Public Reading of the Figueiredo Report

Fábio Tremonte

The presenter indicated that to her the Colón statue was not offensive. To which Ortiz replied: “Of course, because you are white”.1

El Pais, August 5th, 2020

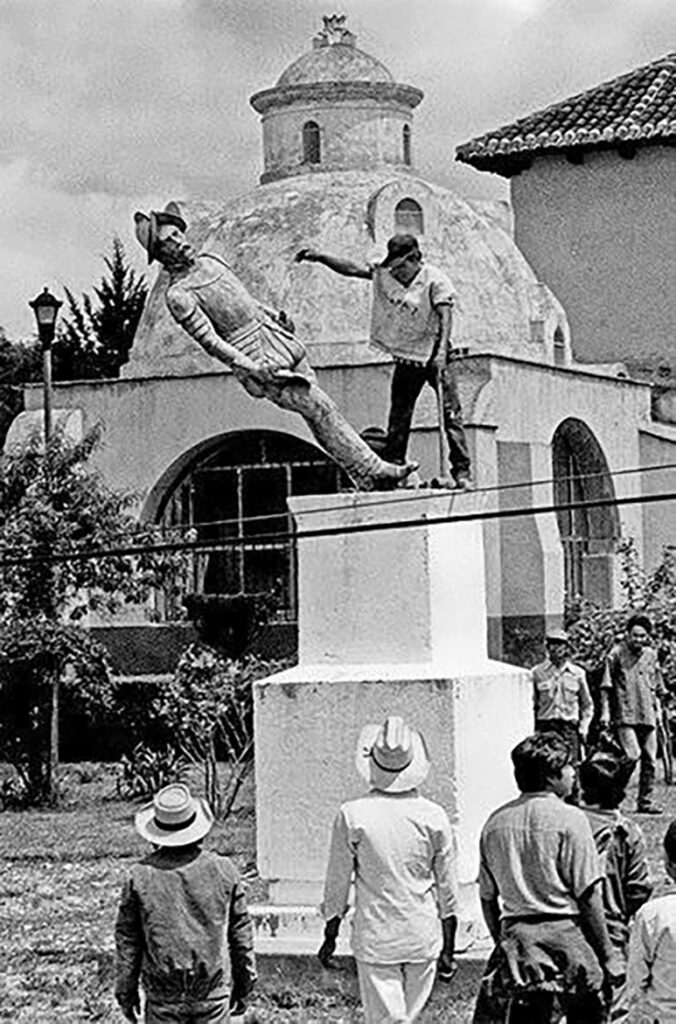

June 7, 2020, in Bristol, the statue of Edward Colston was toppled and thrown into the city’s main river.

June 9, 2020, in Boston, a statue of Christopher Columbus was beheaded during the night.

June 11, 2020, in Lisbon, a statue of Father Antônio Vieira was destroyed.

June 22, 2020, in Washington DC, a group of protesters tried to bring down the statue of Andrew Jackson.

July 4, 2020, in Baltimore, a statue of Christopher Columbus was demolished.

June 9, 2020, in London, a statue of Robert Milligan was removed from its pedestal.

Attempts to retell official history from other places.

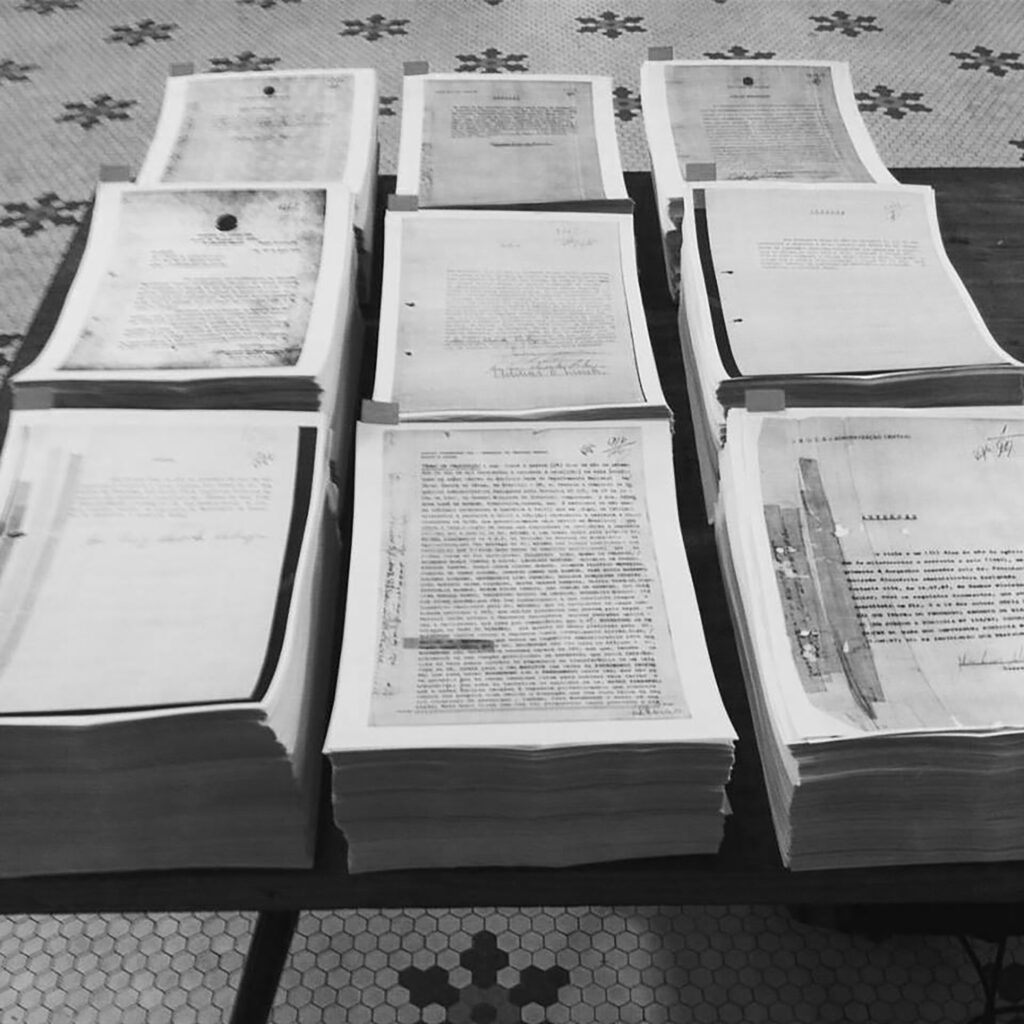

The Figueiredo Report was compiled as a result of an investigation of a parliamentary inquiry commission conducted in 1967 by the attorney Jader Figueiredo Correia. In its 31 volumes (volume 2 has been lost) and almost 7000 pages, the Report chronicles crimes against the Brazilian State committed by employees of the extinct governmental division known as the Indian Protection Service (SPI) and the irresponsible and criminal use of the entire civil structure including the illegal lease of land and loan of materials and equipment such as typewriters or tractors, and, principally, the accusation of violent actions undertaken by these same civil servants against indigenous populations during the 1940s, 50s and 60s.

After a fire at the Ministry of Agriculture in 1967, the Figueiredo Report was believed to have been destroyed and went missing for more than four decades. In 2013, during research by the National Truth Commission, it was found in cardboard boxes at the Museu do Índio [Museu of the Indian] in Rio de Janeiro.

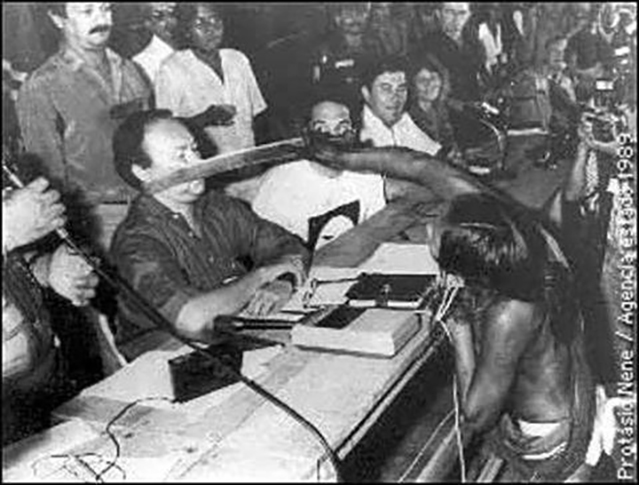

The world met sister Tuira Kayapo in 1989, at the meeting in Altamira against the construction of dams on the Xingu River. She appeared in the room with her war paint and a machete. She approached the president of the Brazilian electric company, held a machete to his neck, and proclaimed that the indigenous people and the entire Amazon considered interventions in the river to be an act of terrorism and war. She said:

“You are a liar! We don’t need electricity! Electricity is not going to provide us with food. We need our rivers to flow freely, our future and that of all humanity depends on it. We need our forests intact to be able to collect our food. We don’t need your dam!”

She bid her farewell saying:

“My nickname: offended;

My name: humiliated;

My status: rebel;

My age: the stone age.”3

***

In the document, there are detailed reports of theft, torture, rape, illegal imprisonment, poisoning, intentional contamination, bombing of villages, murder of leaders, enslavement, and massacres. Crimes committed against Indians by private and public entities, in clandestine collusions or as the outcome of official decisions. Fábio Tremonte proposes, in this work, that the 29 volumes of the report should be read, in their order, by anyone who visits the exhibition and for the time it lasts, a collective and voluntary effort to activate the memory of so many atrocities committed in the past against indigenous peoples and still perpetrated to this day.4

***

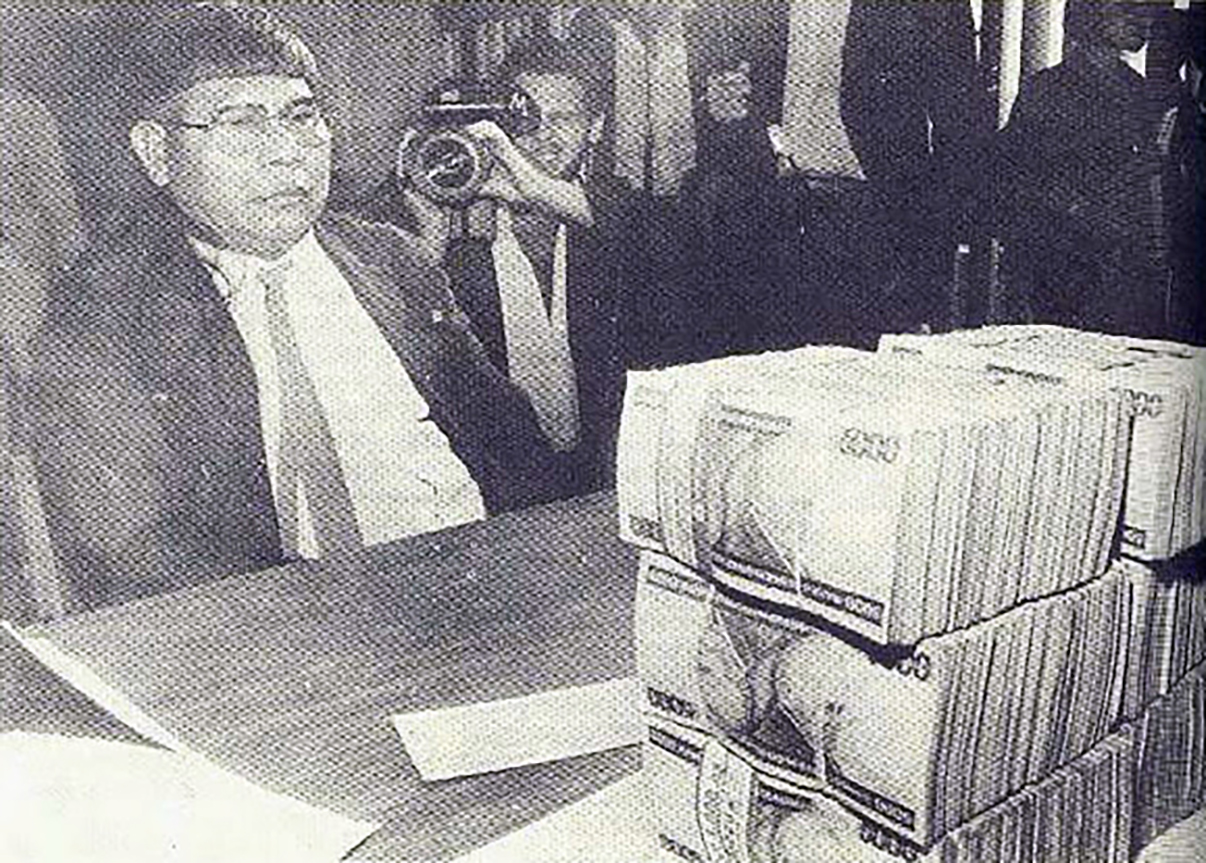

He was the only indigenous federal deputy in the history of Brazil. Elected by the PDT / Rio de Janeiro (1983-1987), he was responsible for the creation of the Comissão Permanente do Índio [Permanent Indian Commission], ensuring the indigenous problem received official recognition. He was a fearless activist for indigenous rights, confronting army generals and top leaders, at the time of the military dictatorship. He was also the only deputy in Brazilian history to denounce corruption schemes amongst politicians. In an openly public gesture he returned the 30 million cruzeiros he had received in an attempted bribe by businessman Calim Eid in 1984 to vote for Paulo Maluf, the military candidate for the Presidency of the Republic at the electoral college, in an election that was to supposedly mark the end of the military dictatorship. He voted for Tancredo Neves in support of indigenous rights, still as yet to be implemented.

He failed to be re-elected in the 1986 elections, but he remained active in politics for several years. He died of diabetes and hypertension on July 17, 2002.5

***

A proposition of Escola da Floresta [Forest School] – an alternative school initiative in São Paulo led by the artist Fábio Tremonte – the Public Reading of the Figueiredo Report occurred for the first time at the Oficina Cultural Oswald de Andrade in São Paulo between 2016 and 2017. The proposition was then reassembled in two subsequent iterations: in 2018 at the Paço das Artes in the exhibition Estado(s) de Emergência [States of Emergency] curated by Priscila Arantes and Diego Matos and in 2019 for the exhibition A queda do céu [The Fall of the Sky] at Caixa Cultural in Brasília curated by Moacir dos Anjos.

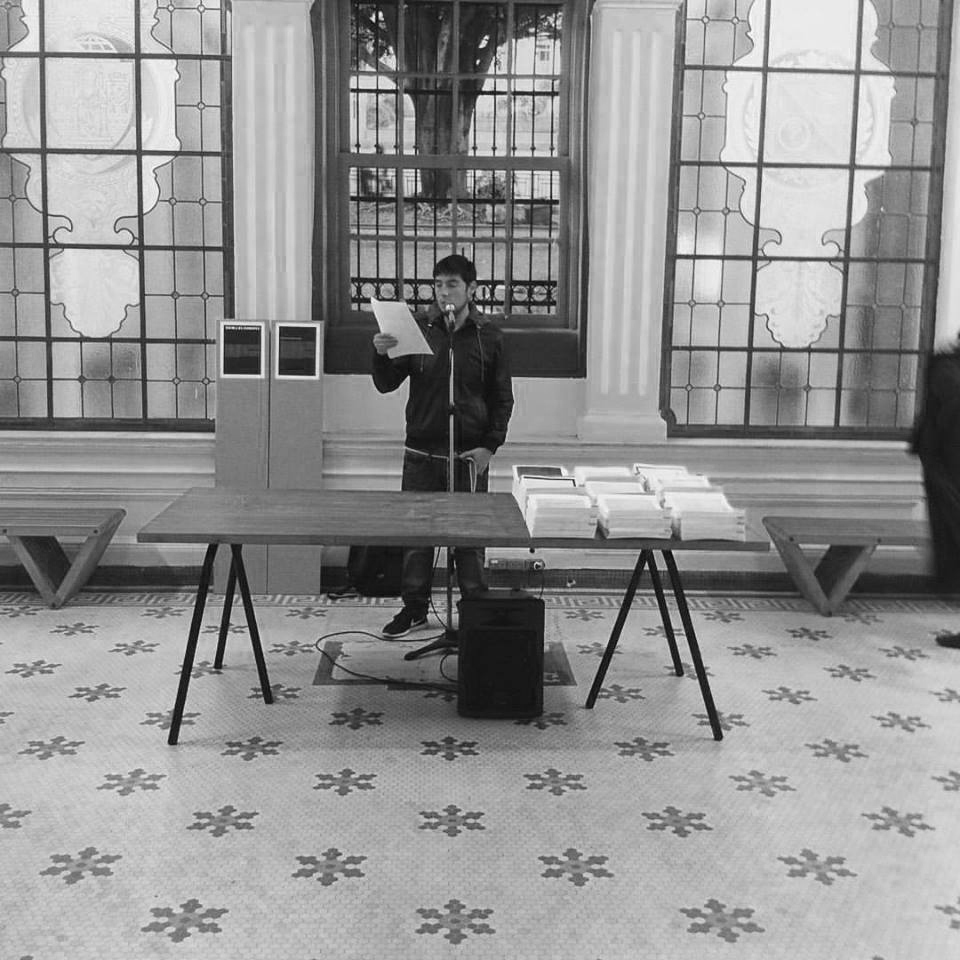

The “public reading” and installation features a table with the 7000 pages of the report organized in thirty paper piles together with an open microphone connected to a loudspeaker. It is vitally important to engage the educational sectors of the exhibiting institutions, as the initial approach proposes beginning with a conversation about the conditions of indigenous populations in Brazil since 1500.

After the conversation, the visitor is invited to take a page of the report and read the typed text aloud into the microphone. The speaker amplifies their voices. Here, the printed words of the report, for so long hidden from view, are made public and heard by other visitors, and those passing by on the street, echoing the history and official reports of the violent and genocidal treatment of the Brazilian State against the indigenous populations and their territories.

From a curatorial perspective, making public, in an accessible and eloquent way puts us in direct contact with what the report portrays in such a raw manner, thus allowing the public to be affected, in one way or another. Staging a reading of the report and, actually realizing it, alerts us to the broad and complex issues of invisibility in the country’s history: the stories of thousands of indigenous people who were violated, in one way or another, by the “civilizing barbarism” of the Brazilian State and its economic elite..6

***

Escola da Floresta is a project that seeks to be a space of intersection between artistic and pedagogical practices. It is a nomadic, temporary, transient school, without furniture, without a fixed program, without hierarchy between those who teach and learn with the aim of fostering multiple and diverse knowledges in a search of experimental and radical pedagogies. Escola da Floresta borrows strategies and procedures from the fields of art and education in order to create folds, creases, tears, and stretch the fabric created in these segments and, thus, transform and imagine other worldly possibilities. For the Public Reading of the Figueiredo Report, two elements familiar to the school universe are important: the historical narrative and reading aloud. These two procedures are put into play in the public space of a cultural institution with the desire to provide another corporeal-intellectual-affective relationship within official history, twisting it to show that history is not a one-way street. Here we propose to “brush history against the grain” as Walter Benjamin says.7 Firstly by reading aloud. When a participant engages and decides to read the text of the report into the microphone, they not only participate in an artistic proposal, staging or performance, but also, they primarily give voice to air a text of denunciation regarding the treatment of indigenous people by the Brazilian State. Reading aloud is another development in an evolving fabric of witnessing that began with the investigation of SPI officials in the 1960s, followed by the establishment of the parliamentary inquiry commission, the writing of the document’s text, the digitization of the report after it was found in 2013, and now its public presence on the internet. To read aloud is to bear witness to this barbaric history and to what the original peoples have suffered and to understand that it has been this way since the arrival of the European in this land called Brazil.

Another important aspect is to highlight other historical narratives about indigenous populations in Brazil. Narratives not officially told in schoolbooks or that follow state curriculum. Seeking a counter-narrative is also an integral part of the Public Reading of the Figueiredo Report. In this sense, educators play a fundamental role in setting the stage for the Reading by facilitating the relationship between visiting publics and its proposition. Imbued with sensitivity and another approach to the historical facts than that written by the winners, installation presents the visitor with other readings of these facts and, at that moment, invite them to read.

Just like that the open microphone is left by the artist at the Oficina Cultural Oswald de Andrade [inviting visitors] to read the more than seven thousand pages of the Figueiredo Report, a report that was supposedly eliminated in a fire at the Ministry of Agriculture, found after 45 years at the Museu do Índio, in Rio de Janeiro. People eat their speech. They swallow it dry.8

***

Fábio Tremonte

Artist, educator, researcher, and anarchotropicalist. Currently he is study for his doctorate at Universidade de São Paulo (ECA/USP). He chose art so as not to turn into a specialist, working in the kitchen in the morning, as an anthropologist in the afternoon, and a DJ at night. He brings people together in the kitchen, at school, and on the dance floor, but this is not all. He prefers to write in portunhol [suggesting hybrid tongue drawing on the term used to describe the spoken language that is a mix of Portuguese and Spanish). In 2016 he created Escola da Floresta, a nomadic school permeated by diverse forms of knowledge, ways of learning and teaching, and imaginings of other possible pedagogies. He acted as pedagogic curator for the 2017- 2018 Trienal de Artes Festas Entre pós-verdades e acontecimentos and in 2020 for the Valongo Festival da Imagem. In 2017-2018 was curator for the artist residency program Barda Del Desierto in Patagonia Argentina. His work has been included in various exhibitions such as Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo, Museu de arte do Rio de Janeiro, Centro Cultural São Paulo, and Paço das Artes among others.

1 Peio H. Riaño. “Daniela Ortiz: ‘Conforme tu voz crece, la violencia contra ti también’”. El País, 5th August, 2020 https://elpais.com/cultura/2020-08-05/daniela-ortiz-conforme-tu-voz-crece-la-violencia-contra-ti-tambien.html?outputType=amp&__twitter_impression=true [Accessed August 2020]

2 Fábio Tremonte, “sem fé, sem lei, sem rei” Periódico Permanente vol. 4. no.7 2016 http://www.forumpermanente.org/revista/numero-7/conteudo/politicas-do-esquecimento/sem-fe-sem-lei-sem-rei [Accessed August 2020]

3 Ibid.

4 Introductory text to [Leitura Pública do Relatório Figueiredo] for the exhibition A queda do céu in 2019 at Caixa Cultural in Brasilia curated by Moacir dos Anjos.

5 sem fé, sem lei, sem rei op.cit.

6 Curatorial text about [Leitura Pública do Relatório Figueiredo] for the exhibition Estado(s) de Emergência in 2018 at Paço das Artes, São Paulo, curated by Priscila Arantes and Diego Matos.

7 Benjamin notes that history sympathizes with victors and their heirs and that there is “no document of culture which is not at the same time a document of barbarism”. It is then the “historical materialist’s task “to brush history against the grain.” Walter Benjamn, “On the Concept of History” in Walter Benjamin. Selected Writings Vol. 4 (1938-1940) eds. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2006) pp.389 – 400, 392.

8 Kamilla Nunes, Embarcação, Masters thesis in visual arts UDESC [Universidade Estadual de Santa Catarina] | Kamilla Nunes | 2017. [T.N. The Portuguese “come-se a fala” is translated literally as “eat their speech” and should not be confused with the English “eat their words” which implies regretfulness or misplaced speech].