1960), he contrasted the experience of the “ontologically secure” person with that of a person who “cannot take the realness, aliveness, autonomy and identity of himself and others for granted” and who consequently contrives strategies to avoid “losing his self”. Laing argued that the old Bedlam-based system of incarcerating people with mental illnesses and treating them with anti-psychotic drugs and electric-shock treatment had contributed to people’s psychological and emotional distress. With his beliefs in the power of self-healing, he became an important part of the anti-asylum movement, which worked towards the community-care model that is the norm in the UK today. However, this process was first advocated in 1962 by the then Conservative health minister Enoch Powell for mainly economic reasons, and therefore its legacy is often considered tainted.

12Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) proposes a pedagogy with a new relationship between teacher, student, and society. Based on his own experience helping Brazilian adults to read and write, Freire includes a detailed Marxist class analysis in his exploration of the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized. In the book, Freire calls traditional pedagogy the “banking model of education” because it treats the student as an empty vessel to be filled with knowledge. However, he argues for pedagogy to treat the learner as a co-creator of knowledge.

13 Petra Bauer works to ask how we can think of film as political action. Bridging the gaps between aesthetics and politics, artist and filmmaker, she reflects on her own experience in making political films and launches a theoretical argument in Sisters! Making Films, Doing Politics that – via Hannah Arendt’s ideas about the constitution of the political arena – uncovers the aesthetic mechanisms that underlie contemporary strategies for collective and feminist filmmaking. Her PhD project, Sisters! Making Films, Doing Politics draws on an extensive historical archive of radical filmmaking and film theory, with particular focus on the British film collectives of the 1970s and films made by Palestinian and Israeli filmmakers. At the centre of the investigation stands Sisters!, Petra’s collaborative film project with the London-based feminist organization Southall Black Sisters. Petra’s dissertation can be download here. Her collaborative projects in the UK can be seen here and here.

14 SCOT-PEP are a sex worker-led charity that advocates for the safety, rights and health of everyone who sells sex in Scotland. They believe that sex work is work, and that sex workers deserve protections such as labor rights. Along with Amnesty International, the World Health Organization and the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women, they believe that the decriminalization of sex work best upholds the safety and rights of people who sell sex. They aim to organize and unionize for better workplace conditions, to make the voices of sex workers heard and to challenge punitive policies which attempt to limit migration, increasing the vulnerability of migrants who sell sex to exploitation and abuse. They view exploitation as best tackled by strengthening and upholding the rights of migrants who sell sex, especially undocumented migrants. Their website with many resources can be accessed here.

15Research papers from Common Practice, London can be accessed here. There are also Common Practice branches in New York and Los Angeles. The founding members of Common Practice New York are Artists Space, The Kitchen, Light Industry, Participant Inc., Printed Matter, Triple Canopy, and White Columns. Their website can be accessed here. The founding members of Common Practice Los Angeles are East of Borneo, Human Resources, LACE, LA><ART, the MAK Center, REDCAT, and X-TRA / Project X. Their website can be accessed here.

16 Building on previous work on value and sustainability in the UK’s small-scale arts sector, Common Practice organized a one-day conference to discuss the ways in which arts organizations produce artistic value beyond measurability and quantification, provide spaces for public experience extra to the market, and in so doing contribute importantly to cultural wealth. In this way, small-scale arts organizations provide ample evidence of the necessity to build rather than diminish state funding for the arts as a core public asset. The conference took place on 15th February 2015 at the Platform Theatre, Central Saint Martins. Speakers included: Jesús Carrillo, Kodwo Eshun, Charlotte Higgins, Maria Lind, Andrea Phillips and Lise Soskolne (W.A.G.E.). All contributions can be watched here.

17 The Otolith Group is an award-winning artist led collective and organization founded by Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun in 2002. Their practice integrates film and video making, artists writing, workshops, exhibition curation, publication and developing public platforms for the close readings of the image in contemporary society. The Otolith Collective coexists by curating, programming, publishing and supporting the presentation of artists’ work, contributing to a critical field of exploration between visual culture and exhibiting in contemporary art. Their website can be accessed here.

18 Making public’ is a phrase often used by those who advocate for an expanded notion of curating that goes beyond exhibitions, with other ways of making art happen and go public. Many artists, curators, producers and directors have simultaneously embraced other ways of producing art and allowing it to exist in a way that makes the most sense in relation to the kind of art, the time, and the place. Maria Lind says “the term ‘curating’ is used as the technical modality of making art go public.” Maria Lind, “Performing the Curatorial: An Introduction” in Performing the Curatorial: Within and Beyond Art ed Maria Lind (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), 11. Other theorists have also taken forward these ideas.

19 In the fields of anthropology, sociology, religious studies, human-centred design and organizational development, a ‘thick’ description of a human behavior is one that explains not just the behavior, but its context as well, such that the behavior becomes meaningful to an outsider. The term was introduced by the 20th century philosopher Gilbert Ryle (1900-1976). Anthropologist Clifford Geertz later developed the concept in his book The Interpretation of Cultures (1973).

20 Kirsten Lloyd. “Caring in Public: notes on the Mediation of Social Practice” [http://institutomesa.org/revistamesa/edicoes/5/kristen-lloyd-en/?lang=en]