Mediation Lab with Valquíria Prates. 9th Mercosul Biennial. Photo Eduardo Seidl

Publicness at the Mercosul Biennial: The Biennial as School, the City as Curriculum

Mônica Hoff

Over the course of its history, the Mercosul Biennial has shaped a path with rather curious deviations. Taking its name from a southern cone economic agreement that never caught on and finding itself in an impossible context, somehow, over the years it achieved more than it intended, and little is known about this.1

Founded in Porto Alegre, the capital of Brazil’s southern state of Rio Grande do Sul, in 1996 and presented for the first time the following year, the Biennial’s existence is linked to a broad set of paradoxes. Apart from its relationship with an economic treaty, the Mercosul Biennial was born of the desire to counter History with an upended south-to-north alternative, and it thus ran the risk of being equally missionary; it desperately courted the public, but did so from an entrepreneurial mindset; it wanted to be libertarian, but operated according to old canons, with old methodologies; it wanted, as a goal, to be big and democratic – perhaps the pinnacle of its contradiction – but when it got there, it did not recognize it.

Yet this trajectory is just one of the known Mercosul Biennials – one, that like many art biennials, is organized from utopian parameters that have as their measure their own institutional limitations. Beyond this version of the Biennial exists at least one more, one that is less orderly, more organic and porous, potentially affective and transformative. This is the one we will focus on throughout this essay.

Recognized as an experimental and expanded educational initiative, the Mercosul Biennial built, during its nine editions, a place beyond its contradictions and predicates as a demonstration of international art of transatlantic proportions.2 More than a large temporary exhibition, it became a kind of free and decentralized school in a permanent state of latency with a bi-annual program and public curriculum, which had the local community, not only as its main spectator or interlocutor, but as its main critical agent and teacher: a “periodic school that pulses through the city every two years”, as Dominic Willsdon, the curator of education and public programs at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and also part of the 9th Biennial curatorial team, recently pointed out.3

At first glance, we could say that this phenomenon is due to the creation of an education curator for the 6th Biennial by the then chief curator, Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro, conferring upon the exhibition new meanings for education in the context of the Mercosul Biennial.

Seen as one who, as part of the curatorial team, would be a public spokesperson, the education curator did not emerge as a secondary or subordinate figure assuming educational responsibilities in the broader context of the institution or seeking to illustrate what the chief curator established as central, but rather as someone who could suggest or create some good problems as much for the curatorial team as for the institution.

The creation of this role – the responsibilities of which were fully and forcefully assumed by artists for four editions4 – established a long and broad deviation in the meanings of art and education intended by the Mercosul Biennial. It paved the way for an artistic practice increasingly intertwined with education, drawing on the active participation of artists in educational activities proposed by the educational program and on pedagogical thinking that went beyond the context of the classroom, didactic materials, training courses focused solely on large exhibition visitation, and instead moved toward the creation of new forms of art agency. This important detour lasted for the next three Biennial editions and engaged with gradually transforming the Biennial’s expository and temporary modus operandi into a critical platform pushing for permanence and an unquestionably public orientation.

In his pedagogical proposal for the 6th Biennial, a sort of pilot project for the future of the institution, Uruguayan artist, educator and critic Luis Camnitzer, then education curator, put forward:

1. The Biennial defines itself as an institution of permanent cultural action within which the periodic exhibition (bi-annual for the time being) is only one of the activities. In this case, its main activity is to illustrate and promote the other. […]

2. In terms of training […] of mediators and […] public the Biennial self-defines itself as a mini-university.5

Luis Camnitzer, curator of the Pedagogic Project talking with mediators. 6th Mercosul Biennial, 2007. Photo: Cristiano Sant’Anna

In line with Camnitzer’s suppositions, the Mercosul Biennial began to operate, from 2008 onwards, as a cultural project of continuous action with public actions every two years; and unintentionally, as a sort of free university with the sharing of non-institutionalized forms of knowledge as a goal. This element was reinforced by the education project of the 7th Biennial (2009), proposed by the then pedagogical curator, Argentine artist Marina De Caro.

This Biennial’s pedagogic program comprised a series of geographically decentralized actions – politically and culturally – such as: the Artist is Available Program6 comprising 12 artist residencies in different social, political, and cultural contexts: schools, public and private universities, museums, NGOs, social occupations, and youth projects in 22 cities throughout the Rio Grande do Sul state; and the project Practical Maps, which involved the mapping of already existing artistic and educational practices in Porto Alegre with a view to decentralizing the educational workshops and activities of the 7th Biennial.

De Caro believed that more importantly than offering workshops inside the Biennial and, thus conditioning the artistic experience of visitors to a project that only happens every two years, the Biennial should map and capitalize on the city’s existing creative opportunities, platforms and workshops calling attention to these practices, their educators and their methods.

Public Mediator Project. 7th Mercosul Biennial, 2009. Photo Eduardo Seidl

Another initiative De Caro proposed was the Public Mediator program, a pilot project that aimed to talk about the place of discourse’s production in and about art and that, in practice, was the opening of the mediation activity – up to that point only conducted by mediators trained by the Biennial – to any person who was interested in presenting and/or discussing one or more aspects of the exhibitions.7

Pedagogic Project: Practical Maps – Workshop Where is the art? With the artist Marcos Sari, by the Guaíba river. 7th Mercosul Biennial, 2009. Photo: Eduardo Seidl

In these projects – Artist is Available, Practical Maps and the Public Mediator – De Caro proposed a revision in power structures in relation to the production of knowledge generated by and with the Mercosul Biennial. In doing so, the pedagogical curator of the 7th Biennial reallocated the educational responsibility of the Mercosul Biennial, sharing it with different educators, artists and communities of Porto Alegre and the state of Rio Grande do Sul, further amplifying the concept of the micro-university proposed two years earlier by Luis Camnitzer.

Caro argued that the aesthetic experience, the politics and the education project proposed by the Biennale, should not only be linked to the discourse, time and space of curatorial proposals once every two years, but to truly engaging with initiatives, proposals and processes already brokered by the local community, that is, those who constitute the political, poetic and pedagogic body from which the Biennial itself emerges. With this idea the curator proposed to de-territorialize the Biennial of its “majoritarian” centralized notion of education8 – or of what Brazilian educator Paulo Freire called “banking education” where knowledge is seen as something to be deposited rather than engaged with – pulverizing it into countless micro-actions designed in partnership with different artists, educators, groups, and communities. Marina believed in the scale of “one to one” – in contradistinction to the focus on numbers of many educational projects at art biennials – in constructing an experimental micropolitics and in the openness of artists to be “available”. Interestingly, working in this way, she managed to organize a powerful network of interlocutors and collaborators who became fundamental to the artistic and educational projects of the following Biennial.

This shows that the transpedagogy put forward by Mexican artist and educator Pablo Helguera as a central concept of the education program of the 8th Biennial (2011), which at the time was seen as an innovative concept with respect to the interrelationships of art and education in contemporary society, was strictly speaking already present at the Mercosul Biennial through practices that had begun with the 6th edition and deepened in the 7th.9 If it had been otherwise, ‘transpedagogy’ would not have had the meaning that it did. It would probably have come and gone just like importation of a readymade idea and Casa M would never have managed to be as transformative as it was10.

Imagem 1: Casa M (façade). 8th Mercosul Biennial.

Imagem 2: Casa M. Tatiana da Rosa and Yanto Laitano duet. 8th Mercosul Biennial, 2011. Photo: Flávia de Quadros

At once an artistic platform and community center situated in an old renovated neighborhood house in the historic center of the city, Casa M (House/Home M) was that place outside of time and in time that opened and closed after the main Biennial exhibition. It welcomed the community of Porto Alegre and its neighborhood, mobilized a field of affections and exchanges, saw the birth of loves and marriages, gave its floor so that children could learn to walk, and served as laboratory, studio, auditorium, school, open kitchen, music studio, dormitory, community center, and playground. Yet “Casa”, proposed by Helguera and Jose Roca, respectively educational curator and chief curator of the 8th Biennial, was something to which the Mercosul Biennial (the transatlantic version) never understood or paid great attention.11

No poetic, political or pedagogical experience, throughout the in process trajectory of the Mercosul Biennial has been, up to the present day, as potent as Casa M. That “house/home”-platform was the place of “memorable life experiences”, as Jose Roca articulately stated about the potential of art biennials nowadays.12 That space was no longer curatorial, institutional, artistic, or educational; that place was a “commons”. And the Mercosul Biennial, paradoxically, did not fit there. But, apart from the contradictions, the Biennial was there in its most beautiful poetic, political, educational, and emotional formation – and it held much of Roca and Helguera, but also Luis Camnitzer, Marina De Caro and especially Carla Borba, Gabriela Silva, Gaston Santi Kremer, Fernanda Albuquerque, Sara Hartmann, Maíra Dietrich, Gabriel Bartz, Paula Luersen, Carina Levitan, Michele Zgiet, Estêvão Haeser, Maroni Klein, and much of Porto Alegre.13

That “casa”, so small that it ended up being huge, was both a problem and a hope in the conception of what education could be in the 9th Mercosul Biennial (2013). It was a problem because nothing could ever be so potent. A hope because, for having experienced it, there was a guarantee that other forces and formats – beyond artistic apparatuses and the art system – could also be part of that immense ocean liner called the Mercosul Biennial that had contributed to Porto Alegre for more than a decade. Here was a good place to begin.

Casa M (street). Workshop by the curator Paola Santoscoy. 8th Mercosul Biennial, 2011. Photo: Cristiano Sant’Anna.

One could say then, that the sense of the public in the Mercosul Biennial is related to what leaks and is leftover from the rigid structure of the Biennial itself, that which escapes strategic planning and institutional demands, that which flees the art world’s agendas and happens on sidewalks, the town square, the park, in the bars of Beach Street, beyond the Biennial’s timeframe, perimeters and exhibition spaces, in the public sphere. Its equation, therefore, is not accurate nor even contingent. It cannot be measured in numbers, miles, walls, exhibition spaces, national representations, concepts, works, artists, or visitors. The Biennial’s sense of the public’s engagement is measured by its ability to listen and, surprisingly also, by its ignorance in relation to these ideas and happenings. Institutional and community-based, transatlantic and homely, utopian and feasible – the Mercosul Biennial that I refer to here is, in this way, the sum of the 1st with the 2nd. Over four editions and in less than a decade, the Mercosul Biennial transformed itself into a project that installed the measure of its own meaning and that has, today, the size of its footprint, with the detail that this footprint is becoming more and more collective, gas-like and extra-institutional.

What this shows us is that the sense of publicness for the Mercosul Biennial is above all related to its own self-process of “de-education”; a process that shifted from the evangelical meaning that was proposed initially, but that, more than stemming from a provenance of a bi-annual curatorial project, a model that persisted for a few editions, was the sum of the many aspects seeded within and outside the institution since 1997.

Thus, when talking about the sense of the public or publicness for the Mercosul Biennial, rather than reflect on the affirmative and successful institutional steps taken in recent years as noted in the beginning of this essay, we must also touch upon its untested feasibilities – those processes, unknown yet somehow desired, that in their achievement carry out what had previously been the “untested” and the “unviable”. In the case of the Biennial, they are related to its understanding of what education could be. Materially, we mean seemingly ordinary movements, seldom remembered, places deemed to be of non-enunciation or secondary voices. It is about the unseen, what remains (and resists more!) when it comes into the public sphere not because it is of interest or because it was proposed as part of a project, but because it is inevitable.

This process began long before the curatorial intervention in the 6th Biennial; in fact, it appeared in its 1st edition – in an unconscious manner, but no less real – when the Mercosul Biennial organized its first training course for mediators (called monitors at the time or in other words people contracted to offer guided tours of an exhibition). Here, in this history, already set up and to which many were blind, was the training institution announced by Luis Camnitzer a decade later.

This Biennial, that the Mercosul Biennial still does not understand, was also inaugurated in 1997, it also wanted to counter and upend History (of art), although at that time it knew little or nothing of it. It was a story of voices considered minor, secondary, of multiple voices; it was a story of ignorance, empowerments and emancipations – of still untested, but feasible voices.

These were the voices that founded (and affected) the direction of education carried out in the 9th Mercosul Biennial. These are the voices that make up the Mercosul Biennial school that the Biennial still does not know exists. It was for and with these voices that the pedagogical project of the 9th Biennial was built. I refer here to a significant number of people who engaged in the Biennial as mediators over the course of its nine previous editions – students, teachers, the curious that today are artists, educators, parents, mothers, researchers, cultural managers, curators, mediators, workers, collaborators, and visitors.

If the Biennial can, today, be considered a school, it is directly related to these people and to what in the context of the institution had became known as the Mediator Training Course. With the 9th Biennial, we preferred to call it Cloud Formations, emphasizing connectivity and networks (social, cultural, educational, political, affective) and in keeping with the themes of the 9th Biennial, Weather Permitting.

Conceived originally as a primarily rear-guard action, the mediator course was not designed, in reality, for the mediators, but rather for guaranteed good public service to the public-spectator of the Biennial – that illustrious unknown, which biennials and other cultural institutions desperately attempt to attract with offers of “access”, “satisfaction”, “culture”, and “knowledge”.

In an unofficial sphere, however, the route taken was another one. Over the course of the program, the training of mediators exceeded the institution’s mode of measuring and became a kind of autonomous zone of knowledge production, of affections and narratives generating important and different ways of thinking and moving in the context of the Biennial and out of it too. The emergence and timeliness of ideas and proposals presented by the mediators began to form and guide the thinking of the Biennial’s education project as a whole, which worked to think about the training itself as the focus of its action of education, self-education and most of all de-education. This change manifested in efforts to shift preconceived notions both from the point of view of the chains that oppress the mediator figure in the context of art and its institutions; and from the point of view of oppressive and “moral values” that in general tend to underpin educational projects. This reached a point where even the education project found itself uncertain about the necessity of mediators in exhibitions, but never with regard to the training of mediators as core to the project, for in this lay the real meaning of what could be understood as education in the context of the Mercosul Biennial. The mediators saw themselves as citizen critics, and in this way the course seemed much more potent than one of training translators of a pre-established discourse.

Thus, the training of mediators gradually ceased to be a course aimed at providing a service and instead became the educational project of the Mercosul Biennial – political, poetic, educational, emotional, and processual – that could be seen mainly in the 8th and 9th editions with a series of artistic and pedagogical interventions proposed by mediators, such as: performances, open dialogues with the public without any “institutional mediation”, actions on the street, hikes, and evening parties, among others. The concept of mediation as a portal of satisfaction “guaranteeing” the public access to so-called obscure cultural codes gave way to an idea of mediation that was above all a poetic-critical deconstruction of mediation and the mediator and, consequently, the conception of the public, education and institution. Affirmative and salvationist education thus gave way to a critical education: irregular and uncertain.

Nocturnal Perambulations. 8th Mercosul Biennial. Photo: Maroni Klein

At the 8th Biennial this can be seen through the experience of Casa M, where mediators were the coordinators of their own work, acting as artists, educators and critics at the same time. The Nocturnal Wanderings project, which consisted of mediation-walk-parties proposed by the mediator and supervisor Maroni Klein and her team of mediators, as well as by other educators and producers active in the 8th edition, was carried out in the center of Porto Alegre in order to discuss the city’s physical body and the emotional reverberations of one of the Biennial’s exhibitions comprising public art commissions dispersed throughout the city center, called City Unseen. In Nomadic Mediations, which consisted of open-ended dialogic “wanderings”, itineraries opened to the public weaving in and out of various exhibitions of the 8th Biennial, mediators proposed new curatorial readings of the exhibition project, bringing new references and suggesting new directions and other initiatives.

Cloud Formations. Field talks. 9th Mercosul Biennial, 2013. Photo Eduardo Seidl

Cloud Formations. Field talks. 9th Mercosul Biennial

The 9th Biennial’s pedagogical project Cloud Formations14 comprised the creation of an integrated network of training for mediators, educators and the curious general public and was characterized by the decentralization of power related to knowledge production, not only theoretical discourse, but fundamentally political and poetic sensibilities of the modes of speech and the artistic and educational practices with which that Biennial was engaged. In so doing, the 9th Biennial’s education project represented a turnaround in the structure of what had been up to that point understood as education in the context of the Mercosul Biennial. Throughout the event the mediators proposed an endless series of investigations, interventions and poetic propositions, some highlights of which are: Transmediations, comprising mediations that proposed a dialogue about transversal cultural themes and transgendered issues via the cross-dressing of the mediators involved; Flight Mediators, featuring artistic pedagogic interventions performed in alternative spaces, the street, the town square, but mainly within the exhibition spaces of the 9th Biennial; the Escola Caseira de Inventions (Home School of Inventions)15, run by two educators and a group of mediators, engaging the daily collaboration of active and disorderly artist “residents” and school visitors; and especially the critique that the mediators made publicly to the Biennial.

Transmediations. 9th Mercosul Biennial – Porto Alegre, RS, 2013. Photo: Tarlis Schneider

Home school of inventions – Introductory workshop about Arduino. 9th Mercosul Biennial – Porto Alegre, RS, 2013. Photo: Guilherme Dias

By creating in 1997 the training of mediators as one of its central actions, the institution involuntarily exposed the loopholes within itself, which started a long road that, for it to be truly traveled, meant that it could ultimately not belong to the Biennial. A path moving towards a minor education16 – an education that at institutional levels called into question the relationship between success and failure, which only appeared when something bothered its protagonists, when something was not met or didn’t meet expectations.

Rio de Gente (river of people) parade, Porto Alegre, RS. 9th Mercosul Biennial, 2013. Photo: Tarlis Schneider

A minor education is a parallel education, underground, agonistic and unpredictable. It occurs within micropolitics, direct daily action, affective relations, the de-institutionalization of life, in confrontation, and in the space that we want to be common. It is therefore a venture of resistance, as Brazilian educator and researcher Silvio Gallo notes, “against the established flows, […] imposed policies […] A minor education is an act of singularization and militancy”17. It is unquantifiable.

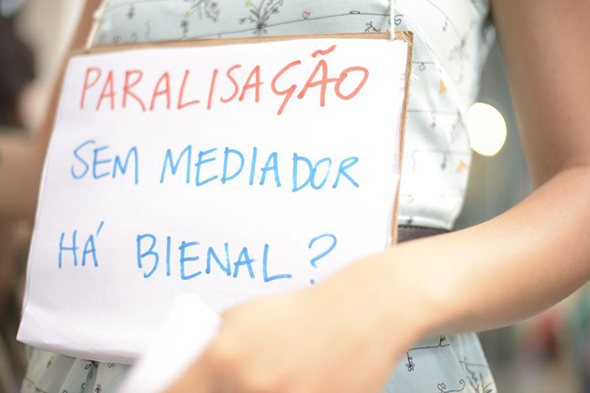

A minor education was what came screaming to the Mercosul Biennial in October and November 2013 during its 9th edition. It came at a time when the country was also experiencing an intense process of awareness, faced with the very question of what the public means. This minor education spoke through voices, institutionally perceived as secondary, those usually only allowed subaltern narratives, the Biennial mediators; those who in reality were its first public, those who arrived before and left after, who most intensely lived the relationship between the Biennial and the city, those who became educators and, often, returned to the Biennial with their students and families. When they were critical, they faced it with their most valuable asset: they questioned and tested the Biennial’s relation with (what it understood as) the public and their educational mission via a series of protests in and out of the Biennial, where they requested answers and explanations from the institution regarding some practices they understood to display irresponsible attitudes, social discrimination and situations of bullying.

Mediator’s protest. 9th Mercosul Biennial. Photo: Bernardo Jardim Ribeiro/Sul21

In a complex equation, education became undisciplined, running up against its own guidelines, and in doing so it became independent of possible outcomes by the very simple act practiced. It configured itself as education in its fullest measure. This was, of course, and is to the present day, the greatest achievement of the Mercosul Biennial: over the years, the Biennial formed itself in such a way that its education project – its most precious asset, as already mentioned – became its greatest critic.

During its 9th edition, the becoming of the Biennial in the public sphere and the public sphere of the Biennial, which “had been in the air” since 2007, finally was understood. It became the critical thinking that Luis Camnitzer had defended and that the very institution had tried to incorporate as its “mission” since then. However, with this mission accomplished, the Biennial, not knowing what to do with it, silenced it and opted for a “majoritarian” education.

“Who do these people think they are?” “They do not know what they are talking about!” were just two of the many comments that flooded the corridors of the Mercosul Biennial, local newspapers, social networks, and the city of Porto Alegre for weeks. Those people did not think they were, they already were, and had been, simply and directly, requesting that the Biennial listen. They were, perhaps unintentionally, emancipated from a project that from that time onwards no longer belonged to the institution. It was more than ever in the fabric of the city, in the narratives of its community, in public debate, in the large and organic autonomous zone of life. The Biennial finally had become a school.

Here it is, what Oswald de Andrade voiced in the Brazilwood Manifesto as the main “millionaire contribution of all the errors”18 of the Mercosul Biennial: to have become in a project that is only what it is because there it no longer fits within the Biennial. This equation is due to the curious combination of institutional restrictions and its incapacity to lead with the curatorial propositions, affective exchanges and political, social and cultural demands arising from the different meanings of the public that make up the Biennial.

“The way we speak. The way we are.”19

_

1 The Southern Common Market, or Mercosul or Mercosur (in Spanish) consists of an economic bloc created from the Treaty of Asuncion in 1991 in order to facilitate the free movement of goods and services between member countries (Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Paraguay and Venezuela), in addition to establishing a kind of common external tariff that standardizes product prices for those countries for export and foreign trade. However, being an economic agreement, the focus was primarily financial and political, and cultural issues were completely set aside. It is in this regard that its effectiveness is questioned in the comment above, in the sense of a real integration between the countries so as to generate the common good for its citizens.

2 I do not refer to or include the 10th edition of the Mercosul Biennial in this essay, since it will take place throughout the year 2015 and is currently still in the development phase.

3 Mônica Hoff and Dominic Willsdon. “City as Curriculum: The 9th Mercosul Biennial.”(Accessed February 2015)

4 The title and function of the education curator were employed starting from the 6th and continuing to the 9th edition of the Mercosul Biennial. The 10th Biennial to be held in 2015, the chief curator and the institution elected not to use this nomenclature, returning to use the term educational coordinator, or coordinator of the educational project.

5 Luis Camnitzer. “Proposta para el aspecto pedagógico de la Bienal del Mercosur.” 2007.

6 The central proposal of the Artist is Available Program was working with art projects that contained strong educational capital, i.e., projects and practices already made by artists in art contexts that as artistic methodologies could potentially be experienced in other contexts. Twelve projects were carried out in 22 cities in 9 different regions of the state of Rio Grande do Sul. The project development, reports and participant statements can be accessed in the publication Micropolis Experimental, published by the pedagogical project of the 7th Mercosul Biennial in 2009. See de Caro, Marina. “Micropolis Experimental: translations of art for education.” Micropolis Experimental. Porto Alegre, 7th Mercosul Biennial, 2009

7 In all, there were six mediations from perspectives outside of the Biennial itself and each addressing the 7th Biennial from a specific point of view. One example is the mediation made by a seamstress who produced the huge curtains for one of the exhibitions who spoke of spending days working in solitude in the empty warehouse where the exhibition was presented, producing huge black curtains for something that she was not sure would be up until the moment she visited the exhibition as part of the Public Mediator project; or the mediation of a single work of the 7th Biennial by the artist Nicolas Floch that was presented by one of the exhibition guards of the Biennial; or the mediation presented by a biology teacher exploring the work of the artist Walmor Correa who was quite intrigued by the scientific theories that formed the basis for the artist’s work. The Public Mediator action formed the basis for much of the thinking about education and mediation of art proposed in the 9th Mercosul Biennial, four years later.

8 I refer here to the ideas proposed by the educator and researcher Silvio Gallo about the meaning and place of education. The author proposes, based on the thoughts of Kafka, Deleuze and Guattari, that we think about a minor education, one which is guided by everyday life, not only in the school context, but the social, cultural, and economic life of its educators and students. An education that goes beyond education policies, offices and departments. An education as a practice of freedom, as Paulo Freire proposed. An education as “a militant enterprise.” Silvio Gallo. “Em torno de uma educação menor.” Educação & Realidade. jul/dez, 2002. p. 169-178. (Accessed February 2015)

9 The term “transpedagogy”, created by Pablo Helguera, was the basis for the design of the education program of the 8th Mercosul Biennial. Helguera uses it to refer to projects created by artists and collectives that mix educational processes and art making in ways that offer an experience that is clearly different from conventional art academies or formal art education. Pablo Helguera. Education for Socially Engaged Art. New York: Jorge Pinto Books, 2011. p.77.

10 Casa M (Literally House M or Home M (the M taken from the M of Mercosul) was designed by Helguera and Roca as an activating strategy for the 8th Mercosul Biennial, opening four months before the official Biennial exhibition (in May 2011) and closing one month afterwards (in December 2011). It was originally proposed as a potentially permanent initiative to be incorporated by the Mercosul Biennial Foundation continuing its work within the local context, not just focusing on the bi-annual exhibition. However, based on financial issues the institution rejected this proposal.

11 I refer here to the effect Casa M generated in the community of Porto Alegre. Its power as a community and educational art space was perceived in the actions undertaken by the local art community, the educational practice of the Biennial, in the vicinity of the neighborhood where Casa M was located. This was evident in the campaign “Stay Casa M”, created by the mediators of the 8th Biennial in collaboration with local artists, educators, and the Casa’s neighbors and made to the management of the Mercosul Biennial Foundation to request that Casa M become permanent as a cultural facility of the Biennial in the city. The institution, motivated by financial issues, denied the request.

12 According to Jose Roca, chief curator of the 8th Mercosul Biennial, in his Duodecálogo “exhibitions are held in order to have memorable life experiences”. The Duodecálogo is a kind of declaration of principles about the craft of curatorship and the biennial model proposed by Roca and published in the 8th Biennial catalogue. Also in the training handbook for mediators. See Pablo Helguera. Mediation – traçando o território. Porto Alegre: Mercosul Foundation Visual Arts, 2011. p. 111-113

13 See statements from mediators, artists, curators, educators, and Casa M neighbors and visitors. In: Pablo Helguera and Mônica Hoff. Pedagogia no campo expandido. Porto Alegre: Fundação Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul, 2011

14 Cloud Formations was a kind of informal education and integrated platform for public and diverse agents interconnected ontologically – mediators, educators and a curious public – that, in practice, are often understood as distant publics. The program lasted eight months – from May to November 2013 – starting before the Biennial opening and ending with the closing of the exhibition. It was designed to generate a training program that integrates different publics in ways that were horizontal, critical, and non-instrumentalizing, creating and forming itself as a large network of encounters and discussions that were decentralized and fully integrated with each other, so that this “network” could simultaneously work as the mediator for the 9th Biennial. To enable this network training, the program was structured in two interconnected networks: one network focused on activities carried out at local and regional level – called the Land Network – and the other focused on activities at the national and international level – called Cloud Network. Among the activities were: transdisciplinary public lectures with the participation of artists, curators, mediators, educators, and researchers; mediation labs, comprising theoretical and practice-based encounters in different places throughout the city of Porto Alegre – auditoriums, public parks, botanical gardens, parks, on the street and also via the internet – focusing on the collective construction and critical sense of mediation in art, education and in everyday political practice; residences for mediators in schools, research laboratories, community centers, cultural institutions and family farming, recycling and bio-architecture cooperatives aimed at exploring forms of inexact and irregular kinds of knowledge via inter-, multi- and transdisciplinary dialogues; as well as projects called “Field Conversations” and “Tides”. The first consisted of a series of study trips to different parts of the state in order to decentralize the 9th Biennial not only spatially, but also conceptually, leaving the narrow field of art to understand how processes generated in other fields could also move and affect people, generating fundamental questions for art and its ways of being. This activity also aimed to reverse the logic presented in the latest editions of the Mercosul Biennial, in which the project was heading to inner cities taking their methods and technologies in order to ‘train’ educators from other communities. At the 9th Biennial, the intention was the opposite: to bring people from the capital and metropolitan region to meet and learn from other communities. The second project, “Tides”, could be considered both as an artistic commission conceived by the three artists-educators and as a laboratory, coordinated by these artists, focused on dialogue and the shared construction of the meanings of art and education with educators from 15 cities in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. Finally, as part of the Cloud Formations program, I should also mention the International Symposium: Someone Who Knows Something…and Someone Who Knows Something Else: Education as Encounter and Equality curated by Domnic Willsdon and Mônica Hoff. The symposium generated a public debate focusing on the places of knowledge production and the production of discourse. It happened simultaneously in 20 different spaces (schools, museums, town squares, studios, gardens, café shops, bus stations etc) throughout the city of Porto Alegre, and then brought all participants together for an open conversation presented in the ground level gallery of the Museum of Art, Rio Grande do Sul, also one of the exhibition spaces of the 9th Biennial. For more about the symposium.

15 The Escola Caseira de Invenções (Home School of Inventions) was a mixture between an office, an inventions workshop, a laboratory, and a library. It was an artistic commission proposed by the 9th Biennial ground curator (term used for the pedagogical curator in the 9th biennial in keeping with the ecological and climate themes – other curators on the team assumed similar titles such as “cloud curator”, etc). Made in collaboration with two educators and a group of the 9th Biennial mediators, the commission aimed to create a pilot project to discuss with teachers, students and visiting public the meaning of school. What it is, what it should be, and what is meant by the term school, and whether to identify this project as a school. Over the 59 days of exhibitions many people visited the place and participated and offered informal activities, discussions, research, conversations, improvised seminars, planted some spices, made huge soap bubbles, made test bands, performed workshops, or just sat a little to rest. Three artists of the 9th Biennial – James Rivaldo, Leticia Ramos and Leonardo Remor – participated in the creation of the school and engaged in ongoing work and research as artist residents.

16 Op cit., Gallo. p. 169-178.

17 Ibid.

18 An expression taken from the Manifesto of Pau-Brasil (Brazilwood) Poetry, published by Oswald Andrade in 1925. That manifesto is the first in a series of manifestos that were responsible for presenting the aesthetic notions that came to guide modernist artistic and poetic production in Brazil, deeply informed by Andrade’s notions of anthropophagy (cannibalism) – a metaphorical and symbolical “eating” and “re-formulation” of other European and colonial cultural forms and practices. By writing: “Language without archaisms, without erudition. Natural and neological. The millionaire contribution of all the errors. The way we speak. The way we are”, Andrade was telling us of the many errors and deviations that make up the “formation/training” which constitutes and characterizes us. In the context of this essay, it serves as a metaphor for the meaning of education constructed throughout the Biennial’s trajectory. See Oswald de Andrade. “Manifesto da Poesia Pau-brasil.” In: ANDRADE, Oswald. A utopia antropofágica. São Paulo: Globo, 2011, p. 59-66. English translation Stella M.de Sá Rego. Latin American Literary Review, Vol 14, No.26, Brazilian Literature (Jan – Jun 1986) pp 184-187, p.185. (Accessed March 2015)

19 Ibid.