Reading and Thinking Out Loud: Exercises in “Voices of the South” Civic Rights

Renata Targino

Listening to each other collectively affirms the value and uniqueness of each voice.

bell hooks1

[…] it is through words and work that action-reflection happens, not in silence.

Paulo Freire2

The public school, under normal conditions, is an intense space of coexistence and multiple differences, some of which cause discomfort, generate discriminatory attitudes, and conflicts that, it is hoped, the school itself will face and resolve. This plural environment, comprising [these] often ignored voices, is also an institution that reproduces old ways of thinking, habits, and practices that maintain the structures of power to which we are all subject in the current model of society in which we live.

The community where I work as a teacher is on the periphery of the periphery. Once occupied by estates belonging to the colonists of centuries ago, it is an area of São Gonçalo that has recently experienced disorderly growth and urban violence. The region shows us the [many] social inequalities that have not yet been overcome. Although society is dynamic and values have changed quickly in times of liquid modernity, it is still common to find families who raise their daughters for submission and their sons for domination.

Students in the classroom often reveal this patriarchal education. Just create an environment conducive to attentive and respectful listening and let them speak. In conversation circles and text production activities, these voices come to the fore and [often] clash with others considered as non-normative, with whom they share the same space. We see then, that while the structure of open dialogue may be offered, everyone does not easily accept it. Challenging long held beliefs, therefore, can cause questions not only about old stereotypes but also the family itself.

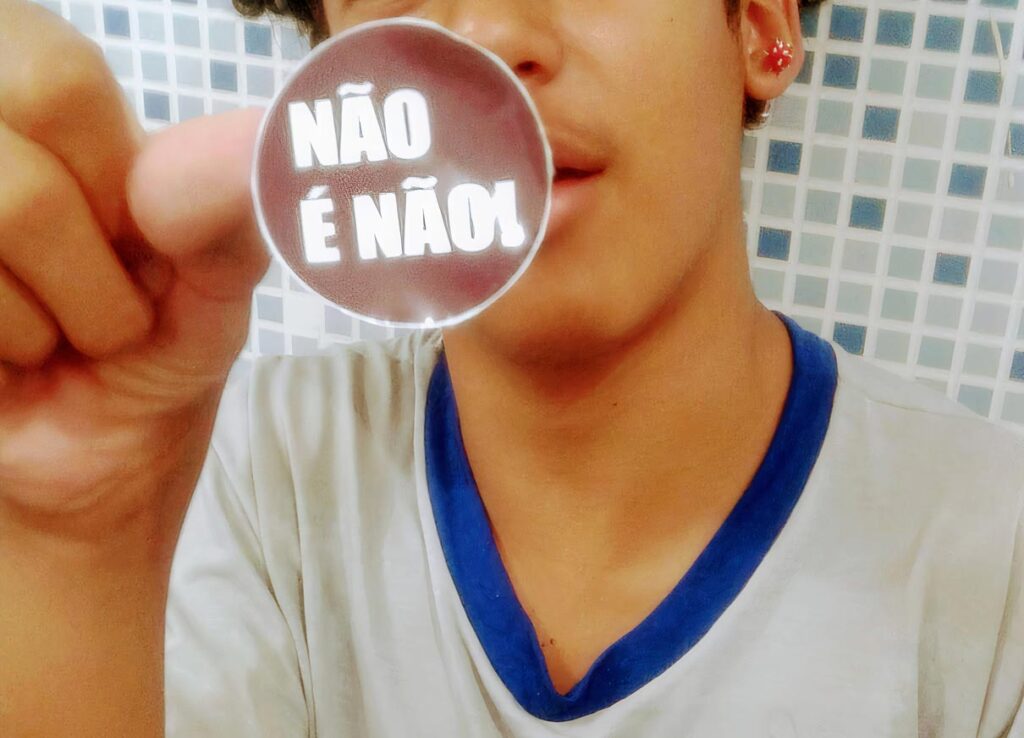

To contextualize the seriousness of the gender issue, in 2016, a woman was gang-raped in a bar near our school – security cameras caught men, carrying rifles, practicing the crime. The case gained media attention and caused wide spread perplexity and astonishment. However, among our own, I found a deafening silence. Uncomfortable, I talked to some classes that, in general, blamed the victim for the violence suffered, naturalizing the culture of rape. Society’s expectations regarding the work that education professionals carry out are numerous, and it is common to exceed the limits of curriculum guidelines. However, this desired teaching expertise does not always encompass the dynamics of social relations in a school community. Perhaps it is not in the interest of some sectors that teachers and professors deal with topics such as sexism and lgbtphobia, for example. Even so, surprisingly, in countless interviews that reflect crimes of gender violence, we hear the voices of lay people and authorities reverberating: “the school has a fundamental role in solving the problem”.

Amid other types of inequalities, under precarious conditions of resources and lack of training, how does the school learn / teach empathy, solidarity, and respect for difference? What is the role of pedagogical teams, public management, and universities? If we look at the data that point to an increase in gender-based violence in Brazil, we can imagine that the actions carried out are timid and have negligible effects at the national level.

It is in this scenario that the professional master’s program Profletras emerges as a possibility to change perspectives, due to the impact that it can generate both at the school and university levels, fostering research that seeks to point to problems and possible solutions for Brazilian public education, while valuing both the formal and informal scientific communities that the program represents.

When I became a teacher-researcher, it became urgent for me to investigate the gender and power relationships that occur in the school environment in order to mobilize students to engage in a political-pedagogical movement for structural changes, promoting gender equality from context of the classroom itself. As Malala Yousafzai spoke at the UN, I also believe that “a book, a pen, a child and a teacher can change the world”. Bringing the Pakistani activist’s voice reinforced our ideal of change as one brought about by action-reflection, particularly as it showed the class that student voices can be very powerful.

Reading the works of the authors who are exponents of intersectional feminism was inspiring – in particular, the Brazilians Lélia Gonzales, Djamila Ribeiro and Márcia Tiburi, and the Americans Angela Davis and bell hooks.3 Reading and interpreting out loud, excerpts from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Maria da Penha Law, and other legal provisions that support the promotion of gender equality and social justice also reinforced that the voices of everyone and each individual have the same weight and importance.

It is necessary to demonstrate that the student voice is just as valid as that of the teacher. To practice critical pedagogy is to design forms of communication that are not hierarchical, but dialogical. The critical feminist pedagogy that we collectively constructed in the classroom consists of problematizing the unequal relations of access and power that exist between girls and boys, men and women, both in our society and in the reality created in the works of fiction we read, interpret, and discuss.5

In reading and text production classes the big star is the text itself. Shared reading creates moments that generate opportunities. Reading aloud is part of this process of appropriating what has been read, the texts’ particular impressions, its place of speaking and listening to versions of the other, and also, of oneself. Reading and commenting on what they read, students write about the possible meanings that emerge from the text.

In this participatory proposal, everyone has the right to a voice. Theoretically, this exercise of democratic education, one that aims to be free from multiple oppressions, immersed in the reflections of Paulo Freire and bell hooks, is powerful and transformative. However, to affect awareness-engagement and bring about effective change is a struggle. According to the words of the philosopher Marcia Tiburi: “Struggle is the action of desire that politicizes us”.6 The word struggle presupposes a kind of dialogue, that is, it communicates and marks positions. In our context, the word struggle makes explicit the political content of teaching and learning.

According to bell hooks, the practice of dialogue is one of the ways in which we can “cross borders, barriers that may or may not be raised by race, gender, social class” and other differences.7 Only frank and democratic dialogue is capable of transforming conflicts into learning, so that we at last reach a more balanced and fair world for girls and boys, where they can be free to be who they are and can contribute with all their powers to the construction of a more empathetic and supportive society that respects differences.

Become aware, empower yourself, educate yourself – with autonomy, but never alone. Reading and reflection combined with action, connected to struggles, transformed our teaching model and the modes of this group’s learning. This in turn began to multiply as the students combined the knowledge they acquired with that of other collective efforts, demonstrating that in this field all and everyone could be heard. And who records the sound of these invisible voices? Who formulates these curricula hidden in singular practices, deeply engaged in the exercise of full citizenship from the “voices of the south”?8 The teacher trained in social justice in dialogue with their students.9

***

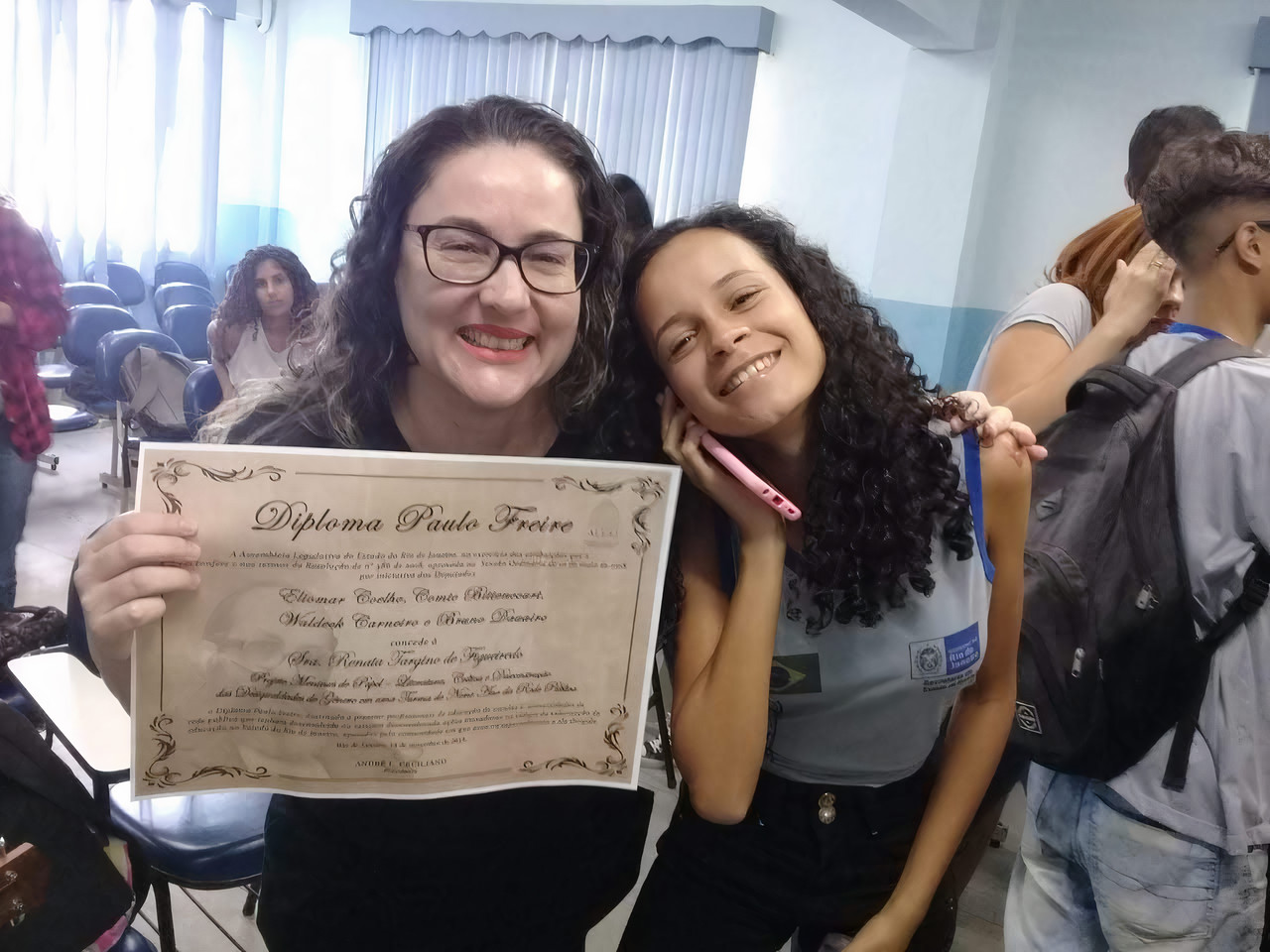

Renata Targino

Is a teacher of Portuguese language and Literature at the public school network of the state of Rio de Janeiro. She has a Master of Arts from the Faculty of Teacher Education (FFP / UERJ) and is a member of the research group “Teacher Training, Languages and Social Justice” (PROFJUS). In 2019 she received the Paulo Freire Award for innovative initiatives in the category “Pedagogical Experience in Elementary Education”, offered by the Education Commission of the Legislative Assembly of Rio de January (ALERJ).

1 bell Hooks, Ensinando a transgredir: a educação como prática da liberdade (São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2018).

2 FREIRE, Paulo Freire, Pedagogia do oprimido (Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2015).

3 Intersectional feminism is influenced by the writings of Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Law professor and especialist on questions of gender and race.

4 Available online: https://jornalggn.com.br/direitos/pelo-direito-dos-meninos-de-silvia-amelia-de-araujo/.

5 For example: “Procurando firme”, children’s book by Ruth Rocha, published for the first time in 1984 (Nova Fronteira) and “A moça tecelã” by Marina Colasanti.

6 Márcia Tiburi, Feminismo em comum, 7. Ed ( Rosa dos tempos: Rio de Janeiro, 2018).

7 HOOKS, op. cit. p. 1.

8 A reference to “sulear” [meaning oriented by the south (and interests of the South] used by Paulo Freire [to counter the Portuguese term “nortear” which in common parlance means to orient or guide and leaves the interests of the North unquestioned]. Others have pointed to the importance of a “Global South perspective” (Raewin Connell) or “epistemologiies of the south” (Boaventura de Souza Santos).

9 The question of gender equality as a question of social justice a key emphasis for Paulo Freire that also includes questions of race, class, security, alimentation etc. Teachers aware of their social context striving to transform it are committed to this theme. See ZEICHNER, Kenneth M. Zeichner, Justiça Social: desafio para a formação de professores (Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2008).