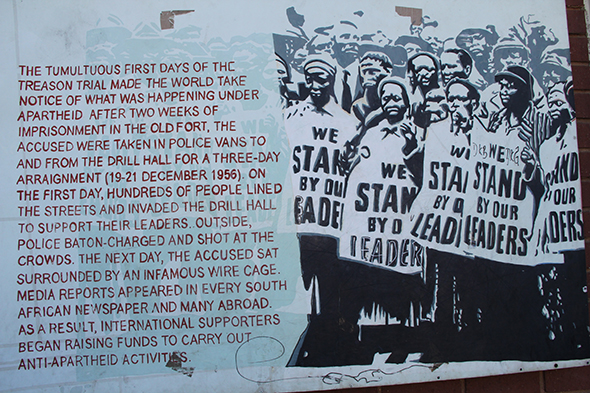

One of the outdoor informational panels made by the Joubert Park Project and collaborators circa 2004. Half of these have been damaged and/or disappeared due to lack of security measures, vandalism or petty theft. Photographer unknown

Biblioteca Keleketla! Overview

k!kollage (excerpts, revisions and citations from texts written by/about/for Keleketla!)

Keleketla!

Keleketla! Library is an inter-disciplinary, independent library and media arts project. We initiate and provide platforms for collaborative, experimental, multi-media projects with local, national and international artists, cultural practitioners and activists. Keleketla! is a Northern Sotho/Pedi word that is a response to the beginning of a story, something that you say back to the storyteller’s “Once upon a time.” It is an acknowledgment, a consent that “I am here, willing to listen to your story with active participation.” The project began in 2008 as a once-off collaboration with Bettina Malcomess, Rangoato Hlasane, Malose Malahlela, and the Joubert Park Project (JPP), with financial support by the National Arts Council.1

Site

Based at the historic Drill Hall precinct in Joubert Park, Johannesburg, Keleketla! was formed to create access to the employment of arts and media strategies as alternative education models and tools. Just like the essence of Keleketla! the word, the space hoped to engage in an active dialogue with its immediate community by reflecting the inner city through participatory projects. Built on the ruins of a “native prison” in 1904 as a military base buttressing British colonial power after the Anglo-Boer War, the Drill Hall was involved in the marshalling of forces in both World Wars and the quelling of civil unrest and various miners’ strikes in the first decades of the twentieth century. In 1956 the building was turned into a courtroom for the Treason Trials. In the 1970s and 80s, it served as an important site for the conscription of young white men into active duty in the border wars and the suppression of internal resistance to Apartheid. Abandoned by the Apartheid military in the early 1990s, the Drill Hall was invaded by squatters, leading to two fires and a number of fatalities. From 2002-2004 the Drill Hall was redeveloped as a heritage site through the efforts of the City of Johannesburg. While the ambitions of the city are a story for another day, it is on these layered grounds that a “library” was founded, and continues to evolve on a daily basis.

While the Keleketla! Library collection consists of over 3.000 books of all subjects, its programming positions the project as a space for critical inquiry and art practice. In other words, the library is neither a duplication of state information services nor a supplement of social development efforts. Rather, the project is a space that contributes new knowledge on historical and contemporary experiences in an African city, building an archive of quality, socially engaged art practices.

There are three core programs, each interacting with the other, featuring a lending and reference library, an after-school program and a series of experimental projects. As the after-school program is discussed separately in this series of case studies the present essay/reflection will explore both the library context and practice and a number of past experimental projects.

The Library

Starting a library means starting a collection. Keleketla! Library began collecting with a call for donations of books on all subjects. Given that Joubert Park is a dense and dynamic Pan-African neighborhood, we asked ourselves what kind of a collection should this library present to its audience?

It is argued that South Africa’s over 1.800 public libraries do not cover the countrywide need for information. Meanwhile, modes of knowledge transmission are changing with technological influences and trends in global communications. In the post-colonial context in which we find ourselves, literacy is a tired term, even more so the notion of illiteracy. Internet connection is worse, stuck between socio-economic inequality and lack of political will. Illiteracy in our case is the result of a deferred decolonization project that is bound to take ages to move with the times.

Thus some of our “archives,” starting with the physical historical infrastructure itself, were made, for example, to speak to high school History curriculums via the after-school program in art and media or they manifested as a rereading of South African music history through a temporary orchestra project. In short, the program celebrated self-organization and the relevance of knowledge – we asked, who creates knowledge and for what purpose?

Given this, access to books was a natural point of departure for the project. Keleketla! programming tests knowledge production methods with sensitivity to context, while also recording societal change. We explore ways to continuously share knowledge and encourage experiments on new methods of knowledge dissemination that build on contemporary practices. The library appreciates that technology and the movement of people challenges books and conventional ways of reading. Yet, naming the project Keleketla! Library conflates two ideas/forms/medium in friction and harmony: storytelling and books. Thus, alongside books in the traditional lending space, programs have taken place since the establishment of the project in 2008 in the form of an after-school program (Keleketla! After School Program or KASP) and once-off/serial projects. In this way, an “educational” space with younger citizens exists parallel to that of practitioners in “training.”

The traditional library space with donated material is well used by members. Painting on walls by Johannesburg-based artist Meghan Judge. Photo: Rangoato Hlasane.

A Library That Writes into Its Collection

For a sound project, an audio play reenacted the Treason Trial and related narratives in order to explore a chapter in the liberation struggle. Through the process, members from what appeared to be three distinct disciplines namely, Music & Sound, Audio Play and Creative Writing formed a feedback loop through crossovers in writing, research, recording, and publishing. Throughout the first five years of Keleketla! the programs produced a growing archive. In retrospect, Keleketla! is a library that produces its own catalogue. The traditional and the technological collide as a matter of contemporary reality, not tension. While this catalogue exists as an experience embodied by those who have passed through the doors and/or experienced the programming ephemerally, a large collection of tangible material is available for a dialogue on health, art, community, resistance, history, place, action, power, knowledge, and creation.

What To Do with History?

Keleketla! Library possesses historical material courtesy of the Mayibuye Archives, Medu Art Ensemble and Museum Africa. We have secured rights to use the material for educational purposes within the program. Furthermore, the JPP has produced a remarkable amount of artwork and research around the Drill Hall and the Treason Trial. JPP has also granted Keleketla! full permission to use the art collection and publications with the educational program. Material referenced in the program is used to enhance the experience of each project. The KASP members reflect on the value of selected material and imagine strategies to contribute new perspectives on historical artifacts and facts. History is seldom repeated in the music and dance productions that emerge out of the program. The short stories written by young learners explore issues such as teenage life, loyalty, ambition, religion, history, and (dis)ability. Narratives found in the creative work are sophisticated, expressive and not mere representations of history.

For example, Phomolo Sebopa’s “Bibi the Special Swimmer,” a story of a person’s disability, is handled with the utmost sophistication, sensitivity, critical awareness, and pride. There is no victimhood or self-pity; it is full of voice and dignity. It is important for a people to assert their own reality in relation to the world, and the arts enable such self-realization. The outcomes of KASP are valuable as they provide insight into young people’s perspectives, develop skills, expose new talent, and nurture growth. We believe heritage can be used to evoke nostalgia, provoke anger, encourage healing, and avoid repetition. History is believed to be the story of the victor and as a result it leaves multiple perspectives out of the historical narrative. When art is permitted to reflect on history, people can imagine alternative stories, enabling fertile ground for discussion and reflection. Heritage thus initiates dialogue, allowing us to see heritage education as a new form of knowledge production.

Experimental Projects

Keleketla! projects expand on the notion of a library/text by speculating on what constitutes knowledge and how it can be disseminated. The cross-genre approach that hinges on public engagement not only produces innovative methods, but also builds audiences and expands literacy from its traditional definition.

Our projects are characterized by emphasis on process. The co-founders started by organizing weekly hip-hop drenched performance platforms in the bedrooms of their student accommodation building for five years before the establishment of Keleketla! Library. The activities were grounded in the most sincere desire to create and share while maintaining autonomy from academic discourse or funding frameworks. This way of working offered a unique entry into the public life of Keleketla! Library, informing the kind of programming that privileges the context in which we work. Projects dealt with the public issues of space and funding in regards to the need to create. Thus, our programming is educational. Co-creation of knowledge becomes embedded in the projects that are collectively “curated.” We will look briefly here at some of these projects.

Stokvel

In 2009, Keleketla! and collaborators in music, visual art, craft, fashion, cuisine, and more explored a traditional, communal economic model called Stokvel. Stokvel is a collective pooling of funds amongst a group of people who help each other achieve financial goals. As a group of activists and cultural workers within a precarious system, we wanted to investigate how such a “traditional” practice could be adapted in the arts.

Stokvel turned Rangoato Hlasane’s home into a place of art for one day on 06 June 2009. Photographer unknown.

Stokvel #1, which took place at (then) Rangoato Hlasane’s home, was an experiment in collective curating with visual artists, musicians and activists. At the time Keleketla! had kick-started an art auction to raise funds. The contributing artists donated exhibited work towards the fundraising auction, thus the work on show was shared for the last time with a public before becoming part of private collections.2

Stokvel #2 took place at Point Blank Gallery, the Drill Hall in the context of a transatlantic exchange with the folks at the 2009 Allied Media Conference in Detroit. With a focus on music production, dissemination and the notion of independence, Stokvel #2 invited two “bedroom studios” to dislocate for one day, enabling poets, writers and emcees to think, exchange, record, and perform together in front of a live audiences via Skype.3

Stokvel #3 consolidated the first two experiments into an after-party to the art auction that raised over ZAR30 000, featuring Johannesburg-based bands and DJ’s.4 True to the barter system of Stokvel, the last installment was seen as a gift to everyone involved in the experiment, while at the same time it was a platform in itself for performing artists.

As a project, Stokvel dealt with the notion of culture and development. It was concerned with the promotion of independence through self-organization. It wanted to develop professional practice in literature, performance, visual art music, design, and more, while also using culture as an organizing tool that responds to and is sensitive to context.

SKAFTIEN

Johannesburg-based performance art band The Brother Moves On performs at the first Skaftien, February 2011. Photo: Brett Rogers

SKAFTIEN, explored at the beginning of 2011, was, in a sense, a further re-exploration of Stokvel. From the SKAFTIEN website:

SKAFTIEN is a recurring community-based meal that generates and democratically awards micro-grants for creative, experimental and innovative arts projects in Johannesburg and Cape Town, South Africa. At each SKAFTIEN, attendees purchase a ticket for which they receive a meal, a ballot and entertainment. During the meal, the diners listen to five proposals so as to cast up to two votes for their favorite project/s. We are interested in ideas that, in their experiential form, may not attract funding from conventional sources, yet contribute fresh perspectives on the relevance of the arts. The winner of the popular vote is awarded a grant funded by the proceeds of the event, and is asked to present the manifestation of the project at the next event.”

Audience members listen carefully to Skaftien #1 presenters at the Drill Hall rooftop. February 2011. Photograph: Brett Rogers

In a climate where the life of art practice is stuck between a prescriptive state policy and a shaky international donor mentality, SKAFTIEN explored how the art community could support itself. While both the Johannesburg and Cape Town versions of the project received critical acclaim and were welcomed by its diverse public, the organizing proved to be a labor of love. Ultimately, both versions ceased after their third reiterations in 2013. Nonetheless, the project is dearly missed and will surely resurrect in a new form, just as SKAFTIEN revised Stokvel.

Judy Seidman speaking on public art in the context of SKAFTIEN #3, a reflection the model and its potentialities. 24 February 2013, Makhwapheni, Stevenson Gallery, Johannesburg

Nonwane: Passages, Tempos and Spectacular Ways of Dying

The Nonwane residency was a walk-in research/social space that explored the texts Welcome to Our Hillbrow (Phaswane Mpe, 2001), The Quiet Violence of Dreams (K. Sello Duiker, 2001) and the piano solo album Darkness Pass (Moses Taiwa Molelekwa, 2005) at the Wits School of Arts’ Substation gallery. Furthermore, the residency was an encounter of screenings, listening sessions, walks, talks, jammings, recordings, workshops, readings, writing that produced conversations, parties, texts, and memories. These encounters were a method of research towards an unusual performance, linking the neighboring Hillbrow suburb and Wits University.

Nonwane took as its point of departure a suicide scene from the late Phaswane Mpe’s 2001 novel, Welcome to Our Hillbrow. The book deals with issues of xenophobia, suicide, sex, HIV, and love. A reenactment of a suicide scene from the book took place on the rooftop of the Summit Club in Hillbrow as a culmination of the residency, simultaneous to a work by the Joburg-based performance “band” The Brother Moves On, revisiting the music of the late Moses Taiwa Molelekwa.

Thath’i Cover Okestra

In the early 90s, a new form of urban dance music was born in Johannesburg, its influence spreading throughout the Southern African region. Speaking to youth in the language understood and spoken by youth, the music took the baton from previous genres that innovated indigenous sounds of the region.5 Kwaito embraced technological advances in music production and infused them with a political sensibility.

Pre-performance site rehearsal for the first Thath’i Cover Okestra project with Mngomezulu Neku on bass, Tito Zwane on electric bass guitar, Zweli Mthembu on rhythm guitar, Nkosinathi Mathunjwa on keyboard, Kgomotso Mamaila on vocals, Tiko Ngobeni on percussions and didgeridoo, RubyGold on vocals, Gwyza on vocals, Sibusiso Galaweni on drums and Tebogo Mokoena on saxophone. Produced by Keleketla’s Malose Kadromatt Malahlela and Rangoato Mma Tseleng Hlasane, the music education project included a collaboration with the Alexandra Field band ensembles on two songs. 5th May 2011, The Drill Hall square. Photo: Tolo Pule/Manifest

In 2012, as part of the Goethe-Institut Johannesburg’s “Shoe Shop” project, Keleketla! Library commissioned 12 young musicians from different Johannesburg-based bands to explore the formative Kwaito “catalogue.” The focus was to explore the political and spiritual sensibility of the 90’s music with the aim of creating a live performance at the Drill Hall. The project’s impact was far reaching, and later in the year the young musicians were invited to the Cape Town-based Pan African Space Station festival of the Chimurenga Magazine, this time in collaboration with Cape Town-based musicians.

It is important for Keleketla! to create these kinds of projects as a parallel to the library and KASP projects. Speculative and experiential they present models and proposals that speak to notions of audience, the financing of art institutions and relevance responding to specific local contexts.

Forward Looking

In this phase of the project, we have begun a post five-year reflection requiring the archiving of all material. Part of this process involves revising how we read our own work. Recently Keleketla! self-published the second edition of our 56 Years to the Treason Trial: Intergenerational Dialogue as Tool for Learning. The 2012 publication consolidated our education work from 2010 to 2012, looking at the methods, processes and applications in book form, which included conversations between elders/historians and members of the after-school program and school learners. The information in the book conflated national history with local context as briefly reflected in “Chapter Two” of this case study: KASP.

In the new 2014 edition, 58 Years to the Treason Trial, we worked with the partner school in Johannesburg Freedom Community College, as well as a new partner school in Polokwane, Kgagatlou Secondary School, to revise the publication in the classroom with learners and teachers. This process of working away from the original space of the Drill Hall has opened up new ways of programming. Keleketla! embraces nomadic, mobile and sparse programming around education and experiments.

A video archive is in the final stage of digitalization, opening opportunities for new ways of sharing through publications, presentations and performances. Keleketla!’s digital material allows for wider access and exchange, a route that opens opportunities for the conflation of the traditional and technological knowledge spaces.

_

1 The Joubert Park Project (JPP), a collective of artists working in Joubert Park, Johannesburg between 2000 and 2009, was concerned with public art in Johannesburg. It was led by Dorothee Kreutzfeldt, Joseph Gaylard and Bie Venter. Between 2004 and 2009, the JPP worked from the Drill Hall, negotiating public art projects on the site and surrounds. The JPP ceased programming in 2009, a year after Keleketla! established itself as a project interested in day-to-day programming. JPP offered support to Keleketla! in its early stages with its two members active in Keleketla!’s membership on a board level.

2 For a review.

3 For a collective review.

4 R30,000 South African Rand = .089 dollars (2,691 USD) .215 Reais (6,468 BRL)

5 The Kwaito family tree includes Bubblegum (1980s), Mbaqanga (1970s), Kwela (1950-1960s), and Marabi (1930-1950s).