Regional encounter: Publicness in Art: Crabs & Butterflies. Casa Daros, September 28th, 2013. Photo: Delmar Mavignier

“Insertions”: Multitudes in the Metropolises and… our Museums

Barbara Szaniecki

1. Crabs and Butterflies, Wasps and Orchids and Much More…

In September 2013 the first in the series of encounters, Publicness in Art, was held at Casa Daros, Rio de Janeiro, bringing together a “representative” group that drew on diverse fields of knowledge and art practices.1 Prior to the meeting, the organizers had emailed participants an instigative image by way of a provocation:

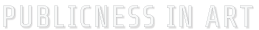

Crabs & Butterflies – A Poetic Reference. Ancient Roman coins featured an image of a crab holding a butterfly, interpreted by researchers as moral of “festina lente” or careful advance. The convergence of delicacy and strength in this nearly impossible juxtaposition could refer cryptically to the recent presence on the streets of Brazil – between the lightness of youth and the threatening force of the police. Inspired by these events and Casa Daros’ commitment to the transformation of education and art, we propose a de-acceleration of time and a political advancement in order to explore new possibilities for the re-signification of the meaning of the public in art. The image of the crab and butterfly (attached) will guide our meeting as an enigmatic juxtaposition. We invite each participant to bring to the meeting a reference (poetry, text, artwork, or other suggested connection) inspired by this image.”

Selection of prints and typographic water marks featuring the image of a crab holding a butterfly: G.Symenoi. Le sentiose imprese, Lyons, Rouillé, 1561; Jehan Frellon, Silvestre, Marques typographiques, I, Nº193 and Nº 400; Jacopo da Strada and Thomas Guérin, 1553, ibid No 454. Design: Taisa Moreno for the encounter Publicness in Art: Crabs & Butterflies, Casa Daros 2013.

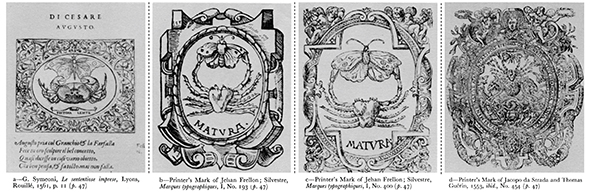

Crabs and Butterflies: the image visibly inspired the first exchanges between participants who gathered together in small groups. Interpretations of the image varied, at once revolving around a range of dichotomies and also the dichotomies’ deconstruction. The supposed opposition between the tough (crab) and fragile (butterfly), between the force of the police and the lightness of youth on the streets, among other oppositions, gradually gave way to the realization that these boundaries were permeable and that the dichotomy did not hold. Perhaps this spirit of deconstruction was prompted, when, at some point the son of one of the participants began to circulate among the various gathered groups with his drawing of a “Borborejo” – a neologism coined by one of the groups using the words caranguejo (crab) and borboleta (butterfly) suggesting the hybrid image that the drawing depicted. It seems that in its circulation, this hybrid creature contributed to the shift in perception of what was at stake in the image minted on the Roman coin.

Borborejo. Drawing made by the son of one of the participants in the encounter

creating a hybrid between a crab (caranguejos) and butterfly (borboleta). Photo: Barbara Szaniecki.

The crab and the butterfly are not necessarily two separate beings distinct from each other, but rather, entities undergoing continuous alterations blurring any possibility of a distinct “being” that is not continuously changing its form: transformation. From the image of self versus the other emerged the very image of change itself (otherness in action). The circulation of the image provoked our senses and, this movement in circles, generated other meanings for the image itself.

It was not surprising that at various moments during the meeting Cildo Meireles’ public art interventionist works Inserções em circuitos ideológicos (Insertions in ideological circuits) came up together with a subsequent text, published in 1981, in which the artist discusses these interventions, in particular his Projeto Cédula (Banknote Project).2 Just as the circulation of the “Borborejo” could be seen to affect the meaning of the crab and butterfly image, the circulation in the 1960s/70s of banknotes with the inscription “Who killed Herzog?” affected the official interpretation of the journalist’s disappearance, a gesture that returned again in 2013 when banknotes were transformed with the inscription of “Where’s Amarildo?”3

Cildo Meireles. Who Killed Herzog? 1976 Photo: Pat Kilgore

Cildo Meireles. Where’s Amarildo? 2014. Photo: Pat Kilgore

The “Crab and Butterfly” was engraved on a Roman coin. “Who killed Herzog?”4 and “Where’s Amarildo?”5 were printed by Meireles on banknotes of a cruzeiro (old Brazilian currency) and two real bills (current Brazilian currency) respectively. In addition to new meanings, can new circuits and circulations promote new material and immaterial values? Meireles mentions the control under which the press, radio and television operated and how he set out to find other “ideological circuits”. I suggest as other “ideological circuits” the metropolises and social networks as spaces where it is possible to re-signify and build other values… material values and intangible values.

Butterflies and crabs minted on coins. Questions without answers stamped on Meireles’ banknotes. For him, “the important thing in the project (Banknote) was the introduction of the concept of ‘circuit’, isolating it and fixing it. […] In fact, the character of ‘integration’ in this circuit would always be one of counter-information”. Here art consists of the courage to put into circulation information that places tension on the absolute and authoritative truth that characterizes our system and information society.

Wasps and Orchids: let us return to the issue of circuits and circulation. From the image of the crab and the butterfly to another image, an immediate association I made, to that of the wasp and the orchid that Deleuze and Guattari use to speak of becoming.

The wasp and the orchid provide the example. The orchid seems to form a wasp image, but in fact there is a wasp-becoming of the orchid, an orchid-becoming of the wasp, a double capture since “what” each becomes changes no less than “that which” becomes. The wasp becomes part of the orchid’s reproductive apparatus at the same time as the orchid becomes the sexual organ of the wasp. One and the same becoming, a single bloc of becoming, […] an “a-parallel evolution of two beings who have nothing whatsoever to do with one another.”

Gilles Deleuze and Clare Parnet, Dialogues6

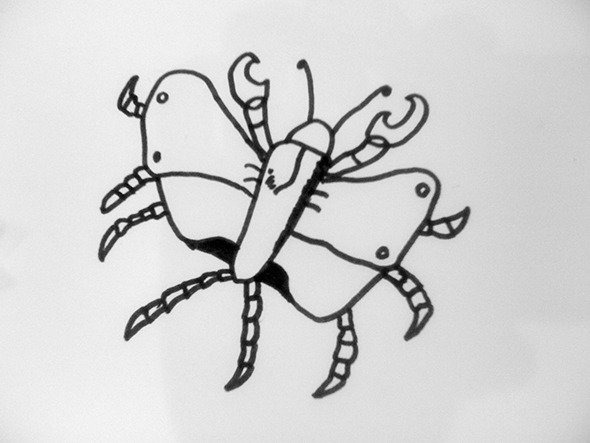

A wasp and an orchid occupy the top right-hand corner of an image in the book Fadaiat – Libertad de Movimiento/Libertad de Conocimiento (Fadaiat – Freedom of Movement/Freedom of Knowledge), edited by collectives fighting against state oppression and for immigrant rights in the region near the Straits of Gibraltar, which separates Africa from Europe.7 In this highly controlled area, communication between Tangiers (Morocco) and Tarifa (Spain) was realized by means of an artist-militant-hacker triangulation. By combining the design of the wasp and orchid with the artist-militant-hacker triangulation, the collectives were clearly invoking a theoretical reference to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari.

Fadaiat. Diagram, 2006

The image from the Fadaiat book presents two lines: a “local versus global” line (which is necessary to analyze from a specific location such as the city of Rio de Janeiro, versus a global context, which is the marketplace of large cities) and the line “analog versus digital”, which also does not come to a synthesis, but rather folds out into another line, where the purely technical gains space-time dimension that in turn becomes the line of “territory versus network”.

In the meshing and tension of these lines, it is the artist-militant-hacker triangulation that provokes the process of becoming an emancipatory power, in this case the freedom of movement and knowledge against the boundaries that oppress them. For this power to unfold, the premise is that the “artistic”, regarded by many as the exclusive domain of artists, merges with “activism” and “hackerism”. This expanded or generalized artisticness (“general artisticity”8) creates a new line of non-dialectical tension: the line “multitude versus institution”. There is no dialectic, that is, there is no promise of synthesis to eliminate the conflict, but rather the possibility of a becoming that is not common to both: an asymmetric “a-parallel evolution”.

Next, I propose we think about the artistic institution par excellence – the museum – as that which exists between territory and network (i.e., as a result of the lines “local versus global” and “analog versus digital”) to, later on, from this new configuration, reflect on institutions seizing a new relationship with the public in these times of “insertions” of the multitude in streets and networks…

2. Museum, Territory and Network

The museum today remains anchored in the notion of territory – as a temple of Art, space of artistic experimentation or place of memory and sociocultural experience. Sometimes it is all this mixed up together. At the same time, the museum today is also active, involved in and an engaged catalyst of diverse networks. It can take the form of an artistic network-company primed for capturing and producing patrimonies spanning the entire metropolis, a global network-corporation whose headquarters and subsidiaries produce and reproduce products and brands of artists, or even modes of resistance to these devices of capture. And, again, it is all this mixed together.

Today, every museum inserts itself in a unique way in technological but also sociocultural, economic and political terms, in the analog versus digital and local versus global lines. Museums simultaneously or alternately assert themselves as “territory” and “network” in numerous ways and in different combinations of forms, but they all intersect with the new phase of capitalism that has been defined as creative.

At the heart of creative capitalism, the museum also acquires new functions: in global terms, via its architectural and symbolic monumentality, the museum (and other sporting and cultural mega-structures that participate not only in global mega-events that are temporary, but also in the ongoing “creativization” of cities) strives to insert the city in which they are located within the global market of tourism and consumption of cities worldwide. In local terms, via their territorial and community relations, the museum is asked to participate in urban revitalization articulating creative clusters (geographic concentrations of companies in the creative sector, but not only) and cultural communities in areas considered by the government as rundown.

These two functions can be seen at work in the port area of Rio de Janeiro, although they are certainly not exclusive to this region of the city. The museums in place there are: the first and recently inaugurated Museum of Art of Rio de Janeiro (MAR) and the second, under construction, is the Museum of Tomorrow. Both seek to effectively insert Rio de Janeiro into the global cultural-creative circuit while stimulating local development of clusters, voluntarily or involuntarily contributing to processes that, depending on their management, can initiate “revitalization” or, conversely, “gentrification”. In other words, the construction of these new cultural facilities is at the expense of the maintenance of existing ones, and, above all, the attraction of the “creative class” to the detriment of the local population, which is under threat of eviction.9

These functions can of course be assumed uncritically or, conversely, be problematized collectively. Creative-cultural spectacularization, real estate speculation, local development, and urban regeneration are not new phenomena, but rather they indicate a new cycle within which institutions and artistic movements are operating and, as such, need to be critically conscious of, so that they can position themselves to act with consequence.

Amidst creative capitalism and troubled times, Rio de Janeiro is able to especially take advantage of heterogeneous artistic institutions, where the “artistic” itself acquires a broad sense: historical museums, museums of the modern, even ultra modern era (including art) and contemporary museums (also including art). Each in its historical period marked a territory: the city center as the catalyst for urbanity in the case of the first museums, the Aterro of Flamengo (reclaimed harbor land) that paved the way for modernity in the case of the second, and rundown city center areas, as well as peripheries in the case of third. The city also has museums that present themselves as being “traditional” and “community-based” to the extent that they maintain strong links with their immediate socio-cultural environment and museums that define themselves as “new”, where the new, in many cases, is associated with new technologies and global issues. As I said earlier, most museums navigate these different aspects in their own particular manner, and, in the same geographic context different museum experiences coexist.

The port area, for example, comprises such diverse museums as: MAR (Museum of Art of Rio de Janeiro), Casa Amarela da Providência (Yellow House of Providence), Instituto de Pesquisa e Memória Pretos Novos (“New Black” Institute of Research and Memory focusing on the legacy of slavery see translators note10) and Condomínio Cultural (Cultural House), with goals and desires that sometimes converge and sometimes diverge. The Maré favela features the Museu da Maré (Maré community history museum) and Galpão Bela Maré (Beautiful Warehouse of Maré – contemporary art and cultural center). It’s not only the museum experiences that are different from one another, but also what might be realized between them. And, even though almost all of them have ineffectual digital platforms, almost all seek an “outside” of the museum – the “outside” presented in Hélio Oiticica’s assertion that the “museum is the world”, or in Meireles’ search for a circuit beyond “consensual, consecrated, sacred space”.

The museum seems to have become polymorphic11 or monstrous.12 If the proliferation of new museums confirms the entrance of Rio de Janeiro into a global city marketplace – today all cities, everything from global capital to individual tourism, “are purchased” at a global business counter – this market presence finds much resistance. Resistances that constitute themselves in the dispute of what is meant today by the notion of “the public”.

And here, the image of the wasp and the orchid makes sense. One belongs to the animal kingdom, the other to the plant kingdom. And yet, something (unnatural) occurs “between” them and out of each other’s reach. The crisis of political representation is on par with that of the crisis of museum mediation, one that implies the need to rethink the relationship between the institution and the art system as this public “other” in completely different terms. This is not necessarily the artist-militant-hacker agency presented in the Fadaiat book but it is a representation of all who want to invent. June 201313 opened a plethora of creative possibilities, and it certainly productively affected the meeting Publicness in Art…

3. Museum, Public and Multitude

Rio de Janeiro museums establish different relationships within their respective territories and networks, creating different spaces and temporalities: Rio de Janeiro is modern, postmodern and alter-modern at the same time. In this complex context, the notion of the “public”, both in the sense of citizenship space and in the sense of the receptive subject of artistic works seems to have taken on an overly modern connotation. In spatial terms, “public” may sound completely foreign in territories where everything is both public and private at the same time, that is, where we all are observers and observed at the same time. In post-Fordist times, “public” can also sound strange in sociocultural environments and production systems where everyone is producer and consumer at the same time. It is in this sense that the notion of “public” seems to be too “stuck” to the modern in a city where different spatiality and temporality coexist, as well as various interrelationships between them.

The issue of the “public” in art discourses resembles questions of the “masses” in the economy and the “people” in politics. These issues are not equivalent, but when confronted with each other, they may generate advances starting with the problems they have in common. Political institutions have not listened to the streets and have been unable to overcome the crisis of representation, that is, to open a political desire that exceeds or does not fit into representation models. Will artistic institutions be able to overcome the crisis of mediation, that is, to open themselves up to a desire for an art that exceeds or does not fit into current curatorial, critical and artistic practices?

The question of the public permeated the small group discussions of the meeting Publicness in Art. The notion of “forming publics” with its connotations of “training” is generally criticized either in terms of education or the market.

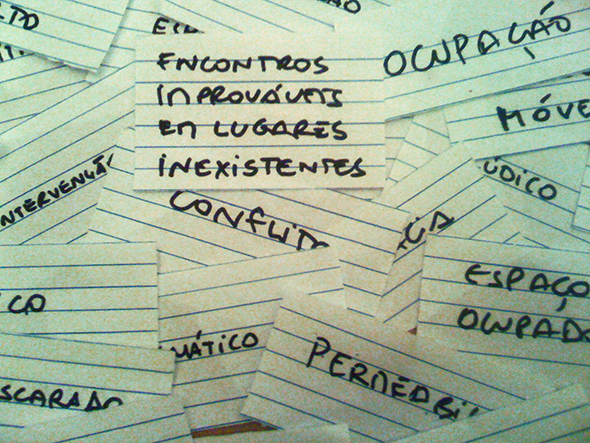

Words and phrases generated at the encounter Publicness in Art:

Crabs & Butterflies, 2013, Casa Daros. Photo: Barbara Szaniecki

From the vantage point of education, instead of notions of “forming publics”, critics rather argue for the promotion of artistic-pedagogic experiences that respect and do not systematically create hierarchies of knowledge or of the multiple subjects present in society. The museum welcomes other institutions and engages with other institutions in a dialogic relationship. From the vantage of the market, criticism manifests itself in a more ambiguous way: on the one hand, we question a system that can lay off or fire directors for not attracting sufficient publics, a system that operates within a rationality that favors competition at the expense of collaboration between institutions and that privileges consumption at the expense of artistic experience and criticality; on the other hand, there is a certain admiration for directors who can attract publics within the emergent context of a “new middle class”. The working class is no longer only a producer for the elite and middle classes, but its members are also becoming consumers of a wide range of products and services and, in turn, offering themselves as potential audiences for art institutions. After all, why can they not also benefit from these “public” institutional spaces?

The demonstrations in June 2013 surprised everyone. In these, young people (but not only) who had benefited from innovative public policies over the last twelve years expressed their desires for a life that was not limited to employment and consumption, in other words, not limited to the notion of “inclusion” that the connotation often conjures in terms of an emerging middle class. They wanted something more. They certainly wanted to go to museums, attend exhibitions and also buy works in the expanded network of galleries and art fairs. Why not? But also, perhaps they wanted, beyond learning about artistic experiences of the past and present or engaging in a dialogue with the art world (artists, critics, curators, etc.), to perform their own experiences within and outside the institutions.

This is undoubtedly a major challenge for art institutions. Some institutions choose to work as companies of “cultural and creative capitalism”, setting themselves up as local agents of a global city marketplace vying for international visibility through monumentality – of which a signature architectural presence is a part. Others, even though defined as non-governmental, opt for something like a “partial state relationship”, and are also cultural and creative, actively seeking sponsorship money and applying for state grants. Other formulas also exist. A few institutions have ventured to risk engaging with the autonomous and self-management practices of social and cultural movements, creating instances not only of pedagogy, but above all, co-research and co-creation between institution and collective movements.14

Perhaps it is within these space-times, even if ephemeral, where the museum and multitude can find modes of agency. But there is no denying that in the last year, it has been in the social networks and on the streets of the metropolis that the most potent forms of cultural experimentation have taken place. Is it art? If we consider art as an expression of potency, we can say certainly yes.

Many collectives formed online and on the streets innovating new expressive formats. They also experimented with more autonomous forms of organizing the production of art, culture and communication, with and without success. This self-organization may also indicate directions for new forms of artistic institutions: a self-producing institution (or self institutionalizing?) that re-means the “public”, in terms of space, or in terms of subjects and subjectivities that participate in artistic activities.

3. “Insertions” Multitudes in the Metropolises and… our Museums

We saw earlier that, during the military dictatorship, Cildo Meireles launched his Banknote Project and on a cruzeiro banknote stamped the words “Who Killed Herzog?”. When in June 2013 street demonstrations broke out with claims relating to the quality of life in the city and also with complaints about violence of the UPPs (Police Pacifying Units)15, Meireles did not hesitate and, on a two real banknote, stamped “Where’s Amarildo?”.

Cildo Meireles. Where’s Amarildo? 2014. Photo: Pat Kilgore

In these neo-developmentalist times, employment has increased, consumption has increased, GDP has increased… so what after all did the multitude that took to the streets want? It is impossible to grasp the totality of that desire. In a context of neo-developmentalism with strong industrial dimensions and leveraged by a kind of state capitalism, what Meireles proposed in the 60/70s is still valid: it is possible to seize:

[…] an opposition between consciousness (insertion) and anesthesia (circuit), considering the insertion as function of art and anesthesia as a function of industry. For every industrial circuit is usually large, but is also alienating.”16

Today the ideological circuit is not restricted to the press, radio and television mentioned by Meireles, but it also extends itself into the streets and networks that make up a vast metropolis, both real and virtual.

Meireles speaks of the necessity of anonymity to act within and against a logic based on different mystiques: “the mystique of the work itself (presentation, the screen, etc.); the author’s mystique (Salvador Dalí or Andy Warhol, by contrast, are current examples); or the mystique of the market (the game of ownership: exchange value).”17 The artist then proposed “insertions” to move beyond distinctions between who can and cannot do art, as well as an individual authorship that is always related to ownership, toward above all, something that “exists only to the extent that other people practice it”.

Through “insertions”, one loses both control and ownership of what is produced, and this loss is extremely productive. In this movement, “insertions” can reach more people, “to the extent that you do not need to go to the information, because information comes to you; and, consequently, has the ability to ‘explode’ the notion of sacred space”. There is little that remains here of the idea of “forming publics”. We are in a more direct and more open process where it is possible to learn via recent events. Online, the banknote page18 opened space to post banknotes with inscriptions of all sorts: “You cannot find happiness in banknotes”; “when money ends, friendships end”; “the worst poverty is that of the spirit of money”; and “how much did you sell yourself for today?” are some of them.

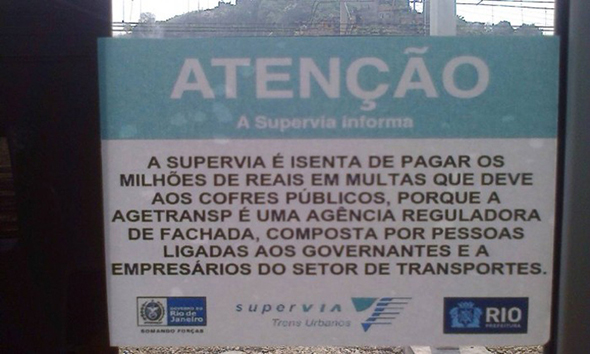

On the streets, or better yet, on the trains and stations of the Supervia (regional train system), a mysterious poster emerged recently19: “at peak times, you may need to let other people sit on your lap”. Supervia and the mainstream media denounced the poster and the police began a search for the anonymous author.

Public intervention in the Rio de Janeiro train system (Supervia – Trans Urbanos), 2013.

And what did passengers think of it? News features of the column “O Dia” (Today) mentioned the Facebook page “SuperVia – Shame on the Cariocas”20 where many praised the initiative of the unknown poster artist: “Supervia YES should take up action for those who depend on trains, not against those who in a creative and thoughtful way are protesting about how everyone is treated”. As the debate continued, a new sign appeared that said Supervia did not pay their fines.21

These two examples show how much Meireles’ proposal is current and in tune with the subjects and subjectivities who have demonstrated on the streets and online for months since June 2013. Let us remember that it all started with a movement launched by MPL (Movimento Passe Livre/Free Pass Movement) against the 20 cent increase in bus tickets. Far beyond 20 cents, the demonstrations expanded the struggle for mobility to a multitude of urban issues.

We can then, drawing on Meireles’ words, consider the street demonstrations spanning from 2013 to 2014 not only as a place where insertions occurred, but also as themselves, true “insertions of multitudes” in Brazilian metropolises, that, in their refusal to bend to the function of industry of the general city circuit and its concomitant anesthesia, chose instead to affirm, potently, the circuit’s potential function of art. It is in the recognition of this desire to make art in all contexts and in the agency of this artful multitude – agencies of crabs and butterflies, wasps and orchids, of artists, militants, hackers and much more – wherein exists and resists the possibility for artistic institutions to reconfigure the meaning of the public in art.

Bibliographic References

Richard Florida. The Rise of the Creative Class. And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

Catherine Grenier. La fin des musées. Paris: Éditions du Regard, 2013.

Cildo Meireles. “Inserções em circuitos ideológicos” in Cildo Meireles. Rio de Janeiro: Funarte, 1981. In portugese. (Accessed September, 2014)

A. C. F. Reis (ed.) Cidades Criativas, Soluções !nventivas: o Papel da Copa, das Olimpíadas e dos Museus Internacionais. São Paulo: Garimpo de Soluções, 2010.

Martha, Rosler. “The artistic mode of revolution: from gentrification to occupation.”

Vladimir Sybilla. “Museu-monstro: insumos para uma museologia da monstruosidade.” Doctoral Thesis, 2014, IBICT/UFRJ.

Barbara Szaniecki. “Amar é a Maré Amarildo: Multidão e Arte”, RJ 2013.

Barbara Szaniecki. Sobre Museus e Monstros.

http://rogeliocasado.blogspot.com.br/2013/07/sobre-museus-e-monstros-por-barbara.html (Accessed in December 2014)

Barbara Szaniecki. “To Be or Not To Be a White Limousine.” (Acessed in December 2014)

Charles Landry. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators. London: Earthscan, 2000.

_

1 Publicness in Art was a series of regional seminars (2013-2014) coordinated by Instituto MESA and funded by the 10th edition of the Brazilian National Art Foundation’s (Funarte) grant initiative Networks of Encounters in the Visual Arts. The series aimed to reflect on the ethical and aesthetic complexity and public roles and possibilities of contemporary artistic production in a specifically Brazilian context in three separate regions – Rio de Janeiro/Niterói; Porto Alegre;/Rio Grande do Sul; Cariri/Sertão. The first meeting was held in Casa Daros, a new contemporary art center focused on Latin American art that opened in Rio de Janeiro in 2013. For more information about Casa Daros.

2 Inserções em circuitos ideológicos (Insertions in Ideological Circuits), 1970, is series of public art interventions by Cildo Meireles where the artist printed critical statements on Coca-Cola bottles and banknotes. For an overview see: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/meireles-insertions-into-ideological-circuits-coca-cola-project-t12328 The artwork and the artist’s related writings are recalled at various moments in this article and Meireles’ text on the project published in Cildo Meireles, Rio de Janeiro: Funarte, 1981 is cited throughout.

3 http://oglobo.globo.com/cultura/cildo-meireles-reve-seus-50-anos-de-arte-politica-poetica-11680129 e http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ilustrissima/2013/11/1365447-as-cedulas-de-cildo-meireles-e-outras-8-indicacoes-culturais.shtml

4 Vladimir Herzog (1937-1975) was a journalist born in the former Yugoslavia and a naturalized Brazilian citizen. Militant of the Brazilian Communist Party, he was tortured to death at Doi-Codi prisons. The authorities circulated the version that he committed suicide in jail. He became a potent symbol of freedom in the fight against the censorship and torture of the military dictatorship.

5 Amarildo Dias de Souza (1965-2014) was a bricklayer’s assistant and odd jobs man and resident of the Rocinha favela who was detained, tortured and killed (although nobody has been found) by UPP (Pacifying Police Unit). During the street protests he became a symbol of the fight against police violence. (Portuguese only. Accessed January 2015)

6 Gilles Deleuze and Clare Parnet. Dialogues. (Originally published 1977 Flammarion, Paris, France). New York: Columbia University Press, 2007, p. 2-3.

7 http://fadaiat.net/english.html

8 I refer to the concept of “General intelligence” of Marx.

9 Richard Florida. The Rise of the Creative Class. And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

10 The name “Pretos Novos” (New Blacks) was given to recent arrivals from Africa disembarking in Rio de Janeiro in the 19th century in an area of the city known as Little Africa. It was in this area, now the port region of the city, that the negro slave market was located – hence the name. It is now the locus of the research institute and memorial. Free translation. (Accessed January 2015)

11 Catherine Grenier. La fin des musées. Paris: Éditions du Regard, 2013.

12 Vladimir Sybilla. “Museu-monstro: insumos para uma museologia da monstruosidade.” Doctoral thesis, defended May 2014 Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (IBICT/UFRJ).

13 In June 2013, mass street demonstrations took over the main capitals of the country. The wave of demonstrations began with a demand by reducing bus fare but very quickly the demands of the people protesting multiplied.

14 In a recent visit to Rio de Janeiro, Jesus Carillo, director of the Cultural Program of the Reina Sofia Museum (Madrid, Spain), spoke of his experience with the network Conceptualism Del Sur (Conceptualism from the South) and Universidade Nomidade (Nomadic University).

15 UPP (Pacifying Police Unit) is a project of the Rio de Janeiro municipal government aimed at advancing security in the city’s favelas by way of a community police force to disrupt the powers that control these territories. Following the disappearance, torture and death of Amarildo Dias de Souza in 2013, the UPP has been sharply questioned.

16 Insertions op cit.

17 Ibid.

18 https://www.facebook.com/cedulativa/photos_stream

19 http://odia.ig.com.br/noticia/rio-de-janeiro/2014-09-19/policia-procura-autor-de-cartaz-que-gerou-polemica-entre-passageiros-da-supervia.html

20 https://www.facebook.com/SuperviaVergonhaParaOPovoCarioca

21 The poster text said: “The Supervia is exempt from paying the millions of dollars in fines to the public coffers because Agetrans is a regulatory agency facade, composed of people linked to the government and the business of the transportation sector.”