Tides Program in Rio Grande, RS. Photo: Cristiane Barcellos

Poetic Resurgences: The Tides Program and the City

Rafael Silveira (Rafa Éis)

In nine editions of the Mercosul Visual Arts Biennial, held in Porto Alegre in Brazil’s southern state of Rio Grande do Sul, many amazing people have dedicated themselves to this great contemporary art event’s Pedagogical Project, making it a recognized center of poetic-experimental education.1 I speak of mediators, teachers, students of all ages, artists, producers, visitors, curators, researchers, families, in short, people who have experienced art as a form of self-invention in collaboration with others through the actions of the Pedagogical Project of this institution. Generations of art educators and educator artists have been trained in the interstices of poetry and pedagogy, creating extradisciplinary territories, places in the shadow of the spotlights of institutional spectacle.2

It is from this place and with the desire to produce critical thinking in relation to the experience of a special program with educators, and also to act as a witness to these seldom spoken of events, that I bring news.3

The 9th Mercosul Biennial | Porto Alegre presented in 2013 – under the title Weather Permitting - focused on “the interaction between nature and culture, and the ways in which visual artists refer to the unknown, the unpredictable and apparently uncontrollable phenomena”4. Methodologically independent from and conceptually intertwined with the curatorial project, the 9th Biennial’s pedagogic program, Cloud Formations, developed and articulated a series of experimental actions, not only in the city of Porto Alegre – the capital of the state of Rio Grande do Sul and home to the major exhibitions of the biennial – but also in several cities throughout the region, as we shall see. Under the pedagogical coordination of Mônica Hoff, also one of the 9th Biennial curators, and engaging the most diverse of audiences, Formations was the most daring and experimental series of actions ever developed by the Biennial’s pedagogic project. In the words of Mônica Hoff:

Cloud Formations, the proposal of the 9th Mercosul Biennial | Porto Alegre pedagogic project, aims to enable encounters, activate relations, and act as a corporal and social body. As an integrated training initiative for educators, mediators, the public and the art aficionado, education in the 9th Biennial expands in space and time in order to bring into dialogue, in a single network, agents commonly located in isolated systems.”5

“Formations” brought together a conglomeration of programs celebrating the poetics of otherness and the pedagogies of invention.6 Among them was one reserved for teachers: the Tides Program. It was here that I dove in. It is this dive that I will discuss a little in this essay, hoping to bring at least in some small way the breeze of its “wave-memories” to this small glass of “wordwater”.

The Becoming-Tide of Art

In the same year of the Cloud Formations program, the streets of many cities in Brazil became fields for a series of clashes about public space. The right to the city, the competition for urban mobility, decisions regarding “sensible”, as Rancière notes, and symbolic territories, the privatization of public spaces, forced relocations, the state of exception instituted at the time of the World Cup of Football, and state control and violence: these were all issues placed on the agenda by the crowds on the streets.

Demonstration in the city of Porto Alegre, RS. June 2013. Photo Ramiro Furquim/Sul21. Image taken from material written by Samir Oliveira: “2013: the year that didn’t end.” (Available in Portuguese only) Read it here

With an intense agenda of demonstrations and protests, students, community groups, teachers, and social movements took over the cities in all regions of the country, flooding streets, avenues, town squares, and plazas with a sea of people. Over the course of 2013, MPL (Free [Bus] Pass Movement), the direct action tactics of the black blocs, the Ninja Media and several other groups and social movements become well known throughout the country. Numerous independent collective communication groups staged independent coverage and transmission of events, in particular using online networks for the production of imagery and audiovisual testimonies of excessive State violence. The street was experienced and narrated from many perspectives.7

From the perspective of the police, a street is a space of circulation. The protest, in turn, transforms the street into a public space, into a space for community issues. From the perspective of those who send the forces of order, the space for community issues lies elsewhere: in public buildings intended for this use, with people destined for this function. Thus dissent emerges, before being characterized as the opposition between a government and contesting peoples, it is a conflict over the very configuration of the sensible.”

Jacques Rancière8

Inevitably, heated disputes for representation occurred in this scenario: in social networks, in party propaganda and ads, television materials, videos and the streaming of independent media groups, even informal conversations of the type that occur on the bus and in line at the supermarket. In short, everywhere speeches and images were coupled with the protests pulling and stretching the events on the streets in all possible directions.

When in the same year, myself, Luciano Montanha and Letícia Bertagna, three artist-educators, began, with Mônica Hoff, to plan what would be “Tides”, the program already had a name, but not yet a body. We were a group of artists with similar affinities of practice and interests: Letícia’s poetics embrace the encounter with the other; and Luciano and I had already shared experiences between art and education. Also, key to the conception of the project was the idea of the encounter with the climate.

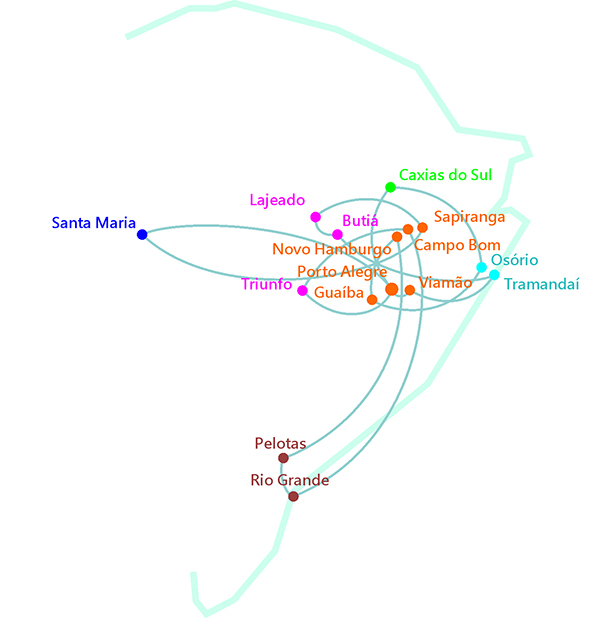

While teacher training had been a regular feature since the first editions of the Biennial, we were interested in experimenting with distinctly different strategies, and above all in extra-mural contexts. In 2013 the socio-political context summoned our bodies to occupy common space. The weather was permitting and the soil fertile for creation: 15 cities throughout the state of Rio Grande do Sul as a ground to think and artist with teachers working in various areas of knowledge and at different grade levels.9

Soon, we saw a great possibility for artistic experimentation, pedagogy and micropolitics.10 We also thought that, like the experimental web that was weaving together the Cloud Formations program as a whole, “Tides” should be open to the singularities of the energies inaugurated at each of its encounters. Thus, embracing a complex array of forces and embodying the natural tidal phenomenon itself as a means of working, we designed possible modes of navigating the journey between cities. We set sail for unforeseen encounters and the winds of affection.

The tidal phenomenon happens via the gravitational forces of the interactions of the sun and moon on the ocean. These forces, if combined with the action of wind on the sea, can produce a beautiful natural event called resurgence. This event is important for the renewal of the maritime food chain and occurs when the waters of deeper layers, rich in nutrients, rise to the surface. When nutrients, previously inert, rise up to the illuminated layers of the ocean via photosynthesis, algae use them to produce micro-algae, zooplankton, which in turn provides food for small fish.

What interested us here is how this relation of forces produces, via the resurgence of deeper layers up to the surface, the creation of nutrients that will maintain the oceanic food chain. Attracted by the beauty of this movement, we dislocated it from oceanography and relocated it within the imprecise boundaries of art and education. We were interested in stimulating affective resurgences: finding the discourses and images not visible to the eye, bringing them to the surface, turning them into food for poetic production with the city, affecting and being affected by the relationships that make up the common. The “becoming-tide” of art.

The Territory and the Strategy

The challenge is to free ourselves from the pseudo-movement that makes us stay in the same place, and probe what kind of medium a city could be, which affections it favors or blocks, which paths it produces or captures, which becomings it liberates or suffocates, which forces it binds or disperses, which events it engenders, which potentials lie cowering within it and waiting for which new agencies.”

Peter Pál Pelbart11

Rio Grande do Sul is a state full of nuances and forms that seem to betray the image of Brazilianness that conjures beautiful beaches, samba and a tropical climate. In the extreme south of the country these colors see dawns covered with frost. Landscape and harsh winters intertwine with the contradictory narratives that make up the constitution of the gaucho identity. In many cultural and climatic aspects the Brazilian south is closer to its Spanish-speaking neighbors, Uruguay and Argentina. Even the gaúcho (ethnic moniker used to describe people born in Rio Grande do Sul) comes from the term gaucho (a farmer/man from the country) used in our neighboring countries. Under the strong influence of European culture (mainly due to Italian and German immigration), black and indigenous cultures, although very present in our customs and essential aspects of the state constitution, nevertheless resist the dominant narratives of construction of the Rio Grande do Sul. The seas in which we were navigating were awash in the multiplicity of colors and smells, textures and accents bathing Brazil.

Image 1: Location of Rio Grande do Sul on the map of Brazil.

Image 2: Dislocation. Tides Program in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. Photo: Luciano Montanha.

Our intervention strategy with local educators in these cities included different moments: the collective creation of poetic repertoires; attention to listening and the production of a discourse that both reflected and embodied multiple voices; the collective creation of poetic situations in public spaces of the city; and finally, sharing of the experiences of these actions with a discussion of potential resonances in school contexts. This methodological approach was embraced throughout long encounters. We spent eight hours in intense activity with the teachers. The duration of each step could vary according to the responses of the groups. Each city had its own climate, landscapes and winds.

A Shell to the Ear: Listening

Butiá was the destination for our inaugural expedition. A small town with a little over 20.000 inhabitants. Despite being named after the tree that yields a tiny fruit typical of the south, the city’s economy and history was built on the coal industry, which had its peak production between the 1940s and 50s. Today, the landscape of Butiá suffers huge wounds originating from the extraction of open pit mining.

On our first trip we met what would be our largest public: almost 200 teachers were waiting for us. But it was not only them: there was a whole sea contained in the clouds. Although the rain did not allow us to experience any kind of walking on the streets – only to discuss project possibilities – our dedicated listening allowed us to condense time and space.

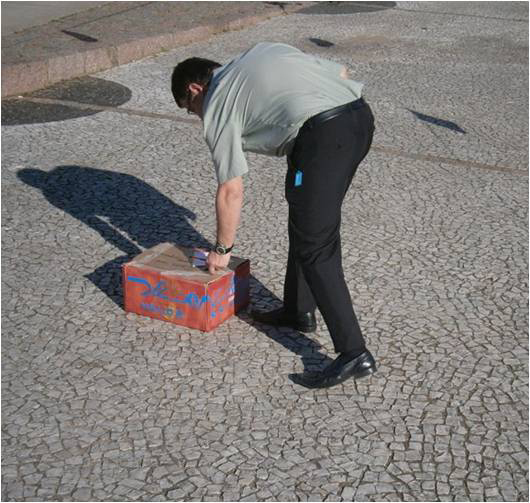

We were artists foreign to each city we visited (except for Porto Alegre), and as such, our desire was that the potency of the spoken word could transit amidst distinct voices and narratives creating places built from the experience of those who inhabited the city. So, as a means to trigger a discussion on the history and current situation in each of the cities, we used informational cards that were produced based on previous research. These cards featured news, images, and discourses on the city from different sources (articles in newspapers, websites of governments, institutional materials, companies operating in the city, the environmental news situation, political contexts, etc.).12

Teachers talk about their experience with the city in Butiá, RS. Photo: Letícia Bertagna.

The signs of the city’s coal past permeated the teachers’ voices: the rebirth of that which was rescued from the collapse of an underground galley, the care that the miners had with each other as life accomplices, the heartaches generated by the whistle announcing that not all the miners would return home.13 Gradually, this being our first experience with the city, we were taken by the teachers’ present memories connected, which were connected to the deep galleries of coal history that inform the subjectivity of Butiá. It became clear how the ways of this city’s life could be wrapped around a cloud of coal dust, which only became matter when it encountered any surface whatsoever to adhere to, whether the surfaces of houses, skin, lungs, or memory. However, we also heard about other city vocations, such as agriculture and even the expression of the desire for new paths, especially through art and culture.14

If It Isn’t There, We Invent It!

In the first state capital, the city of Viamão, the groups of teachers converted lack into abundance. Founded in 1741 on the banks of the Patos Lagoon, the city has 239.384 inhabitants and a vast territory that alternates between commercial centers and large green areas.

When we talked about the educational context of the city, many teachers referred to the lack of spaces for listening to enable them to exchange experiences about their teaching practices in the schools. This gap, although stated as a structural problem of the school as institution, reflected the increasing loss of spaces for popular participation due to how cities are administered, bureaucratization of time, and the imposition of work rhythms and modes of production that frequently superimpose themselves on the analytical space and transformative participation of micro-contexts.

At a time when the “crisis of representation” was forcefully returning to contemporary political discussions, it became urgent to act to reduce mediations, and to work on the production of speech in the first person, creating direct contact zones between people and contexts.

In a beautiful movement, groups of teachers drifting through the city produced as an intervention a proliferation of listening devices. These walking wanderings took place in small groups. At least three of the five groups participating in the encounter created alternative ways to listen to residents speak about the city itself in a strategy that was nothing if not the fruit of a contagious desire of caring with and for the other. A desire for change expressed in action.

Tides Program in the city of Viamão, RS. Photo: Group of teachers/unidentified author

Among the dedicated listening strategies created by the groups were the creation of a box/urn and washing lines that accumulated desires and expectations of people in relation to their city. From sheets of paper left out and hung by people on the streets, squares and schools we encountered all sorts of requests – from the desire for shopping centers and public hospitals to even sensitive and intimate suggestions. Artistic research methodologies sprouted focusing on the production of desires in the context of the city.

We did not worry about solving the problems discussed before our wanderings, but rather left things open to the possibility of development through artistic production. It was up to the participants of the game to invent their own dislocation strategy and actions: to let themselves be affected by the intense conversations and make up an action along the route or go in search of the unexpected, open to chance. One of the groups of teachers at the encounter in Caxias do Sul acted to bridge these two strategies.

Encounter the Other That I Am

It’s about an adventure. The goal of this adventure is adventure itself. Go. Experience. Basically be open to encounter: the encounter with the other, the encounter in the other, the encounter as a territory that changes at every access. The encounter makes the other real. And I make myself real the same as/with the other. At the same time, each of us becomes a fragment of these encounters within the world. The encounter makes real the effective translation of an event of creation.”

Ericson Pires15

The hegemonic representations of cities dispute the potential effectiveness of possibilities and impossibilities of the encounter with the other. Caxias do Sul – a city that has long been called “Campo dos bugres” (a derogatory colonist moniker)16 because of the presence of the indigenous Kaingang people – received in the second half of the 19th century a large number of Italian immigrants, which made grape growing and wine production the major bases of Caxias’ economy. This led to the city assuming an idealized self-image of the Italian immigrant.

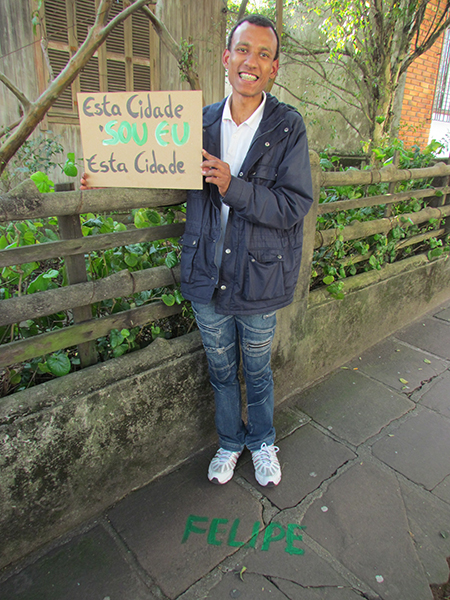

Collective Identity. Action and image produced by teachers of the city of Caxias do Sul.

As we listened to a group of young teachers, they harshly questioned this homogenizing stereotype. It became clear that the city no longer fit this already spent model, which in order to be established had meant exterminating the “bugres from the field”. In the current Caxias do Sul, the immigrant does not come from Europe, but from Africa, especially Ghana and Senegal. The socioeconomic situation of these countries has dislocated a large quantity of immigrants who try to find new ways of life in the gaucho city working in industry and commerce, mostly illegally and with low wages.

The questioning around the Caxias image began with the initial stage of conversation and listening, but it gained another language at the encounter with difference, body-to-body in the melee of the city. Patricia Parenza, an art teacher in non-formal education spaces in Caxias, talks here about the action created by the group of teachers with whom she participated at the “Tides” encounter:

Each person we approached told us a bit of their history: the origin of their surname; what city they came from; and how they identified with the city. After that, they held up a sign that read: “This city is me/I am this city”. Everyone was photographed and received a small gift of sunflower seeds […] We titled this activity: Collective Identity. After this, I felt that each of us preserves a bit of the history and identity of the place in which we live.”

Patricia Parenza17

Collective identity produced a visual testimony of a different city from that painted by the defensive discourses of a single identity for the municipality of Caxias. The portraits produced of different city residents created a collective image that suggested nothing of the homogeneous. The phrase “This city is me/I am this city”, repeated in all the photos, marks a kind of poetic alliance that affirmed difference (and not a bureaucratic contract that seals inequality). The name written on the street in front of each person, at the foot of the photocomposition, marked the place on the city map of the encounter’s location. Sunflower seed sharing celebrated this encounter, life as a potency to be cultivated.

Collective Identity. Action and image produced by teachers of the city of Caxias do Sul.

Seas and Winds

It would be impossible to cover in these pages the complexity of the contexts and actions produced in the encounters with teachers in the 15 cities visited by the Tides Program. I could speak of the flight conducted in Morro Ferrabraz by the teachers of Sapiranga, the listening project in Novo Hamburgo, the collective urban planning exercises in Santa Maria, the performance with time and sidewalk painting in Porto Alegre, the interruptions flows, the collective cartography, and more. Each of the teacher working groups produced many encounters that deserve long conversations.

Group of teachers working in Guaiba city. Photo: Luciano Montanha

The experience of the program made clear the importance of the dissolution of a centrality or discursive hierarchy with regard to any relationship that strove to offer a relationship of potency and not of power. Dialogue was only possible when one listened and the listening ran counter to institutional modes of operating and counter to old colonial practices that speculated and defined the place of the other by removing their ability to speak. It was necessary to escape speaking on behalf of the other and to avoid discourses intended to represent the other, which made them inferior.

The practice of qualified listening produces, above all, ways of qualified speaking. If we think of this exercise of listening interspersed with a sharing of contemporary artistic practices we have inevitably the collective creation of expressive repertoires. The words of Fatima Marques, professor of performing arts in the city of Santa Maria, are exemplary: “This to me is a beautiful path: build this cartography where I can go about multiplying my ability to say things”.18

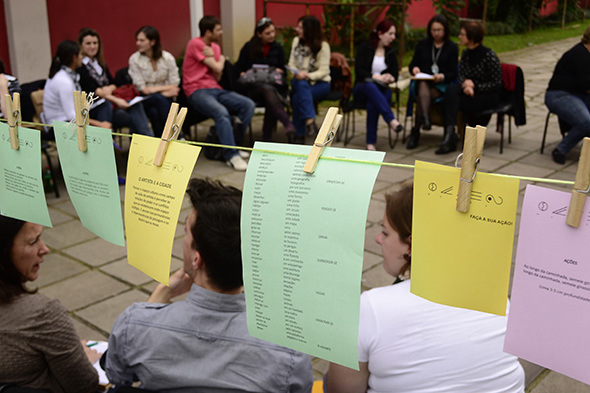

Clothesline with inspirational texts. Tides in Caxias do Sul, RS. Photo: Luciano Montanha

In this experience we can feel the materiality of the inseparable relationship between politics and language. For this reason, I refer to “Tides” as a political experiment: interfering in a certain discursive order common to many training environments and the given distribution of the sensible that represent certain ways of seeing the city. According to Rancière, “politics concerns itself with what can be seen and what can be said about what is seen, who has the competency to see and ability to say, the properties of space and possible time”.19

I am increasingly certain that you need to escape from certain modes of relationships grounded in control or the supervision of the creative or artistic experience. And this is exactly what Luciano Montanha spoke of, partner on this and other projects:

[…] I am talking about something that has been pursued for a long time within the field of art that is the approximation between art and life, this attempt to cross these two territories of existence. However, in general, the public live it vicariously through the experience of artists. In this case, perhaps the production of these teacher-artists will never be read as art by the art system, but it is created in a way, in a space-time, in a state of art making where one can proclaim, “this is art and here in this space I am capable of converting the time of life into a time of creation and artistic experience.”20

As artist cartographers, we were there to accompany processes and not to supervise them or give directions. We sought to intervene as little as possible in the teachers’ interventions. In this way we invented a practice that had the potential to make an intervention within a certain image of schooling and of education underpinned by a missionary-Jesuit gesture and within a certain image of art as an individual and distant production to the micropolitical here and now. Inevitably we operated a type of folding in and out of the institution via the permanent force of de-institutionalizing our practices and thoughts. To move and bend the institution is to incline its sails for the multidirectional winds of collective lungs; to propose deviations in the trajectories that define the institutionalization of art and of education.

We felt the challenge of being the subjects, the artists, those who modify the environment, that redirect people’s attention. It was a unique moment in that the challenge given to us took us to encounter a new perspective, a new vision of art.”

João Carlos21

The expressive output of the encounters was manifested in the action of the educator groups in each city. The actions congregated initial conversations around the practices of contemporary art, the encounter with the foreigners we were, the encounter with fellow teachers, the encounter with the city, with chance, with memory, with the unknown. In this way an ethics of art is produced grounded in the encounter as a creative force. As Ricardo Basbaum tells us:

The work of art is made from the ability to divert the flow of things that, at some point, should pass by there. It is a complicated calculation, not linear, that does not point toward the satisfaction of a will: any work of art involves a constant listening, a permanent state of attention.22

In addition to the previous experience of teachers with each context, there was a whole synergy of forces condensed in moments of conversation, soon to expand into the city, and return to the group as a tale of an adventure and the sharing of repertoires, to afterwards, dislocate to schools aiming to at least climb its walls (the concrete ones and those microscopic ones that surround our relation with the world). At the same time, who knows, tear them down in a contagious ethic of sharing.

I conducted with my students interventions within the neighborhood where the school is located, with walks, reports, photos, neighborhood map drawings, an official report to those responsible in the government asserting the need for improvements to the neighborhood. Within our school we also “revolutionized”, we cleaned the patio, we cleaned and made flowerbeds, cleaned the bushes/wood areas that had parts that were not being used by school. I was very excited and managed to excite students and many teachers as well.”

Helenize Ortnau Cirio23

Teachers share experiences in their ‘wanderings’ in Porto Alegre. Photo Luciano Montanha

When I mentioned earlier in this essay that we had embodied the tidal phenomenon as a means of working, it wasn’t just a metaphor, but something very concrete and powerful as a strategy for the mobilization of forces. Forces that, when in movement dislocate other forces, which in turn dislocate other forces and so on, affecting and being affected by its errant dislocations.

It is from the desire to dislocate that experience has its beginning. Dislocation, or to set oneself in motion, is the drive to locate oneself somewhere else, to find oneself in another place, other than my own, where I am. To move oneself is to do, is to produce the possibility of the other, the other place, the other me outside of my place.”

Ericson Pires24

The Tides Program was, above all, an expanded experiment of dislocation: the dislocation of a natural phenomenon for artistic practices, dislocation of the body to distinct regions of the state, dislocation of poetic and educational practices for zones of contact with the city and with the other, dislocation of control for availability, dislocation of listening to action, dislocation of profound layers to the surface, dislocation of thought, dislocation of power for potency; and finally, an incessant dislocation of what we are to what we may turn into.

Moment and space of action. Tides in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul. Photo: Luciano Montanha

Perhaps this was one of the most beautiful – among many other possible and impossible – meanings of publicness in art: dislocation. It is dislocation that can multiply and weave the meanings of art and publicness according to its qualitative forcefulness as the micropolitics of art. That which dislocates moves in the measure with which it is moved. When I dislocate myself I become the other that I am; transforming, I am transformed. Leaving what is given us to make, resurging what is in front of our eyes, creating nutrients for a poetic-political practice. Dislocations and resurgences of difference. The becoming tide of art.

_

1 Inaugurated in 1997, the Mercocul Biennial of Visual Arts takes its names from the Southern cone MERCOSUR economic treaty and draws on class biennial models from the Biennials of Venice, Italy to Sao Paulo, Brazil. Based in the city of Porto Alegre, in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul the biannual event initially focused on artists from Latin American counters within the MERCOSUL, but quickly began to involve artists from around the world in its later editions and to extend its actions to other cities. Today the event – headed for its 10th edition – has established itself in Porto Alegre and the state, especially with the actions of its Pedagogic Project. For more information on the Biennial and the history of the pedagogic project see Mônica Hoff. “Educational curatorship, art methodologies, training and permanence: the change in education at the Mercoul Biennial.” In: Helguera, Pablo and Hoff, Mônica eds. Pedagogia no campo expandido. Porto Alegre: Fundação Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul, 2011, ps. 382-391.

2 Brian Holmes. “Investigações extradisciplinares: Para uma nova crítica das instituições.” Revista Concinnitas, volume 1 ano 9, número 12, ps. 7-13, julho 2008.

3 I refer here both to the poor visibility given to the program for teachers presented here (perhaps the necessary condition for the existence of actions that are intended to bend some of the rigid structures of the institution), but also, more broadly, to the limited presence of discussions informed by events like this in the critical art circuits.

4 Sofia Hernández Chong Cuy. Weather Permitting. Porto Alegre: Fundação Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul, 2013, (Catálogo), p.32.

5 Mônica.Hoff. “De uma chuva de ideias às Redes de Formação”. A nuvem. In: CUY, Sofía Hernández Chong & HOFF, Mônica. A Nuvem: Uma antologia para professores, mediadores e aficionados da 9ª Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul | Porto Alegre. Porto Alegre : Fundação de Artes Visuais do Mercosul, 2013, p. 20.

6 Cloud Formations comprised Conversations in the Field, Mediation Laboratories, Homemade Inventions, Tides, School of Inventions, Pollen, publications, and finally educational visits. It is important to remember that in addition to these programs, there were several activities created and performed by mediators such as chats, evening parties, parades, and experimental educational visits.

7 David Harvey et al eds. Cidades rebeldes: Passe livre e as manifestações que tomaram as ruas do Brasil. São Paulo: Boitempo: Carta Maior, 2013.

8 Jacques Rancière. “O Dissenso”. In: NOVAES, Adauto (org.). A crise de razão. São Paulo: Cia das Letras e Funarte, 1996, p. 373. (N.T. Free translation)

9 The cities: Butiá, Campo Bom, Rio Grande, Pelotas, Novo Hamburgo, Guaíba, Osório, Caxias do Sul, Porto Alegre, Viamão, Tramandaí, Triunfo, Lajeado, Sapiranga, and Santa Maria. The Tides itinerary coincided with the trajectory of the program Conversations in the Field. We chose each city based on its uniqueness in terms of climate and socio-political context, as well as on their vocation to certain modes of energy production.

10 “The problem of micropolitics is not at the level of representation but at the level of subjectivity. It refers to the modes of expression that are not just articulated via language, but also by heterogeneous semiotic levels.” GUATARRI, Felix & ROLNIK, Suely. “Micropolítica: Cartografias do desejo”. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes, 1986, p. 28.). (N.T. Free translation)

11 Peter Pál Pelbart. “Vertigem por um fio: Políticas da subjetividade contemporânea”. São Paulo: Ed. Iluminuras, 2000, p.45. (N.T. Free Translation)

12 Used as a game, we worked with informational cards as a way to launch listening situations, action and thought processes. We adopted this strategy in all our encounters. In between trips, Leticia and Montanha and myself evaluated the encounters, analyzed possible methodological changes and conducted general research in order to generate material for the cards. Starting from the meeting in Novo Hamburgo we put these cards on clotheslines, for the most part hung out in the open.

13 Based on a teacher’s report that the miners’ union sounds a whistle outside of hours when there has been a fatal accident at work, most of the time because of the collapse of underground galleys.

14 Due to the bad weather, rather than go out to the streets, we conducted projects of poetic actions to be developed in the city. In these projects the teachers explored artistic initiatives and poetic activities for the public squares and places of occupation of the city that would install groups of artistic and cultural activity in the city.

15 Ericson Pires. Cidade Ocupada. Rio de Janeiro: Aeroplano, 2007, p.11. (N.T. Free translation)

16 Bugre was a term often used to characterize indigenous groups. Of pejorative usage derived from the time of slavery. The term connects the indigenous with the savage, pagan or uneducated (perspectives of those who opted to subjugate life in favor of callous powers).

17 Statement sent by Patricia Parenza via a questionnaire that collected multiple perspectives of the teachers who participated in the Tides encounters.

18 Account drawn from a mini-documentary that the Tides program produced on the city of Santa Maria.

19 Jacques Rancière. “A partilha do sensível: Estética e política”. São Paulo:Editora 34, 2005, p.17. (N.T. free translation)

20 Statement made as part of the project “Meanings of publicness in art” that is part of this case study featured on Revista MESA no.3

22 Ricardo Basbaum. “Quem é que vê nossos trabalhos?” Seminários Internacionais Museu Vale 2009 – Criação e Crítica (2009), p.202. (N.T free translation)

23 Cirio lives and works in the city of Rolante and was in Novo Hamburgo to participate in the Tides encounter.

24 Op. cit., Pires p. 197.