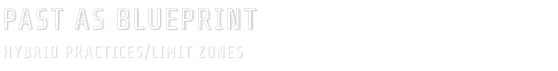

Richard Serra. Rio Rounds, exhibition by Richard Serra at Centro Municipal de Arte Hélio Oiticica, 1997-1998. Photo: Cesar Barreto.

A Minor Education, A Minor Art, A Minor Museum: The Study Groups Run by the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art at MAM-RJ

Mara Pereira

[…] we are no longer living at a time of prophets, but a time of activists.”1

Antonio Negri

Seventeen years after visiting the exhibition by Richard Serra held at Centro Municipal de Artes Hélio Oiticica (CMAHO), Rio de Janeiro in 1997 and 1998, I can see that some of his black monochrome drawings have actually leapt off the walls and into my working process as an educator and coordinator of education programs in museums and cultural centers. My response to that past viewing experience has amplified and imbued many moments ever since. Looking back, I can see that it was then that I first started to wonder about mediation, even if I wasn’t yet aware of it.

One enduring perception from my experience of the CMAHO exhibition spaces occupied by Serra’s black drawings is of a subtle yet striking interference that gave me the unsettling impression of movement, which wasn’t there but yet was there, even though I didn’t really know how.

The sensation I experienced is consistent with the artist’s interest in “structuring sculpturally a given context and thereby redefining it,” using drawing for this purpose.2 Serra is interested in creating tension in space and architecture, triggering a “disjunction in the architectural entity” so that, as he himself puts it, “the drawings bring formal and functional characteristics of the architecture to the viewer’s critical attention.”3

My drawings started to take on a place within the space of the wall. I did not want to accept architectural space as a limiting container. I wanted it to be understood as a site in which to establish and structure disjunctive, contradictory spaces.”4

What most interests me in Serra’s drawings is this structuring of “disjunctive, contradictory spaces”5 by making cuts that, he explains, have to be done in such a way as to destabilize the experience of the space, with drawings that “make the viewer aware of his body movement in a gallery or a museum space. They make him aware of the six-sidedness of a room.”6

Richard Serra. Rio Rounds, exhibition by Richard Serra at Centro Municipal de Arte Hélio Oiticica, 1997 to 1998. Photo: Cesar Barreto.

I would draw attention here to the subtlety of/in the monumentality, the circumstances in which the processes are hidden and revealed, almost invisible, minor, and also contradictory and destabilizing, highlighting the relationship between the body and its movement in specific spaces. I want to draw on this line of thought as I review some of my experiences as an educator and coordinator of actions and content with the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, active at the Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro (MAM-RJ) from October 2009 to April 2013.

Museums, Schools, Teachers: At the Service of What/whom?

Richard Serra stresses that the experience of a work is inseparable from the place it occupies. We could take this observation further to draw a link between site-specific art practices and education programs at museums, and even with the work of teachers in schools.

We could shift the site-specific concept to educational practices in museums and schools and still preserve the idea that interventions of this nature have the power to introduce tension to architecture, space, physical structures, and interpersonal relations.

Thinking specifically about the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, all the issues presented so far are relevant. The idea is not to talk about the project as a whole, because a single text could not possibly do it justice in view of the sheer number of actions taken and the profile of the team of educators, artists, and cultural producers who worked collectively and also developed individual research and initiatives, often without the need for the guidance of a coordinator of actions and content.

The Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art engaged in a number of programs such as: Exhibitions Conversations, Open Studio, Multisensory Encounters, Dialogues, and artistic participatory events called DouAções (neologism of Portuguese words doar = to give and ação = to act) and collaborative initiatives: Museum/School, Irradiations, International Seminars, and Joint Action (together with the museums curatorial department).

The propositions, some of which involved ad hoc actions and others of which were run continuously, focused on experimentation of an artistic/educational and poetic/critical nature, creating the opportunity for cross-fertilization between exhibitions, partner institutions and professionals, the MAM-RJ architecture designed by Affonso Eduardo Reidy, and the surrounding landscape, including the gardens designed by Roberto Burle Marx, Flamengo Park, Guanabara Bay, and the other buildings, extending out to include experiences in other parts of the city and state.

Throughout the whole process the project was conceived collaboratively with the participation of multiple agents, including students, family members, teachers, artists, researchers, curators, managers, and participants of educational, cultural, social, and health projects from Brazil and abroad, all of whom had some kind of interest in finding out about, experiencing or revisiting the parallels and links between museums and other institutions, education, art, and people’s multiple daily experiences in contemporary society. I could focus more on the programs that were produced more frequently, or that had more lasting impacts on the museum, or that had greater visibility or served a bigger audience. But instead I have decided to focus on two singular actions that were not spectacular in scope, and for this and other reasons did not have the kind of profile generally expected by managers of institutions or sponsors, who may be unfamiliar with projects that involve critical pedagogy and steer clear of today’s hackneyed education program formats. This lack of attention and interest has tended to confirm the ideas I have refined over the years about how education programs could work in cultural venues, especially in association with a minor way of being, as I intend to present in this text.

The actions I will focus on were part of the Museum/School initiative, geared towards forging collaborations and partnerships with educators from different areas with a view to finding and fostering common ground between schools and museums and bringing to light the potential that exists for poetic and critical experimental education.

In the second semester of 2012, the Nucleus developed a partnership with the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Secretary of Education (SME – RJ) in the elaboration of a project that proposed the participation of teachers in the following programs: Open Museum – Encounter with Educators; Study Groups: Relationships between Museums and Schools for the 21st century, and in the creation of a pilot project with the Municipal School Emílio Carlos. In addition, the Nucleus began an initial collaboration with the State Education Secretary for Rio de Janeio (SEEDUC – RJ) encouraging teachers to participate in the Study Groups and also engaging in encounters with teachers and administrators from the State Ethno-Racial Committee on education. In 2011 the Nucleus had established a partnership with teachers in collaboration with the state-wide initiative Projeto Autonomia (Autonomy Project).

The Museum/School initiative was subdivided into three areas: 1) Meetings with Educators: Open Museum; 2) Study Groups: Relationships between Museums and Schools for the 21st century; and 3) Connections: Art and Other Disciplines. The specific activities I will discuss in detail are two events held as part of the Study Groups component in different months of the same year, and one activity from Connections: Art and Other Disciplines.

The actions were structured and developed by Jessica Gogan and Luiz Guilherme Vergara, coordinators of the Experimental Nucleus for Education and Art of MAM-Rio, the educators Ana Chaves and Gleyce Heitor, and the producer Taisa Morena, with my collaboration as educator as well as with the two artists/educators Bernardo Zabalaga and Virgina Mota.

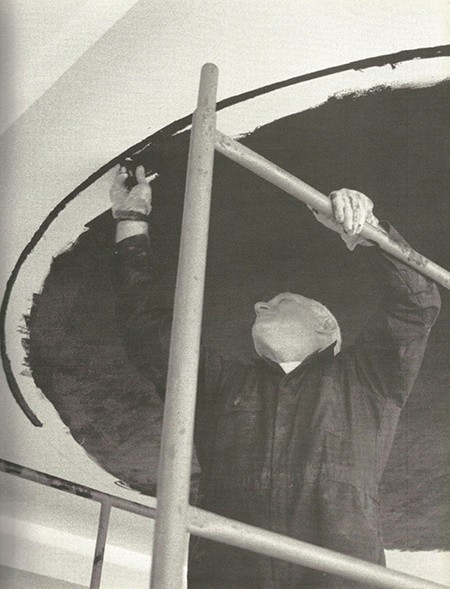

Study Group with Teachers. Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, September 2012. Photo: Taisa Moreno.

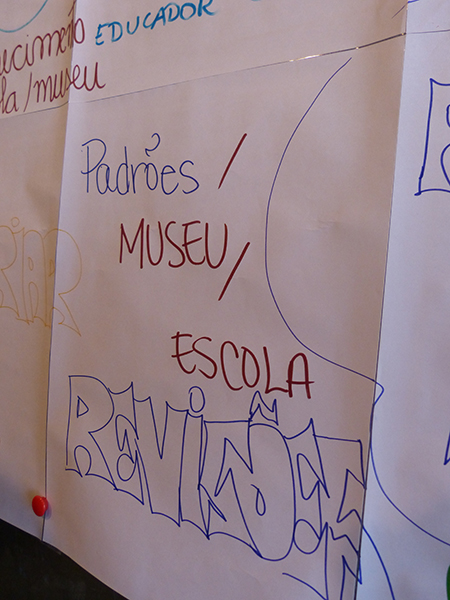

Study Group with Teachers. Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, September 2012. Photo: Taisa Moreno.

On September 20 and October 29, 2012, the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art held two study groups with teachers with the idea of analyzing and discussing the common ground, collaborations, and tensions between museums and schools by looking at different models for education and museums in the 21st century, how these two types of institutions interact, and what they mean in the public sphere. We were keen to reflect on and discuss the public role of art museums and cultural venues, and contemporary challenges both locally and globally, based on approaches that were feasible for teachers working in very diverse social realities: schools in high-risk areas of the city, prisons, the periphery of Rio de Janeiro (Baixada Fluminense), police/drug gang combat zones, and private schools.

As the idea was to create a long-term program, the first step was to map out all the agents involved – institutions, educators, students – and where they operated, then to devise action plans for fostering exchange, interaction, and collaborative learning through discussion forums. These could focus on developing classroom materials, strategies for fostering integration, and partnerships between museums and schools. There was a desire to effectively create a museum/school laboratory, where teachers could develop their knowledge through participation in study groups. Even though the specific nature and function of schools is already established, we were keen to consider some other questions: What would be the characteristics of a form of education that could emerge in or from a museum? What are the practices and discourses that legitimize us as educators? What challenges face the people working in education in contemporary times? And so the group was set up grounded in a mutual desire, both that of the educators from the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art and those with whom we wanted to interact with, to set aside space and time for reading, exchanging experiences, and acquiring new knowledge in order to enrich and empower our discourses and practices.7

In the first study group the focus was on the relationship between museums, schools and the city. It centered on one question: “Where do museums begin? Cities as territories for learning.” The 29 participants of this group worked at museums, cultural institutions, NGOs, and public and private schools. We broke out into three groups. Two of them read and discussed “Arte contemporânea e educação” (“Contemporary art and education”), a text by Celso Favaretto, from the Faculty of Education of the University of São Paulo, and the third focused on “Escola pública da arte x Escola de arte pública – irradiações e acolhimento” (Public school of art vs. public art school – irradiations and reception), by Luiz Guilherme Vergara, professor at the Institute of Arts at the Federal Fluminense University, who at the time was one of the general coordinators of the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art.

Twenty-one people took part in the second study group. Some were new and many were coming back for a second time. The subject was transdisciplinarity. In the morning, the group read and discussed “Currículo [entre] imagens e saberes” (Curriculum [between] images and knowledge) by Sílvio Gallo, professor at the Faculty of Education of Unicamp. In the afternoon, ideas about art practices and learning practices were developed based on a visit to exhibitions by Luiz Zerbini, Raul Mourão and Cabelo, identifying how their work interacted with the debate about transdisciplinarity and creating a diagram based on the concepts of tree and rhizome presented in the text. The texts read in both study groups prompted discussions about the paradigms that define education today, the restrictive, established models and concepts in the education system and learning processes at schools and museums.

Study Groups with Teachers. Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, September 2012. Photo: Taisa Moreno.

While Celso Favaretto’s text questions the desire for enlightenment, progress, and the stimulation of creativity, Sílvio Gallo’s text critiques the compartmentalization of knowledge in disciplines and puts forth the case for a more holistic approach, complementing reflections about and problematizing certain elements that may be taken for granted in a school curriculum, suggesting instead that knowledge and learning can take place in networks and in multiple, cross-disciplinary, non-hierarchical ways. In Luiz Guilherme Vergara’s text, which also contains mini-texts by the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art team, what is highlighted is the socio-cultural agency driven by artists and educators inside and outside museums, in the Irradiations program, and in the way the public is received and art production processes shared with “non-artists,” people from poor communities, participants of social and cultural projects, and school children.

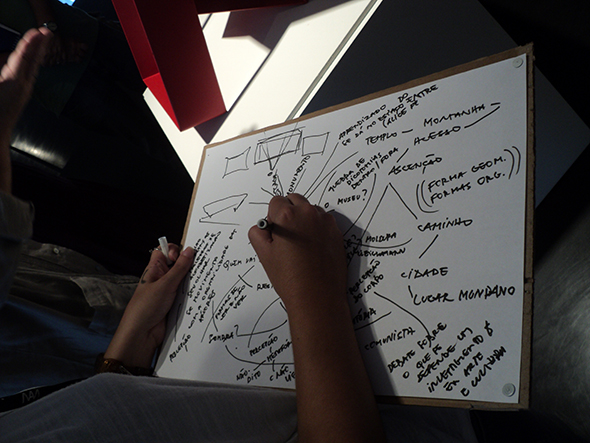

On March 16, 2013, an event called Connections: Art and Other Disciplines was held with a private school from Rio de Janeiro, Colégio Andrews. It was planned as the first of a series of collaborations between the school and the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, based on both institutions’ interest in working together, but sadly became a one-off encounter because the Nucleus was closed down just two months later. The participants included the school’s principal, education coordinator, education supervisor, art teachers, and coordinators of other subjects, including early childhood education and biology. Some different experiences from Brazil and abroad were presented, showing the different ways museums and schools can work together. The topic of transdisciplinarity was introduced, as were the working ideas behind the Museum/School initiative and certain topics the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art had investigated with groups and individuals during visits to the museum and in other activities that give rise to the questions and themes: where does the museum begin? art practices; body and identities; and modernities and contemporaneities. After this, the participants broke out into three groups to discuss the proposed topics in greater depth. They then visited an exhibition at MAM, Genealogias do contemporâneo (Genealogies of the Contemporary), where they further developed the ideas discussed in their respective groups.

The discussions about art practices and modernities and contemporaneities started by considering how these topics are covered in educational projects, classroom activities, and interactions with students at school. Questions such as fluidity, new technologies, relationship with time, and the multiplicity of simultaneous productions were raised, and some common ground between the issues prevalent in contemporary schools and contemporary art started to be identified.

Connections: Art and Other Disciplines. Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, March 2013. Photo: Taisa Moreno.

We talked about some of the issues in the passage from modern art to contemporary art, how the two terms are often mixed up inside and outside the art world, and how they interrelate with sociocultural, political, and educational issues. We then visited the Genealogias do contemporâneo exhibition. The topics raised again confirmed how hard it is to discuss contemporary art at many schools. There are problems in how to address and experience the subject, and art as a school subject and art teachers themselves are often seen as superfluous, which in turn contributes to the emerging politicization of art teachers at schools.

The school’s education coordinator and supervisor found that the subjects raised by the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art in its work at MAM-RJ regarding the themes – where do museums begin? modernities and contemporaneities, body and identity, and art practices - resonated directly with what they experienced at school. They said they could serve as inspiration for all their projects before they even found out that these subjects had actually been selected as a result of interactions over the years with teachers and students on visits and in other activities organized by the Nucleus. These core topics were not imposed or selected unilaterally; they were formulated by observing the interests, dialogic processes, and constructive knowledge building processes with educators from the museums and from schools, and thinking about what the museum can elucidate through its architecture, its events, and its sociocultural outreach activities.

The experience of the two study groups with teachers from different institutions and backgrounds and the encounter with teachers from Colégio Andrews reinforced my belief that investing in the creation of continuous study programs with educators from museums, schools, and other institutions, not just from the realm of the arts, but across the board, bringing together and transforming different fields of knowledge, engaging with school principals and education supervisors and coordinators from all these different kinds of institutions, is increasingly necessary, but is perhaps, ironically, the last thing that springs to mind when one thinks of an education program. I am not referring to the qualifications of the teachers directly involved in organizing their classes, the declared operationalization of the immediate multiplication of audience numbers, which does not cease to be a possibility, but I am defending study for study’s sake, beyond the established educational norms, making room for more in-depth investigations, reading circles, reflections about case studies, and research.

I am referring to micro, focused, almost invisible actions with no mass communication strategy (although just because they involve a limited public does not mean they are exclusive), and this brings me back to my experience of Richard Serra’s drawings at CMAHO, and the impression they gave me of movement, even though it wasn’t there, yet it was. Discreet, powerful, subversive.

It is important to enable the occupation and movement of bodies, not just around architectural spaces, but in the institutional sphere, destabilizing received knowledge in institutions; the experience of the space where visitors are expected to go and see exhibitions and learn about their content to pass on to their students or take them to the museum; there should be more room for critical debate about education, culture, institutions, and society.

In her testimony about her participation in the study groups at MAM-RJ, a professor from the UFF faculty of education, Maria Teresa Esteban, said that although it was a ‘minor’ initiative, it brought up some fundamental issues to which, in her view (and also in mine), there are no clear, immediate or definitive answers. She reflected on the question, “Where do museums begin? Or schools?”

In the absence of an answer to close the circle, questions that matter will always come round again, reappear, evoke experiences in people’s eyes, gestures, and limited, often faltering words, which open up dialogue and the chance of understanding that it’s not so important to know where things begin, but to know that the experience of going further in multiple processes pursued at encounters with others is possible. Where do schools encounter the world in which their meanings are constituted? What are the formative experiences for schools, in schools, with schools, about schools? That project gave us a chance for reflection. The smaller proposals, the less organized routes, the intensity of art as a practice, seem to me to be vital for the development of teachers for schools that don’t want merely to lay down boundaries, but would rather be spaces for education as a dialogical, liberating experience.”8

Connections: Art and Other Disciplines. Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, March 2013. Photo: Taisa Moreno.

Connections: Art and Other Disciplines. Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, March 2013. Photo: Taisa Moreno.

I believe it is crucial for learning processes to be proposed that are continuous and conceived in conjunction with students, and for education programs to serve as potential territories for research and debate, without posing or expecting to have all the answers, recognizing that education takes place in life, inside and outside museums, schools, social and cultural projects, and institutions as a whole. We must be wary of focusing on attracting and receiving groups, building visitor numbers, and merely getting the word out about a collection or planned activities of the kind that are generally propagated as the main goal of education programs, and ask ourselves: Why are most education programs the way they are? Why do the models change so little? Why do they always seem to be based on the same things, even when they are varied? What legitimizes an education program? Who and what do these models serve?

It is important to provide settings that encourage the production and reception of different ideas inside different places, different educational and artistic architectures, program concepts, in interactions between the people involved, in the arid terrain of education, creating and identifying tensions, with those who form and those who seek to deform these spaces, and, like Richard Serra, taking up positions inside and outside these walls – I would even say inside and outside the pillars that sustain them.

Between Prophesying and Activism at Museums and Schools

Richard Serra’s site specific drawings were an intentional choice for the introduction to this text, as they can serve as a metaphor for what is minor, in much the same way that the work of Kafka is described as minor literature in some writings by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. They argue that “a minor literature does not come from a minor language; rather, it is what a minority constructs within a major language.” It is a subversion of language itself, which is its own “vehicle of disaggregation.”9

In social operational terms, I am not sure whether Richard Serra is the best reference, but the idea of making an association between his work, specifically his black drawings, and the meaning of minor comes from my realization of the subtle provocation they make; the way they interfere in the spatial macrostructure, drawing a fine line between the visible and invisible, the sensible and the unsayable. What Serra is capable of tracing is in the body of the work, in the architectural body that harbors the works, and above all in the body of those who see and move around in front of them. It is the destabilization and resistance of bodies in space. A distancing between merely formal experiences and broader perceptions, decisions, and positions. It is in this perspective that I believe what could be considered as minor resides. In his book, Deleuze & a Educação, Sílvio Gallo writes:

Minor education is an act of rebellion and resistance. Rebellion against instated flows, resistance against imposed policies; classrooms as trenches, as the mouse hole, the dog’s den. Classrooms as spaces where we can design our strategies, focus our activism, produce a present and a future that is smaller or greater than any educational policy. Minor education is an act of individuation and activism. If major education is produced in macropolicies, government offices, expressed in documents, then minor education lies in the realm of micropolicies, the classroom, expressed in each person’s daily actions.”10

If Richard Serra’s drawings reaffirm the nature of spaces – their mathematical, architectural configuration – they also seem to question them. Indeed, they also question the viewer about what is not evident but should be. Which perhaps for some continues to be the case.

If we are not aware of space, how can we perceive any tensions constituted in it? In other words, if an interference lays bare the potency of the microinvisible, what should we do now with the unsettled feeling we get when it is revealed?

The almost invisible, the minor, is what is done inside the macro. It is capable of unseating it, and can take the form of rebellion and resistance, individuation and activism, subversion and micropolitics.

Minor can be an artist’s output, an aesthetic experience, a museum, an exhibition, education itself – in a school or anywhere else.

Mirroring Sílvio Gallo, who transposes the meaning of minor literature to minor education, giving minor a sense of activism and entrenchment in the classroom, I would like to transpose this practice of activism and entrenchment to the museum, especially education programs in art museums, based on my reflections about the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, in a bid to understand to what extent the actions we took were in fact minor. In his text, Gallo complements the idea of minor education with the figures of the prophet teacher and the activist teacher, developed by Antonio Negri in Exílio: seguido de valor e afeto. Gallo goes on to explain:

(…) today, what matters more than foretelling the future seems to be producing the present with each day that passes in order to make way for the future. If we shift this idea to the field of education, it is not hard to think of a prophet-teacher, who, from the height of his/her wisdom, tells everyone else what they should do. But along with the prophet-teacher, today we should also be driven as a kind of activist-teacher, who, in his/her own desert, his/her own third world, takes transformational actions however small they may be.”11

For Gallo, drawing on Deleuze and Guattari, a prophet-teacher is a legislator that envisions the new world and builds laws, plans, and guidelines to make it happen. Meanwhile, the activist-teacher is in the classroom, operating on the level of daily micro-relationships, building a world within the world, digging trenches of desire.

Perhaps the prophet is the one who foretells from an individual point of view. But the activist always has collective action; the activist’s action is never isolated (…). If the prophet-teacher is the one that goes out alone to rouse the masses, the activist-teacher is the one that acts collectively to reach out to each and every individual.”12

We could add that the activist-teacher is the one that also lets him/herself be touched. They are the ones that prompt, instigate new agencies, and are involved by them, but also by other agencies that others have instigated. According to Negri, activists are the ones that know how to “identify new forms of exploitation and suffering, and to organize from these forms processes of liberation, precisely because they take part actively in all this.”13

When these relationships are transposed to an art museum, I would say that managers, curators, and sponsors are the ones that are closest to prophetizing, if we consider the scale Sílvio Gallo is referring to. Likewise, many education program coordination teams, particularly the larger ones, keep a distance between the plans and concepts and their applications in relation to others, while activist-educators operate on the daily basis of the museum-classroom.

While not wishing to adopt a divisive discourse but also going beyond Gallo’s position, it seems clear to me that we should recognize that activism can exist at the managerial and curatorial level, in any kind of collective action, and that educators can be anything but activists and more like individualists, leading the masses from the height of their position as prophets. It seems that if we are to transfer the concept of the prophet-teacher and activist-teacher from the school to the museum, we should fit managers, curators, and sponsors into the category of teacher.

Looking at education in its broadest sense, we cannot deny that the administration of knowledge and funding decisions are also education, imbued with stated or unstated political positions that have to do not just with what is related directly to education programs, but also encompass cultural institutions as a whole, everything they do. Other sectors also engender ways of thinking and doing education, whether humanitarianly or capitalistically.

Likewise, education programs in museums, with their different discourses, practices, and political stances, can take on the role of another “machine for control, machine for subjectivation, for the production of individuals in series,” but they can also be founts of resistance, subversion, activism.14 And with today’s abounding contradictions, they can be all this all at once.

Even though I may see a stronger tendency one way or another, I can clearly see the contradictions that are inevitably faced when projects of this kind are devised, whether by educators or manager-educators. There are negotiations, uncertainties, and demands in the terrain between the prophet and the activist that can drive them from one path or from another, empowering the projects but also triggering conflict and strife.

When I look at the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art and many other art education projects, I am not sure if we were more prophets or more activists. I don’t think that can be answered.

Since the late 1990s I have observed the rising tide of education programs in cultural institutions and visual arts biennials, and it is clear how the biggest institutions are almost always the point of reference, with their surplus of projects, audience, and staff and their need to strike a balance between educational interests and market interests, between mediating with the public and mediating with art institutions; mediation engendered by educators, but also by curators, managers, and administrators. And sometimes, amidst the failures and successes of the mediations, trying to understand what they each mean.

In “Why mediate art?” Maria Lind foregrounds and critiques what she sees as an “excess of didacticism and simultaneously a renewed need for mediation” in educational actions at cultural institutions, but also in curatorial practices that are so obvious that there is often nothing educational about them, but just “selecting, installing, and in other ways contextualizing work.”15

The curator reflects on models of curatorship, especially at MoMA, where, in the 1930s, pedagogy was an inherent part of the curatorial approach, and in 1937 a separate education department was set up. She also discusses the idea of consumer spectatorship, constructivist spectatorship, and the intervention of marketing in institutions and education programs like a dating service “needed to put the right people and ‘things’ in touch with each other.”16 Maria Lind argues that mediation can be far more than this. “Mediation appears to provide room for less didacticism, less schooling and persuasion, and more active engagement that does not have to be self-expressive or compensatory.”17

This “active engagement” Lind refers to is in experimental art and curatorship, which have the power to “formulate new questions and create new stories,” distancing themselves from the mainstream circuit. She goes on to state that the mainstream is not sympathetic to ‘side’-streams, and vice versa. As in the study groups organized by the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, the aim is not to present models, set recipes or practices to be copied in the classroom based on the museum’s perspective, from a position of superiority, but together to build an open space for reflection and debate, a forum for active listening in different directions without one side being better than another, without one being seen as expressing an absolute truth.

Study Groups with Teachers. Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, October 2012. Photo: Taisa Moreno.

I believe in the power of human encounters, and that it is possible to think of education as mediation and not as one thing or another, but to step away from the excesses of didacticism and persuasion to which Lind refers. One thing that does interest me greatly is Lind’s mention, in the conclusion of her text, of the ideas of Irit Rogoff, professor at the Department of Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London, who holds that “reaching new audiences is less relevant than changing the terms in which we talk about how we together produce a public or semi-public space thanks to, with, and around art, curated projects, institutions, and beyond.”18 And also, education programs.

I recognize that in view of the different limitations that impinge on Brazilian people’s access to public cultural and educational programs, it is hard not to obey the command to “reach new audiences.” But I must also recognize that that alone is not enough.

Further references

Celso Favaretto. “Arte contemporânea e educação”. In: Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, nº 53, 2010, pp. 225-235.

Sílvio Gallo. “Currículo (entre) imagens e saberes”. Available at http://www.grupodec.net.br/ebooks/GalloEntreImagenseSaberes.pdf.

Luiz Guilherme Vergara. “Escola pública da arte x Escola de arte pública.” In: Concinnitas: arte, cultura e pensamento. Revista do Instituto de Artes da UERJ. Ano 12, número 18, June, 2011.

_

1 Antonio Negri in Sílvio Gallo. Deleuze & a Educação. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2008, p.59.

2 Vanda Klabin ed. Richard Serra. Rio de Janeiro: Centro de Arte Hélio Oiticica, 1997, p.67.

3 Ibid, p. 70

4 Ibid, p. 67

5 Ibid, p. 68

6 Ibid, p. 69-70

7 Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art, 2012. Available at https://nucleoexperimental.wordpress.com. Accessed April 2014.

8 Statement given by Maria Teresa Esteban, professor at the UFF Faculty of Education, by email on April 6, 2015.

9 Gallo, op cit, p. 62.

10 Ibid. p.64-65.

11 Ibid, p. 59-60.

12 Ibid, p.61.

13 Negri in Gallo. op cit, p.60.

14 Ibid, p. 65

15 Maria Lind. “Por que mediar a arte?” In: Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy and Hoff, Mônica Hoff eds. A nuvem: uma antologia para professores, mediadores, aficionados da 9ª Bienal do Mercosul. Porto Alegre: Fundação Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul, 2013, p.183.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid, p. 188.