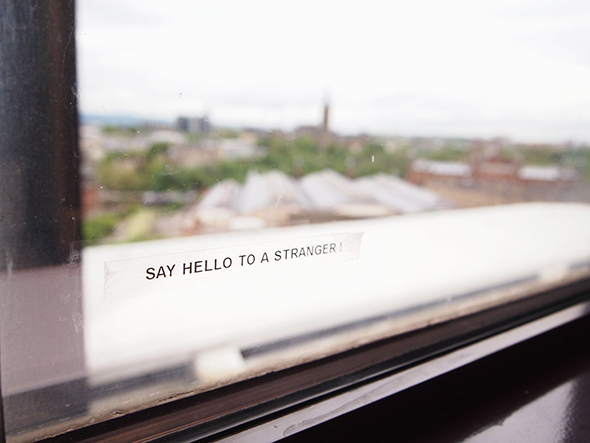

Say Hello to a Stranger: incidental conversations taken from patients installed on windows, courtesy and © Hans Clausen

Public Institution as Material – a project in process

Katie Bruce with Hans Clausen and Sarah Barr

YoHoArt is a pilot project created through the partnership of the Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA), Glasgow and Royal Hospital for Sick Children, (Yorkhill) Glasgow. This partnership between the two institutions intends to research and develop how a gallery public program (commissioning projects, sharing collections and learning programs) can operate within a children’s hospital context. The institutions are also interested in how this partnership can be used to support Article 31 (the right to play, arts, culture, leisure and rest) of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.1 This pilot partnership project uses an artist-in-residence model to generate new work with the young people that, in turn, facilitate their accessing the Young People’s Service2 operating within the wider hospital community. The implications of the youth-centered “play” approach of the UN Article on institutional practices as well as broader themes related to the potential of partnerships between art and health care organizations are part of GoMA’s long-term commitment to understand and reflect on the programs we offer and how different contexts influence the nature of that work.

YoHoArt was developed by Katie Bruce, Producer Curator at GoMA and Sarah Barr, Young People’s Services Coordinator at Yorkhill. The partners were looking for an artist who would be sensitive to working in a hospital or a therapeutic environment, and to the needs of young people. Sarah and Katie were open to different kinds of art practice and interviewed a ceramicist, theatre practitioners and a puppet-maker, following a call out for the position, and worked with two young outpatients on the recruitment process. The two outpatients were keen to help recruit an artist they felt would be fun, relate to young people and introduce patients to different kinds of art practices in the hospital.

They selected the artist Hans K Clausen, a recent graduate in sculpture with background in counseling. His sculptures use everyday objects or detritus and are playful as well as thought provoking.3 Hans describes himself as an artist with “an interest in visual vocabularies and the narrative qualities and emotive associations of ubiquitous objects”. The interaction between people and material culture is a recurring area of enquiry in his practice, and it is the relationship and dialogue that people have with their environment and the objects in that environment that captures his fascination. The work he makes frequently utilizes and re-appropriates the mundane materials of everyday life and is an invitation for the viewer to re-evaluate their relationship with those objects and possibly their place and role within that material environment. The opportunity to work in an institutional setting such as a hospital with its distinct visual vocabulary, aesthetic climate and powerful object associations was an immediate attraction to him.

His earlier career experience of working in Health and Social Care settings may have facilitated a sense of familiarity helping him to establish relationships and understand the procedural and cultural workings of the institution. Building and facilitating relationships was a vital part of the process of the residency as well as an intrinsic element of some of the works. Hans was inspired and influenced as much by the conversations around him as he was by the rich pickings in the hospital store cupboards and this gave some of the work a relational focus. The name adopted for the residency YoHoArt (Yorkhill Hospital Art) was itself a development from early introductory conversations and word games played out with young patients.

Hans has been working in the hospital for one or sometimes two days a week since February 2014, with month-long absences when Hans was on residency elsewhere. Hans was asked by the partners to spend the first half of the residency researching and understanding the hospital community and how patients are part of this. He is currently working on the next stage realizing ideas based on the conversations with that community, especially the young people, leading into a final intervention and seminar in the hospital during October.

A number of projects with artists have taken place in Yorkhill over the last four years, but have been primarily about enhancing the environment of the new hospital due to open in 2015.4 This partnership wanted to avoid clichéd approaches and to challenge the oft-held assumption that artists will simply decorate the environment by engaging an artist to work with the young people in the here and now. YoHoArt wanted to combat a stereotype of youth artwork on walls as a vehicle to enhance the hospital environment to more radically engaging the youth in thinking about and responding to their fundamental right to access art and culture through opportunities freely available to them as medical care and education are.5

These kinds of projects have both historic and current precedents. For example, the Artist Placement Group that was active in the 1960s and 70s where artists were “placed” in diverse institutions to creatively observe and input amidst institutional and organizational practices.6 More recently, the last few decades has seen increasing work bridging art and health. For example, engage, the UK arts education based network, edited a journal about “the contribution that the arts can make to hospitals and medical settings and how engagement with the visual arts can impact on the lives of patients, staff and careers”7.

“Public Institution as Material” is an essay compiled from edited conversations between Katie Bruce (KB) and Hans Clausen (HC) and meetings and reflections with Sarah Barr exploring ethical questions around the validity of an artist or a gallery organization working in a hospital, differing public institutional models, and questions of the identity of the artist and more specifically asking the question: is it the “atelier in the hospital or the hospital as atelier?”

Seminar with staff and patients to discuss the residency, courtesy and © Katie Bruce

KB

When Sarah and I initially discussed the residency, we were interested in the awareness of article 31 both for young people and for the hospital staff. If we take the position that young people don’t lose their rights when they go into hospital and thinking about rights beyond the right to medical care, the Play Service is fundamental to meeting article 31 in a hospital setting. But how does the hospital institution look at art, culture and access to that? That is one of the questions I am interested in – why a gallery institution is working in partnership with a hospital, and how can this be most effective? Actually questioning why would a gallery/museum like GoMA work there, are we the appropriate institution?

HC

Being there one or two days a week and, even when I am there kind of multi-tasking a bit, it’s difficult to really unpack that question too much. Identity, that is one of the main things. Like when I buzz to get into the wards. I have to think, Yeah they are going to ask, “Who is it?” and often I will now say, “I am Hans from the Play Service”. When I was first there I would have said, “I am the artist-in-residence”. But it feels like it is easier if you have an easily defined identity that other people can link you with. But I guess something like that has parallels with the young people. They come in as “Tom” but they become the patient on 3rd bed.

KB

Do you think you have lost your practice as an artist in there? You are saying you have lost your identity?

Chair with surgical gloves, courtesy and © Hans Clausen

HC

No, I think it’s just been a little bit under the radar. Part of that also relates to the very prescriptive expectation that most people have of what an artist will do in the hospital. I find myself having to be quite shrewd, not shattering illusions and not creating obstacles for myself but, in some ways, to go so far down the road of being the person that people expect the artist to be but not losing my own vision for the role either. There is something about what I might bring, even conceptually what I think I am doing, that comes up against the reality of what the child wants to do or what the ward manager would like to be done… I don’t think it’s about the loss of the artist identity. There is something about an institution that imposes a compromise. I think as an artist in residence there is also an element of the educative, an artistic and educative process. What is art? Why is it art? More than just a painting on a wall or a mural… thinking about challenging how people look at things, how we look at ourselves through art. But that is a relational thing. That takes time. I don’t know if it’s an unrealistic thing or if maybe it just needs a different approach, or whether it just needs perseverance and just being more clever…

KB

…or rethinking how the museum works in that space? We left it very open in terms of your time with that and also with our budget. It maybe questions about how things are thought through.

HC

There’s a comparison that I drew the other day between working in the hospital as an artist and working, as I used to, as a counselor. The connection here is that the view of counseling would often be that as long as the counselor turns up and somebody wants to meet the counselor then counseling can happen. It can happen anywhere. The reality is that what we need what we call, the “therapeutic space”, the environment has to be right. So I find myself thinking, in the same way I used to argue, if you want to have a counselor or an artist in a hospital the space provided for them is really important… Is it an art space or is it an art studio? Is it a classroom? Is it a games room? Is it a multi purpose suite? Where does the artist belong when they go into the hospital?

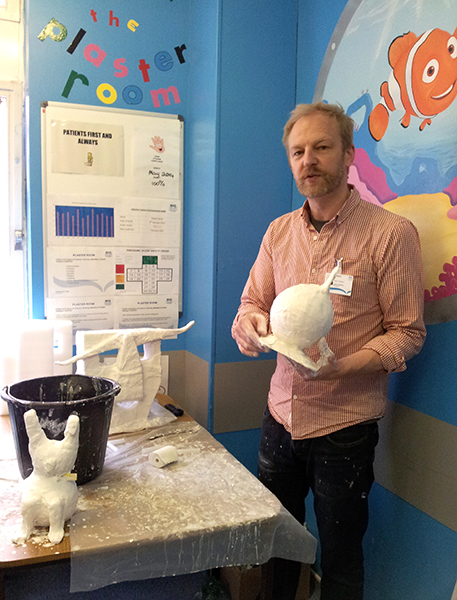

The Plaster Room where children get their plaster casts fitted for broken bones, courtesy and © Hans Clausen

KB

For me that relates to, does the gallery belong in the medical institution?

HC

How much can you expect the gallery ethos and the gallery conditions for encounter or participation to be replicated in a hospital? I don’t think it is too much to ask but I think, as it stands, it is a huge challenge. For instance, it has been problematic getting access to the young people or the young people getting access to me and the work at times… I was just thinking there of two different 20-minute examples of engagement with young people… The first one… I had been given a list of young people on the wards so that I can find them. Within 20 minutes I have maybe gone to four of these wards and have been unsuccessful so far because I have spent several minutes waiting to speak to the nurses in charge; they’ve gone off and spoken to somebody and the young person wasn’t back from theatre or the young person wasn’t feeling well… I had known what I was going to do and 20 minutes later I have seen nobody. A different 20 minutes is me leaving Zone 12 with the gorilla [part of one of the art projects Hans was doing] to go to install it in the parking booth. This should be a two-minute walk, but it took 20 minutes because suddenly there was all this interaction. Literally it was five steps forward and stop, another photo, another child holding the gorilla’s hand. But that’s where it has been the most exciting and spontaneous engagement.

Gorilla/Guerilla in the parking booth, courtesy and © Hans Clausen

Gorilla/Guerilla at the front desk, courtesy and © Hans Clausen

So even if the artist has a floating presence (I am still convinced there needs to be some kind of base) I think the invitation to play is not about “yes you have had your 20 minutes of play today so we have done our job”. It’s just that there are constant invitations to play, opportunities to play and people can choose on a whim if they want to engage or not. That freedom seems quite important.

Magic Mask from hospital equipment, courtesy and © Hans Clausen

KB

There are commonalities in what I am asking artists to do in complex public spaces like Atelier Public #2. The conversations were very similar, even though they were in entirely different contexts. One was actually positioned as an exhibition within a public institution trying to a play, an adventure playground or a studio model within that institutional gallery model. Whereas within the hospital we are testing a gallery or an artist model, still potentially like another studio model within a kind of medical environment.

HC

Could we have transposed Atelier Public to a public space in the hospital and just replicated it? If there was, say, a chunk of the canteen, a room off the main corridor, or we could have had a whole bunch of hospital materials and sticky tape and glue and people just invited to come in and create this, and create an exhibition in this space, use these materials in your own time. That’s not far from what I was thinking I was doing inviting young people to do something, to find something in the detritus of the hospital to make something. But it would have been a lot easier and maybe would have been more accessible if I had been able to say, here is the “space” and here are the art materials.

That would be a very public thing. It would be seen by everybody and it would be engaged with by some of those people… [the hospital] is a public institution but to actually be very visible is quite hard. An example I think is the notice boards. How many posters do you actually have to put up to get noticed? I think the Queen’s Baton coming round there was literally, you know, every two or three feet there was a poster8. So hundreds of posters just to make sure that event was seen. But in amongst that, hundreds of other visual images are around. Being seen, raising your identity and your role above all that, is pretty hard.

Visit by patients and parent to GoMA facilitated by Hans, Katie and Sarah, courtesy and © Hans Clausen

KB

Whereas people will come to a gallery with the intention of seeing art. They might not like the art that they see but…

HC

…they know what they are coming to…

KB

They know crossing the threshold that it’s a conscious step they’re making. I suppose what we have talked a little bit about is the conflict of models and how you might be able to operate within that at the hospital. I suppose as we are writing this up Sarah might have a reflection on this through her knowledge of how the hospital functions.

Reflections

Is it the ‘atelier in the hospital or the hospital as atelier?’

SB

Hans, I will start with point in the conversation where you spoke about the need for a sole art space and how that affects the artistic process for both kids and artist. This has been raised by several artists before and will continue to be unresolved as within all parts of the hospital, mess (and artistic mess!) always has to get tidied away to leave surfaces clear for cleaning as much as possible. Many materials would – such as paper or anything unwipeable – be thrown away at the end of each day. Basically, the art space on each ward could never happen in an acute care hospital due to infection control policies.9

Vacuum Packed Aberdeen Scarf, playing on the idea of sealing infections, courtesy and © Hans Clausen

This leaves the artist with less of an obvious identity and requires them to be part of the greater whole. This will be even more the case in the new hospital, as very few people will have a base or office. Instead we will all be constantly in the patient realm and hot-desking.10 There is no provision for quiet thinking time or a sense of having a base to help inform our roles.

If art and art conversation are going to happen in an acute care hospital it needs artists who can walk the tightrope between subsuming into the whole and remaining independent, thinking enough to be inventive and help create new things with kids.

HC

I have tried to “walk the tightrope” and through the application of visual vocabularies challenge conventional perceptions and expectations of the institution and its perceived limits/boundaries/rules. For me the “atelier” is important. Imagine a space which is not aesthetically over designed and has been left with bare walls for the young people to come in and have the freedom to change the aesthetic, which can then be razed the next time someone else is in the room. For me that doesn’t exist in the hospital, everything is managed. I realized that this “atelier” would not be possible in the current institution, therefore, some of the work has been to inject humor into the institution, which may have inter-relational therapeutic benefits, and using relational art approaches to intercept any existing senses of routine, complacency, boredom, disillusionment.

I am interested in using materials in the institution to encourage a “second look”, a reflection of what might be perceived as mundane. Bringing renewed value to ubiquitous processes, materials or spaces and introducing alternative methodologies of looking, perceiving, communicating, relating, maybe even working practices?

Prescription View, transforming the prescription trays for medicine into a view or picture – the idea of prescribing art as much as pills, courtesy and © Hans Clausen

Cup Holder Transformers, courtesy and © Hans Clausen

A project in process

KB

This project was conceived in terms of its relationship to play and Article 31 from its conception. To define play is a thesis in itself, but for me it is the fact that it is constantly kept in process, depends on who is there at the time and the invitation to be part of that, and that sometimes its purposelessness can ignite a different question for an observer. The fact that Hans has used very little of the project materials budget sourcing materials in the hospital itself or even people or the spaces there is exciting. It is like the institution itself is unfinished and only completed by the actions of the hospital community at that time, and by this I would include an artist. Currently there is the difficulty for the artist coming in excited by what is around them and the opportunity presented by the institution as material, but also managing expectations of what that institution expects based on previous experiences.11

HC

My experience of the institution as material is that it is more about relationships than anything else. I think I may have said this quite early on that it’s more about conversation and these conversations are creative. These conversations are, I think, as valuable in terms of output as an activity. We are at the stage of building on these conversations in the project, however, findings ways to be seen within either a visually busy environment (e.g. the “aesthetic soup” of the hospital notice boards and public areas) or a particularly restrictive clinical environment (e.g. highly controlled infection/barrier clinical areas) is very difficult. So it can be challenge maintaining artistic identity, integrity and vision while working within limiting conditions and the constraints of staff expectations.

Drip stand – decorated, courtesy and © Hans Clausen

KB

But some of these conversations have resulted already in visible “outputs”, maybe not predictable, like the use of the parking booth for the gorilla (images 4-6) through conversations with a facilities manager, or fixing of corridor lights for a possible artwork on the notice board without going through the job requisition process.12 I think it is interesting that the artist can come in and focus resources or thinking to change things, even subtly, in an institution. Art (or play) as an “irritant” to the institution to encourage people, to allow people, to question a bureaucracy or an idea differently to the structure in place is important. Otherwise you are in danger of smoothing over questions of practice in the institution by relegating the role of the artist or art in to an aesthetic “plaster” for the institution.

SB

In an overstretched NHS (UK National Health Service) play services and arts are often seen as soft extras by some financial managers. In this climate of cuts we need to prove ourselves over and over again, with as much hard evidence as possible, to show that arts and play are an important component in patients’ recoveries. So while I think people are interested in Article 31, at the end of the day the institution will be financially constrained to see acute care as medical not psychosocial.

Reflections to consider in the final stages of the project

HC

It may be that there is the role of the artist, to bring people together, to provide a “leveler”, a common ground, to encourage people to connect, create opportunities/conversations that cross disciplinary boundaries and diffuse professional identities. We did it very lightly with the small seminar we had, but through a greater visibility we could challenge conventional perceptions of art and expectations of art within specific contexts. e.g. “art in hospital”, “modern art”, “professional art”.

SB

I think that it is helpful to try to answer Katie’s first question about why work with the gallery in the hospital at all? I would say it is to enhance both staff and patients psychosocial wellbeing through visual art. This leaves it very broad, but if galleries are to have a role as mediators between people (art and the public or public and the public) to help create better communication and understanding, then surely bringing a questioning and open-ended creative mind into the hospital mix will do that.

KB

Can the gallery practice and work with artists be used to critically challenge working practice within the hospital, or is it to perform the sole function of an environment enhancement tool or a therapeutic/entertainment opportunity? How can an artist operate within this new environment, but also question, or subvert, the models of working and design spaces for themselves and the young people that are creative and valued? This is something we can take to the concluding intervention and seminar for the project. We want this to inform future aspects of the partnership, especially as the working environment will change with the opening of the new children’s hospital in 2015. Where, in certain ways, the reflective spaces which our gallery operates with, including a studio space, will be even more absent.

_

1 GoMA has worked with the International Play Association (IPA), since 2010, to question how an art institution can meet the rights of the child in terms of Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. This way of working strives to put the child at the center of the discussions on access to art and culture and for them to be the agent that drives the nature of the cultural offer. Article 31 of UNCRC is commonly known as the “play article”, however, it also places on governments, signed up to the Convention, a duty to deliver programs for young people in terms of access to arts, culture, leisure, and rest. Katie Bruce was involved in the writing of the General Comment on Article 31, approved by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child on 1 February 2013. Since then GoMA has continued to work with IPA Scotland to raise the profile of Article 31 in the Arts sector in Scotland and reference to it is now in the Creative Strategy for young people launched by Creative Scotland (the public body that supports the arts, screen and creative industries in Scotland) in November 2013. YoHoArt was a pilot project to see how the partnership of hospital and art institution can respond to Article 31 and change how it might think of the services that it provides for young people in the hospital.

2 The Royal Hospital for Sick Children (Yorkhill) provides acute care for children from all across Scotland. This includes thousands of young people aged 12 years and older every year. The Young Peoples Service provides age-appropriate activities for these patients: workshops, youth clubs and other fun bedside and group work activities. Many young people are in and out of acute care very quickly so the model of providing activities has to be flexible from a one-off session with a young person to perhaps several contact sessions.

3 http://www.hanskclausen.com/gallery/

5 There is a hospital Play Service available for patients. This consists of a number of play workers who visit the wards. They work around the doctors’ schedules and the hospital education department to provide activities for the children. Often they do not have a specialty or training in working with young people and services are designed more for younger children. In the setting up of this project we set to differentiate the work Hans was doing as not offering just activities to the young people to alleviate their boredom, but how the interaction with Hans and any resulting interventions would be visible in the hospital and influence their care.

6 Artist Placement Group was established in London in 1966 by Barbara Steveni and John Latham to arrange for artists to take up placements or residencies in companies. The theory was that the artists were not there to use the services of the industry, but to use their creativity and practice to have a positive effect on the business they were placed in. Often sitting outside of the bureaucracy of the organization, the artists would be able to show staff other ways of functioning within the institution.

7 Engage 30: Arts and Healthcare, Summer 2012, Published by engage, London. Engage is the national organization for education in galleries in the UK.

8 The Queen’ Baton is the Commonwealth Games equivalent of the Olympic Torch. It travels round participating countries before returning to the home nation to be presented to the Queen at the Games opening ceremony.

9 The ideal resolution of having a space where the artist didn’t feel like they were undermining leisure or recreation spaces was discussed with hospital management before Hans started. There was some talk of a space being identified so this was at the back of the partners’ minds but has so far not materialized. It creates a problem for leaving work from week to week and leaving any kind of research or studio process open for others to see unresolved works.

10 Hot desks are where more than one employee uses the same desk at different times when the others are not there. Often there is a booking system in place to secure a work station. This is how the office or working spaces are going to be structured when the new hospital opens in 2015.

11 Hans has been asked to paint murals of Disney characters on wards by staff, as that is often what their experience is of what artists will do. The project has been trying to open up the possibilities for art making for children and young people in the wards and hospital.

12 The gorilla intervention in the hospital parking booth (images 4, 5 & 6) took a lot of negotiation with the parking attendant (Tam) and he was very skeptical. Hans managed to get the booth cleaned and once installed Tam began to take ownership of the work, looking after it and adding in elements like a jacket and bananas. This pride in the work may be partly because his working space had never been cleaned and now it had been “noticed”, but also because it changed his relationship with visitors to the hospital. “People are probably quite grumpy to him over where to park, etc, … so it’s given a whole new lease on life to him and his conversations with patients and families. So that wasn’t what the intention of the piece was at all but that’s great if that has been a real success. It’s not just become a talking point it has actually changed relationships between certain members of staff. But that, yeah, wouldn’t have gone into the proposal, if we are going to put a gorilla suit (stuffed) in your parking booth and that will have some effect on a sub group of staff.’ HC conversation 6 August 2014.