Talking Across the Cypriot Buffer Zone: Making the Invisible Visible

Case Study Editors: Esra Plumer-Bardak and Evanthia Tselika

Introductions to Cyprus, more often than not, fall into two categories: one focuses on the geographical features of its physicality as a small island and proximity to other countries and the other on the unresolved political conflict between two of its main inhabiting ethnic groups Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots. The later is described by the artist Alev Adil, in one of the videos presented here, A Small Forgotten War, as a “sour extended sulk”, stuck in a stale-mate for over half a century.

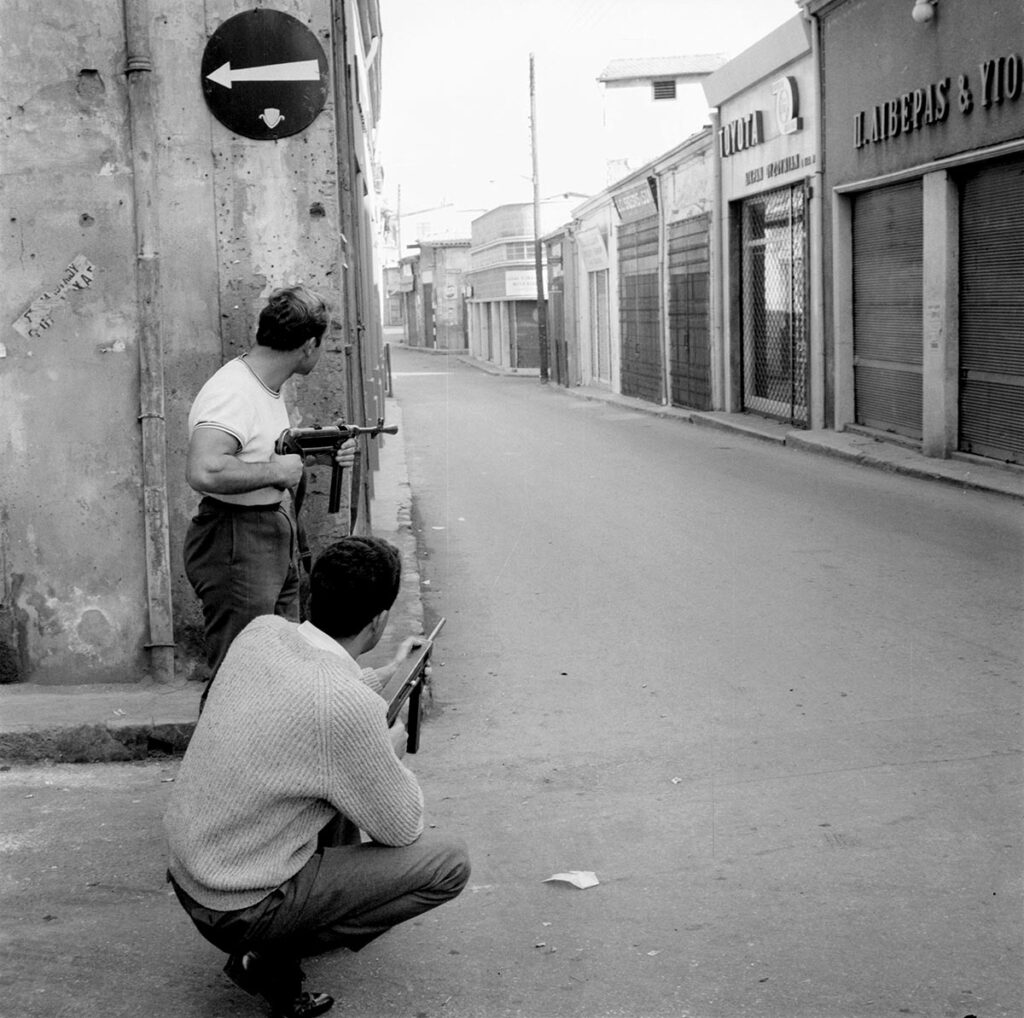

We are two art historians who live in on either side of the divided Cypriot capital city of Nicosia – divided between these ethnic groups and their respective national jurisdictions. This case study forms a dialogical ground for us to reconsider together the scar of this dividing “green line,” the materiality of the Buffer Zone, and its imagined realities and hidden lives through artistic practices that are socially situated and commonly activated.1 Core to the dialogue between us has been expanding this discussion to include artist, researcher, and ativist colleagues. What has emerged is a polyvocal case study of Cyprus featuring a mapping of socially situated and critical art practices by independent organizations and collectives that work across the Buffer Zone in Cyprus and works by artists that demonstrate how art practice relates to notions of activism. This conversation arises from our own involvement in developing art projects that insist on creating flows across the divide and on further shaping commonalities between us. As we write this editorial, it is the first time since 2003 (when the restrictions to movement were lifted) that the Buffer Zone has become hard to cross, and we cannot easily meet one another because of the movement restrictions imposed by each respective side for Covid-19. The no-man’s land, also called the Buffer Zone (approximately 180km long with a width that varies from a few meters to a few kilometres) extends from Pyrgos Tyllirias to the outskirts of Famagusta. It is home to and patrolled by the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) and surrounded by the Turkish and Greek Cypriot troops that parole the ceasefire line. The physical Green Line consists of barbed wire, roadblocks, checkpoints, fortified houses, and sandbags.

| “The Green Line” The 1963 line drawn with a green pen on the Cypriot map by General Peter Young, who was head of the British colonial forces, evolved into the contemporary Cypriot no-man’s land. Barbed wire and division blocks were set up during the inter-communal fighting of the early 1960s by the peace-keeping force, and in 1974 the Green Line (basically the demarcation line at which the fighting ceased) became fixed and firmly divides the island to this day. |

Modern history summarizes the story of this “line” as having been formed in 1964 and subsequently hardening to the point of becoming impenetrable in 1974. Since then, however, the endeavors of Cypriots on either side have gone beyond the mitigating efforts of political representatives and peace keeping forces.2 Beyond the line, there are individuals and civil society groups who on personal and communal levels have been working to create ways to work through, deal with, engage, and confront shared struggles and difficult subjects. In so doing they build common experiences whilst maintaining unique perspectives in order to avoid hiding (remaining) under the heavy blanket of trauma and strife that has been buried in the years of silence and distance.3

The Buffer Zone, can be seen as the culmination of two definitive characteristics, dividing the physicality of its land, its people, as well as symbolizing its political deadlock, pushing either side towards seemingly diametrical views and its neighbouring counterparts. Over the years, after the erection of the border, many people, whose movements were already restricted prior, were forced to move across the Buffer Zone, dislocating over 200,000 people between the years 1963-1975. Emigration took place not only across this border but also beyond it, with just as many Cypriots migrating abroad as early as the 1950s to escape threat (also imposed within their own communities), and again in the 1960s, to search for prospects the island could not offer (such as education, jobs, industry), more often than not permanently being displaced from their homes. The experiences of the Cypriot diaspora are often drowned out, though they are at times amplified from all over the world, as in the artistic performances and writing of Alev Adil, who moved to Anamur, Turkey, as a child, and later to the United Kingdom. In her audio visual poems Adil’s memories of crossing the line narrate the journey from a child’s perspective, her footsteps “invisibly scribbling along the scar of the green line…” This seemingly playful act of crossing and recrossing quickly disintegrates and merges with the more sinister aspects of this experience with visual descriptions of defunct places such as the swimming pool she swam in everyday of the summer, now sandbagged. In the one of the case study’s features, Architecture of Forgetting: Journeys into the Dead Zone, we see images taken by Adil in between 2006 and 2008, a time in which Cypriots were still numb. Although in some cases people at this time were activated and moved to become more compassionate by the potential of unification and talks after the twenty nine year strict segregation that divided us was shifted in 2003. Contemporaneous projects that explore new ways of looking at the Buffer Zone can be seen as examples of this.4

The life of the Buffer Zone, which as Anna Solder Grichting notes, has for almost the last fifty years been an ecological heaven for wildlife, has also shifted since the restrictions on North-South movement were lifted in 2003.5 In the last seventeen years a total of nine checkpoints have opened to allow controlled flows of movement through the Buffer Zone. This movement has also transformed the life of this in-between space, as more and more buildings have been restored and more points of contact have been created, with the iconic case of the Home for Cooperation at the Ledra Palace Checkpoint opening its doors in 2011.6 The roots of bi-communal cooperation can be traced back to the Nicosia Master Plan, set up in 1979 and led by the then mayors of the city, Lellos Demetriades and Mustafa Akinci.7 Since the late 1980s we see activists and artists trying to collaborate together and form bridges through culture across the division.8 A key example here is the case of Satiriko Theatre and Lefkosa Belediye Tiyatrosu [Nicosia Municipal Theatre], who have been working together since 1987.9 In the visual arts we see artistic production across the division from the early 1990s and this has been much discussed in the last few years. Artist and scholar Haris Pelapaissiotis introduces the concept of “Buffer Zone” art, also articulated by Özgül Ezgin and Argyro Toumazou, two women who have been extensively involved in the organization of art initiatives across the division. Ezgin and Toumazou, in a presentation in Nicosia that was part of the Bufferzone Art Project, organized by Apartment Project, Istanbul in March 2013, described the various bi-communal art projects that they have been involved in organizing, noting how contemporary art has been used since the opening of the borders in 2003 as a means to share everyday life events, contributing to bringing people together, and assisting peace-building through the development of inter-personal relationships.10

Efforts since the 1990s have been driven by friendships and mutual peace-seeking. The opening of several crossings since 2003 and growing interest in microhistories have been thrusting holes into the seemingly opaque fabric of history, opening spaces for togetherness and revealing commonalities. Ideological, personal, and creative commonalities between people across the Buffer Zone now echo the commonalities between Cypriots who for generations lived together, were educated together, and at times fought together.

The political history of Cyprus is often remembered by the unyielding rivalries of political leaders and failed talks, especially during the 1980s between Rauf Denktash and Glafkos Clerides. However, what is less known is the comradery between the two men, their acquaintance as schoolboys at the same school and mutual respect as peers as they trained as barristers of law together in England. The friendships born out of shared spaces are familiar to us personally. For example, the first time we met Cypriots across the divide prior to the opening of crossings was our freshman year at university in England. The importance of shared environments and the lasting impact on a people is significant, demonstrated on a small scale in personal accounts (including several between Clerides and Denktash) as well as on a larger scale in the organizational activities of civil society groups that have been working to create spaces of dialogue and activity by means of socially situated art.

In the Mapping section of this case study attention is placed on independent socially situated and critical art organizations and collectives and the activities they propose with a particular focus on work across and around the Buffer Zone. The organizations and initiatives that contributed to this mapping include: AA&U, European-Mediterranean Arts Association (EMAA), Free School, Hands on Famagusta Initiative, NeMe, Pikadilly, Re Aphrodite, Rooftop Theatre Group, Sidestreets Culture, Studio 21, Urban Guerillas, Visual Voices, and Xarkis. They propose a variety of methodologies and typologies of actions. These range from educational/learning methodologies, residency programs, exhibitions, research, public space actions, collective working, community led spaces, and many other types of socially situated activities. As organizations they focus, not only on issues that relate to inter-ethnic relations and conflict transformation, but also on universal issues of human rights, feminist platforms, LGBTQI, labor union action, and on building dialogue between Cypriots and second and third-generation migrants and other communities living in Cyprus. This is by no means an exhaustive mapping and there are many other organizations and initiatives that engage in socially situated art practices. However, these initiatives have been active in shaping artistic action and research that create bridges across the Buffer Zone and points of contact, exchange, and dialogue. Behind these organizations and civil society groups are people that shape art projects and wider community actions that have an impact on other people’s lives through their involvement in these actions (varying from small scale endeavors to large scale funded projects).

It is important to note that the work of these people and their initiatives most often happens below the surface, beyond what is visible, behind cameras, and between the lines. Such work might be termed silent activism. Here forms of mediating through the arts deploy practices of connecting and caring in order for exchange to take place and in so doing mark precedential acts that delineate our borders in malleable ways. Both of us, the editors of this case study, are involved in developing relationships across the Buffer Zone through artistic practices and in writing about such practices. Even though it is not a first to try to map and reflect on such practices,11 it is a first for two Cypriot art historians who live either side of the dividing line to bring together such an extended number of examples of socio-politically engaged art practices. To do it at a moment in time when threats of war, sanctions, and diplomatic discords between Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey regarding sea sovereignty and claims over the natural gas lying at the bottom of the Eastern Mediterranean waters dominate our news, this case study is perhaps an insistence to try and dream beyond the popularized image of strife and threat dominating our screens.

Every small step is a mark of activation and activism and when considered in relation to the art practices discussed here, they are seen as a process of activating, enabling, and resisting dominant hyper visible narratives of ethnic identity and belonging. The Buffer Zone itself is a site of simultaneous hyper visibility in the landscape (due to its imposing presence cutting across land and sea) and also of invisibility, as it restricts the contact between groups of people through the military controlled restrictions to movement (with six different armed forces surveying its land). The sustained efforts by artists and activists to overcome its restrictions cannot but create an interrelation between the ideas of art and activism, itself a burgeoning field of focus amidst the wider socially engaged/ critical art debates.12 The way that art relates to activism can be discerned both in the parallel work of artists as activists and in the work of artists working in the public space and with communities. The work of Twenty Three and Hüseyin Özinal is juxtaposed in the section Art, Activism, and Politics of Resistanceso as to draw out the common experiences of how artists create works about and with those who are unseen and unrepresented transforming hidden voices into a realm of visibility. These range from the privacy (intimacy) of a blank page, the public realm of social media, or the public space of city walls and streets.

Representations of hidden and unseen lives are traced in Hüseyin Özinal’s drawings, with battered and incomplete bodies coming into centre view. These solitary bodies stand unwilling and in resistance to forming ideal representations and are yet simultaneously faded and present in all their fragility. In parallel to these at once abstract and figurative drawings, the artist has developed an activist practice focusing on homophobia and associated inequalities in reference to personal experiences and observed historical accounts such as the life of Behic Gokay, a gay Turkish Cypriot, and one of the first conscientious objectors (refusal to enter into the compulsory military service for men that is the law in Cyprus) in the 1960s. Other issues the artist addresses include: child labour and drug abuse (especially prominent issues in 1970s and 1980s İstanbul coinciding with Hüseyin’s formative years as an art student); wider issues of abuse (particularly the rising number of violence against women and femicide killings); as well as physical deterioration and difficulties relating to ageing and elderly care.

Twenty Three also makes the hidden and unseen visible but rather via works made and presented in public space: street art that acts as a socio-political statement and involves communities. Whether he is working along and across the Buffer Zone, a refugee social housing estate, or in Chiapas in Mexico, Twenty Three’s work in public space and with diverse publics has a distinct critical note to the socio-political realities of contemporary life, in which universal imagery is combined with coloquial references to Cypriot identity. Such open spaces are used by Twenty Three as temporary portals of engagement and dialogue that potentially amplify views that may often remain minotarian among larger populations.

As Stavros Karayiannis points out in a paper discussing a queer-reimagining of the Buffer Zone, “the Dead Zone” is seen “as internal as much as it is external, as subdued by memory but, at the same time, directing remembering, a passive repository an active catalyst.”13 For Karayiannis a “‘queer re-imagining’ implies an exploration of the potential of a topos to inspire emotions, thoughts, possibilities that reach beyond the dominant narratives, transverse, and go across essentialist national discourses.”14 Pointing to the importance of this reimagining as being not only subversive or deconstructive, he draws from the potential that the “queer” and queer theory could present us with so as to penetrate “deeply into the interstices of history and spatial dynamics”, making “silence audible”, rendering “essentialism awkward”, politically resisting and challenging the “regulatory practices of power” of our supposed no-man’s land.15 Through this prism the Buffer Zone can be understood as the space where we, those who aim to challenge and resist the regulatory practices of power , of the dominant ethno-national narratives reside: trying to reimagine lives in common. Through this process the Buffer Zone is being continually rethought in creative ways, cunningly redefined, and is increasingly considered among younger generations as a “third-space”, one that symbolizes hope, incites fascination and togetherness as well as a future that can be reshaped (as opposed to a silent monument of division and dead-ends that causes fright and despair). As we write we are once again not able to meet freely. But this space, this case study also functions as a “third space” and common ground for independent artistic practices that are socially situated and that hope to cultivate a fertile ground of further actions and dialogues that resist military divisions.

***

Esra Plumer-Bardak

Art historian, researcher and active member of non-profit art associations. Alongside teaching and writing, she engages with collaborative projects that have a social focus as mediator, consultant and/or mentor. Esra received her PhD in Art History at the University of Nottingham in 2012 and has also completed a PG-Dip in Arts Management and Cultural Policy from Queen’s University, Belfast. She is currently working as one of the art consultants for the European-Mediterranean Arts Association’s EU Funded Project ‘Art for All’ (2018-2021) and holds the position of Assistant Professor at the Arkin University of Creative Arts and Design, Cyprus.

Evanthia Tselika

[PhD] is an assistant professor specializing in art history and theory at the University of Nicosia. Her research concentrates on social practices and histories of art, with a particular focus on the commons and politics, as well as visual cultural histories. She collaborates with art centres and museums locally and internationally, and is involved in curating European level funded programs, such as the Interreg Balkan Med project Phygital (2017-2020). Her articles are published in journals such as Visual Studies and Public Art Dialogue and commissioned by organizations such as Peace Research Institute Oslo. http://evanthiatselika.com.

1 We are informed in this reading by literature relating to participatory, socially engaged and situated artistic practices such Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London and New York: Verso Books, 2012); Grant Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley/London: University of California Press, 2004) and The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Duke University Press: USA, 2001); Suzanne Lacy ed, Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art (Seattle: Bay Press, 1995); Loraine Leeson, Art: Process: Change: Inside a Socially Situated Practice (Abington: Routledge, 2017) and Gregory Sholette, Delirium and Resistance Activist Art and the Crisis of Capitalism (London: Pluto Press, 2015).

2 Anna Solder Grichting, “From a deep wound to a beautiful scar: The Cyprus Greenlinescapes Laboratory” in Grichting Solder et al, Stitching the Buffer Zone (Nicosia: Bookworm Publications, 2012)

3 Please see Yiannis Papadakis et al eds., Divided Cyprus: Modernity, History and an Island in Conflict (Bloomington/Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2006) and Yael Navaro-Yashin, The Make-Believe Space: Affective Geography in a Postwar Polity, Duke University Press: USA, 2012)

4 See: Grichting, (2012); Ozgul Ezgin & Argyro Toumazou, “Buffer Zone art presentation” in Buffer Zone Apartment Project 2013, http://bufferzonew.appspot.com/static/about.html˃ [accessed July 2020]; Haris Pellapaisiotis, “The Art of the Buffer Zone” in Wells et al, Photography and Cyprus: Time, Place and Identity (London: I.B. Tauris, 2014) and Evanthia Tselika. “Conflict Transformation Art: Cultivating coexistence through the use of socially engaged artistic practices”, 2019. PRIO Cyprus Centre Report, 4. Nicosia: PRIO Cyprus Centre, 2019. [accessed July, 2020] https://www.prio.org/utility/DownloadFile.ashx?id=1942&type=publicationfile

5 Grichting, 2012.

6 The centre is a shared inter-communal space that aims to develop cooperation and dialogue amongst all Cypriot ethnic communities. It hosts a number of NGOs, seminar and lecture rooms and a cafe. It is funded by multiple organisations including the European Economic Area and Norway Grants, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It is a site where many actions related to peace-building are held and it is an indicative space of how the Buffer Zone could be transformed into a third space, a site of cooperation (http://www.home4cooperation.info/).

7 Nicosia Master Plan Final Report. UNDP, UNCHS [HABITAT]: Nicosia, Cyprus, 1984.

8 A historic meeting took place in Berlin between Cypriots in 1989: https://movementsarchive.org/doku.php?id=el:magazines:entostonteixon:no_41:berlin

9 Tselika, 2019.

10 Ezgin & Toumazou, 2013.

11 See Pelapaissiotis, 2014 and Tselika 2019.

12 See Nina Felshin, But is it Art? The spirit of art as activism (Seattle: Bay Press, 2015) and Boris Groys, “On Art Activism”, e-flux Journal #56 – June 2014. http://worker01.e-flux.com/pdf/article_8984545.pdf [accessed July, 2020]

13 Stavros Karayiannis, “Zone of Passions: A Queer Re-Imagining of Cyprus’s No Man’s Land”, in Synthesis 10, 2017

pp. 63–81, p.67 https://ejournals.epublishing.

ekt.gr/index.php/synthesis/article/view/16244 [accessed July 2020]

14 Ibid, 66.

15 Ibid.