Installation view of the exhibition Rubens Gerchman: With the Resignation Letter in My Pocket, August 8th, 2014 – February 8th, 2015, Casa Daros. Photo: Felipe Moreno

Parque Lage, Rio de Janeiro, 1975-1979: An Experimental Art School and Its Contemporary Resonance

A conversation with Clara Gerchman (director of Rubens Gerchman Institute),

Bia Coelho (artist), Bia Jabor (art and education manager at Casa Daros)

and João de Albuquerque (artist educator at Casa Daros)

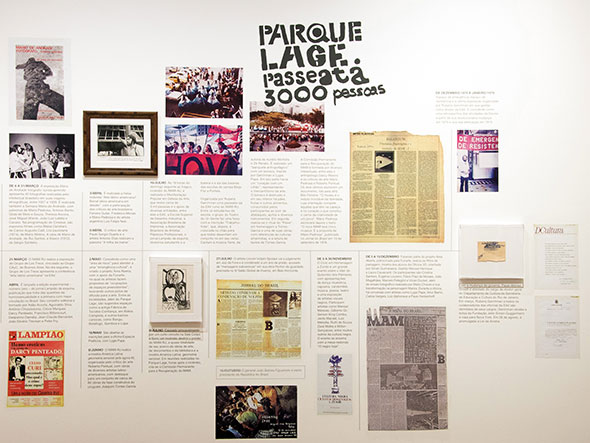

In 2014, Casa Daros and the Rubens Gerchman Institute presented the exhibition Rubens Gerchman: With the Resignation Letter in My Pocket exploring the innovative history of the School of Visual Arts of Parque Lage during the time the artist was the director of the institution (1975-1979). Gerchman (1942-2008), who worked in various media and was part of the Brazilian art vanguard of the 1960s, “gathered talented teachers and collaborators who were interested in de-academizing the school and transforming it into a laboratory.” 1

Eugenio Valdés Figueroa (former director of art and education at Casa Daros) and Clara Gerchman (Rubens Gerchman’s daughter and the director of Rubens Gerchman Institute2) co-curated the exhibition, which featured a timeline from 1966 to 1979 including happenings at the school and references to the counterculture of the time illustrated with photographs, posters and publications that belonged to the Institute Rubens Gerchman. The exhibition also presented a rich series of video interviews with various artists and colleagues of Gerchman.

The exhibition title came from a conversation between Gerchman and the architect Lina Bo Bardi (1914-1992) in 1975 when the artist was unsure of accepting the invitation to direct the former Instituto de Belas Artes do Rio de Janeiro (Fine Arts Institute). Bo Bardi said, “Accept it! And if you think you should leave, just resign.” Then, as Figueroa recounts, together Gerchman and Lina wrote his resignation letter. Gerchman, who was ready to hand in the letter at any time, carried it already signed in his pocket for many years: “it was not a gesture of disengagement, but of autonomy, of freedom of choice.” 3

As part of the exhibition, Casa Daros developed various projects inspired by this experimental legacy. One of these projects was a special course for young artists, called Contemporary Laboratory: Proposals and Discoveries of What Art Is (or Could Be) conceived and coordinated by Instituto MESA and Coletivo E.

On the afternoon of April 1st, a small group of those involved in these initiatives got together to talk about this experimental history and its contemporary relevance: Clara Gerchman, Rubens Gerchman’s daughter and the director of the Institute Rubens Gerchman; Bia Jabor, art and education manager at Casa Daros; João de Albuquerque, artist educator at Casa Daros; Jessica Gogan, director of Instituto MESA and Beatriz Coelho, “non-artist” and Contemporary Laboratory participant.

Jessica: I was on my way here, rereading some things and I read this beautiful sentence by the filmmaker Sergio Santeiro: “Just like samba, cinema can’t be learnt at school.”4 So I asked myself, “why a school?” And, mainly, what the notion of school meant to Rubens Gerchman? Why create one? Why was that interesting? If art is like samba and can’t be learnt at school, what can we learn there?

Clara: I think it was about conviviality, mixing different skills and forms of knowledge and what results from that experience. To a point where my father [Gerchman] didn’t use to refer to the teachers as teachers. He talked about them as a kind of guide or mentor. There wasn’t this figure who would really teach you something, but rather someone to orient your choices, provoke experiences. And Gerchman didn’t refer to the students as students, but as users of the space, of this conviviality, this encounter. So I think that’s what it was: a space to experience, to be together. It was about the collective. I don’t see it as a traditional school, from the perspective of teaching, no. He always spoke about this conviviality as a kind of broad “communicant network”5 between people and various areas of knowledge. Instead of emphasizing techniques, he used concepts such as the home, the body, the cosmos, and the everyday. These would all interconnect in a transdisciplinary manner, creating a great laboratory space.

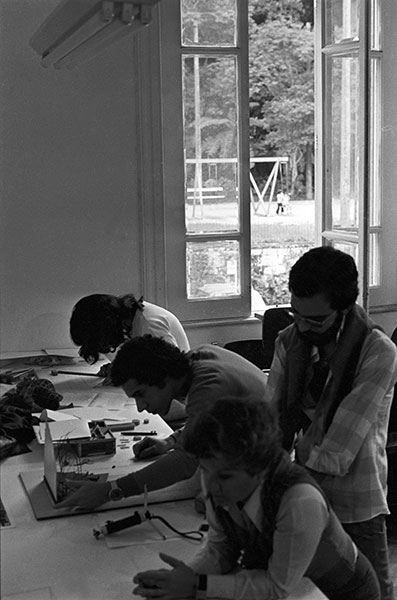

Mounting of the World Photography exhibition at Parque Lage – School of Visual Arts. Rubens Gerchman Institute and Helio Eichbauer archive.

Bia Jabor: I believe that there was this concern to reinvent the space of the school and to mix up and change these “traditional” nomenclatures. It was almost like reinventing these characters within the very idea of a school. This strategy is very interesting. The teacher isn’t a teacher, the student isn’t a student and the school isn’t exactly a school. Gerchman reinvented all these characters and places to try to get to another place.

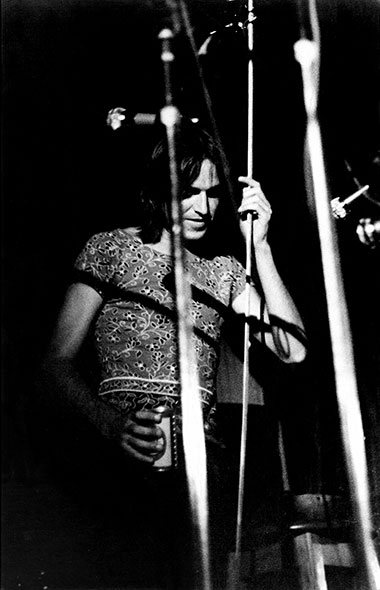

Performance during the everyday workshop facilitated by Rubens Gerchman. Rubens Gerchman Institute and Helio Eichbauer archive.

Clara: I am thinking here about what Santeiro said: that the school is not the place where you learn about moviemaking. I think as well it has a bit to do with the Cinema Novo. Camera in hand and an idea in mind. Also, if we look back historically… it was the 70s. Experimentation. It was the time of the Super 8.

Bia Jabor: Yes, Santeiro led the Cineave [Cinema Project at Parque Lage]. While he said – and I think this also has to do with Gerchman’s proposal – that it’s not possible to learn filmmaking in school, it was however possible to live cinema in school.

Clara: Yes, to be there full time.

Bia Jabor: Yes. Reflecting on your practice, making posters, picking up the camera and just filming, watching movies together, debating, criticizing; it wasn’t about teaching how to make movies, but making them. This could be lived at school. Nobody teaches you how to make movies, as nobody teaches you how to make art, to be an artist.

João: Is it possible to educate artists? So what is an art school for?

Bia Jabor: Maybe it’s more a kind of space where you can have these experiences and share them.

João: I think it’s more like an idea of training or rather “forming” as a process of experimentation, a kind of individualized learning. As Gerchman said at the time the school was founded: “The school project will be reformulated each semester, absorbing the experience obtained by the students and teachers, embodying the development of each person’s experimentations. The viability of the art school lies in its capacity of considering each student an individual thinker, […] a proposer, a discoverer of what art is.”6 The school reinvents itself, it’s made by the students, it understands that the student has an individual process; he is a proposer; he learns by experimenting. And the school needs to reformulate itself according to the student. It’s imperative to not invade this experimentation space. The great master is the one who doesn’t get in the way.

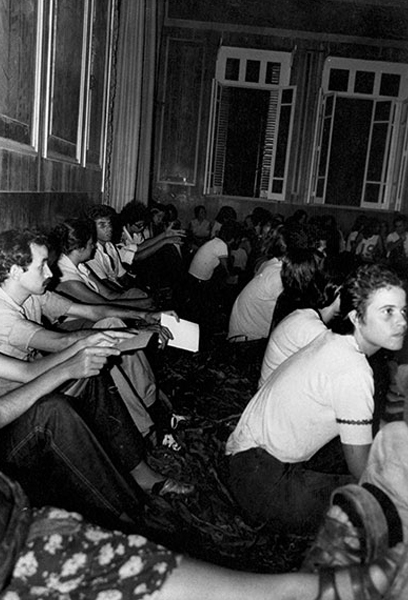

Set design workshop facilitated by Marcos Flaksman. Rubens Gerchman Institute and Helio Eichbauer archive.

Bia Jabor: Something I find very interesting is the fact that Gerchman, as an artist and not as an educator, had this vision: to rethink the teaching of art. If you take this out of the context of the visual arts and think about what is being discussed today regarding education and the desire to rework traditional school models, there are a lot of parallels with what Gerchman did at the School of Visual Arts back then: to break the walls that separate disciplines, create a horizontal interaction between teacher and student, and propose a transdisciplinary curriculum. The educator José Pacheco and his Escola da Ponte (Bridge School) is all about this.7 What he proposes in terms of education and a community of learning is exactly this. There isn’t this role of a teacher but rather a tutor, someone who orients you. Learning comes from the student, from his or her desire to learn and curiosity for exploring the world. But it is very interesting when this proposal comes from an artist. Gerchman didn’t have any training in the field of pedagogy.

Clara: It was all by absorption. He lived, he read, he reflected, he saw, he experienced and then he brought it all to the School.

Jessica: But where did the interest in education come from? Why do you think he was interested in this project? He was the one to change the name from Instituto de Belas Artes (Fine Arts Institute) to School of Visual Arts of Parque Lage…

Clara: It think it comes from the School of Visual Arts model. It’s that simple. Gerchman arrived from the United States where he had experiences with filmmaking and with all that was going on in the art world, that American cauldron of the 60s and the 70s. And because of that I think the name School of Visual Arts seemed right. I don’t think there is any poetry in the name. I think that the names of the courses were very poetic, deliberately. For example, oficinas do corpo e pluridimensional (body and pluridimensional workshops), offered by the set designer Helio Eichbauer8 that eventually became the idea of “spectacle conference” – a hybrid of performances and body exercises, dances, readings, theatre… Or the oficina do vestuário (T.N vestuário in Portuguese can mean vestment, ensemble, costume, etc.), offered by Rosa Magalhães9… espaço poético (poetic space) given by the artist Lygia Pape10 and the name oficina das artes do fogo (fire arts workshop) instead of ceramics. I think that’s beautiful.

Pluridimensional workshop facilitated by Helio Eichbauer c.1975. Rubens Gerchman Institute and Helio Eichbauer archive.

Bia Jabor: The school wasn’t focused on particular techniques.

João: Art not as an endpoint, rather as process.

Jessica: This situation… art as process, considering each student as a proposer… that’s what we tried to do in the Contemporary Laboratory: Proposals and Discoveries of What Art is (or Could Be). We added “or could be” as a means of considering new possibilities. For you, Bia [Coelho], as one of the young artists who participated in the Laboratory, how do you see Gerchman’s way of thinking in those laboratories?

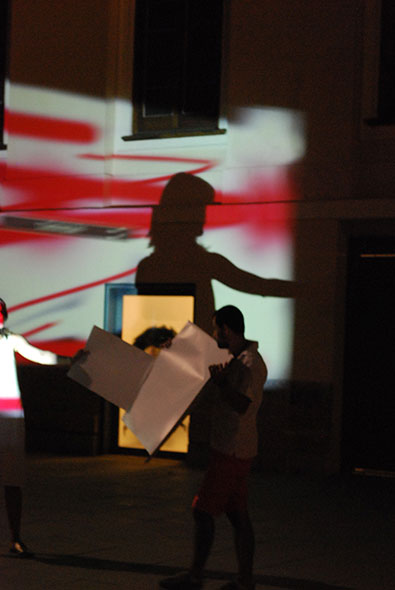

Contemporary Laboratory. Experiments on the internal patio of Casa Daros, October 31st, 2014. Photo: Jessica Gogan

Bia Coelho: I feel it’s exactly what’s been said. We didn’t have any teachers here in the Laboratory. We had the presence of people from the art scene who came to talk to us openly. And that’s the same experience I have had at Parque Lage. I have few teachers, in the sense of sitting in a chair and listening to the teacher talking. In most classes, I have had teachers who don’t have any academic training in education. I guess the same happened when Gerchman and Hélio [Eichbauer] were teachers. Although they had particular kinds of training and programs of study. Hélio went to Prague, to a more formal design school. But they are artists, essentially. In the classes I’ve had so far we just get there and do things. Sometimes it’s even hard.

Clara: Do you think it’s free?

Bia Coelho: I think it’s free. Not completely, as nothing is. But that’s what I felt during the Laboratory. They told us to do something, to go to the patio and do a performance… And I had never done a performance. I’m not into theatre. I like to watch it but body-related things are hard for me. I’m more into visual arts. So I was always being tested, all the time: “Let’s go and make something.” And I found that fantastic. At the time, I got butterflies in my stomach and thought, “Nothing is going to come out of this…” but in the end, there was always something good. And I think that it’s because of this, the influences you get freely from what’s around you, without being put in a mode of production. You just go there and do whatever you want. And I think the same happened back then (70s). Ok, it’s true that Parque Lage is very different now, but there is still there the same thing I had in the Laboratory: total freedom, and the push, all of the time, to produce something. That was great, very positive.

Jessica: One thing from that time that remains very important is the idea of multiple languages. Bia [Coelho] comes from photography, but in the Laboratory there were also people from performance, dance, fashion etc. The languages were very different. I think this idea of breaking the isolation between disciplines was always present for Gerchman. Why do you think that was important? And did he manage to do that?

Clara: For Hélio Eichbauer’s ‘pluridimensional’ classes… they went there all dressed up, in costumes. That’s wonderful… to break traditions, to experience, to read together and be there. They were characters… He encouraged the students’ involvement to develop research directions, the construction of the characters, the drawing and the construction of models, studies of symbols in various traditions, including engaging in ritual behavior, collective hose baths, and many other manifestations in which body awareness was applied and integrated within an artistic process. It was mad! Also, the themes of the spectacle conferences portrayed that mixture and the breaking down of barriers between worlds and practices. They were very diverse thematically, such as “Isadora Duncan – Brasil 1916 – Dança e Educação” (Isadora Duncan – Brazil 1916 – Dance and Education) or “O círculo, o quadrado e o triângulo” (The Circle, the Square and the Triangle) or “Lendas indígenas, afro-brasileiras e suas concepções cosmogônicas” (Indigenous Legends, Afro-Brazilians and their Cosmological Conceptions)… imagine all that!

Pluridimensional workshop facilitated by Helio Eichbauer. Rubens Gerchman Institute and Helio Eichbauer archive.

Bia Jabor: Comparing Parque Lage at the time and now, looking back there was a great field of experimentation. Perhaps, such a free experimentation space existed, of course it’s always very difficult to talk about freedom, curiously (or not) as all this happened during the military dictatorship…11

João: It was almost a contradictory isolation. You break the isolation by having to isolate yourself in a violent historical period. Parque Lage was isolated. From the front gate inwards, everything was free. It was an experimental space born inside that context. I remember the video interview where Gerchman says: “I spend the weekend separating the works, organizing them, so when the students arrive on Monday, there is always something different to be seen.”12 All this came about without bureaucracy. It was more like: “let’s make things happen.” Not that it was purely practiced based, of course it wasn’t, but “making” was valued more.

Bia Jabor: But at the same time, when you see the course outlines… maybe there wasn’t as much bureaucracy as you see nowadays in institutions, but there was a great discipline behind it all… Otherwise, it would have been chaos, imagine, it was already so free…

Clara: I think it was a commitment, you know?

João: Perhaps, there was an incentive. There are times when it seems that the whole world, a whole period conspires for something incredible to happen. I see that a lot at this school.

Clara: The characters there were wonderful. How was it possible to have so many good people together? I still don’t understand that. I find that amazing.

Jessica: I think this conviviality amongst people and also the question of isolation are very interesting. Because on one hand it’s necessary to break the isolation, but on the other it’s necessary to isolate oneself in order to protect the experimental space. But what was the contact between the school and the world outside? Was the school isolated?

Clara: From a cultural standpoint, no. Because it hosted a series of cultural manifestations, theatre groups, music groups, poetry and theatrical readings, poetry publications, shows, exhibitions, the first world photography exhibition… No, there was no cultural isolation at all, on the contrary. But I think they managed a political isolation.

World Photography exhibition at Parque Lage – School of the Visual Arts. Rubens Gerchman Institute and Helio Eichbauer archive.

João: Exactly. A spatial isolation that benefited the school.

Clara: We were talking to Ney Matogrosso.13 Because I’m keeping up with the research, you know… and now I’m talking to some of the people I didn’t get around to speaking to before. Ney Matogrosso was saying that he thought people were paying a lot of attention to what was going on in music. Music made a lot of noise, and so everyone engaged in it. Maybe cinema and music are easier to understand. And maybe poetry and other cultural manifestations were seen as secondary. And Parque Lage was the space they made for themselves. Heloisa Buarque de Hollanda herself said that nobody cared about poetry.14 She says poetry was the fifth category on the list… So, the School was a place for every kind of “underground” language and cultural experimentation at that time.

Verão a mil (Summer series of events) with the poet Xico Chaves. Rubens Gerchman Institute and Helio Eichbauer archive.

Bia Coelho: That thing you said about isolation is interesting. Non-physical isolation. Because at that time there was no isolation in terms of types of art, right? It seems to me that everybody was doing the same things; there was no such thing as, “I’m a visual artist,” “I’m a poet,” “I’m a performer”… it was a mix. The poet can do a performance or a painting… That happened to me at the Laboratory and in my first year at Parque Lage (2014). I started classes saying I was a photographer and got out of them without knowing what I am. At the end of the Laboratory, I did an installation. And that was wonderful. That was the best thing. I think that’s what the people felt at that time; that they were able to do anything.

Bia Jabor: Exactly. They were trying to experiment in every language and I think that sometime after that there was the need of separating these languages, maybe to define them. I, for example, studied arts at university in the 90s, and the subjects were very fragmented. You had installation, photography, printing… everything in its place. There was no intention of integrating or mixing media; there was nothing like that.

João: I’ve always given a lot of thought to what made the school what it was. The relation between art and market, production of art for sale… It didn’t work like that. I think that was essential so things could be real, honest.

Clara: That’s exactly what Jards Macalé15 and Heloisa Buarque de Hollanda said. The 80s changed everything, the market opened. In a part of the documentary [about Parque Lage at that time, made for the exhibition] Jards says this – and it’s even funny – “the hippies became yuppies and went to Wall Street.” Meaning that there was a real change. Let’s get into professionalization, into a market approach, into a market positioning.

Jessica: Charles Esche, curator of the last São Paulo Biennial, has an interesting article in which he talks about how to teach artists to “undo” the art world.16 He says that the most successful experimental art schools of the 20th century, even in very different parts of the world, have three characteristics in common: anti-hierarchy, anti-isolation and anti-specialization. So I think it’s fascinating that in our conversation over the last 20 minutes these elements are very present. From the perspective of Parque Lage, do you think there was any Brazilian aspect to this whole process? Not trying to be essentialist or tropicalist, but rather to think about a particular kind of positioning or dynamics that were present there? Amidst this anti-hierarchy, anti-isolation and anti-specialization was there a political dimension and how did this come into play or not?

Clara: I think that the atmosphere of Parque Lage, which is already in the middle of the forest, naturally has this “Brazilianness” and lack of bureaucracy… the rest, the methodologies they managed to put in place, were based on precepts of the Bauhaus or Black Mountain College. From the perspective more of commitment, of what they wanted to achieve… I think the space already enabled that. There was a spirit of solidarity. MAM (Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro) caught fire and everyone, including people from Parque Lage, went there.17 Hélio Oiticica, who had already entered MAM with Mangueira (samba school) in 1965, invited the carnival dancers to participate in the march against the fire at the carioca museum. I think this collective spirit is already so Brazilian… so present in our culture.

Installation view of the exhibition Rubens Gerchman: With the Resignation Letter in My Pocket, August 8th, 2014 – February 8th, 2015, Casa Daros. Photo: Alline Ourique.

Bia Jabor: But I think that the models always came from abroad. What were our models and references for a School of Arts? They didn’t exist… So maybe the references were always external examples, but when it comes to bringing them here, it becomes inevitably Brazilian, there’s no getting away from that. As much as Gerchman used models from the School of Visual Arts and was influenced by his experiences in New York, he couldn’t apply this model here. First, he was in the middle of the Atlantic rainforest at Parque Lage as well as amidst all the political, cultural, social, and local situations that affected a whole generation and artistic production. Hélio’s spirit when he took Mangueira to the museum also made it possible to bring the carnival dancers and the samba composers to the school.

João: I see a way of understanding this – there was a relationship of trust and autonomy at the school. Gerchman trusted people; they had total autonomy to plan their classes. He was more worried about getting everyone together and making things happen. Maybe the most Brazilian aspect in there was this sense of mixing. All these people were put together and it ended up as this amazing samba! Okay… this is also a big cliché: Brazilians mix everything and everything works and it’s good and cool… but I guess the blending of the relationship of trust and the autonomy happened via this hybridism.

Bia Jabor: And maybe even because of a certain institutional precariousness. Because this was also present, at times precariousness allows for improvisation. When you don’t have models and infrastructure, you improvise and sometimes very good things come out of this improvisation. Our foundations and structures are always very shaky; there is always a “missing piece,” so we improvise. In other countries where there are solid foundations and institutions, there are a lot of things you don’t have to worry about and because of this it is possible to create other spaces of freedom. For us, no. We are quick fixers, favelas, street vendors, samba, improvisation…

Jessica: This leads to another question… because it certainly is an element that was seen as important back then; this notion of creating an information archive, creating a collection of events, thought-processes. How might we facilitate a mode of thinking that will nurture this collection? What would an archive of Parque Lage be?

Clara: I think they are private archives. I guess we are talking about human archives… I’m inventing an expression here. Each person who participated would create and take their own “stuff” of what they learnt there. My father was an accumulator. He kept everything. Every move, break-up, relocation to another city, another neighborhood, another state… he would take everything, I don’t know how many photographs, notebooks… Hélio Eichbauer was someone who also kept a lot. And there was the fear, wasn’t there, of the dictatorship at the time? So people didn’t want to leave a lot of traces. I was talking to Claudia Saldanha, the former director of Parque Lage, and she said that there was an evasion. The directors went there, created, constituted, and took the school’s archive with them.

Bia Jabor: But I think it’s not only an issue of the moment of the dictatorship, that due to fear of losing institutional memory people kept documents themselves, like Gerchman did when he left Parque Lage. We also tend to forget history, right? This has to do with our formation as a nation ever since the Brazil of colonial times. This difficulty in recognizing and preserving our history is impressive. We have a serious memory problem.

Clara: Bia, how come the history of the school is so little known? It has been 40 years! There isn’t a book, just a catalogue, not a film documentary. We are just doing this now. Any school you go to has a bust of its founder. I’m not saying we should have a bust, but we should at least have a plate: “Established in 1975.” We showed the documentary we did at the School to the employees. The cleaner, the security guard… and they would say, “Oh really? So that’s what it is?” People have no sense of belonging. Look how serious that is…

João: Even the history of the house itself…

Clara: Exactly… You can’t do this you can’t do that. Why? What is this house? What is this park? It’s all protected… But who was Besanzoni? Why is there a bathtub?18 There should be a leaflet, a brochure.

Jessica: Yes… and we should also understand this history as a possibility. What was inspiring there? How can you weave a line of thinking with this history?

João: Some of the artists that interest me, like Luis Camnitzer and Antonio Caro, have a very interesting pedagogical disposition because they use art as a pedagogical tool. After I started studying different schools, teachers and methods, it became very clear to me that this “artistic-pedagogical” or “pedagogical-artistic” practice isn’t news, especially in the context of alternative pedagogy. You had Paulo Freire at that time. Thinking was tied to practice; it wasn’t detached. You are not the teacher who is teaching someone how to make ceramics. As a student you engaged with the artist’s personal research with what he or she was doing that was also outside the school. So it was rather: “Do it with me.” Actually, learning about this history was very inspiring to me. It was because of it that I encouraged myself to do my own work. I got the message: get out of it what you can and do your own thing.

Installation view of the exhibition Rubens Gerchman: With the Resignation Letter in My Pocket, August 8th, 2014 – February 8th, 2015, Casa Daros. Photo: Alline Ourique.

Bia Jabor: I think that from the artist educators’ team of Casa Daros, João was the one who better developed and took on this history because it tied in with his research as an artist. It was as if he had found an artistic thinking that nurtured him to carry on his research. João has always had a very experimental proposition based on listening… It will be good if you talk a bit about your project “O fazer existir” [Making Things Exist].

João: Back then, I was asking myself what people come to Casa Daros for. I would frequently ask: “What are you doing here? What interests you in here?” And I realized that people weren’t really aware of the reasons they came to a cultural center. So I started to do some research about it. I started to provide tools, space, time, an orientation, an encouragement, so people could do what they wanted to. That’s when Gerchman’s exhibition came; and there was this relationship of autonomy. So when we split the research about the exhibition between the artist educators, we had to choose and explore one of the courses/workshops given at that time. I couldn’t choose just one; I chose four: artes do fogo (fire arts) by Celeida Tostes, oficina 3D (3D workshop) by Gastão Manoel Henrique, oficina de moldagens (molding workshop) by João dos Santos and the oficina de materiais sintéticos (synthetic material workshop) by Claudio Kuperman.19 Actually, each one of them had a very specific influence. Celeida had that wonderful poem… “Despojei-me… Cobri meu corpo de barro e fui. Entrei no bojo do escuro, ventre da terra. O tempo perdeu o sentido do tempo […]” (I stripped myself… Covered my body in clay and went. I entered into the bulging darkness, the womb of the earth. Time lost the sense of time […]).20 In my opinion, when you read this it’s basically as if she were living the experience and writing at the same time. As if she were in the middle of the clay while writing that poem…

Clara: I can almost hear that…

João: It’s the description of an experience, a work and an artwork, that is very true to what she felt there. They went to the Pepino beach (at São Conrado) with the oficina 3D and the oficina de moldagem to do the molds and see the beach as a natural sculptural space, as a molding space par excellence, because they would make the molds on the sand and then they would make the fiberglass molds. It was awesome. And so I got in on the act with materials, objects, space, and re-readings of the world around us. Inspired by these re-readings and by my previous experiences I created a two-day course. I wanted it to be a real immersion that worked almost like a residency. The first exercise I suggested during the first meeting was getting to know each other while sculpting a mango. Firstly, this was to discuss the notion of sculpting. “What does it mean to sculpt something? What will you remove…” The mango made a big mess… people opened up there, sculpting, talking, eating, and there was this wonderful smell. And then we thought, “Why don’t we exhibit this somewhere?” Let’s bring this problem out into the space… And then it started to unfold… But this was just an exercise. A very important thing I haven’t mentioned was the workshop given by Antonio Caro, called “taller de creatividad visual” (workshop of visual creativity) that lasted ten days. He said, “If by the end of this workshop we have an affective group and that these people that have never seen each other in life before get out of here knowing each other, talking, staying in touch, the goal will be achieved.”21 It wasn’t a workshop about “I’ll teach you how to create visually.” The only criteria was “to participate, you can’t be an artist.” The idea was to create a togetherness and that’s similar to Parque Lage.

João de Albuquerque. O fazer existir (Making Things Exist). Art is Education Program, Casa Daros, 2014. Photo: João de Albuquerque

Bia Jabor: And it has to do with our pedagogical approach here at Casa Daros, the pedagogy of the encounter. We always emphasize this, that is, this one to one encounter: who is the other we encounter and what comes from this encounter? It may seem extremely simple and obvious, but for a person to be willing and available for an encounter, you have to open yourself up and remove yourself from a series of things. That’s the reason Eugenio (Valdés Figueroa) was so fascinated with Gerchman and with this moment. For quite some time we’ve been researching about what constitutes pedagogical space in the arts and how pedagogical thinking can propel and create educational processes. The children’s education project, which became a very important project for us, takes place through art and it has to do with the pedagogy of listening and with Paulo Freire. To dive into the artistic thinking, not only Gerchman’s but of a group of people and artists who were thinking about learning processes; not necessarily education, but experiential processes. It’s very rich. That’s what feeds us.

Clara: The project (Parque Lage’s) is very generous because it comes from the approach of the school’s founder. The project speaks to this collective sense, each one’s proposal and together, this ensemble is what generated this great work (the School of Visual Arts of Parque Lage).

Jessica: And for you Bia, how did these “encounters” play out in the Laboratory, this notion of the encounter?

Bia Coelho: Generally speaking, it was all very new. I came to Daros at a moment in my life when I wasn’t going out at all. I had just come back from France and I couldn’t deal with Rio de Janeiro. I couldn’t get on buses, walk around… and then the Laboratory popped up and I said to myself, “I’ll just go there and do it.” And it was very hard in the beginning to get here when I wasn’t even going out. It was just me and my books, my books and me, in my room, in my comfort zone. So I got here and there were a lot of excited people I hadn’t met. On the first day they were already playing music and I was like, “What’s going on? Where’s my room?” It was a bit disturbing but then I started to engage myself. I started wanting to get out of the house and come to Daros. Without being romantic, it really was a very important process for me. How many artists were there? Seventeen? Sixteen? Being with so many people, so many ideas, having to deal with them, was a new, but good experience. Sometimes it was very hard for me to come, because they were all very happy, they were always creating something. But I came and it was very enriching. I found myself trying to compare this with that time period, with the video documentary I saw, with the people from Hélio Eichbauer’s class. That’s pretty much what we experienced at the Laboratory, although in a different context. Everyone together doing zillions of things and having to deal with one another, having to participate somehow. It was amazing. I ended up being more sociable.

Contemporary Laboratory: Experiments in the surroundings of Casa Daros, November 5th, 2014. Photo: Jessica Gogan

Bia Jabor: That spectacle conference the Laboratory presented was an opera. Really. It was hard to understand, to live it, but it took guts, because it was very experimental. And without the necessity to be concerned that this had to be something ready or finished or a great performance. It was just another moment of the whole process that was experienced in the Laboratory. And somehow your individual and collective voices were present. That was not easy. At that moment, the question was how to bring together all these voices. Because then you have the personalities, the desires, the anguishes, the expectations, the nervousness, and there’s the institution, and there must be an end; there’s a whole production process involved. The institution needed to know what you needed. For the institution it’s not possible that this open process continues forever. We need to know what time things start, what will happen… so, in that way, really it was really very courageous, everything that we did. We just kept going until we got there. And we were always very inspired by this spirit and the spirit of Parque Lage.

Spectacle Conference: Look, Imagine, Listen, Feel, December 12th, 2014 Casa Daros. Photo: Jessica Gogan

Jessica: On my way here, I was thinking about this resignation letter in the pocket thing. This story about Gerchman always carrying his resignation letter with him in his pocket. How this was also, maybe, a constant permission that permeated everything…

Clara: I guess he was a person – and now I’m talking about him as an artist and as a father – who had his principles and concepts and he was faithful to them. So he was very attentive all of the time. The story about the resignation letter, which became a bit mythical, is that from the moment he was invited to be the director of a free school of the arts during the military dictatorship regime Gerchman creates a defense mechanism, and that’s what the letter is. It means: “I’ll go as far as I can and when I need to, I’ll leave.”

Bia Jabor: But it’s also very symbolic. I understand that this letter in the pocket thing is about getting inside a history, a place, an institution and in its fissures as much as is possible. You can see that very strongly in any project that tries to break down barriers, that is very experimental or that tries to transform, to change. That happens here at Casa Daros. There are these frictions. Gerchman accepted to be in the institution, but with the resignation letter in his pocket, he was saying: “Ok, but the moment I need to leave, that I feel it’s not working anymore…”

Jessica: But maybe these contradictions are necessary in order to create an experimental context, to have a kind of institution where you will come head to head, struggle, a notion of school that you will transform. Something you will invert; where you will do your own anthropophagy.

João: But it also depends on how you are positioned in this institution. Institutions are about instituting, affirming themselves; they are born to establish a discourse, something closed and bounded, and to sustain this for as long as they can. To my mind, when an institution doesn’t have the intention of reformulating itself, like Parque Lage does, it is still born. When an institution is born with a set purpose and reaches this purpose, what does it do next? And then there’s something a teacher of mine (Floriano Romano) from Parque Lage says: “Stop echoing things. Echoing is producing the same things. It is important to reverberate them.”

Jessica: In the USA and Europe there is a very strong institutional history. In Brazil building an institution that has a both living and solid structure, a practice-based thinking that “thinks and acts” as an institution is still embryonic. How can forms of experimentation permeate the institution? The Peruvian curator Gustavo Buntinx talks about this notion of promiscuous museology.22 Another image in this vein that I like a lot, used by English curator/educator Veronika Sekules, is that of the marginalia of medieval texts, where these vibrant drawings/interventions on the margins are in dialogue with the text, not separated from but rather within it, integral to it.23 How then might we breathe marginality and institutionality? For you Clara, directing the Rubens Gerchman Institute, how do you think it might be possible to integrate this experimental thinking with the practice of recovering memory?

Clara: I was thinking about a very bureaucratic thing while you were talking about something so free. Mission, vision, values. I had to do a presentation of the Institute in this superbusiness nothing-connected-to-art thing. Mission, okay, that’s easy. Values, fine. But the vision changes, right? The vision is this live part. Because the vision is where you want to be, it’s what you build. You create a founding document, something that the lawyer will do. You have a previous idea but what does it really become? What are you building there? Consolidating? So, you move forward changing. So that’s it. It’s where you nurture this subtle space to create, to mold; it’s the cracks, the small gaps, that’s where the courage we mentioned before comes in.

Bia Jabor: I think the [Gerchman] exhibition was a tool to recover this memory. Despite the gigantic volume of text I saw that people were interested, they read, watched the videos… Because somehow the result was an extensive research project, the deepening of a history, of a memory, and this became public with the exhibition with the documentary, the interviews, that timeline…

João: It was a history class. It’s funny how something from the past can bring hope. You would look and say: “Was it like that at that time?” It brought more inquietude in relation to what we are living… you begin to wonder, that happened during the dictatorship… and today is like this? And then you start to ask yourself what is this dictatorship we are living in today.

Bia Jabor: In some of the exhibitions we’ve presented [at Casa Daros], we find ourselves returning to the 60s and 70s and seeing this ellipse. It’s as if what had been stirred, re-stirred, “shaken up” and transgressed has still not been totally assimilated today. So we are still in this transition. We are still living this today. And I think the Laboratory tried to do that when with the guests who came here to give classes, like Rafucko and Barbara Szaniecki, for example,24 who talked about the protests in June 2013.25 And then we go back to Gerchman’s time period when there were the protests of 1978 after the fire at MAM, and there’s also a different idea of what “being on the street” means. The last time Brazilians took to the streets for something was the impeachment of Collor.26 The Laboratory was inspired by an idea, a concept, a way of thinking and in principles that nurtured a practice. So, the group, just as much the young artists as the teachers was very much thought out in terms of these fusions, these fissures, mixtures, different views and different artistic languages and contexts. This was very strong in the Laboratory.

Bia Coelho: Having that was great. For example, for me, as I said before, I’m not really interested in doing theatre. And they brought the artist and choreographer Gustavo Ciríaco and there was also the Theatre of the Opressed.27 And those were things I would never have visited if they hadn’t been brought to me. That happened all the time during the Laboratory. I wouldn’t go to Lapa to go to the Theatre of the Oppressed, but I went there and it was wonderful. Often it’s about doing what you know, what’s safe. And for me the Laboratory was like several slaps on the face all the time. And that was good! They were positive slaps. It was very unsettling territory and I embraced it.

João: It takes guts to participate, to get out of your comfort zone. You enter into this state of tension the whole time.

Clara: The exhibition itself… and now I’m talking about Eugenio Valdés Figueroa, curator along with myself, who insisted on exhibition’s design. To present it that way… it took guts, too. The feedback I got from the Casa Daros team in the exhibition was that there were always two types of viewing experiences. Someone would get there and say: “Uh? I don’t get it. Didn’t I come to see paintings, canvas. What’s this?” So there was a moment of estrangement and then the person would come back later and say: “It was awesome. I saw the documentary…” So I guess there was this courage in the presentation of the historical, political and artistic content of the exhibition.

Public visiting the exhibition Rubens Gerchman: With the Resignation Letter in My Pocket, August 8th, 2014 – February 8th, 2015, Casa Daros. Photo: Alline Ourique.

Jessica: But this can also be an artistic and pedagogical proposal to prod and challenge the institution somehow. Institutions have instituted forms of operation. So an exhibition works like this, education like this, communication like this, etc. And when you have something that crisscrosses all this, it’s complicated.

Bia Coelho: And we “prodded” Casa Daros a lot with the Laboratory, right?

Bia Jabor: A lot! Yes! Because when we think about the pedagogical project of Casa Daros it’s like we reached this apex; not of a transgressive nature but rather as if it was pushing up against the edges as much as possible, against the limits of the institution all the time. And we had to do that because somehow it was and has always been in the genesis of the project of Casa Daros, since its conception.28 This place where all these concepts converged, blended and where the limits between curatorship, education and art have to be broken.

João: It was a very fundamental relationship of courage, trust and affection. Because in order to understand anything that comes from another, you need affection and this affection will give you comprehension and comprehension will give you trust and this trust generates autonomy and that’s what generates this kind of thing in a more healthy way. In the context of Parque Lage this moment was perhaps a kind of schism.

Bia Jabor: I think [for us] it was a project in which we managed to have full integration. The course for young artists, involving other institutions and people, external partnerships with the Rubens Gerchman Institute, with Parque Lage School of Visual Arts; artistic thinking reverberated in the creative encounters… It really was a unique moment in the entire history of Casa Daros and that’s why it was so hard, because there was this fusion and the limits were broken…

Jessica: I would like to close with a question. We have been talking about this moment in the history of the School of Visual Arts, about how we draw from this moment as a way of thinking about our present. Now, a question about the future. What seeds will you keep from this experience? How do you think about this past as a thought-form of a future?

Bia Coelho: I guess I won’t be able to go back to the quietness I was in before the Laboratory. I think that’s the strongest thing about it. I won’t be able to go back to the place I was, even if I go through experiences that lead me to a similar place. I’m outside now. You can’t close your horizons after you open them, right? The space became too small to me.

Clara: I won’t be able to stop researching about this subject. I’m crazy about it, opening doors. It’s given me a hunger to carry on.

João: I think that for me it’s very similar to what Bia said, about not fitting anymore. There’s a song by Arnaldo Antunes that says in the chorus: “everybody has to not fit in order to grow.”29 When you don’t fit anymore, you grow. Anyway, what stays for me is this.

Clara: I would even say that we brought a problem to the new management of Parque Lage because we raised a lot of issues. Think that there’s a new director, board, a new reformulation… Where do they want to be? What’s the direction?

Bia Jabor: Some things will stay. At least for us at Casa Daros the importance of research became very strong. Because this exhibition was born only out of very intense research, and the eternal collaboration of the artist in the pedagogical process. There’s no dissociating this anymore. And curatorship between art and education as well, everything is a bit “enmeshed” together. These questions were just further concretized with this project. The importance of being close to the production of young artists. We just go on shaping it. We need to be like water, go through the cracks, a liquid management, more permeable.

_

1 Eugenio Valdés Figueroa, co-curator of the exhibition Rubens Gerchman: With the Resignation Letter in My Pocket, and former director of art and education at Casa Daros. Excerpt from the press release for the exhibition.

2 The Rubens Gerchman Institute is a nonprofit organization created in 2008 with the aim of upholding the legacy of the artist. http://www.institutorubensgerchman.org.br

3 Figueroa op cit.

4 Sergio Santeiro is a filmmaker and activist in independent Brazilian cinema. As a director and screenwriter, he has exclusively made short experimental films. He is a professor at the Universidade Federal Fluminense where he also headed the department of cinema and video (1996-99) and he directed the Instituto de Arte e Comunicação Social (1999-2003). He taught cinema at the School of Visual Arts of Parque Lage from 1975 to 1979. http://www.cinevi.uff.br/index.php/corpo-docente/sergio-santeiro

5 Excerpt of the text written in 1976 by the artist Rubens Gerchman for the exhibition Espaço-Lúdico (Ludic Space) a retrospective of the 13-year career of the cenographer Hélio Eichbauer held at the School of Visual Arts, Rio de Janeiro. Published in the exhibition catalogue O Jardim da Oposição, 1975-1979. EAV/Parque Lage, 2009.

6 Excerpt of the document “O que é a Escola de Artes Visuais” (What is a School of Visual Arts), by Rubens Gerchman.

7 Escola da Ponte is a Portuguese high school situated in São Tomé de Negrelos – Santo Tirso, in Porto (Portugal) and is coordinated by José Pacheco. The school has educational practices that distinguish it from traditional models. There are no grades, cycles, classes, manuals, tests, or lessons. The students gather according to the common interests in order to develop research projects.

8 Hélio Eichbauer is one of Brazil’s most important set designers. In the 60s, he studied scenography and architecture in Prague under the orientation of Josef Svoboda, who was then considered one of the most important professionals in the area in the world. Back in Brazil, he designed operas, ballet performances, prose theatre, and concerts of Brazilian popular music. He did set designs and costumes for plays and dance performances and for many of the most famous experimental projects in Brazil in the second half of the 20th century. In addition he has also done set design for the musicians Chico Buarque and Caetano Veloso. At Parque Lage, Eichbauer was one of Gerchman’s key partners in the execution of a free and experimental art school. http://enciclopedia.itaucultural.org.br/pessoa349629/helio-eichbauer

9 Rosa Magalhães is a Brazilian teacher, artist, costume designer, set designer and carnavalesca (term for set and costume designers for the samba schools at Carnival). She created a strong identity for the school of samba Imperatriz Leopoldinense, with whom she won five titles. Nowadays she is a carnavalesca for São Clemente.

http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosa_Magalhães

10 In her “poetic spaces” and “magnetized spaces,” Lygia Pape moved her work outside of museums and galleries, and in her workshops with the students at Parque Lage she embraced an experimental spirit of discovery outside of the classroom, often working collectively and creating web-like constructions. In 1976, the artist defined “poetic space” as “any language in the service of ethics.” Lygia Pape. Statement. EAT Me: a gula ou a luxúria? April 21, 1976. In Manuel J. Borjas-Villel and Teresa Velázquez (curators). Lygia Pape: Espaço Imantado. São Paulo: Pinacoteca do Estado, 2012, p. 372. For more information about the artist: http://lygiapape.org.br/pt/lygia.php/.

11 On April 1, 1964, a military coup deposed the president João Goulart and established a dictatorship in Brazil which prevailed until 1985 and was marked by serious violations in human rights, repression, censorship, and suppression of constitutional rights while simultaneously opening up to foreign capital.

12 Excerpt from the video interview given by Rubens Gerchman presented in the exhibition Rubens Gerchman: With the Resignation Letter in My Pocket, August 2014 – February 2015, Casa Daros, Rio de Janeiro.

13 Ney Matogrosso is an important Brazilian musician. He was a member of the band Secos & Molhados during the military dictatorship and, after breaking up with the group, continued on as a solo singer and built a solid career as a musician, lighting designer and actor. http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ney_Matogrosso#In.C3.ADcio_da_carreira

14 Heloisa Buarque de Hollanda is the coordinator of the Programa Avançado de Cultura Contemporânea (PACC/UFRJ – Advanced Program in Contemporary Culture at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro) and the director of the publishing house Aeroplano. Her field of research explores the relation between culture and development with particular focus on the areas of poetry, gender and ethnic relations, marginalized cultures, and digital culture. She has written a series of books and is an important critic of Brazilian culture. She co-curated along with Hélio Eichbauer the exhibition O Jardim da Oposição, which was organized in 2009 at Parque Lage as a tribute to Rubens Gerchman. http://www.heloisabuarquedehollanda.com.br/exposicao-o-jardim-da-oposicao-2009/

15 Jards Macalé is a multidisciplinary artist active for over 35 years. He is a composer, singer, musician, producer, musical director, arranger, and actor. He recently composed for the play Os Sertões, based on the romance by Euclides da Cunha.

http://www.jardsmacale.com.br/jd_biografia.htm

16 Charles Esche. “Include Me Out: Helping Artists to Undo the Art World.” In Steven Henry Madoff ed. Art School (Propositions for the 21st Century). Cambridge, Massachusetts / London England: MIT Press, 2009, pp. 101-112.

17 In July 1978 the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro (MAM) tragically lost almost all its collection due to a devastating fire. The museum lost approximately a thousand art works of its permanent collection, including those by Picasso, Dalí, Matisse, and Magritte, among others and works featured in a temporary exhibition at the time by the Uruguayan artist Torres Garcia. The museum went through a rebuilding process and nowadays it is possible to see some of the art works that were restored, including those of Lygia Clark, Djanira, Nelson Leirner, Alberto Magnelli, and Jorge Páez Vilaró. http://memoriaglobo.globo.com/programas/jornalismo/telejornais/jornal-hoje/incendio-no-mam.htm

http://mamrio.org.br/exposicoes/acervo-mam-obras-restauradas/

18 Gabriella Besanzoni (1888-1962) was a classical singer born in Rome. She lived part of her life in Rio de Janeiro after marrying Brazilian businessman Henrique Lage who built the small palace inspired by Roman palaces that was to become Parque Lage. Parties and soirées were frequent in the house and Gabriella would sing to her guests during the events. After her husband died, she returned to Italy, where she started to teach singing. Due to being a foreigner and having no children, she could not inherit part of the assets left by Henrique Lage. In 1957, the place was protected by IPHAN (National Institute of Patrimony). Formerly the Institute of Fine Arts, in 1975 Parque Lage become the School of Visual Arts. Today, the park in which the building is situated receives many tourists and there is also a trail to Corcovado.

http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabriella_Besanzoni http://www.blogdoims.com.br/ims/parque-lage-em-1944-por-roberta-zanatta

19

Oficina de artes do fogo (Fire arts workshop)

Profesor Celeida Tostes

For this workshop the sculptor Celeida Tostes expanded traditional pottery practices to more organic processes of immersion in nature: of oneself, of the other, and of techniques of working with the clay and experimenting with materials. She aimed to integrate with the other workshops where spatial thinking was practiced, like the oficina de modelagem and the oficina de materiais sintéticos. Her creative process as an artist richly intertwined with her pedagogical practice and clay was the material with which Celeida sought this transcendence.

Oficina Moldagens (Molding workshop)

Profesor João dos Santos

This workshop was based on the concept of appropriation and “recycling” of objects that have “a capacity of use considered extinct” and on the use of materials that were considered “on the margin of industrial production.” The idea of the 1978 program was to create interventions with objects and materials that could generate physical and contextual changes in form, function, and unity of the object (readymade/Duchamp principle). “We consider working with material not only as a creator, but as a transformer, and man’s intervention on and with this material, takes its position in relation to nature (raw material) or as an insertion at the core of the production circuit, be it industrial or hand-made.”

At Pepino beach in São Conrado, between the 28th and 30th of November 1978, the collective proposal Molde Móvel: fiberglass moldado na areia (Moveable mold: fiberglass molded in the sand) as part of the project Área Aberta sponsored by Funarte was presented as an integrated work in collaboration with the oficina artes do fogo (Celeida Tostes), the oficina de moldagem (João dos Santos) and the oficina de materiais sintéticos (coordinated by Cláudio Kuperman). The project was about “a unique experience because of its non-elitist (intramural) quality that was against any idea of gallery (art market),” in which the artists suggest “occupations in pre-existent spaces,” seeking other dissemination outlets for art. As part of the project, the students from oficina 3D – oriented by Dinah Guimaraens, Gastão Manoel Henrique and Lauro Cavalcanti – created the exhibition Ritos de passagem (Rites of Passage).

20 Excerpt from poem by Celeida Tostes. Exhibition catalogue. Passagem, 1978.

21 Oficina de criatividade visual (Workshop of visual creativity). Antonio Caro, Casa Daros. July/August 2013. Antonio Caro is an important conceptual Colombian artist. He gave a workshop for “social multipliers” (educators, activists, members of social organizations among others) and teachers, as well as people who were interested in arts and the general public. The goal was to stimulate creativity, reinforce and motivate a collective and critical spirit.

22 Gustavo Buntinx. “Qué es y qué quiere ser micromuseo (“al fondo hay sitio”). Fragmentos recombinados de textos vários.” In: Manifiesto de viaje. Available at: www.micromuseo.org.pe/manifiesto/index.html

23 In her essay “The Edge is Not the Margin,” curator and educator Verônica Sekules explores an analogy between the meanings of margins in medieval texts and an experimental and critical pedagogy, where the margins could be used to celebrate, criticize, subvert, or challenge the ideas that are in the central text. In: Helen O’Donoghue ed. Access. Dublin: Irish Museum of Modern Art, 2009, pp. 235-259.

24 Rafucko makes political satire videos and performances. At the beginning of 2014, he succeeded in crowd funding a campaign and was able to produce a series of interviews for a web talk show (Rafucko/Rafucko’s talkshow). Barbara Szaniecki has extensive experience in graphic design and teaches at Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro. She is an activist and involved in the free university Universidade Nomade, organizing events and forums and co-editing their publications. She is the author of the books Estética da multidão (Civilização Brasileira, 2007) and Disforme contemporâneo e design encarnado: outros monstros possíveis (Annablume, 2014).

25 In 2013, the streets of many Brazilian cities were filled with protests, known as jornadas de junho (days of June). The protests started because of a price increase in public transportation and in turn began to incorporate multiple issues. The protests took place in a context of the big business investments and real estate speculation associated with the mega events of the 2014 World Cup and the forthcoming 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. Key highlights were the MPL (Movimento Passe Livre – collective movement fighting for free transportation), the direct action tactics of the black blocks and the multiple independent media collectives that reported especially on the unjustifiable violence of the military police against the protesters – a reality that the hegemonic media hid or manipulated.

26 In 1994, a popular mobilization with great appeal amongst Brazilian youth – known as “caras pintadas” (painted faces) – took to the streets to demand the impeachment of the president Fernando Collor de Mello. Due to the strong evidence of corruption, the Associação Brasileira de Imprensa (ABI), the Ordem dos Advogados do Brasil (OAB), the Central Única dos Trabalhadores (CUT), and the União Nacional dos Estudantes (UNE) made an official request asking for the removal of Collor from the presidency. The congress organized a parliamentary committee of inquiry (CPI) to review the facts. The impeachment was passed; however, in order to not lose his political rights, Fernando Collor resigned from his position.

27 The choreographer and contextual artist Gustavo Ciríaco is based in Rio de Janeiro and works in Latin America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East in transversal projects and collaborations involving architecture, visual arts and art of the spectacle. His projects are oriented by the context in which they happen and by the poetry of the materiality within each situation. The Center of Theatre of the Oppressed (CTO) is located in Largo da Lapa, Rio de Janeiro (31, Mém de Sá Avenue). The institution was established in 1986 and conducts research on and disseminates the specific methodology of the Theatre of the Oppressed in laboratories and seminaries. Created by Augusto Boal, the Theatre of the Oppressed is a theatrical method based on acting within real life situations and stimulating the exchange between actors and viewers through a direct intervention in the theatrical action.

28 The first sketches of the Casa Daros project were made by Eugenio Valdés Figueroa between 2001 and 2003 and were inspired by the pedagogical principles of Paulo Freire and the work of Instituto di Tella (Buenos Aires), Domingos da Criação (MAM/RJ) and Casa de las Américas (Havana). It’s a project that understands the close relationship between art and education, a space where art is understood as a vehicle for learning and education as a creative process.

29 Arnaldo Antunes. “Cabimento.” Written by Arnaldo Antunes and Paulo Tatit. Chorus: “como toda gente tem que não ter cabimento para crescer” (like everyone you need to not fit to grow).