Clandestine Becomings <Between Approximations and Deviations>

Anita Sobar in collaboration with Kenia Maia

A Point of Inflection

Silence can be experienced as forgetting. How is it that silence assimilates forgetting? At the point in which being silent produces forgetfulness. This essay affirms the collaborative dimension of art as a means of transforming secrecy into collective memory. Kenia Maia is a teacher, psychologist, activist, and friend. We met through our participation in the Coletivo Filhos e Netos [Collective of Children and Grandchildren of former political prisoners and the missing during Brazil’s military dictatorship 1964 – 1985] – an autonomous, social, and suprapartisan movement focused on the fight for human rights and tracking down the traces of violence committed by the civil-military dictatorship.1 Through my encounter with Kenia the artistic work presented here opens up to another dimension to explore how the transference of emotional, physical, and social pain suffered by family members as a result of state violence and torture is transmitted to new generations, beyond just being a learned behavior.

The transgenerational effect of violence echoes in hidden ways, it is difficult to produce meaning, amidst fragmented and buried memories, affected by silence and forgetting. Here, we see the efficiency of oppression in dictatorial states. It is in the construction of this writing, also perceived as a multitude, that we learn from the presence of the other, challenging limitations and creating new narratives. Writing was a dance of holding each other, recovering memories, feeling together, and encountering ourselves.

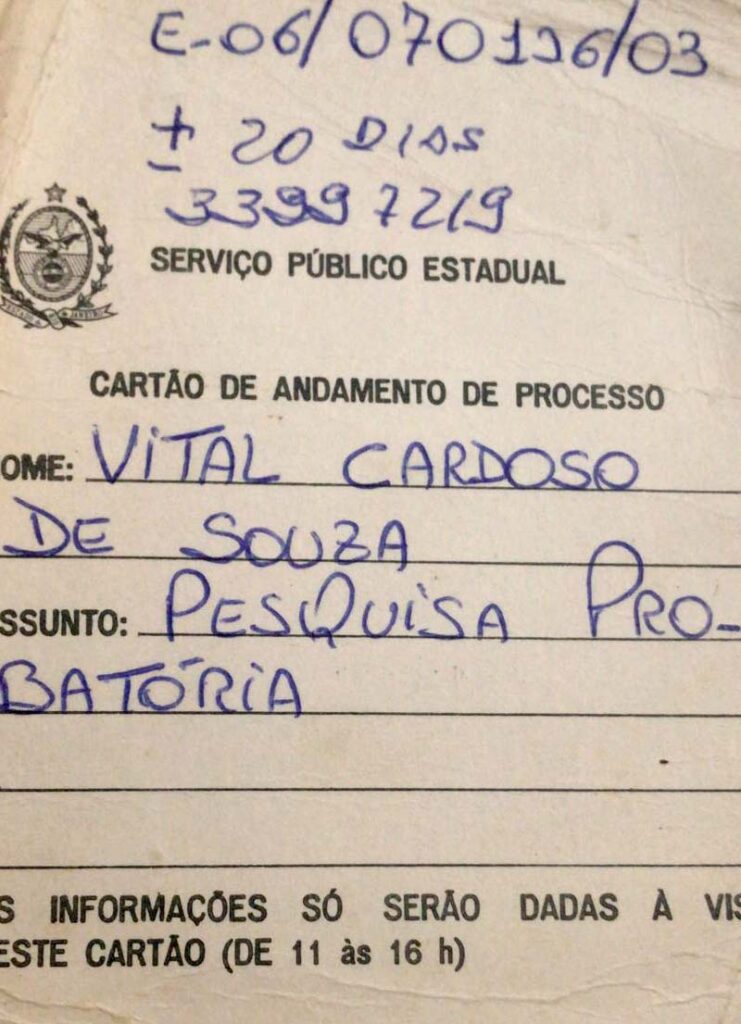

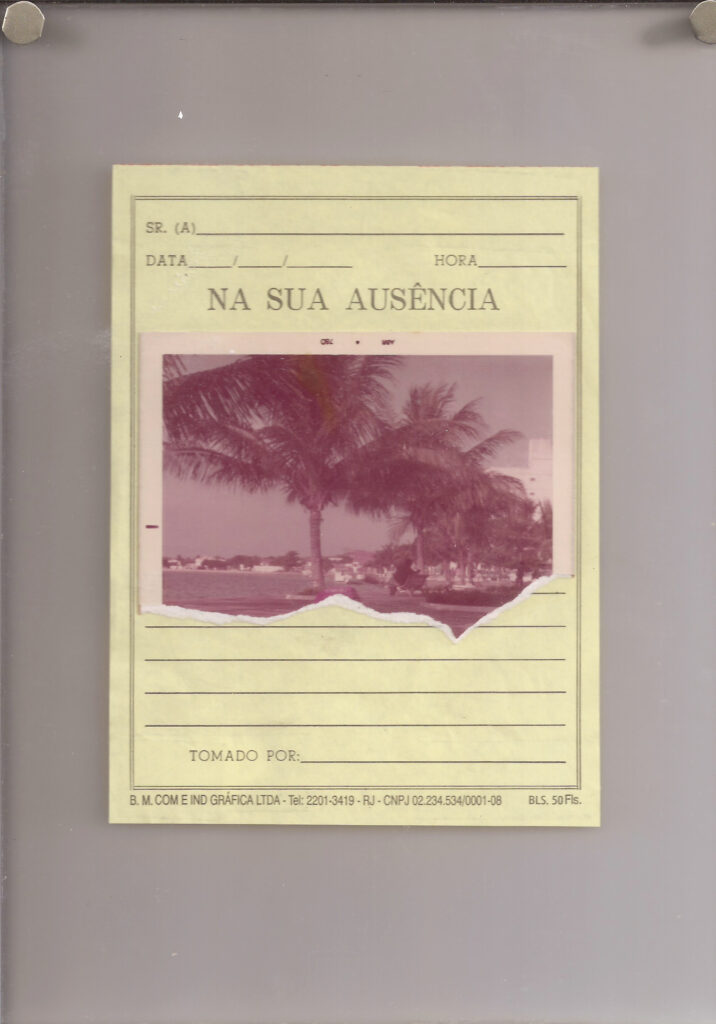

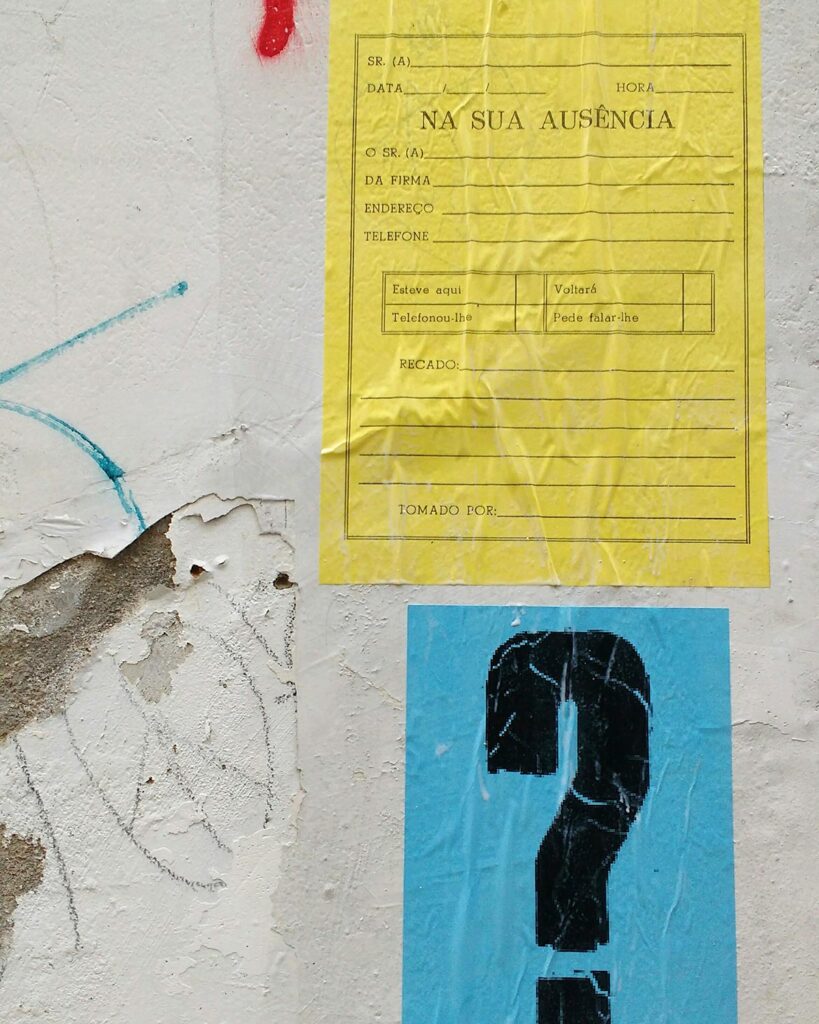

Just before we finish one of our conversations, via whatsapp, Kenia sends the image of a card / official form that she found as she was organizing things following a move. The card, after years, carried the weight of the memory of one of her incessant searches into the history of the period in which her father was imprisoned. It was to provide access to possible documentation in the National Archives of Rio de Janeiro. The search for evidence did not take place at the time. Keeping the ‘access card’ rather became evidence of the impediment to accessing the documents of her father’s political arrest.

What is the relationship between silence and forgetfulness? Silence produces forgetfulness through processes of letting go, disappearing, making things irrelevant. The state has this expertise of producing mechanisms of oblivion, mainly through bureaucracy. By bureaucratizing the pain of violence, the state dilutes the urgency of the facts in a continuous and slow flow of papers, forms, and protocols, amidst departments and declarations, numbers and endless folders. This state apparatus silences us.

As a means of countering this silence and forgetting, this text was written in collaboration, a coming together of both daughters. When, in the text, the reference to “father” appears, the story of Anita’s father is being told, but all the children [of the Collective] are included in it, including Kenia’s father.

Between Approximations and Deviations

This body of work <entre aproximações e desvios> [between approximations and deviations] consists of a series of reflections based on aesthetic-political actions, carried out in the urban centers and peripheries of the cities of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Belo Horizonte. In a broad sense, it is about creating and organizing devices to produce and share forms of collective engagement, of being together or separated, outside or inside, at the front or in middle. Ways to reconfigure a certain space or a certain time to trigger sensitive sharing experiences. Addressing questions of place, housing, and construction that also concern issues of work and the distribution of social space, this writing is a cartography of the clandestine artist. It explores the process of the encounter of social, emotional, and transgenerational space with state violence and divergent and disobedient forms of art production.

Clandestinity is understood as “the boldness of being other and oneself,”2, a losing of oneself to exist again in the collective. When at a crossroads, the clandestine being chooses to say goodbye to him or herself, leaving behind their affections, objects, memories, ones that they may never find again. This loss is part of the choice for life, not only theirs, but also of the possibility of the common good. The clandestine experience is singular – a world of nomadism, little baggage, and few objects. Nothing that weighs and can’t be left behind. The opposite of accumulations, clandestinity dedicates itself to the world without borders, where nationality is lost. It might be just an experience but it nevertheless marks profound modes of being and acting, producing permanence.

Between investigation and performance, the clandestine artist produces actions in the urgent present, with their own logic, producing subjectivities that only clandestine experience enables, creating multiple marks. Ones conceived in a web of relationships with the “other”, understood in the broadest sense, from the other people with whom the clandestine artist lives to the environment where daily life intervenes, the changes, choices, preferences, and memories produced in this context. By connecting these paths, testimony becomes a fundamental part of the composition of this practice, traveling between places of memory and the archive, seeking to put into motion the exercise of telling something, and creating diverse dynamics between image and writing. This movement returns to a present past, communicates with a social and family memory, and includes, as part of a cartography of the self, the wandering experience of the artist in dissent. Here, artistic making is crisscrossed by the transgenerational effects of state violence, by collectivity, acts of resistance, and vectors of transient and transitional forces. A story still missing in many respects may be told through art/intervention and clandestine modes of activist subjectivity.

This work has as its starting point an excavation process. Digging. Remembering. Only the most careful exploration of layers rewards excavation, not only an original find, but also the excavating itself, the very crisscrossing of layers making an inventory of findings. Memory is deployed as a form of knowledge – the systematization of its forms of registration, storage, and control. The act of digging proposes an action of opening up a cavity on a given surface, creating holes and openings for discoveries. The cracks of upended surfaces prompt a questioning of the symbolic limits of the public and private. In this context, dynamics develop, generating tensions between the present time and the resonances of memory, crossing different historical temporalities and narratives through various agencies.

Erraticness and dispersion are part of the scene to be narrated. Certain places, events, bring about the feeling of anguish and euphoria, occurring when there is a commitment to risk.

Starting Point – Clandestine Becomings

Every beginning is a regression, an action of returning, a recovery. A revisiting of the silences of a past that, in turn, never cease to reconfigure themselves. Every beginning is a tense gesture of incommensurate meaning. As a counterpoint, it is a question of elaborating a gesture of recovery, with attention and care, the strange resurgences, lacunae, and hesitancies, of the past in the present, when they appear as a flash in a moment of danger – clandestine artistic practice works similarly.

Art is political, when it cannot be explained in terms of institutional effectiveness or the structures of ideological pragmatism. It goes beyond conventions, establishes links between forms of collective action and the possibility of transforming power relations. It is closer to everyday inventions – the art of doing things – than to the organizational structures and precedents of old politics in the strict sense. Associated with social issues (often inspired by them) including the collaborative participation of groups and publics both in the conceptualization and production of the work. It is a way of penetrating the sociopolitical organization of life.

Rancière notes the double bind in which the artist is implicated at once needing to deal with the responsibility of the politics of art and political art: “Art does not produce knowledge or representations for politics. It produces fictions or dissensus, agencies of relationships of heterogeneous regimes of the sensible.”3 According to Rancière, the worker must also “get out of his/her own mind”4 in order to be able to see his/her position sensibly.

In the aesthetic regime of the arts, according to the author, art and politics are merged by the dynamics of dissension, shuffling, and reordering the “distribution of the sensible”.5 In turn, for Agamben,6 art and politics are inherently political as human activities affected by the opening up to potential.

For example, Nove de Tarnac, a French group of nine alleged anarchist saboteurs: Mathieu Burnel, Julien Coupat, Bertrand Deveaux, Manon Glibert, Gabrielle Hallez, Elsa Hauck, Yildune Lévy, Benjamin Rosoux and Aria Thomas. In 2008 the group was accused of “criminal association with terrorist activity”, on the grounds that they allegedly participated in the sabotage of power lines on France’s national railways. On April 12, 2018, after a lengthy and complex court case, the group was acquitted of the most serious charges against them, including sabotage and conspiracy, with some members being convicted of minor charges. This is one among many examples in which political and clandestine artistic actions are still pursued and criminalized by the state. In this case the “terrorism” that this art presents is the threat to the hegemonic ways that the state propagates and officializes. Clandestine, terrorist, and disruptive art terrorizes official discourse, so it is criminalized and imprisoned.

Artistic intervention makes use of means as simple as it is precarious. Wheat pasted posters, drawings, photographs, letters, tickets, documents and other disused objects impregnated with memories. Bringing these objects to the streets together with publics creates an urban laboratory, involving diverse audiences in the realization of an art project. This movement is the detonator of critical processes that can produce public spheres of discourse.

Hanna Arendt proposes that the term “public” derives from two closely related phenomena: what becomes public can be seen and heard by everyone thus constituting reality and that the greatest forces of intimate life – from the thoughts of the mind to the delight of the senses – live a kind of dark existence, until they are deprivatized and deindividualized made suitable for public appearance.7 The most common of these transformations occurs in the artistic transposition of individual experiences.

Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the fold refers to this co-existential aspect of the inside and outside, as well as a configuration between the flows and forms that interconnect particular historical planes, belonging to the order of the event. Such considerations encourage us to observe certain deviations that escape fixed contours, such as the concept of the nomadic.8 Nomadic thought considers the event as something that provokes surprise and produces disaccommodation, that is, it constitutes the very mobility of thought, as a protest.

According to Deleuze and Guattari territories are composed of smooth and striated vectors in which a co-engendered relationship occurs as a translation of the smooth into striated modes.9 The smooth is an immanent dimension of modes of subjectivity production in space and the striation of these modes form, reveal, and configure these vectors. Like the maps of the great navigations in the modern and colonialist period, the striation of the immenseness of the Atlantic was what made it possible to manage this smooth space, reaching new continents to explore and master them. Striation is a mode of mastery, but it is also constitutive of spaces, as it is of smoothness.

The authors also present the weaving dynamics of the territories of capitalism, where the lines that make up these fabrics are limited and defined in pre-established dimensions of width and length. In weaving processuality there is always the production of an inside out. Indissociable from justice, the hidden, and the occult, inside outs shelter clandestinity, warming its surfaces and protecting it. Striation is the verticalization of history that organizes the smoothness of subjectivations and hides the clandestine ways of being and acting, also produced by the violent machinations of the state-weaving machine.

The state also produces clandestineness in two aspects: when it pursues and criminalizes divergent modes of expression that denounce its hard, fascist, and unequal front, and when it hides its “devices” of death and torture. The state also uses the clandestine to hide its violence in narratives of official history, as a mode of not revealing.

Beyond the End Point: Transgenerational Effects

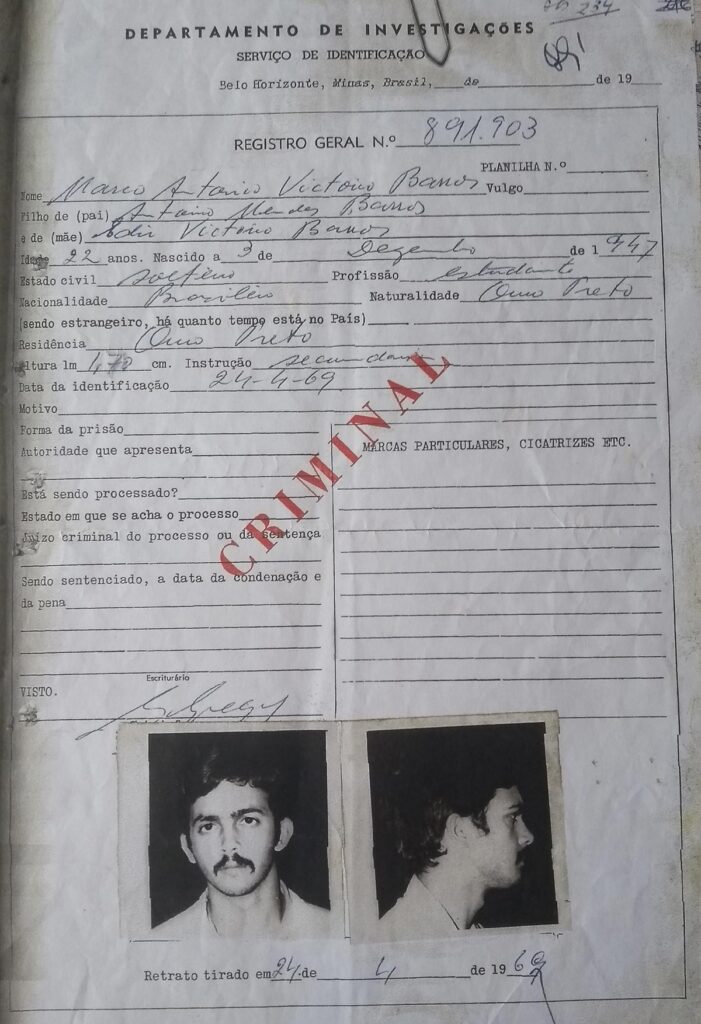

Being the daughter of a former political prisoner held during the Brazilian military civil dictatorship (1964-1985) has also meant bearing the weight of his four-year history of incarceration in the now defunct Linhares prison in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais. The first time the activist of the group Corrente Revolucionária [Revolutionary Current] stepped into the Minis Gerais prison was at the end of 1969, when he was only twenty years old. In 1973, when he left, his face no longer resembled the young man whose codename was “Play”. He was now a bearded man and marked by the period of seclusion. Often, as a daughter, the only way to connect with that experience is to activate an excavator process of a traumatic and painful experience, veiled and silent, only possible to unveil through the plane of the sensible. Rarely narrated memories, lived histories, and experiences are perceived via the nonverbal and are told as art.

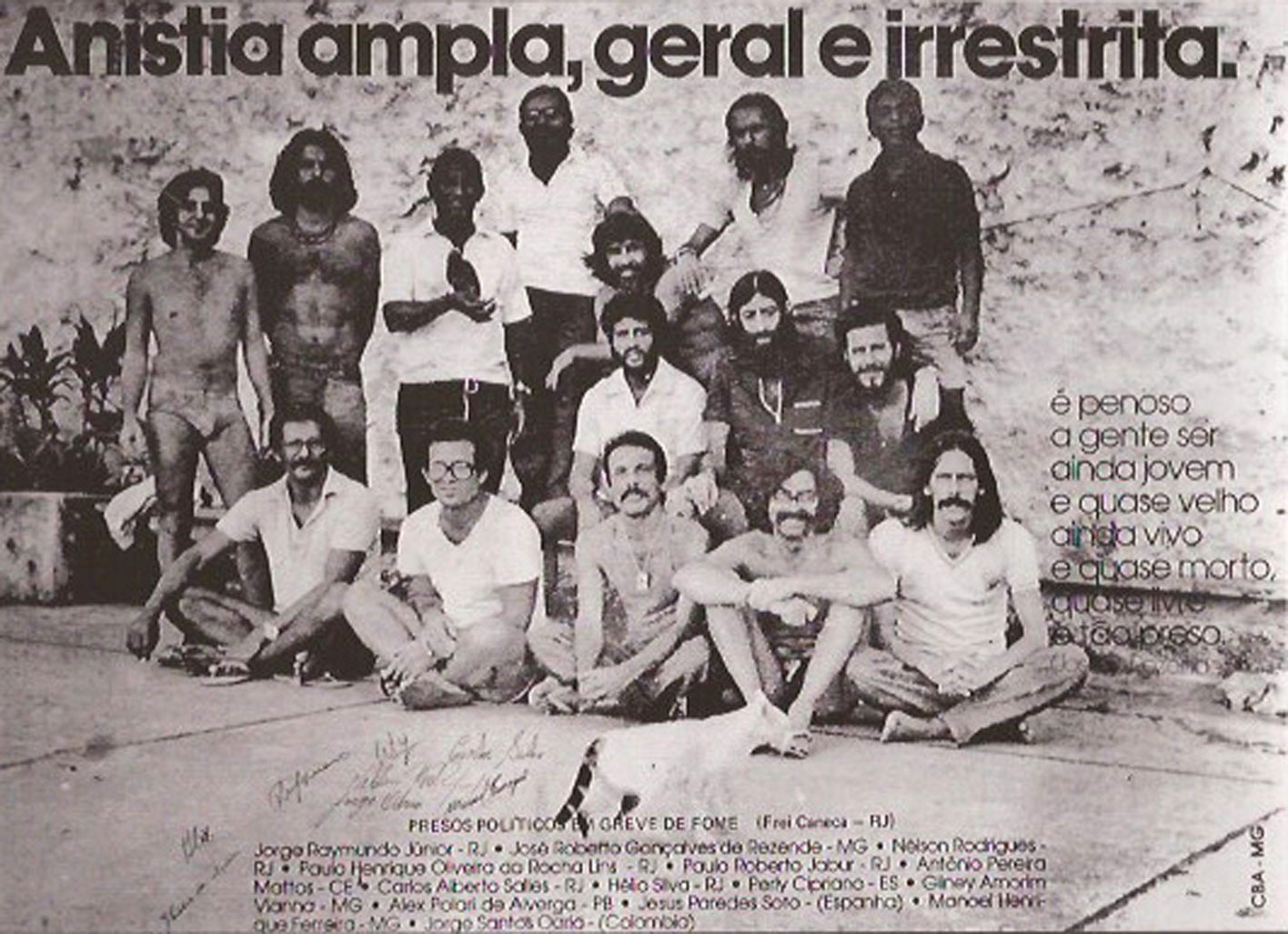

Throughout my childhood a poster hung in my parents house that produced a series of affects and affections, as it seemed to unite a significant set of gestures. The poster image was of a photograph that was used to publicize the campaign for Brazilian political amnesty in 1979. In the photo, political prisoners posed in a courtyard on their third hunger strike occurring in the Frei Caneca Political Prison of the Milton Dias Moreira prison complex in Rio de Janeiro. They were held in a renovated and isolated ground-floor prison with an entrance and internal courtyard intended exclusively for political prisoners. The strike took place between July and August 1979, during the government of General João Batista Figueiredo, in response to the Amnesty bill sent to The National Congress by the President that excluded political prisoners who had been accused of violent crimes. The intention was to organize a national hunger strike for broad, general, and unrestricted amnesty.

In the photograph there is no concern with the outside, but rather an inner freedom, there is more a sense of a zone of indetermination between activity and passivity, between thought and not thought. The image is not supposed to think, it is rather supposed to be the object of thought. The thought, not of those who see, but of those who objectify, turning the image into a campaign poster message. This indetermination stems from deterritorialization, from a life in prison created through forming strange deviations. The indetermination in the image displaces the victim status that the poster propagates. The question is not whether or not it is necessary to disclose the horrors suffered by violence, but in the construction of the victim as an object of the visible. The poster is political when it subverts the dominant logic and shows the hidden, veiled discourse, the effect-life, the reason to be free and so imprisoned.

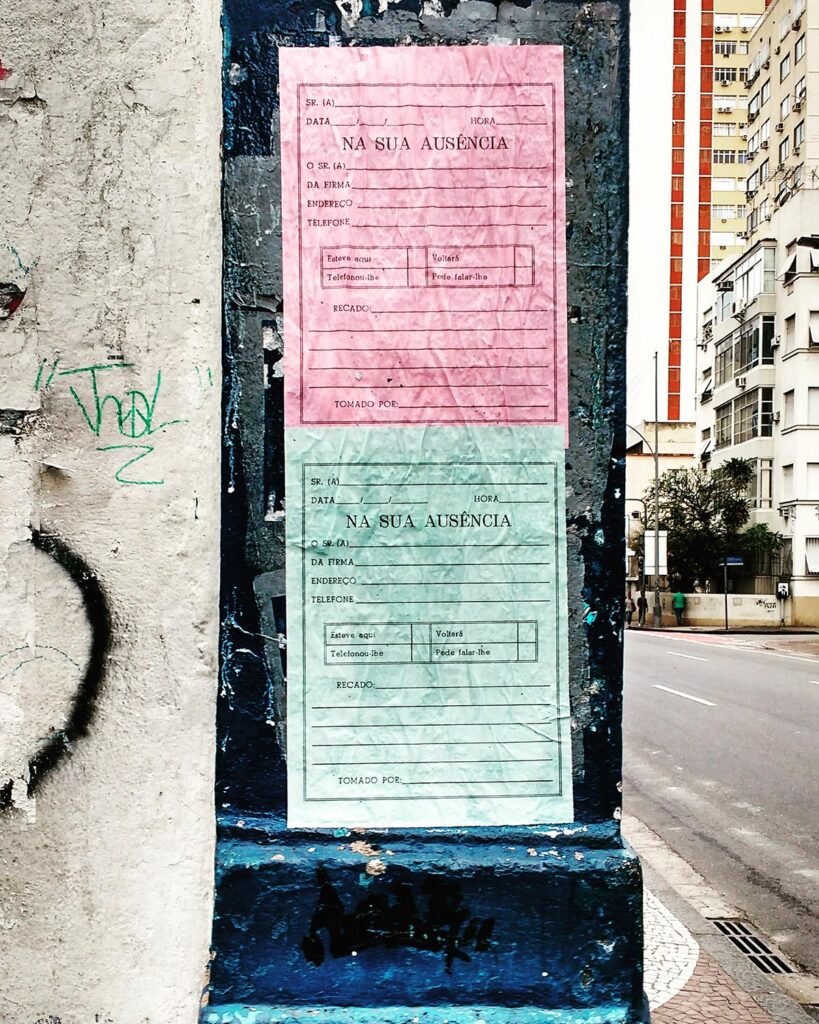

The power of that image was the catalyst for the series Na sua ausência [In Your Absence] consisting of two approaches to montage (technique and presentation): one using wheat pasted posters and the other small collages. While they both use official forms as a point of departure, they are standalone pieces, even though coexisting. The series is part of research that draws on the formerly analogue graphic/administrative materials of an office, a public servant desk, and bureaucratic practices such as: accounts, receipts, forms, memos, records etc. These information devices become authoritarian institutional rubble – among them my father’s criminal record and the ‘access card’ used by Keina. Both address the dynamics of information and its deployment in the development of logics and values aimed at improving institutional, governmental, and political actions. Managed in archival spaces, they formulate discourses and projects of subjectivation via documental actions.

The photo, its potency, and these documents can be perceived as a rhizomatic network of affects and memories. They connect with each other stimulated by the message, “Na sua ausência” [In your absence]. Such everyday images are impregnated with the sensible. “Na sua ausência,” in your silence, amidst silencing and daily routines, crisscrossed by resistance to state authoritarianism, fascism, torture, social inequalities, and genocide, memory was constructed. This non-individualized memory, although familial, manifests itself in the collages and posters, drawing on the forms, bureaucracy, and procedures of the state apparatus, as a way of denunciating the bureaucratization of death and the absence of many political activists. Memory becomes present via actions that are the effects of the transmission of trauma that in turn become artistic interventions, and in that process can be transformed into clandestine activity, free and protected, powerful and provocative. The children and grandchildren of political prisoners and the disappeared did not escape the denunciation of the violence of the Brazilian state, and the artistic proposition that expresses the bureaucratization of life and the concealment of death and brings out the power of this transgenerationality.

Much has been said about the transgenerational effects of state and other historical and ongoing forms of violence, such as racism, as modes of suffering, and indeed they are.10 Art offers the transformative potential to express this transgenerational memory as artwork. This transgressive action is affirmed as an exhibitor of trauma, of collective pain that inhabits a family history. Art does not cure trauma, because there is no disease to be cured. It exposes the unspoken. It translates a hidden language, an experience omitted from society by official history.

Archives respond to power relations that govern a culture. They reflect the awareness that all assimilated matter is a document of the machine of discourses, visibilities, and affects of the context from which they arise. This may be straightforward but as such it opens itself up to a political act, where engaging with the transfer of this context already configures a reading and points to interests that result in ethical definitions.11

This is true to the archive: its lacunar nature. For an archeology of the image, we have to identify that we have to make do with the effects and gestures of a world that only delivers us residue. We find ourselves, therefore, faced with an immense and rhizomatic archive of heterogeneous images difficult to master, to organize, and to understand, precisely because its labyrinth is made up of intervals.

Times redone and contradictorily undone, artistic experimentation seeks to think about contemporary life and its symbolic division between public and private, lending weight to the discussion artist / archivist, maker of other worlds, calling for a stubborn protest against the standard and the classifiable. Walter Benjamin, when referring to the ambiguity of attitudes towards the past, analyzes the passion of the collector.12 Not only was he a theorist of collecting, as was the central motivation that he called “bibliomania,” he also saw in the act of collecting marks of the drive of children. For the child things are not yet goods, they are not evaluated according to their usefulness, thus allowing the transfiguration of the object with disinterested pleasure.

The collector renews the world via a small intervention in objects, a kind of rebirth, as Hannah Arendt puts it.13 Benjamin could understand the collector’s passion as an attitude similar to that of the revolutionary. As a revolutionary, the collector dreams of his/her path not only to a remote or past world, but also, at the same time to a better world where surely people are devoid of what they need in the ordinary world, but where things are freed from the humiliating work of utility.

These ideas help to think about the universe of contemporary artistic practices. The world opens up and is renewed drawing on gestures of remembering and archival recollection as keys to organize what goes on in the civilizatory promise. This occurred in the totalitarian and fascist regimes of the 20th century. Megalomaniacal archival projects that aimed to create a submissive society and reduce its individuals to obedience. As a response, today, more and more, in the era of “archive fever”14, there is a way of thinking and acting emerging that distrusts the archive and, as a stubborn protest returns our gaze to our history.

Power relations and tactics of subjectivity take place both on macro-political and micropolitical scales. The violence of coups threatens “the ‘right’ to life, to the body, to health, to the satisfaction of needs”.15

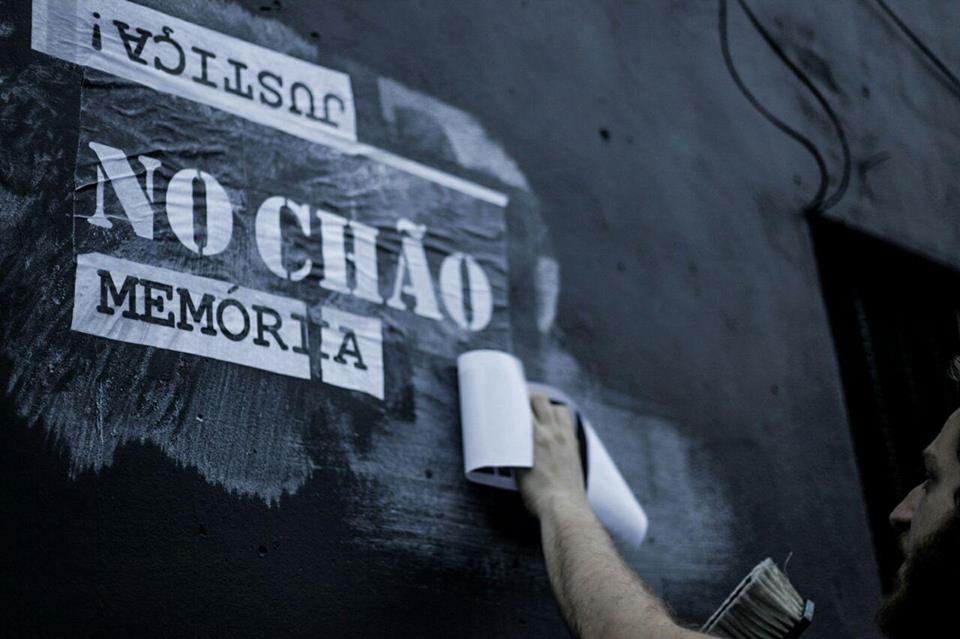

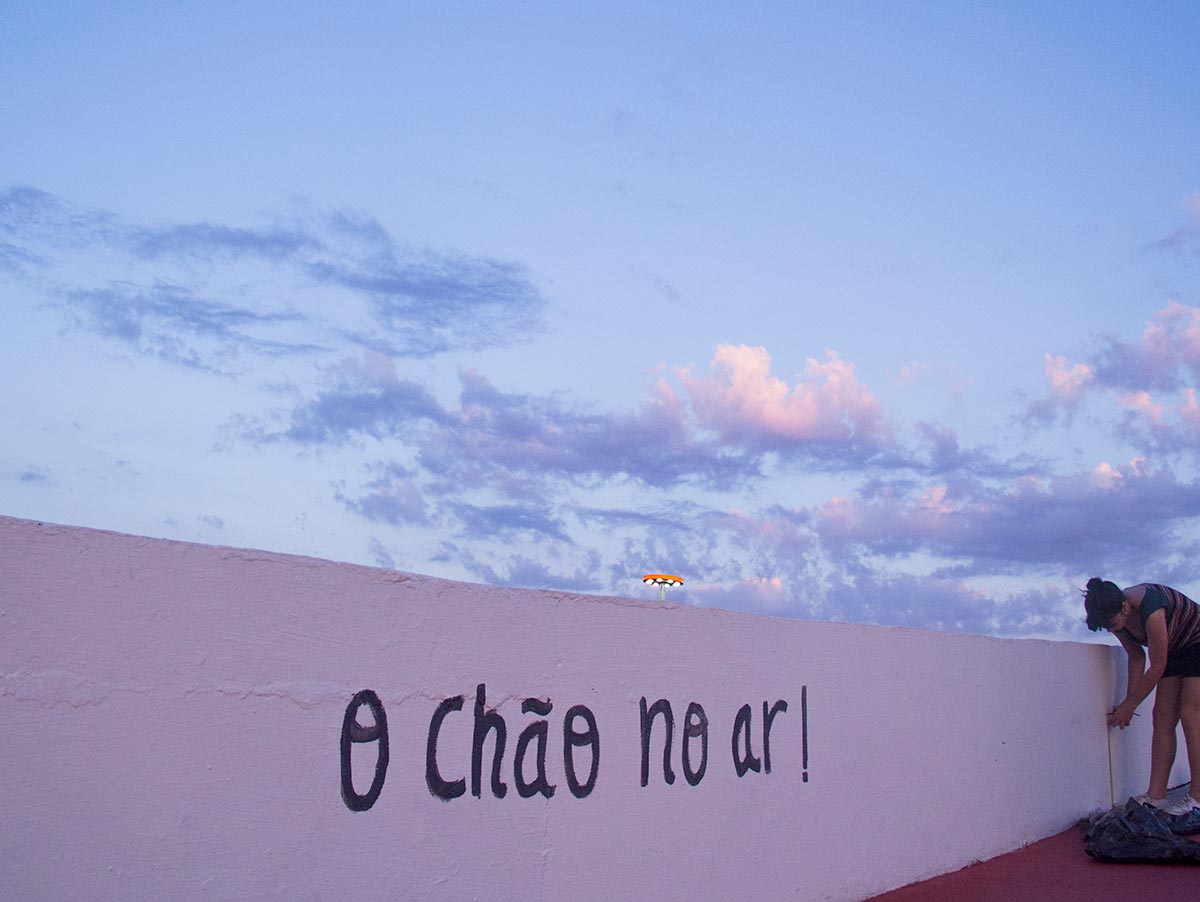

Another artistic action that is part of the cartography being mapped here was the installation of wheat pasted posters and the writing of phrases on the walls of the city of Rio de Janeiro and at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Niterói (MAC). The poem “O chão no ar” [The Ground in the Air] was cut into sentences and written on the walls of the city and at MAC. The following phrases were impregnated: “How to produce counterconducts?”, “Pulse everywhere”, “The world is immense, but within us it is deep as the sea”, “Find yourself a utopia”, “The ground needs art” and “Art needs ground”. These actions occurred in 2017 and comprise an experience of the relationship between the spaces of power and territories of resistance.

Resistance necessarily takes place where there is power. Resistance founds power relations as much as it is power. It is the possibility of creating spaces of struggle and brokering possibilities of transformation according to Foucault.16 From this perspective, the counter-conduct is a form of resistance. Counter-conduct corresponds to a type of governmentality aimed at defining new modalities of struggle. It is important to think what form counterconduct assumes in the current crisis. The word “conduct” refers to two modalities of action: the activity of conduct itself and also the way a person conducts him or herself and the way they let themselves be led – one passive and the other active.

The wheat pasted posters and cut up phrases intervene in the specificities of the museum as a public and state space and the street as a space of the hidden, anonymous, and provocative. Modes of counter-conduct were applied in both contexts together with forms of rewriting ways of doing/being/acting through the sentences. In the occupation of the museum, even if by unusual means, the artist came out of the underground to transgress the walls of the state and the private. In the street the artist appropriates the city and makes the people emerge. Without identifying herself, without authorship, the artist undoes herself in forces, lines, and vectors. In the artist’s clandestine future, art becomes an instrument of counterconduct, hidden in activism and movement, transforming what has been silenced.

Back to the Beginning: Now that I’ve found it, I can look for it

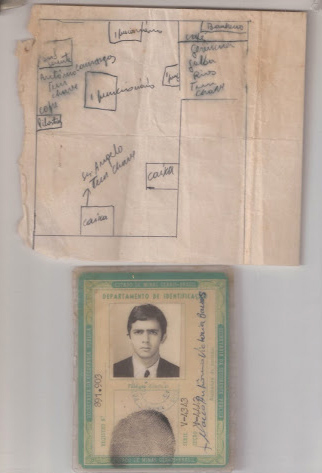

On June 15th, 2017, my father’s belongings that had been seized at the time of his arrest in 1969 arrived by mail. They included tickets, identity cards, and a little calendar that he had been carrying in his pants’ pocket. Among other frivolities, he had the drawing of a map of a bank – a sketch of a planned guerrilla attack. These belongings had been held for almost forty years. A relationship between absence and presence evokes a strange sensation. While taking into account all the difficulties that weigh on the experience of the rememoration of a traumatic event, it is nevertheless an opportunity to investigate: what are the permanences of the violence of the dictatorship? What are the strategies to combat such permanence? When dealing with the construction of a memory against forgetfulness, witnessing as a form of resistance carries the paradox of the unspeakable. This reinforces the value of witnessing as a manifestation between the sayable and unsayable.

The moment these objects arrive as testimonies of a time taken away by the state, they return the reminiscences of a life. Time disarrayed, evidence of an old event. Reminiscences encounter other memories and testimonies as the artist creates a collective experience with other children and grandchildren of political prisoners in Rio de Janeiro.

The collective Filhos e Netos por Memória, Verdade e Justiça [Children and Grandchildren for Memory, Truth, and Justice] was formed at the end of 2013, within the framework of the Clinical Testimony Project of the Ministry of Justice, and had as its founding event at the Public Hearing “Transgenerational Effects of State Violence”, held at Universidade Estadual Rio de Janeiro in December 2014, as part of the Rio de Janeiro State Truth Commission, the Clinical Testimony Project and the Amnesty Commission. The collective promotes, collaborates, and supports campaigns, actions, demonstrations, and projects linked to the theme of memory, truth, justice, and reparation – particularly in cases of state violence past and present.

In the process a network of the relatives of the politically persecuted was created and revealed the strong influence of participation in the collective as key for my art practice, which brings me back to the beginning. This understanding is related to the process of constructing the self and constructing the self as an artist. Every beginning is a returning.

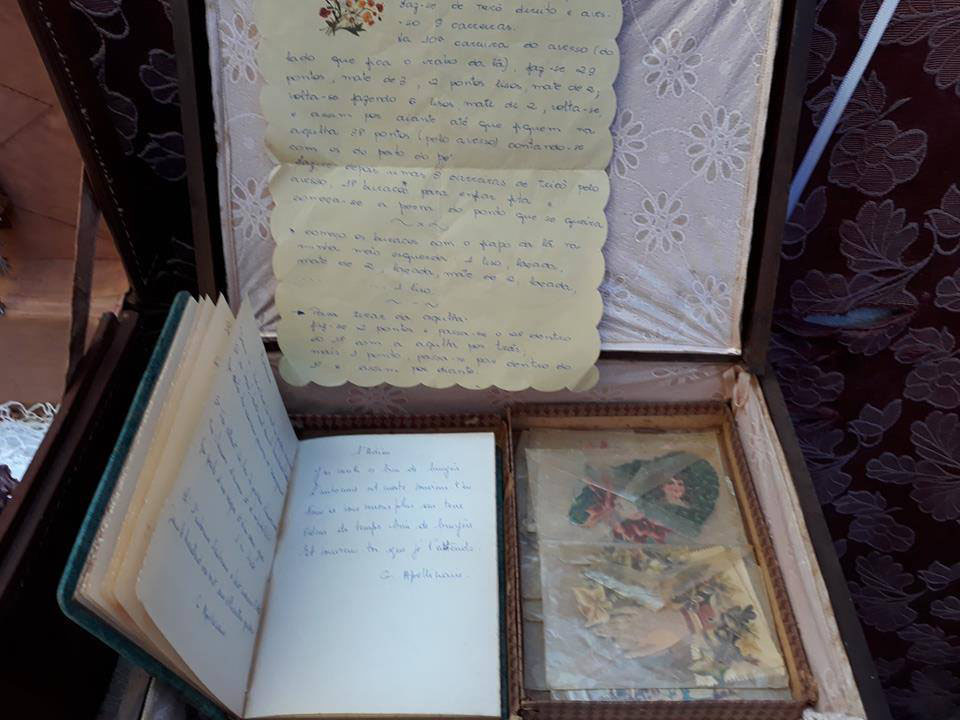

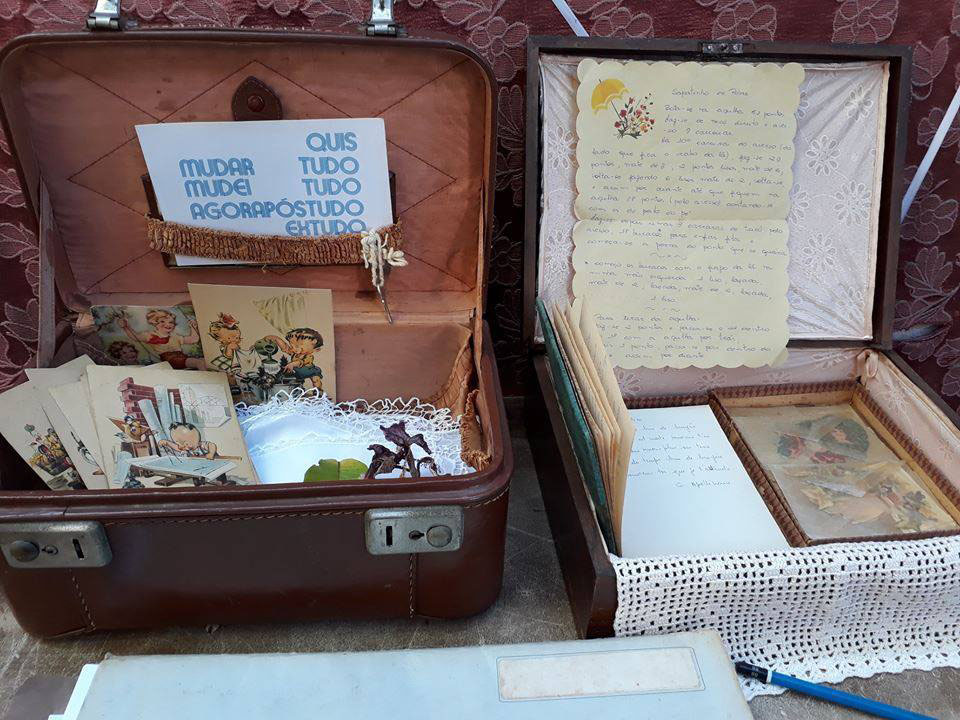

The issues become fundamental between the “construction of self” and the “construction of self as an activist/artist”. The meetings of the collective generated the production of ethical-aesthetic-political agencies. In November 2017, we held the art exhibition and testimonies as poetic practice project called Destempos [Out of Time] at the Cia de Mystérios e Novidades [Company of Mysteries and Novelties – a theatrical performance group] in Gamboa, Rio de Janeiro. Via collective and creative enunciations, the proposal was to enable the testimony of those affected by state violence and the effect it had had on their bodies. Inviting the experimentation of other languages, not to illustrate or represent horror and pain, but to activate the legacy of this force of (re)existing and to make art as a possibility of converting violence and trauma into the power of acting, thinking, and creating. To this end, it was possible to make public the private archives for a true reinvention of the relationship between the public and the private, breaking barriers of silence and potentializing the struggle for truth, memory, and justice.

The protest is in the surprise. Beyond the intense work of each group member’s presentation, it was the act of opening up the most intimate archives and revealing their revolutionary poetics, until then hidden and repressed, where the surprise of this collective encounter with these aspects of subjectivity assumed the forcefulness of a protest. By making use of objects, poems, drawings, among many other stories and charms, the collective took the form of a social sculpture.

In a historical context of non-public recognition of crimes of serious violation of rights and bodies, committed during the Brazilian dictatorship, the damages produced by state terrorism have repercussions in the present, and continue in the preceding generations producing transgenerational effects. The end of dictatorial regimes in Latin America did not mean an end to the damage caused by state terror. This terror continues to act within the social fabric, especially in contexts marked by policies of forgetfulness, silencing, and impunity. They are the central axes of post-dictatorship state policies in Latin America – retraumatizing mechanisms par excellence. The meetings of the collective of children and grandchildren and the possibilities of expression and support that the collective allows, as occurred in the exhibition/event Destempos, are fundamental for the deconstruction of the loneliness of those who live with the consequences of state violence. The artist’s clandestine future is collective and takes shape in creative and expansive processes. To think of art as an eternal beginning is to give agency to its origins making sayable the unsayable.

***

Anita Sobar

Anita Sobar is an artist, researcher, and educator. She graduated with a degree in fine arts from Universidade Federal de Rio de Janerio (EBA – UFRJ) with a specialization in graphic design from the British School of Creative Arts in São Paulo. She holds a masters degree in Contemporary Studies of Arts from Universidade Federal Fluminense (PPGCA – UFF).

Kenia Maia

Kenia Soares Maia is a professor of psychology at Federal University of Tocantins (UFT). She has a masters in clinical psychology from Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) and a doctorate in clinical psychology PUC – Pontifical Catholic University – Rio de Janeiro.

1 The collective Filhos e Netos for Memory, Truth and Justice is a suprapartisan autonomous social movement of human rights. They produce public events, research and projects connected to themes of memory, truth and justice and reparation of state violence past and present.

2 M. A. A. C., Arantes, A clandestinidade, uma opção de resistência, Revista Princípios, Edição 31, NOV/DEZ/JAN, 1993-1994, pp. 65-69.

3 RANCIÈRE, Jacques Rancière, O espectador emancipado (São Paulo, S P:Editora Martins fontes, 2014) p 59.

4 Ibid. p. 61.

5 Ibid. p. 50.

6 Giorgio Agamben.,Profanações (São Paulo: Boitempo, 2007).

7 Hannah Arendt, A condição humana, tradução Roberto Raposo, pref. Celso Lafer, 10ª Ed. (Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2007).

8 Gilles Deleuze e Felix Guattari, Mil Platôs: Capitalismo e Esquizofrenia vol. 5 (São Paulo: Ed. 34 Coleção Trans, 1997/2012).

9 Ibid.

10 P. E. C., Perez et al . Violencia de Estado y trasmisión entre las generaciones, Política & Sociedad(Madr.) 54(1) 2017: 209-228.

11 Suely Rolnik, O Furor do Arquivo, 2012.

12 Walter Benjamin, Obras Escolhidas vol I: Magia e técnica, arte e política (São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1985).

13 A condição humana, op.cit.

14 Jacques Derrida, Mal de arquivo: uma impressão freudiana (Rio de Janeiro: Relume Dumará, 2001).

15 Michel Foucault, História da sexualidae I. La volonté de savoir. Paris: Gallimard, 1976.p. 190 -191.

16 Michel Foucault, A ordem do discurso. São Paulo: Edições Loyola, 2009.