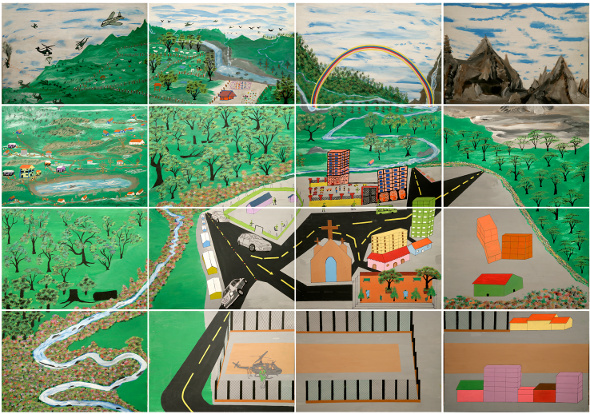

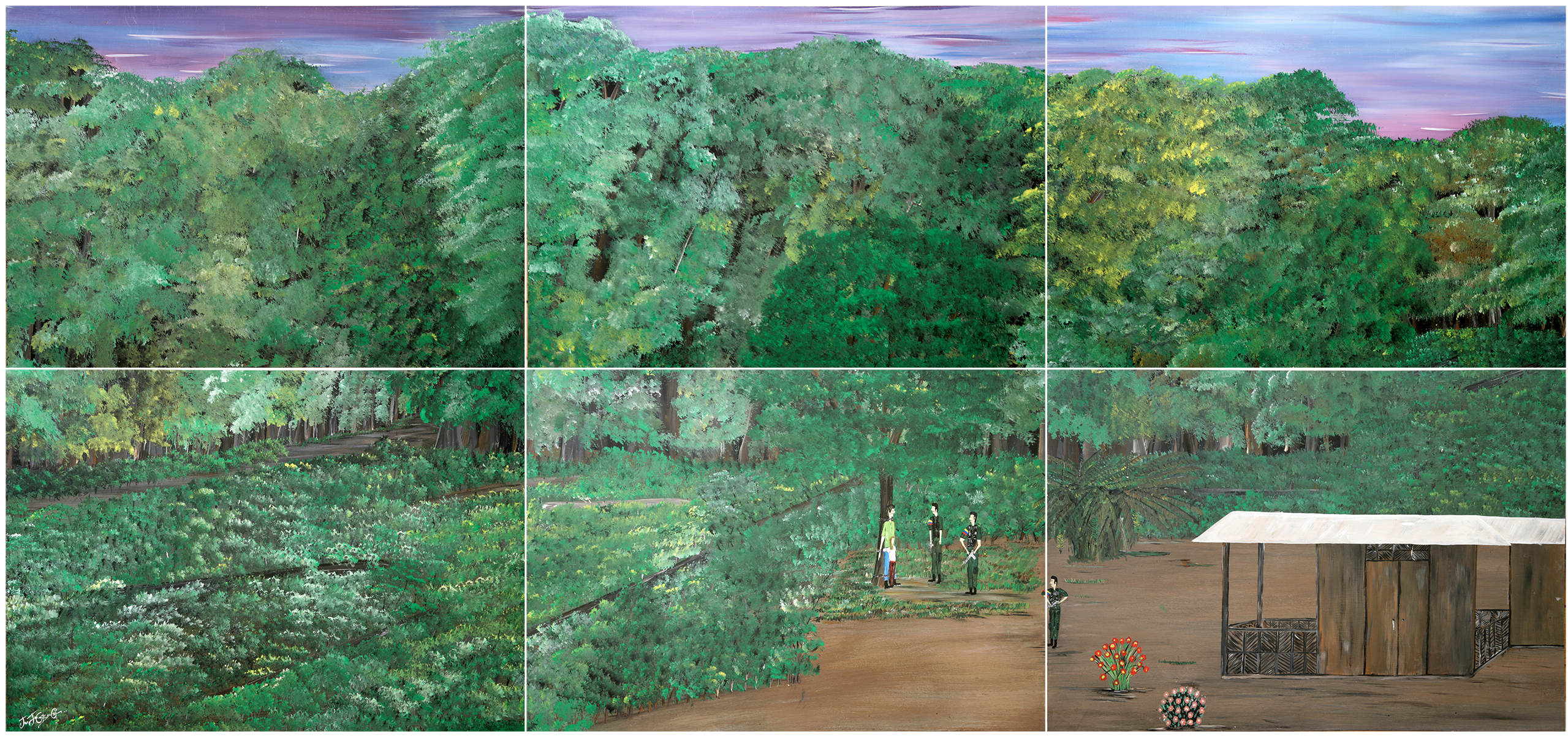

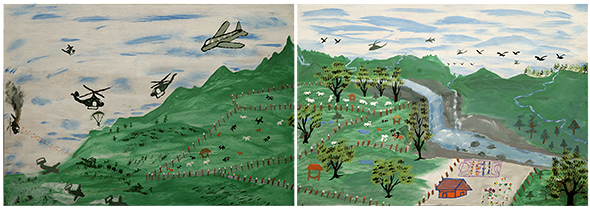

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown author. Vinyl paint on MDF. 140 x 200 cm, 2007.

Juan Manuel Echavarría: Multiple Voice Biographies in The War We Have Not Seen

Roberta Condeixa

I am going to create what happened to me. Only because living isn’t tellable. Living isn’t livable. I shall have to create upon life. And without lying. Yes to creation, no to lying. Creation isn’t imagination, it’s running the huge risk of coming face to face with reality.”

Clarice Lispector1

When an encounter means losing oneself

Holding the catalogue of the project La guerra que no hemos visto un proyecto de memória histórica (The war we have not seen: a historical memory project), 2007-2009, by Columbian artist Juan Manuel Echavarría, during a meeting at Casa Daros in 2011, the unknown and the unnamable affected me, as if I was at a zero point. At first glance, the images of the paintings presented lush jungle greens, then, suddenly they burst forth with violent brutal human acts, as if they were disconnected from everything.

The meeting with the artist was to develop a project for the inaugural program of Casa Daros in 2013.2 With me were the Art and Education director and manager of Casa Daros, respectively, Eugenio Valdés Figueroa and Bia Jabor. Some ideas were born, many with the focus of generating a dialogue via the artist’s practice about the complexity of violence and war. Echavarría reflected on the Colombian drug war and we on the “private” war plaguing Rio de Janeiro and how there were similar characteristics between both wars.3

Various themes pervasively cross Echavarria’s project: the tragic history of his country; artistic practice as a powerful place of speech; language as a mirror; war and its mutant nature; tragedy as discourse; the limits of the art circuit for such projects.

Juan Manuel Echavarría – being an artist in a country at war

Echavarria was born in Medellín, Colombia, in 1947, one year after the beginning of a period known as La Violencia, when diverse bloody civil wars marked the history of Colombia.4 Like most contemporary artists of his country, not only their life, but also, their artwork has been circumscribed by social and national political events. Many of these conflicts still persist. The Colombian war is predominantly located in the countryside, but invariably reaches the entire country.

While still a child, Juan Manuel went to study in the United States, a traditional practice for wealthy families in Latin America seen as a means of perpetuating their elite state. Experiencing childhood and adolescence far from his country generated in the artist a sense of having lost part of his origins, his identity. Echavarría is the son of the “historic shame that we have of ourselves.”5 His work, as recompense and principle, strives to make memory, oral literature and Colombian tradition part of critical discourse.

Tracing a dialogue between culture and war, Juan Manuel engages with relationships of resistance in collective spaces (communities) and among individuals through the use of a poetic language. His works expose the limits of humanity at war, as much through voice as through markings and silences.

Writing was for many years an opportunity to seek an identity. His two novels, La gran Catarata (1981), and Moros en la Costa (1991) assessed by the artist himself as unreadable, were part exercises and part discoveries of forgotten Spanish words. But on the eve of his 50th birthday, Echavarría dared to engage with another language to express himself, and the image began to take the place of the word.

In the 1990s, feeling “in a state of blindness,” the artist began his research with photography: “My photography has led me to want to enter more in my country and to face the present … I focused on the social problems of Colombia and this led me towards a much more conscious path, one where there is no return to an art in which the fantasy of mythical times prevails.”6

Embarking on travel, encountering and discovering communities still at war in Colombian territory, the artist recorded image metaphors of social realities, as well as traces and indexes of people who are “desplazados (displaced)” by violence.7

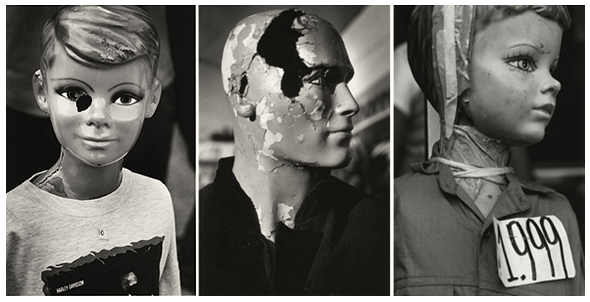

Portraits, 1996. 35.4 x 27.9 cm. Silver gelatin prints. Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zurich.

The work Retratos (Portraits), 1996, evolved from observing the street life of Bogota, where he found mannequins completely destroyed still displaying clothes. Echavarría links us directly to the “suffering” that the war impinges on peasants, urban residents, and ordinary citizens in all its physical mutilation but mostly the symbolic destruction that violence causes.

Orquis Negrilensis. 50.5 x 40.7 cm, 1997. From the series Corte de Florero. Silver gelatin print. Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zurich.

Many of his later works would deal with metaphors that show the tragedy and barbarity of war, for example works such as Corte de Florero, 1999, which exposes the tragic side of carnage elaborated as a scientific classification of flora species. The unpredictable clash of bones with flowers (latent life) makes direct reference to the mutilation of corpses in war through cuts, as documented in the book by anthropologist Maria Victoria Uribe.8

It is with the works created in the first decade of the 21st century that voices of Colombian citizens–both singers/songs resisting war (Bocas de Ceniza, 2003-2004) and the ex-guerrila/authors9 of the war from the project The war we have not seen that would prove to be the peak of a discursive turn, when the artist “opened the walls of his studio.” It is in this decade when Echavarría’s practice becomes more one of being an editor, a collector of enunciations, bringing together and building a discourse of multiple voices.10

What interests me most today is what I’m seeing and discovering in the Colombian countryside, in the geography of war, and to show in the cities that are so far removed from the war.”11

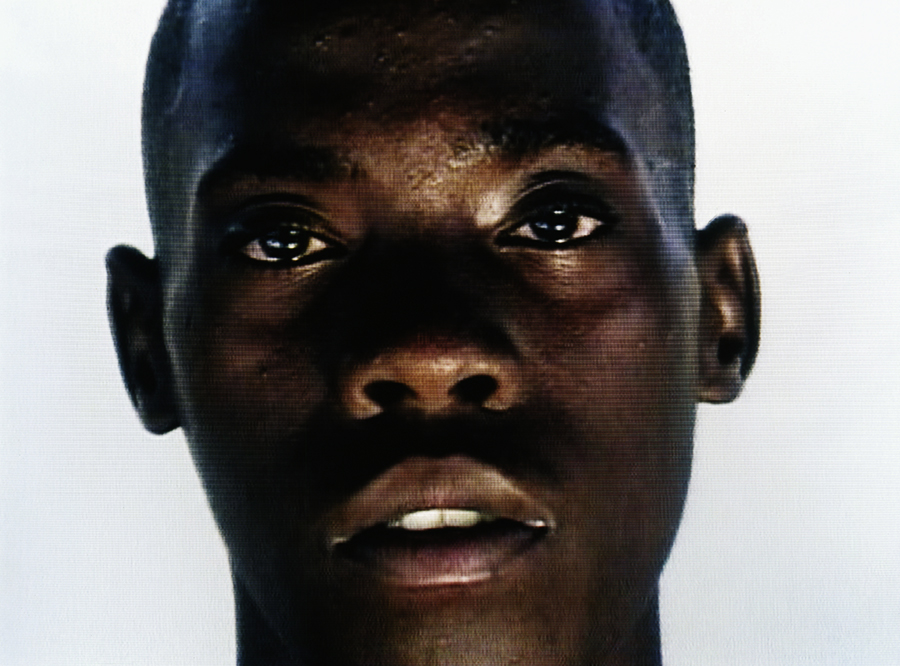

Luzmila Palacio. Bocas de Ceniza, 2003–2004. Single channel video, 18:50 min, color, sound. Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zurich.

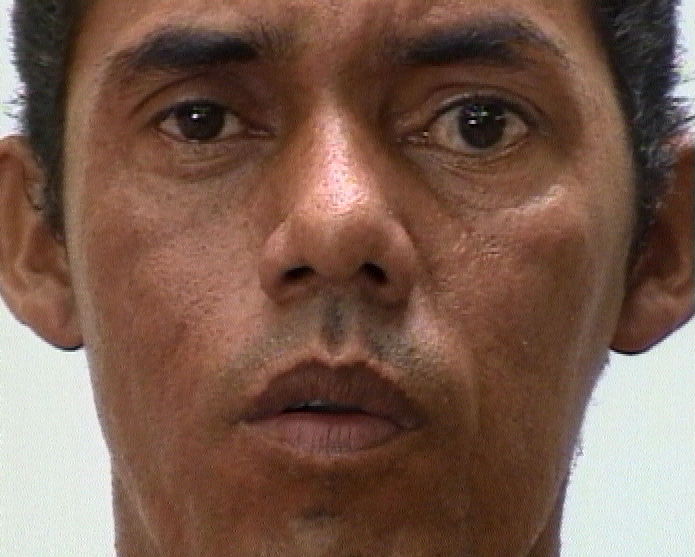

Noel Gutiérrez | Nascer Hernández. Bocas de Ceniza, 2003–2004. Single channel video, 18:50 min, color, sound. Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zurich.

Using the medium of voice Bocas de Ceniza marked a paradigm shift for the artist and his understanding of what it meant to be a creator. The songs of various singers recorded by Juan Manuel in diverse regions of Colombia poetically exalt resistance in shots where the eyes of the singers point us beyond the visible, provoking the overflow of social pains and joys in sound rituals that invade us and engage our intimacy and complicity.

Bocas de Ceniza is a key work in Echavarría’s career, and it is fundamental to understanding the project, The war we have not seen, which similarly uses polyphony and language as poetic exercise, as points of departure, to create a body of multiple voices. If in Bocas de Ceniza the artist records an existing protest in The war we have not seen he is the proposer, acting not just as an editor, but also as the generator of a polyphony that, paradoxically, was born from an historic silence of inoperative social voices but that now come into play in the work of art, a woven fabric reverberating in the contact zone between reality and imagination.

The War We Have Not Seen – A Historical Memory Project

A proposal of the artist Juan Manuel Echavarria

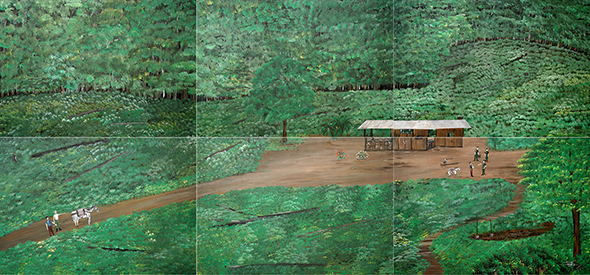

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Vinyl paint on MDF, 70 x 300 cm, 2009.

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Vinyl paint on MDF, 70 x 300 cm, 2009.

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Vinly paint on MDF, 70 x 300 cm, 2009.

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Vinly paint on MDF, 70 x 300 cm, 2009.

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Vinyl paint on MDF, 100 x 175 cm, 2009.

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Vinyl paint on MDF, 100 x 175 cm, 2009.

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Vinyl paint on MDF, 100 x 140 cm. Circa 2007.

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Vinyl paint on MDF, 100 x 140 cm. Circa 2007.

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Vinyl paint on MDF, 140 x 100cm, 2008.

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Vinyl paint on MDF, 105 x 100cm, 2007.

The project The war we have not seen a project of historical memory (hereafter La guerra…) involved a total of 80 people (women and men) including former infantry soldiers, combatants and deserters of the Colombian war, guerrillas (FARC), and dispensed paramilitaries as a result of the “Justice and Peace” law.12 They were invited by Echavarría to recount their stories in painting workshops between 2007-2009, with the aim of motivating the telling of the experiences of those in the midst of the drug wars in diverse geographic areas of Colombia.

Of the 420 works that resulted from these workshops, 90 were selected by curator Ana Tiscornia Uruguayan for a major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Bogotá, Colombia, in 2009 and these collectively make up the book La guerra que no hemos vistos – Un proyecto of historical memory (The war we have not seen – a project of historical memory).

In 2012 I visited the collection of Echavarría’s Puntos de Encuentro Fundación (Meeting Points Foundation) in Bogotá, to interview the artist and learn about the project La guerra in order to develop a project for 2013 at Casa Daros under the curatorship of Art and Education director Eugenio Valdés Figueroa and manager Bia Jabor.13 It fell to me to conduct the local research, plan and subsequently realize the program series forums Unbury and Talk.

I got to know how the paintings were stored, as they would be cared for by a museum with excellent quality archival storage; I interviewed Juan Manuel Echavarría and the participant-author Jhon Jairo Camacho, who described his experience in the war. I saw the process of how some of the paintings were made, as Noel Gutierrez and Fernando Grizales, who conceived and conducted workshops with Juan Manuel, meticulously took each painting out of storage to show me. (The images are formed by varying rectangles of Eucatex.) These opportunities enabled me to gain an expanded understanding of the project and, in turn, stimulated the proposal of making listening a priority for the series of forums we were planning on the violence experienced daily in Rio de Janeiro that would accompany the exhibition of Echavarría’s project.

The artist as a listener: The forum as a dialogue between wars, protests and art

In May 2013, a small exhibition comprising a selection of 11 paintings from the project La guerra… opened at Casa Daros, shown for the first time in Brazil, and accompanied by audio interviews with authors. Part of Echavarría’s residency at Daros was developed with the series of forums Unbury and Talk in mind. In these forums, after Echavarría shared his process, we created an arena of listening, so that new voices could express the experience of violence as a result of the “private” war experienced in our daily lives in Rio de Janeiro.14

Our proposal was to invite groups or projects in which art and collectivity would generate humanized and critical responses to a situation that mainly affects black and poor populations. The starting point was the voices of the guerrillas from La guerra… as mirrors for new voices.

We selected six groups to meet Echavarría during the exhibition. A sharing dynamic was created in the center of the exhibition intended to exchange projects and actions, provoke often silenced voices, trigger new discourses and authors who make use of different devices, mainly through art, in areas and spaces of the city where the right of access to cultural resources is scarce. They were:

Teatro do Oprimido (Theater of the Oppressed) of Maré that use the theatrical method of Augusto Boal that proposes real experience as the theatrical scenario;

The NGO Observatório de Favelas (Favelas Observatory), also from Maré whose program Imagens do Povo (People’s Images) uses photographic techniques focused on social issues, recording the daily life of favelas with a critical eye;

Cia Completa Mente Solta (Completely Free Mind Company), created in 2006 by the actor Márcio Januário, as a project of Art Education in the André Maurois State College, which offers young people an educational alternative to the classroom, stimulating reading, research, writing, and creativity through discussion of current or historical themes, which are then transformed into theatrical sketches, photos, text, music, or workshop discussions;

The NGO AMAR (Love) of Vidigal, a Women’s Association that promotes the empowerment of women in the community through working with diverse professionals and the use of psychoanalysis;

The State Commission of Truth of Rio de Janeiro, which aims to monitor and support the National Truth Commission in the examination and clarification of human rights violations committed during the military dictatorship, to affect the right to memory and historical truth.

In these forums Echavarría positioned himself as a listener, sharing the Colombian war through each of the paintings. What was really at issue was to understand human beings in states of violence, their reactions, their strengths and their state of reinvention of self and of becoming. These encounters created a territory, an opening up to the discourses of desiring subjects to the possibility of a becoming.

Nobody has ever lived without daydreams, but it is a question of knowing them deeper and deeper and in this way keeping them trained unerringly, usefully, on what is right.”

Ernst Bloch15

Each group was asked a question about their personal experience with violence, with education, with community, and how each one, and the group as a whole had lived through subversions and incarnations of speech. I can say that we operated in the anguish of facing life and against the “machinations of fear.”16

On the eve of the Forum with the group Observatório de Favelas – Imagens de Povo, the Maré favela was taken over by police, resulting in fatalities. In conversation with the people at the NGO via Facebook, the reports were ones of war. Police abuse is known to be standard practice in favela communities. Even in the homes of residents, human rights violations are common practices of the state. We thought about canceling the event that, planned for the next day, now seemed an affront, but collectively we understood that this is exactly why we should talk.

Coincidentally – or a reverberation of crisis points – the month in which the exhibition was inaugurated marked the beginning of June 2013 Brazilian street protests. First, announcing dissatisfaction with public transport, energized by the activist movement of Passe Livre (Free Fare), protests mushroomed across the country, especially after heavy police repression. The country freed its voice. Silent discontent appeared in the streets as an audible collective body.

The encounters with Echavarría were also open to public participation. The exhibition as medium enabled multiple voices of the hidden war lived daily in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro to be heard, ones that are not present in mainstream news media, where there isn’t even consensus of the war’s existence. In compensation, the Colombian jungle war, one of the most violent in the world, was revealed by reports and testimonials from those who lived through it.

Columbia, our frontier of stereotypes

A war, an image, an art of resistance

As art critic Miguel Gonzales has pointed out, Columbia is a country whose contemporaneity is born not via the rupture of languages or the superposition of temporalities, nor by economic hegemony, but rather by a new historical period singled out by civil war.

In reality the event that initiates contemporary Colombia occurred on April 9th, 1948, when an insurgent populace attacked the center of the capital city assaulting, burning and destructing buildings and means of transportation. El Bogotazo,17 as it was called, was a response to the murder of the movement’s leader and main opposition to the government, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán.”18

Colombia, Brazil and other Latin American countries cannot enrich their interpretations and research in art without first looking to their own particular stories of civil wars, dictatorships and liberation struggles, where there exists a latent context of the repression of speech. What potentialities or symptoms do these social equations provoke or bring forth in art?

In Colombia, the war against oligarchs historically headed for a drug war. Unrest began with the desires for revolution that also surfaced in various countries in Latin America as a result of the Cuban Revolution, and ended up turning into the civil war that continues today.

The consequence of the death of the leader Gaitán, associated with anti-communist repressions imposed by the United States in the 1960s, launched the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a group that opposed the alliance between liberals and conservatives. At the time, the guerrillas consisted of communists that after the radicalization of peasant guerrillas, fled into the jungle and mountainous regions.

FARC is one, among many, guerrilla and Marxist-Leninist revolutions to emerge in Latin America at the time, such as the Araguaia in Brazil, all of whom were inspired by Cuban revolution as a great example. These “wars” were mostly fought internally, but also against radical foreign threats, such as the United States and their financing of dictatorships in Latin America.

FARC became more and more controversial because they were backed by the drug market. They are called a terrorist organization by the Colombian state itself, and by the European Union and are considered an insurgent force by countries like Cuba and Brazil. FARC are also a major supplier of drugs to the North American market, engaging heavy involvement of foreign capital in their network.

According to the text published in the magazine Caros Amigos (Dear Friends) in 2011, Colombia has an army with the same amount of men and women of the Armed Forces of Brazil, a country with four times the population.19

The ignorance of most Brazilians regarding the social and political history of Colombia, a country that we border, can be seen as fundamentally political. Blindness perpetuated among Latin American countries with regards to each other was implanted as part of the conceptual “chips” of colonization. In the case of Brazil this is even more serious, as we are divided not only by a radical cultural imposition that leads us to take our cue from Europe and the United States, but also by language.

The annexing of land for colonization not only affected us economically and politically, but it also impacted the power of our inner voice. That voice, in addition to individual and collective history, is reflected in the project La guerra… As the curator José Roca suggests: “The losses derived from Eurocentric gaze (…) masked for centuries a proper understanding of local reality.”20

A private speech: The War We Have Not Seen – A Historical Memory Project (La guerra…)

La guerra… reveals how artistic expressions can be deployed as speeches of resistance and a means to reinvent a given reality. The project affirms the belief in art as a trigger for a living language, one which is constructed by potent states that express themselves as enunciations for life through poetic language, which, in the words of Suely Rolnik, is directly related to what is essential to us: “the poetic exercise is completely essential because it is exactly this recreation of thought which can occur as much in a work of art as in existence (…) the poetic is a policy of thought production to produce reality.”21

La guerra… makes visible how subjects relate externally and internally when they inhabit language, how they use their bodies to face up to the states of life, in turn metaphorically exposing our own bodies. As Eduardo Galeano proclaimed, our voice brings up “the ghosts of all the strangled or betrayed revolutions throughout Latin America’s tortured history, they emerge in new experiences, as well as present times, pervaded and engendered by the contradictions of the past.”22

Juan Manuel Echavarria’s project La guerra… brings us face to face with these social complexities and with the social within art, or even contrarily, exposes the complexity of art in contact with its (institutional) boundaries.

When the unknown is presented in images

Let us return to the paintings

To be is to be beyond the human. To be a human being doesn’t do it, to be human has been a constraint. The unknown awaits us, but I sense that that unknown is a totalization and will be the true humanization we long for. Am I speaking of death? No, of life. It isn’t a state of felicity, it is a state of contact.”

Clarice Lispector23

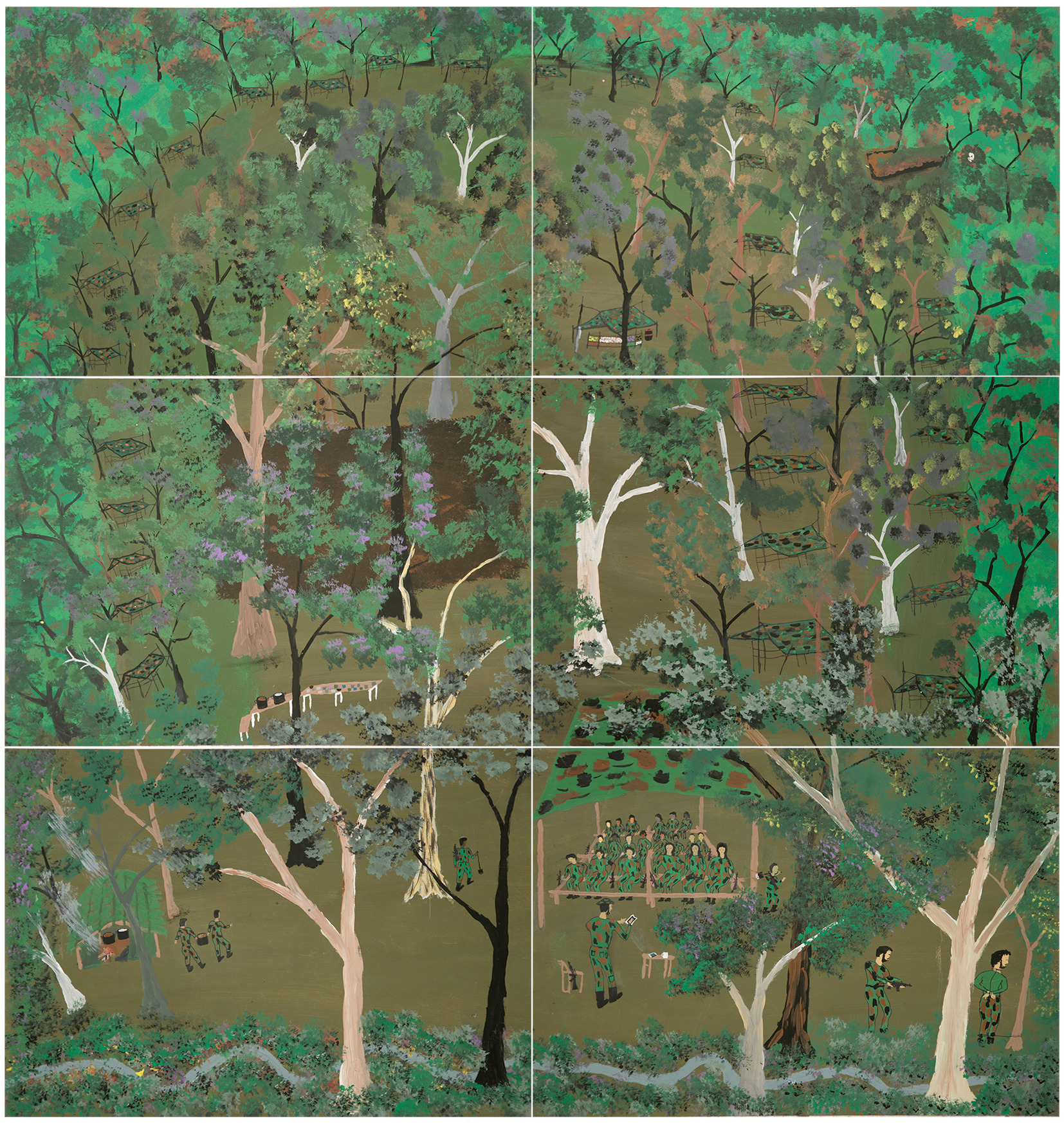

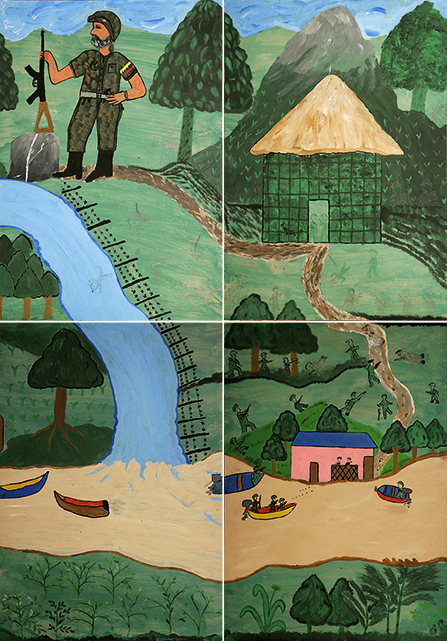

The naive nature of the paintings, the result of those who do not have any training or drawing skills–many are illiterate–offer unique foreground/background perspectives. Some paintings depict grand landscapes and aerial views. Others, in their foreground, highlight the narrated act; sometimes man is greater than nature, in others, the body is almost invisible in the middle of everything.

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Detail. Vinyl paint on MDF, 100 x 140cm, 2007.

The details in each part (rectangles of Eucatex), or even, contrarily, the complementary relationship of one rectangle with another, face us with the part and the whole, in a dialogue where each rectangle individually or in a group is a protagonist, conversing to create a narrative. The margin of each rectangle, the limit of its borders is as much a place of passage, as one of interruption and of the symbolic.

The War We Have Not Seen. Unknown Author. Detail. Vinyl paint on MDF, 100 x 140cm, 2007.

The authors of the Colombian war painted lives cohabiting on the edge of tragic contradiction: murders, strangulations, barbaric acts using tools such as chainsaws amid the colorful exuberance and light of the Colombian jungle, well mapped and displayed as a strategy of war–the jungle is close to these people.

It is the feeling of disquieting strangeness (unheimilicht) that Freud speaks of that bursts through the initially bucolic images.24 The paintings confront us with the possibility of seeing “horror” close at hand. The strategy used by Echavarria is linked to the myth of Perseus, who in order to avoid Medusa’s certain death stare uses her image reflected on a polished shield to be able to look at and hence kill her.

The grandeur of the jungle, one tone over another, relaxes the eye, preparing the way for the violence depicted by the paintbrushes at the hands of those who have been both sufferers and perpetrators of the Colombian drug war. The borderline between civilization and barbarism is revealed in colors and paint.

The subject, immersed in war, represents himself. In many paintings we see and (re)see through shapes and colors, unconscious subjectifications in mere traces. Some of the authors depict themselves as immense figures in front of another subjected to violence. Others hide amidst the act that they cannot or will not see, painting themselves tiny, as if they had no voice.

In the jungle, hidden by greenery, the subjects inserted themselves into the landscape of some or other space-time of their memories. In rural cases, within the everyday life of the field. Some images almost ask us to link to an ideal space; sometimes this space is a piece of the painting, as if another place might be seen as possible, at other times a rainbow or a bright light erupts from the sky, illuminating common life.

For some of the 420 paintings in the collection of the Puntos de Encuentro Fundacion, Echavarria shared with us various readings and symbolic interpretations. About the work La massacre del Naya (The Massacre of Naya), for example, he told us that the red is not just a color chosen for its tone, but a result of associations and unconscious referents that take shape.

The diptych The Massacre of Naya, created by two authors, is extraordinary; it’s impressive, made by two painters. One was a former guerrilla. He gives us the detail, marks the territory (…) “Here is the bloody sky.” He divides the picture into two parts: on top, everything is perfect and people engage in their daily work; on the bottom, there is massacre. “It’s quite fascinating this dividing line because in this country many live on the “other side.” When they paint themselves in their work, they paint themselves small (…)”.25

Paint oneself /(re) see oneself/ frontiers of mirrors

The strategies of artistic practice shared by Echavarria offer the potent possibility of speech. The act of painting inaugurates the author/subject of the war into a game of meanings and signifiers that go beyond historical memory (the name of the project). Actually the subject and the game are part of a negotiation between memory, the conscious and unconscious, that the authors leverage in order to be able to see and reread themselves via language.

Revelation does not discover something outside, that was there unawares; the act of discovery weds creation with what will be discovered: our own being. In this sense, one can say without fear of incurring contradiction, that the poet creates being. Because being is not something given, upon which our existence rests, but something that is done. One’s being cannot rely on anything because nothing is its foundation. Thus, it has no recourse but to hold on itself, creating itself at every moment.”

Octavio Paz26

La guerra… is a zero state in which the placement of the subject, as Paz emphasizes, enables a “creation of self at every moment.” It enables a person to see himself in the process of a poetic making. It is not so much an emphasis on a space of awareness of a barbaric act that is at issue, but rather a process of construction and deconstruction of self.

One can say that what is in operation is the use of devices (creative means of registering experience) to enable the “autopoietic.”27 The paintings are image experiences: where doing, thinking, stopping, not speaking, and faux pas are in play. “When I choose to draw I remember other things I chose not to remember.”28 The testimony of Brazilian artist Eduardo Berliner approximates what happens to the deserters from the war, guerrillas, paramilitaries, and ex-soldiers of the Colombian army. As revealed by Jhon Jairo, project participant when interviewed:

I think to make this work was to unload all remembrance. One dies, and who gets the memories? Nobody. I believe that here we could show what was kept inside, painting collaborates, enabling us to tell more and more.”29

The work done by artist Almir Mavignier (1925 – ) in the Studio of Painting and Modeling of the Department of Occupational Therapy at the Psychiatric Hospital of Engenho de Dentro, Rio de Janeiro (currently the Museum of Images of the Unconscious) parallels the attention to process, the act itself, that we see in Echavarría’s proposal.

From 1946 to 1951 Mavignier was responsible for the painting studio at Engenho de Dentro. Invited by the psychiatrist Nise da Silveira, then director of the hospital, the artist worked with Emygdio–a hospital patient and participant in the workshop, where he painted obsessively. Mavignier used the strategy of constantly changing the canvas, so the artist/patient could continue, in series, a thought process. Similarly, Echavarría made possible, using rectangles of Eucatex, a space of contact, where within one and the same painting it is possible to inhabit different worlds and to expand the insertion of self within the whole.

Mavgnier and Echavarría, although separated by more than 50 years of history, are attentive to and patient with the encounter, drawing up strategies, practices, so that the contact of the other with reality could be transmuted into “new form and color,” not idealized by the artist, but created by the other, refusing the mirror of self and world for a zone of unpredictable contact.

I’ll need to take care not to surreptitiously use a new third leg that can grow back in me as easily as a week, and then call that protective leg “a truth.”

But I also don’t know what form to give to what happened to me. And for me nothing exists unless I give it a form. And…and what if the reality is precisely that nothing has existed?! Maybe nothing happened to me? I can understand only what happens to me, but only what I understand happens…what do I know about the rest? The rest hasn’t existed. Maybe nothing has existed! Maybe I have merely undergone a great, slow disintegration. And my struggle against that disintegration is just that: is just trying to give it a form. A form gives contours to chaos, gives a construct to amorphous substance…the vision of an infinite flesh is a madman’s vision, but if I cut that flesh into pieces and spread those pieces over days and famines…then it will no longer be perdition and madness: it will be humanized life again.”Clarice Lispector30

Perhaps contact, for an experience

How, then, could I now start thinking?”

Clarice Lispector31

In Cartografia Sentimental, Suely Rolnik invites us to reflect on a language that dares the limits of life, of a power that doesn’t attach itself to a moral question, but rather to a social ethic that proposes the reinventions of worlds. Such a possibility presents itself in the desire of the body (the resonant body), one that places itself within the singularity of a situation, in language. The cartographer is the one who invents bridges that cross, that realize themselves in language: “You see, language, to the cartographer, is not a vehicle of messages-and-salvation. It is, in itself, the creation of worlds. A flying carpet… A vehicle that promotes the transcription of/for new worlds; new forms of history.”32

War means the domination of the body and the suppression of the invention of worlds. War is the greatest symbol of a state of annulment; its goal being to paralyze what exists, the “invalidation of flying carpets.” Thus, the greatest act of conquering a symbolic space would be to prevent the movement of bodies. The most brutal impact of this was shown after the rise of imaging technologies that allowed photographs to circulate of piles of bodies of Jews, killed in gas attacks during WWII (1939-1945). Bodies as a jumble of clothing: the symbolic containment of the body and the image of that contention are the ultimate tools of an ideology of containment.

A state of radical imposition that invalidates a life force cycle provokes various social symptoms that silence the potential of speech. Suely Rolnik also points out that these abuses of political suppression are radical triggers for our subjectivities. What can these muffled bodies still tell us? How can they speak? And if they speak, how and from where would they speak?

In “Experience and Poverty,” Walter Benjamin, says that experience is what silences. With that he meant that speech, a statement after the experience of war, would not be possible, only silence.33 There is something that mutes in the processes of deep trauma, disrupts.

If we go back to look at the paintings of La guerra… we also find in them the impossibility of speech, as noted by Benjamin, or even, in some cases, a search for a contact that is not established. There is something more complex going on than just giving someone the ability to talk about their trauma with paintbrushes. This is a project where the artist provokes language (through the technique of painting) to create images. However, in this way, a system of communicative negotiation comes into play, and silences, denials, unpredictability, inventiveness, and emptiness become part of the practice. Images here are also traces or communicative markings.

So-called autobiographies could be seen to be indistinguishable from fiction in the first person, if one accepts that it is impossible to establish a referential pact that would not be illusory (in other words: readers can believe in them, even the writer can write with this illusion, but nothing guarantees that this establishes a verifiable relationship between a textual self and a self of lived experience), as in fiction in first person, everything a “memoir” shows us is the speculative structure that someone, who calls himself I, takes as their object. This means that this textual “I” brings into play an absent “I”, and covers his face with this mask.”

Beatriz Sarlo34

Multiple biographies of affection

Or telegraph signals, the orchestra of sounds

An act of our activity, of our actual experiencing, is like a two-faced Janus. It looks in two opposite directions: it looks at the objective unity of a domain of culture and at the never-repeatable uniqueness of actually lived and experienced life.”

Mikhail Bhaktin35

I’m stalling. I know that everything I say is just to put it off–to put off the moment when I’ll have to start talking–knowing that there is nothing more for me to say. I’m putting off my silence. Have I been putting off silence for my whole life? But now, in may disparagement of the world, perhaps I’ll finally be able to start talking.

The telegraph signals. The world bristling with antennas, and here am I receiving the signal. I’ll be able to do only a phonetic transcription. Three thousand years ago I lost my head, and all that was left were phonetic fragments of me. I’m blinder than before. I did see, I really did. And I was terrified by the raw truth of a world whose greatest horror is that it is so alive that for me to admit that I am as alive as it is–and my most hideous discovery is that I am as alive as it is–I shall have to raise my consciousness of life outside to so high a point that it would amount to a crime against my personal life.”Clarice Lispector36

The project La guerra… operates using complex speeches that intertwine, add up, multiply, and individualize themselves. Echavarria, always emphasized, in interviews, that he did not influence the process of the painting workshops, his work he sees as being in the invitation to the other, in the offering of a space for participants, without any influence of art history or painting, to exhibit the affections and historical memory of war of their authors.

However, it is imperative to note that every provocation of speech is also imbued with an intention of listening. Echavarría is the proposer of an “aesthetics of existence”; at the same time his speech, his biography, is also present, either as an artist or via his very existence: as a man, a Colombian citizen, or at the junction and permeability of these roles.37 As an orchestrator of this process, his listening is affected. His voice is part, both in the encounter with his own questions about voice in this country at war, as it is also part of a voice that speaks inside of an art circuit, one that does not belong to the world of the participants.

For Bakhtin every sign is ideological, it reflects the field of social structures when interior discourse is visualized in an enunciation. There is a complex of voices at play in La guerra … where the proposition triggers particular biographical voices, which are inaugurated in the act, but also insert themselves in the social whole, in one given moment, the singular and the cultural, are multiple enunciations.

Echavarría’s project provokes language as a complex social game: the war and the assassin, the artist and art circuits, authorship: artist or participants? As Deleuze points out: “Art is what resists: it resists death, servitude, infamy, shame” so it is able to transgress “social organizations” by the power of poetic language that is in a founding moment.38 The visualization of paradoxes in the circulation of voices, where they go, who they talk to, does not impose a negative reverberation within a field of multiple voices, subjectivities operating in a sound body, which realizes itself in part and in whole, that cannot be apart from each other.

La guerra… is a body of biographies of multiple voices that, inserted into systems of contemporary art, calls into question the reverberations of these voices: Do they speak when hung as paintings in museums? The voices born of shared processes in workshops that lasted more than two years? Which voices are operating in the project? The voice of a 420-paintings-strong archive? The voice of personal legacies? Ideas about a war? The exhibition and selection themselves as speeches?

How does complexity play itself out in practice? The artist as belonging to this society at war, from what place does he speak of the war? In what ways does it affect his body and subjectivity? How, beyond being a proposer, can he can be looked at as he looks?

La Guerra… navigates a fine line of contact between the power of practice, experience and its subsequent insertion into the institutional circuit of contemporary art. But, as art, it goes beyond the social. Reminiscences, poetic states, small gestures of moments of survival are what stay with us as speeches for infinity.

Special thanks to the Juan Manuel Echavarría, for generously sharing his work and process; Casa Daros for providing the images and enabling the development of this research and Revista MESA for the invitation.

–

Trans note: Where published translations were available these sources have been used. If not noted, material has been freely translated for the purposes of this article.

1 Clarice Lispector. The Passion According to G.H. Trans Ronald W. Sousa. University of Minnesota Press, 1988 (A paixão segundo G.H, 1964) p.13

2 Casa Daros, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, inaugurated in 2013, is an institution of the Daros Latinamerica, one of the most comprehensive collections dedicated to Latin American contemporary art, based in Zurich, Switzerland. Daros Latinamerica has more than 1,200 works, including paintings, photographs, videos, sculptures, and installations of more than 117 artists, and continues to expand. In addition to exhibiting works in its collection, Casa Daros is a space for art, education and communication, housed in a former 19th-century neoclassical mansion, part of the historical patrimony of the city of Rio de Janeiro. Via its Art is Education program Casa Daros presents various proposals and projects, in which the artist and their creative processes are emphasized in exhibitions, workshops and lectures. The building was designed by architect Francisco Bethencourt Joaquim da Silva (1831-1912) and encompasses an area of over 12 thousand square meters, in Botafogo, Rio de Janeiro.

3 The term “private war” was used for Rodrigo Pimentel, ex-captain of BOPE (Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais (Battalion of Special Police Operations) and by João Moreira Salles in the documentary that portrays the daily lives of drug dealers and residents of Santa Marta favela in Rio de Janeiro (1997-1998). In the film, Salles addresses, via interviews with police, dealers and residents, the web of entanglements that generate a war where the State is an accomplice and promotes social apartheid propagated in statistics that hide the face and life of exclusion, driven by the perpetuation of poverty and historical slavery, where blacks and poor are doubly victims of an unwelcoming State. Now, at the time of this writing, we have a new reality with the UPP (Unit of Pacifying Police), still very complex. Santa Marta is considered a “pacified” favela, but current panorama demonstrates the perpetuation of hidden violence, by virtue of not acting within the complexity of poverty and the continuous lack of access to public services.

4 This period was characterized by disputes over land ownership in the Colombian countryside – the main reason that triggered the conflict between peasants, liberals and conservatives. The beginning of this war for many historians was the death of Eliécer Gaitán in 1948, a leader of the liberal party that fought against land monopolies.

5 Testimony of Juan Manuel, interview on April 3rd, 2012 at the artist’s studio in Bogotá, Colombia.

6 Laurel Reuter. “Una conversación: Juan Manuel Echavarría y Laurel Reuter.” In: Juan Manuel Echavarría: mouth of ash = bocas de ceniza. Milano: Edizione Charta, 2005. p.72

7 The word “desplazado” literally means “displaced ones,” referring in particular to those who are forcibly displaced by war.

8 In Matar, rematar y contramatar (Killing, rekilling and counter killing) Colombian anthropologist Maria Victoria Uribe develops a sociological analysis of violent processes triggered from the “La Violencia” period and describes the cuts and mutilations used on the corpses as both symbolic and strategic means of disappearing with the bodies. Maria Victoria Uribe. Matar, rematar y contramatar. Bogota, DE: Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular, 1990.

9 The word “author” referring to participantes in the project is used throughout the article intentionally, first as a way to draw attention to the notion of authorship, secondly in order not classify the participants as assassins of war, nor as artists. The proposal of La guerra… creates a suspended space away from socially rigid classifications.

10 The term “body of multiple voices” comes from Bakhtin and was primarily in the book Marxism and the Philosophy of Language from the point of view of construction of meaning, where text – discourse is permeated by voices of different enunciators, sometimes agreeing, sometimes dissonantly characterizing the phenomenon of human language as essentially dialogical and therefore polyphonic. View: Bakhtin, Mikhail (Voloshinov, Valentin Nikolaevich) [1929], Marxism and Philosophy of Language. Trad. Michel Lahud and Yara Frateschi Vieira. 13 ed. São Paulo, Hucitec, 1995

11 Juan Manuel Echavarría in conversation with Hans-Michael Herzog. In: Hans-Michael Herzog. Cantos cuentos colombianos: arte contemporânea colombiana. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó, 2013. p. 10 – 11.

12 The Justice and Peace Law (Law 975 of 2005) was driven by the government of Álvaro Uribe Vélez and approved by the Colombian Congress as a legal framework to regulate the demobilization of paramilitaries in Colombia. Eventually it could be used in the demobilization of guerrillas process, but so far FARC has not reached an agreement to lay down their arms.

13 The Fundación Puntos de Encuentro (Meeting Points Foundation) is a nonprofit organization created by Juan Manuel Echavarria in May 2006 whose goal is to promote, support and create alliances and to display art projects that preserve the historical memory of the war in Colombia.

14 See note 3

15 Ernst Bloch. The Principle of Hope. Volume One. Trans: Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice and Paul Knight. Cambridge/Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1995 (Originally published as Das Prinzip Hoffnung, 1959). p. 3.

16 Ibid p13.

17 The peak of La Violencia was El Bogotazo, large proportions of urban revolt that culminated in the occupation of the Presidential Palace and destruction of the center of Bogotá.

18 Miguel González. Colombia: visiones y miradas. Cali: Feriva, 2010. p. 161.

19 See Revista Caros Amigos, nº 177/2011, pp. 40 – 45:

20 José Ignacio Roca. Transhistorias: mito y historia en la obra de José Alejandro Restrepo. Bogotá: Biblioteca Luis Angel Arango; Banco de la República, 2001.p. 58.

21 Transcription derived from a lecture by Suely Rolnik at the International Anthropophagic Meeting. Sesc Pompéia, São Paulo, december, 2005. Available (portugueseonly): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vil8cWpGsIc (Accessed April 3rd, 2014).

22 Eduardo Galeano. As Veias Abertas da América Latina,1976. p.24.

23 Lispector op.cit p.166.

24 S. Freud, Le inquietante étrangeté, art. Cited in Didi Huberman, O que vemos o que nos olha. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2010, p. 216.

25 In an interview on 03/04/2012 at the studio in Bogota, Colombia, Juan Manuel narrated and showed the work in every detail: the elements of the framework, the dead, the red cross.

26 Otavio Paz. O Arco e a Lira. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1982. p.187.

27 The concept of autopoiesis was used in the early 1970s in biology by two Chilean biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela arguing against a notion of a living being as a given machine, but rather as a state of being in a process of constant production ceaselessly engendering its own structure. This concept soon began to be used by many fields of human knowledge, and in philosophy in particular with Deleuze, Guattari, Foucault and others.

28 Eduardo Berliner is a 35-year-old painter based in Rio de Janeiro. His work grew out of drawings in notebooks and photographs of everyday life, as well as assemblages of objects that he uses as reference for his paintings.

29 Interview with Jhon Jairo Camacho on April 3rd, 2012 in Echavarria’s Studio in Bogotá, Columbia.

30 Lispector op.cit p. 6.

31 Ibid p.7.

32 Suely Rolnik. Cartografia sentimental. Editora Estação Liberdade, São Paulo, 1989. p.18.

33 Walter Benjamin. Magia e técnica, arte e política: Obras escolhidas I. 10. ed. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1996.

34 Beatriz Sarlo. Tempo passado, cultura de memória e guinada subjetiva, UFMG, 2007, p. 31.

35 Mikhail Bakhtin. Toward a Philosophy of the act. Trans: Vadim Liapunov. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993 p. 2.

36 Lispector op.cit. p. 14.

37 Michel Foucault. Une esthétique de l’existence (entretien avec A. Fontana), Le monde, 15 – 16 juilet 1984, p.XI.

38 Gilles Deleuze. Conversações. São Paulo. Editora 34, 1992, p. 211.